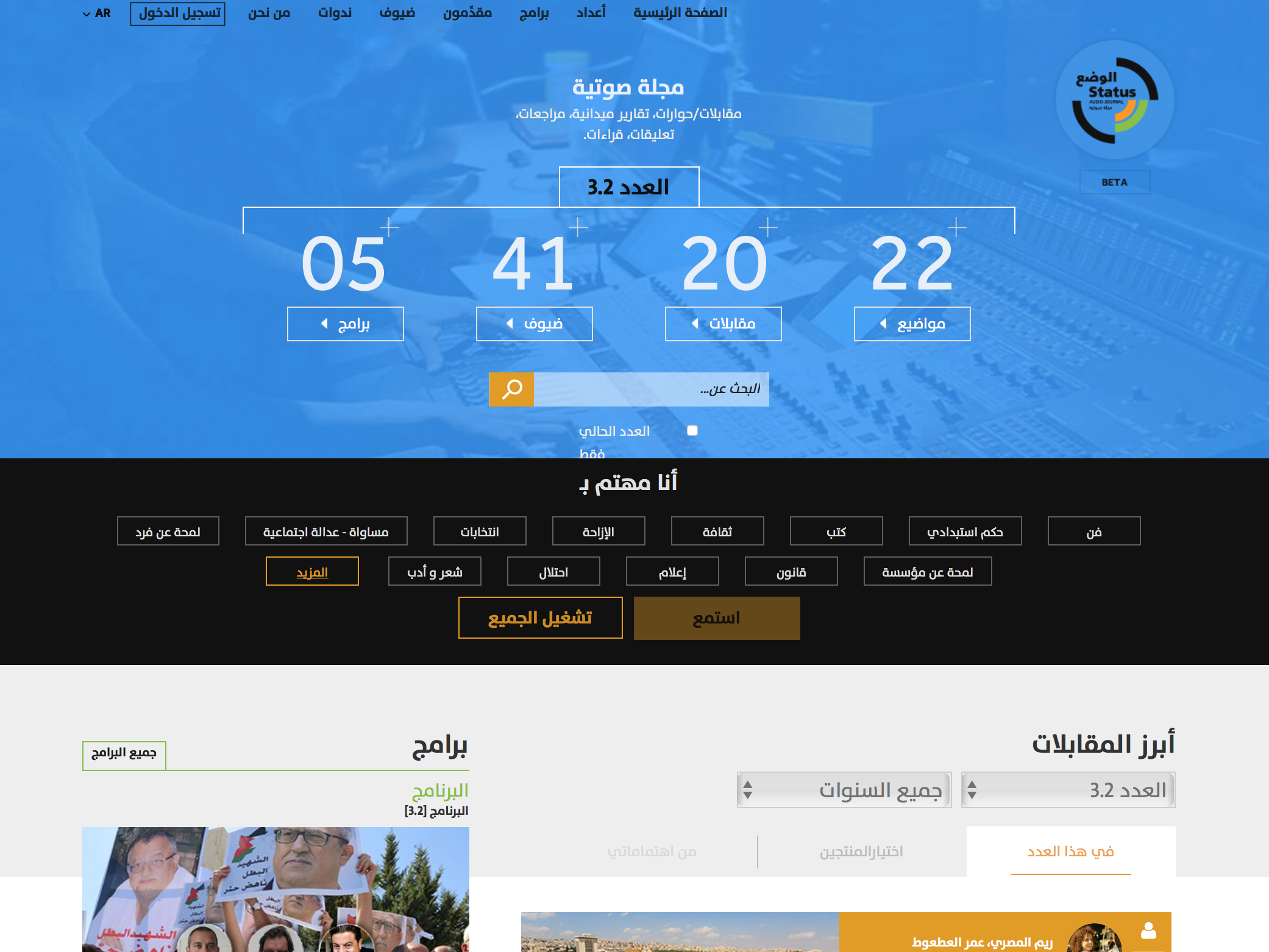

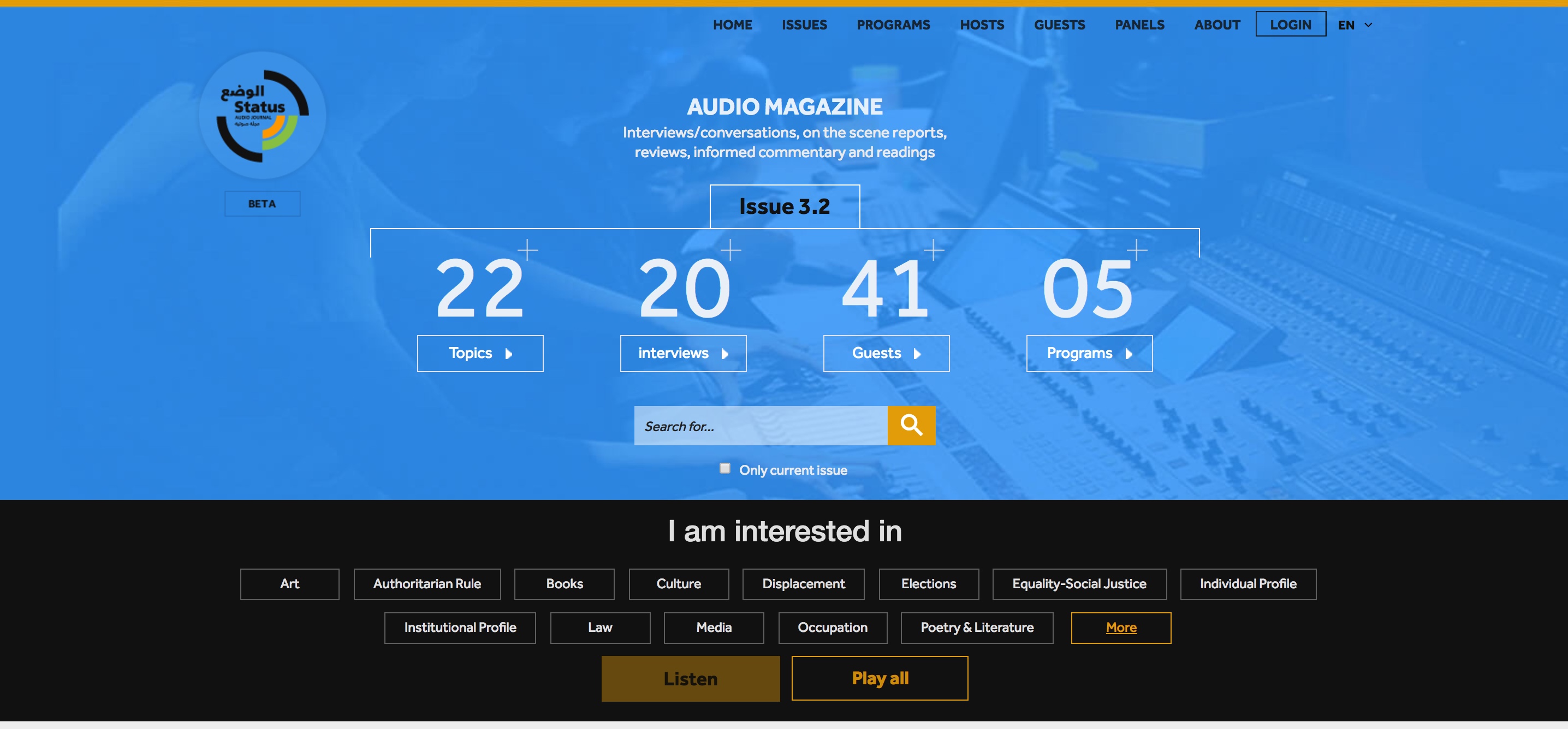

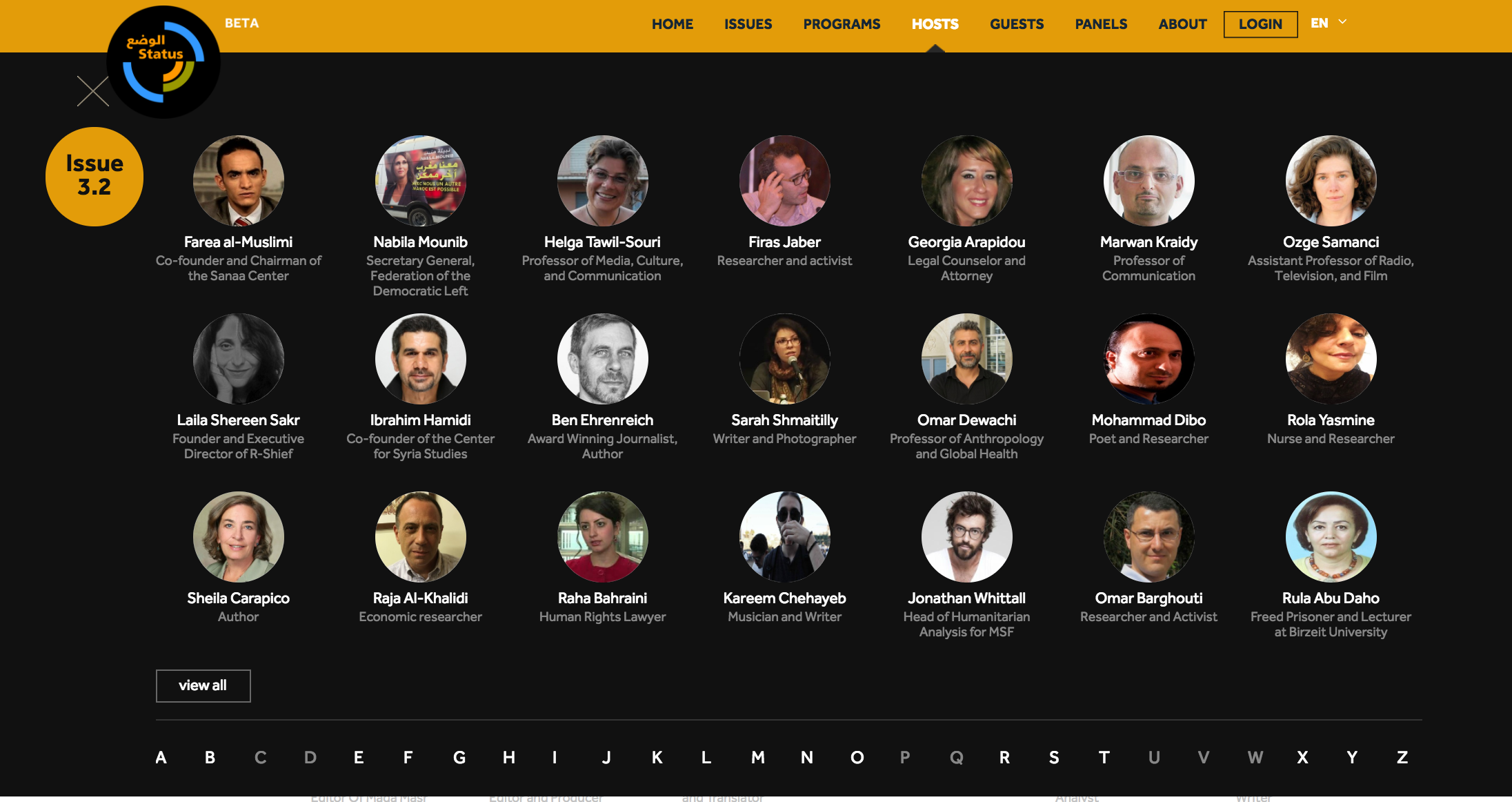

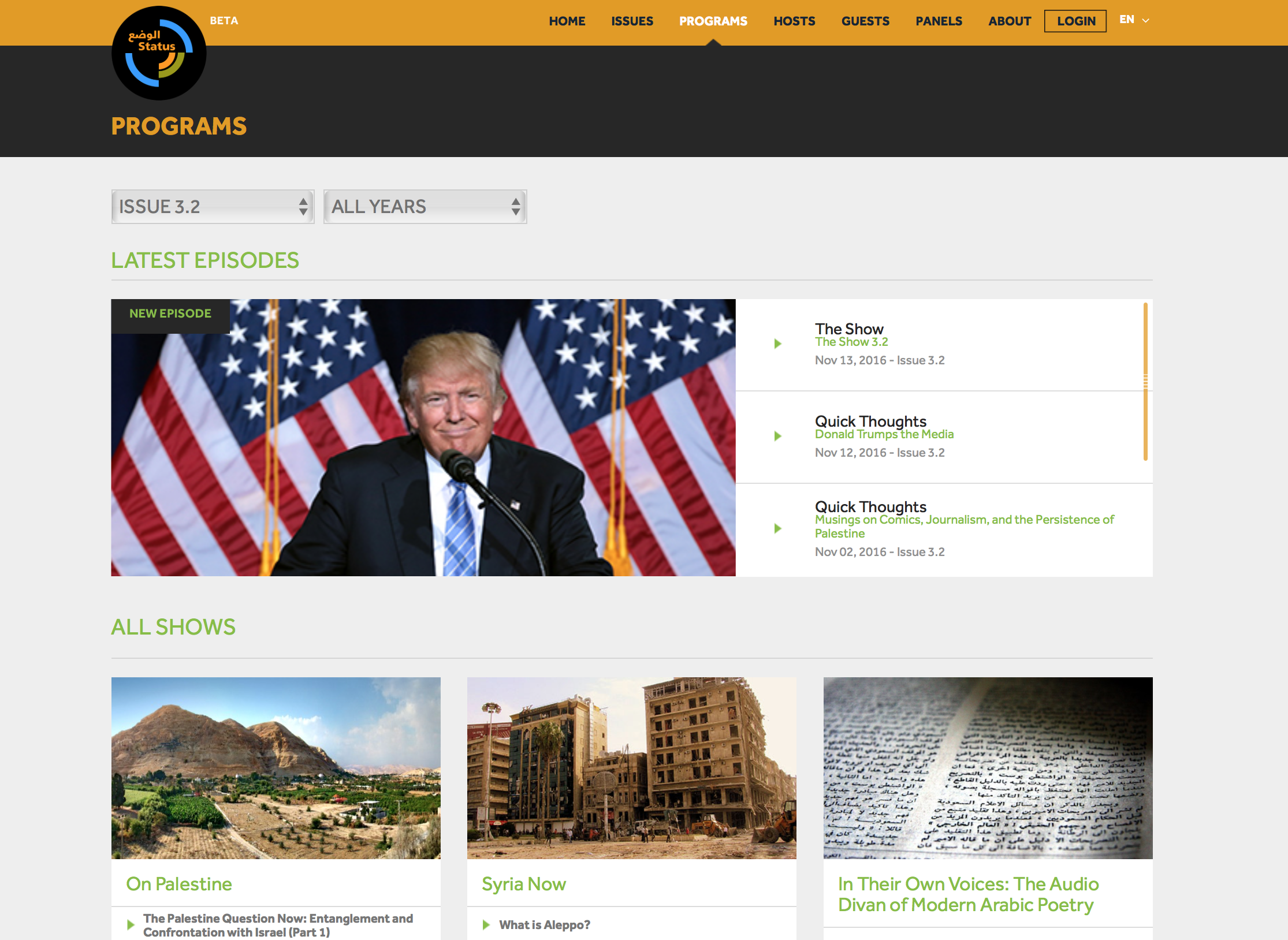

This holiday season, the Arab Studies Institute (ASI) is pleased to announce the official launch of its most ambitious project to date! Meet Status الوضغ Audio Magazine!! A bilingual Arabic and English audio site with interviews and programs about the region unrivaled in their depth and scope. This first “official” issue on our spanking new interactive and fully customizable website includes twenty interviews with forty-one guests on twenty-two topics!

But first for the backstory! For a little over a year, we have been toiling away producing the beta version of Status—a quiet avalanche of media production that goes against the grain in every conceivable way! Some of you may have come across or listened to our incredible interviews with some of the most compelling artists, musicians, activists, and academics in and on the region. These are all archived by issue and searchable by topic, theme, country, and other categories for your easy perusal on the Status website.

In the tradition of Jadaliyya, Quilting Point, The Forum on Arab and Muslim Affairs (FAMA),Tadween Publishing, the Knowledge Production Project (KPP) and many other programs of ASI, Status الوضع is a turning point in the way the Middle East and North Africa are being mediated, as well as a sophisticated challenge to the mainstreamed oversimplification, myopia, and dehistoricization of a region in turmoil. Status aims to do things differently by offering a unique model of online audio production that is decidedly analytical and markedly connected to the life experiences of communities in the Middle East and North Africa. Creative production and in-depth discussions about these locales have not been forged in such an amalgamated way before—particularly that which combines scholarly inquiry with local activism, the arts, and culture.

A Fully Integrated Bilingual English/Arabic Website! ("مش مزح و لا لعب عيال")

With this new platform, you will have access to a fully integrated Arabic language site and content, featuring all aspects of the website. No longer is Arabic an add-on: Status/الوضع is now "بالعربي!"

Click below and see for yourself. Or here: http://www.statushour.com/ar/home

The Interviews

Unlike mainstream media—whose political economic structures or formats limit their local contacts and communications with publics to sound-bites—at Status we are intent on shepherding an anthropological turn that places the interview at the center of knowledge production on a region so often spoken of or for but rarely listened to. Longer form, candid, personal, reflective, and reflexive discussions about issues that affect people’s lives can, in fact, be done in a manner that introduces complexity rather than simplification. While this may seem anachronistic in an age where our consumption of information is becoming more abridged, choppy, and swift, we are convinced that there is a growing place for those who want to learn more, not “just enough.” It is on this premise that we reach out to those whose lives are touched by conditions in their milieus, are themselves affecting their locales, or are chief advocates for the plight of publics in their environs, to help us understand and inquire further. These interviews on Status, unlike those you listen to or watch on mainstream platforms, are not meant to conclude, summarize, or confirm, but rather to expand, expose, and enquire. While technically these interviews come to an end, the conversations themselves continue. The vast array of interviews on Status is truly a landmark feat (sure we are biased, but if you browse around the website you’ll see for yourself why we are so thrilled!).

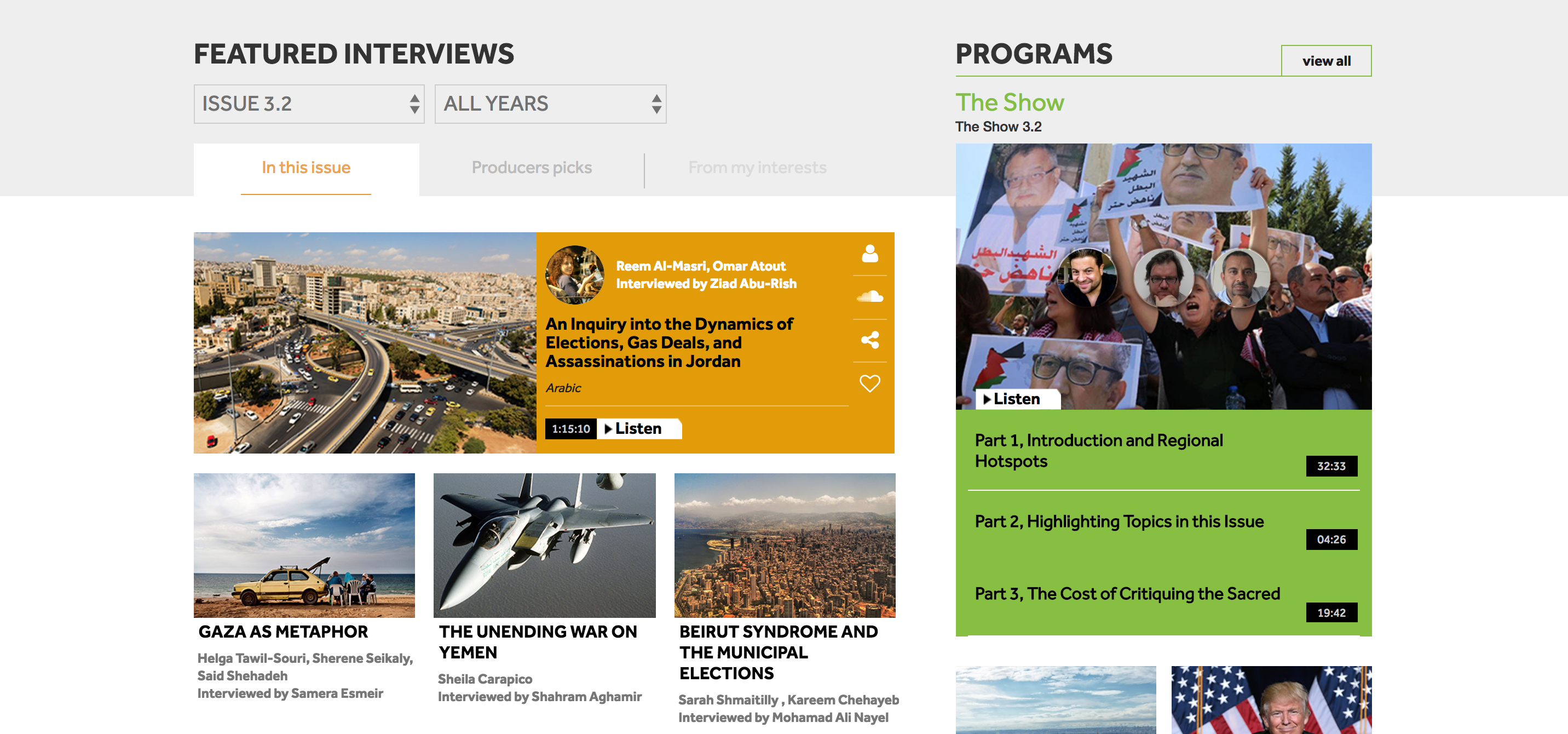

Here is an outline of what we have in store for you in this Launch Issue 3.2:

In the flagship program for Status, Bassam Haddad, Adel Iskandar, and Sinan Antoon discuss (in Arabic) the interviews in this issue and grapple with the pressing struggles facing the region. In this issue’s installment, they tackle regional hotspots and the hefty cost of critiquing the sacred.

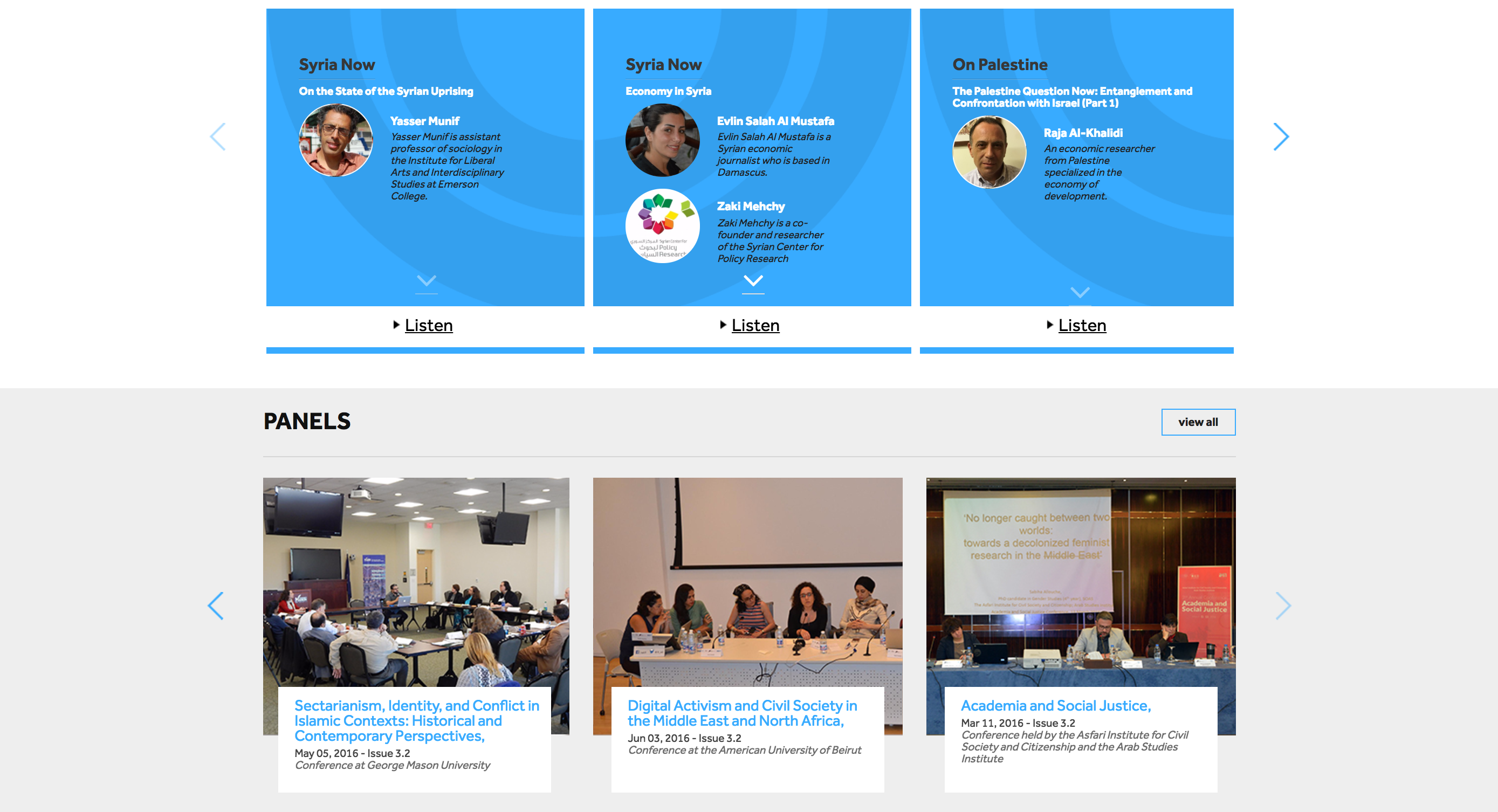

Syria Now

With the Syrian war at a turning point and the desperate need for reasoned contextual, historicized, and localized analysis at its greatest, as we have for the past year, we continue to bring to the fore passionate and critical voices on Syria. In this issue of Status, Ibrahim Hamidi of Al-Hayat talks about the tragedy in Aleppo and, in doing so, paints a bleak picture of a city not by simplifying the dynamics, but by explaining the complexities of life there today. Yasser Munif, who discusses the state of the country’s uprising given the recent developments, as well a discussion with Evlin Salah Al Mustafa, Zaki Mehchy, and Ahmad Haj Hamdo about the economic impact of the Syrian conflict and economic journalism in response to it.

Mouin Rabbani talks about the complicated Syrian quagmire at the United Nations and the political jockeying that has been the case in the Security Council over the past four years. Mohammad Dibo, the editor-in-chief of SyriaUntold, speaks to Status about his publication’s new project “Cities in Revolution,” which investigates the history of the Syrian uprising in six different cities. Kheder Khaddour is our guest in an important conversation about the critical role that tribalism, an often-underappreciated societal component, plays in the Syrian uprising. In each issue of Status, there will be a dedicated show entitled “Syria Now” that hopes to tackle the increasingly tragic conflict in the country with complexity and sensitivity.

Perennial Palestine

As mainstream and alternative media both succumb to pressures to focus on hotspots at the expense of the perennial struggle of the Palestinian people, Status places Palestine at the center of the regional struggle for freedom. We have a dedicated program in every issue called “On Palestine” which intends to complicate and introduce nuance to discussions about Palestine. In this issue alone we present spectacular interviews on Palestine-related matters. These include a discussion with Firas Jaber about the legal, social, and activist dimensions of the historically significant national campaign for social security in Palestine. Ben Ehrenreich talks about his new book “The Way to the Spring: Life and Death in Palestine,” in which he tackles Palestine in the US media, life under occupation, and the ceaseless struggle against this occupation. Also in this issue is an interview with Omar Barghouti, a co-founder of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement (BDS), on the movement’s background, focus, and trajectory in the coming period. With a large proportion of the Palestinian population having been incarcerated at one point in their lives in Israeli prisons, little focus is given to the experiences of women detainees.

In this issue of Status, we speak to Rula Abo Daho who reflects on a personal account of detention from a Palestinian woman’s perspective. Tariq Dana joins us for an interview on the critical problems faced by civil society organizations in Palestine and offers an appraisal of their impact and contribution to liberal perspectives and knowledge production in Palestinian society in light of their struggle to obtain funding. Palestinian Human Rights Defenders Raji Sourani and Shawan Jabarin talk to Status about the Palestinian dossier for the International Criminal Court (ICC) and their motivations to continue to push the court on legal violations committed against Palestinians, despite the political difficulties that affect the delivery of justice. We also speak to economic researcher Raja Al-Khalidi about daily life for Palestinians and the “Ramallah Bubble” as well as the differing economic circumstances in Jerusalem and the 1948 territories. Graphic novelist Joe Sacco, the author of Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza, talks about his artistic work and his focus on Palestine therein.

Doubling on Diversity

While we have highlighted above the Syrian and Palestinian content, these are by no means the limits of our programming. Instead, we are doubling down on diversifying our content from across the region in a way that is unlike other platforms. From an interview with a Lebanese tattoo artist Taha Sammour about the restoration of calligraphy in the art of Arabic tattooing to a regular Quick Thoughts segment with Laila Shereen Sakr about what is trending in the social media in the region (e.g., Saudis on Twitter, the war on Yemen, and Trump’s election in this issue), the topics and themes covered in each issue are a testament to the diversea and contoured local perspectives through which we believe the region must be reimagined.

With Yemen on the periphery of mainstream conversations about the region, we are keen on placing the limelight on the country with as many interviews as possible per issue. In this installment of Status, we interview Sheila Carapico on the unending war on Yemen, where she discusses the conditions in the country as well as Saudi Arabia’s complicated endgame in this protracted war. Another interview with Farea al-Muslimi discusses the meaning of moving the Central Bank of Yemen from Sanaa to Aden, the continuous war there, and the effects of “accusations of neutrality” on to those facing an escalation of violence.

At a time when microscopic analyses of human rights conditions in the region are seen as a critique of raging authoritarianism and a response to counter-revolutionary resurgence, Iran remains a blind-spot. For this reason, Status’ interview with Raha Bahraini is an important one, as it places the country’s human rights violations against activist Iranians or dual nationals at the center of any understanding of national progress. In a conversation with Reem Al-Masri and Omar Atout, we discuss a variety of issues facing Jordan. From an inquiry into Jordanian parliamentary elections and gas deals with Israel to the assassination of Nahed Hattar and the place of the monarchy in the political system, the guests offer a complex look at the country beyond the smokescreen. Rola Yasmine also joins Status for an important discussion about the patriarchal biases of the medical system in Lebanon and how they pertain to women’s health generally, and refugee women’s health specifically.

Sarah Shmaitilly and Kareem Chehayeb are guests of Status in an interview about the municipal elections in Beirut, political deadlocks, and the bewilderment of civil society. Elsewhere in Morocco, electoral politics have become much more complicated. Status presents Nabila Mounib, the only woman head of party in the country. The Secretary General of the Federation of the Democratic Left, Mounib delivers here a rousing and unique speech in a small town not far from the contested Western Sahara.

Other interviews include one with a professor of communication, Ozge Samanci, who becomes a graphic novelist and produces “Dare to Disappoint,” a debut work that grapples with the joys and toils of growing up a woman in Turkey. Omar Dewachi, the co-director of Conflict Medicine at AUB, and Jonathan Whittall, of Médecins Sans Frontières, talk to Status about changes that are happening to the ecologies of war in the region from both academic and practitioner perspectives. In the special program “Quick Thoughts,” Adel Iskandar discusses the Trump phenomenon through the prism of a media, in which Trump capitalized on both the complicities and vulnerabilities of the private news media in the United States.

In each issue, we will be featuring interviews with authors and editors of compelling new research works, books, projects, or curated exhibitions. In this installment of Status, we speak to the editor and authors of the new book Gaza As Metaphor: Helga Tawil-Souri, Sherene Seikaly, and Said Shehadeh. Another book highlighted in this issue is The Naked Blogger of Cairo. The book’s author, Marwan Kraidy, discusses his motivations to write the book and the crux of his argument about the role of the body as a communicative object.

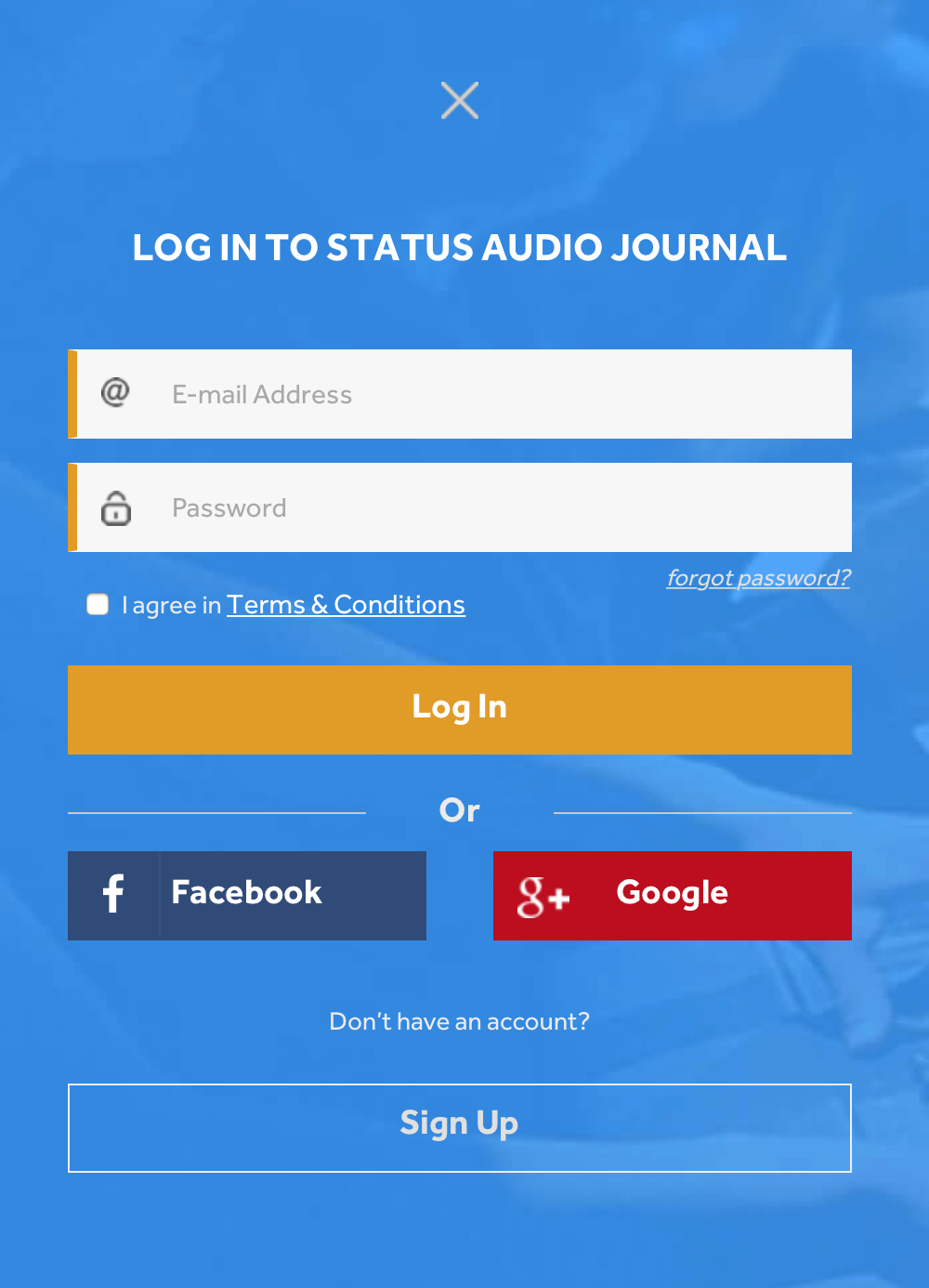

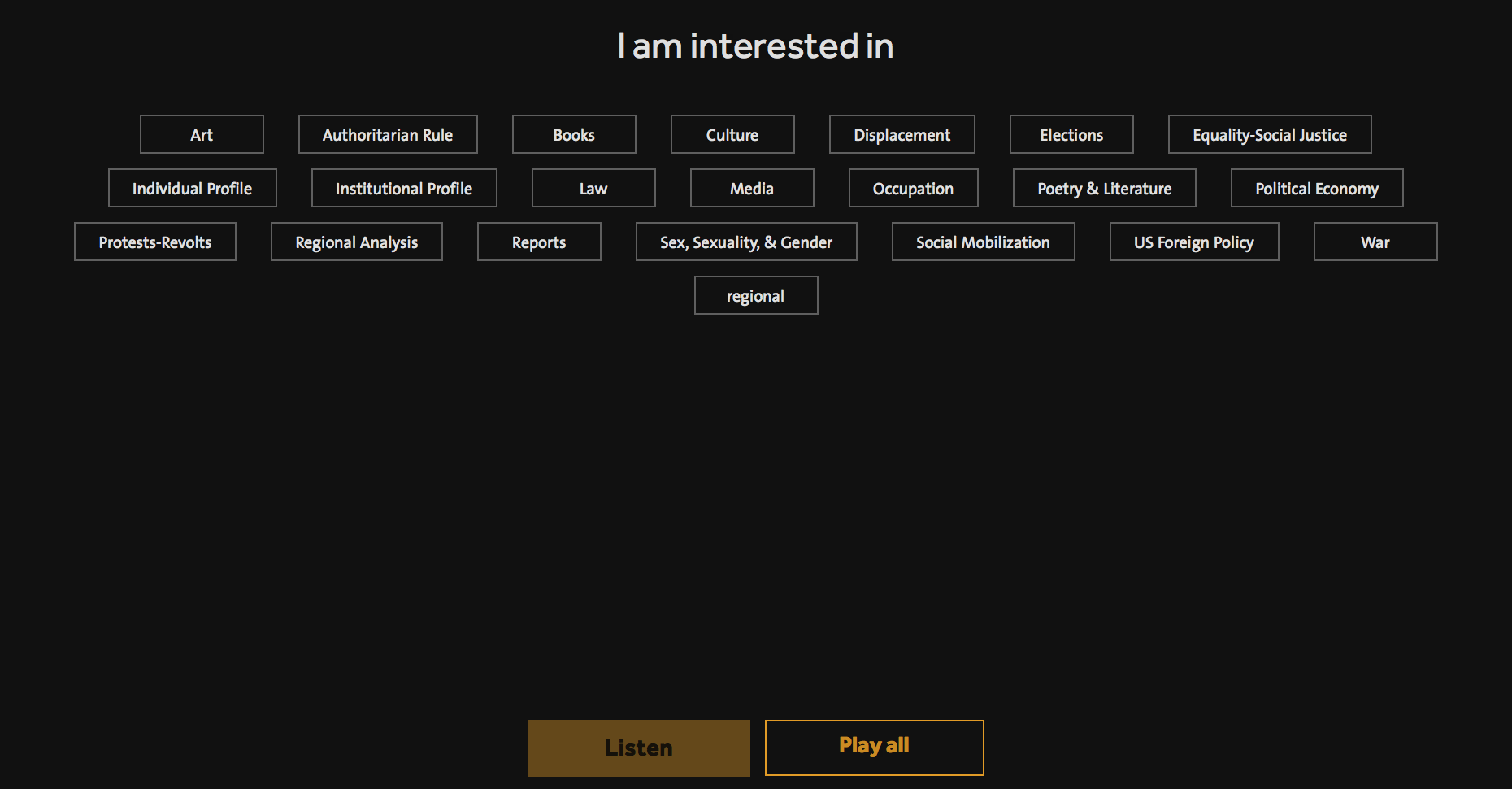

Your Own Private Page Login and Customization on Status!

We are very excited to announce that now you will be able to login and do multiple things such as save intereviews and share folders with friends or your students if you are an educator. The sign in process can occur through your Gmail or Facebook account, as well as generically via your own email account. All of Status content will be at yoru fingertips!

Customize Your Page to Your Heart`s Content!

Forthcoming Foci

In future issues of Status, you can expect that we will continue to grow our pluralistic content as we explore fault-lines across the region—including revolutionary art, sectarianism, refugee experiences, architecture, media practices, graphic novels, women’s rights movements, student organizing, underground music, conflict coverage, transnational solidarity, and much more.

Listeners can also expect a host of new shows on Status that will be local in focus, thematic, or offer a unique format. For instance, we are actively developing a satirical program that gets at the contradictions in regional dynamics using parody and humor.

An additional area of content diversification is language. One of the important benchmarks for our content development is the expansion of our programming to include more languages, more often. In the beta version of Status, we have achieved a true feat by having our Arabic original programming match the English in volume! We consider this a testament to two priorities: 1. Expanding our communication and commitment to foregrounding experiences from the region in domestic languages, and 2. Responding to the seismic shift in the flow of information. Our next step is to make as much of our content as possible available in both languages and to expand our coverage to other regional languages.

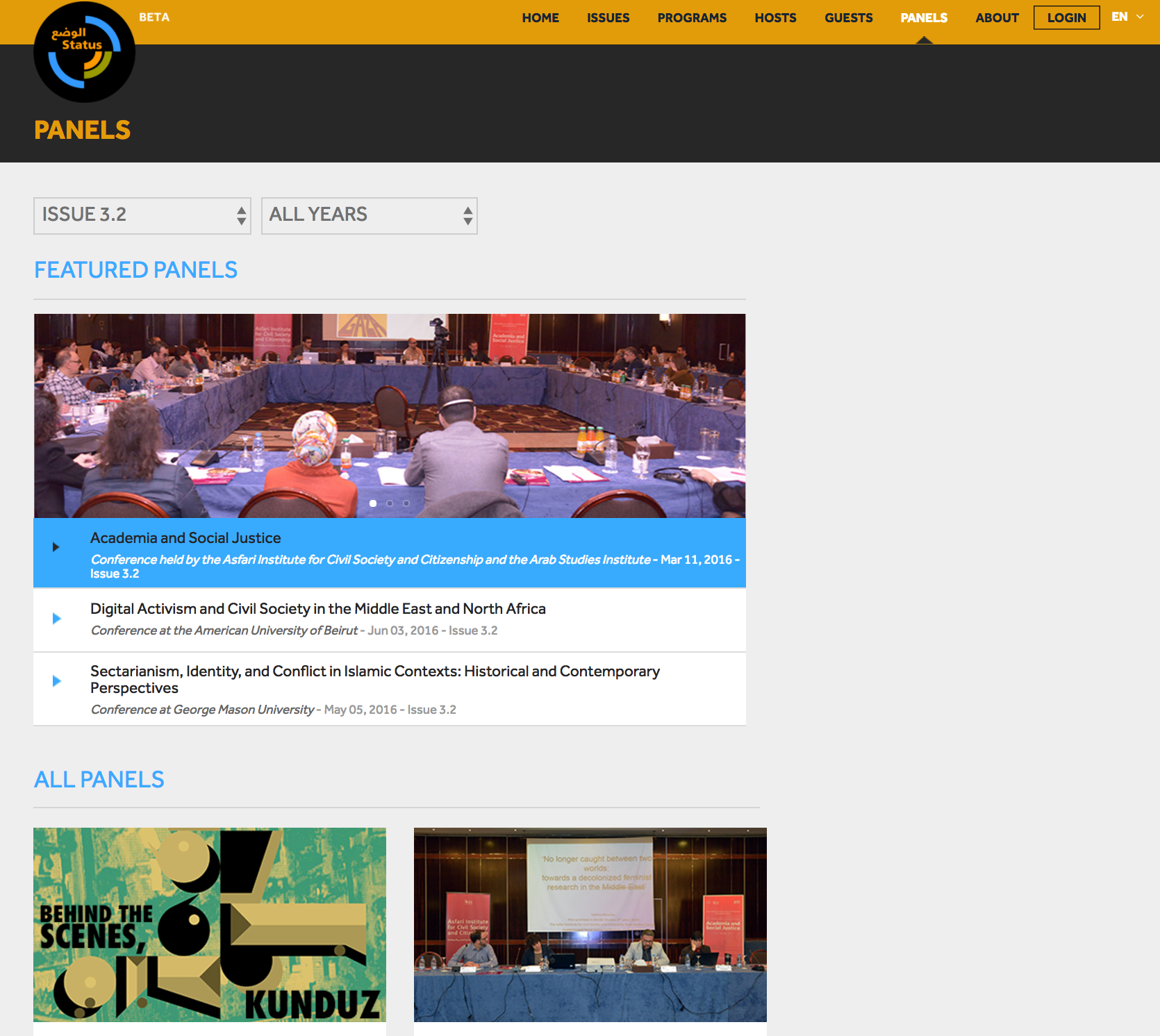

Finally, we are unabashedly committed to making Status a platform that moves regional voices to pedagogy and connects scholarship to regional actors. The content on Status is a testament to abandoning of the “cult of expertise” and a commitment to the interchangeability of media and audience—at once, the audience produces the media and the media themselves are audiences. Academic and activist panels such as conference events, workshops, or lectures dedicated to thinking collectively about the issues that affect the peoples of the region are opportunities for immensely valuable public exchange. For this reason, Status is home to a growing database of such panels that are made available in audio and/or video formats. From academic`s role in social justice to digital activism and civil society, and from sectarianism and identity in regional conflict to decolonization, we are making these panels that take place across the world available for all to engage with.

With the platform’s home being cyberspace, Status takes advantage of the computational innovations that render the experiential multidimensional, shift epistemic centers by creating alternative archives, offer novel ways to represent the self, and expand opportunities to move beyond the normative. We are convinced this experiment we call Status will be a most remarkable, or at least unique, journey for media and the region. We invite you to join us on this journey.

Ahlan Wa Sahlan to Status الوضع !