This weekend, the Modern Language Association`s (MLA) Delegate Assembly voted against a detailed, closely-argued, and voluminously documented resolution to support the boycott of Israeli academic institutions (79 for, 113 against). A few minutes later, the same body proceeded to pass a brief, four-paragraph anti-boycott resolution (101 for, 93 against), which did little more than assert that “the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel contradicts the MLA’s purpose to promote teaching and research on language and literature.” Barring anything unexpected, the latter resolution will now go to the MLA’s full membership for a vote; should it receive majority support and approval from at least ten percent of the organization’s approximately 24,000 members, it will become the formal expression of the MLA’s membership. The MLA, in other words, is on the verge of joining the odious company of Canary Mission and various federal and state legislators working to make certain that even the discussion of the Boycott, Sanctions, and Divestment (BDS) movement will be banished from educational institutions.

Of course, within moments, the word went out: "DEFEAT for BDS!" But even in light of these results, I am going to insist, however perversely, that something substantial was accomplished at the MLA Convention this past weekend. It is not every day that a large and influential institution like the MLA—which claims to represent humanist values and actually does represent, as a professional organization, scholars of language and literature from throughout the world—declares publicly: no, in fact, we don`t mind being complicit with injustice. In fact, we like our complicity so much that we are willing to embrace it and endorse it. And no, in fact, we do not care about our Palestinian colleagues—or rather, we care more about protecting the rights and privileges of ourselves and people we consider to be like ourselves, even at the expense of the rights and privileges, and if need be the lives, of those we consider to be, for whatever reason, different from ourselves. There is a word for this sort of thinking. It is called racism.

In other words, it is not every day that a professional organization like the MLA declares its allegiance to upholding injustice and structural racism. These sorts of moments of revelation are extremely rare, and only ever come in response to struggles in the name of justice, carried out by groups such as MLA Members for Justice in Palestine, which worked tirelessly for several years to draft, put forward, and rally support for the boycott resolution. The veil is lifted. It`s up to all of us now to decide how we choose to interact with such an institution.

Please don’t just take my word for it. The words of those who opposed the boycott resolution and advocated for the MLA to refuse its support to the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel condemn them out of their own mouths. Two quotes from an article claiming to cover the MLA’s “boycott debate” (which in fact served largely as a mouthpiece for anti-boycott arguments) will suffice.

First: “It is a mistake to think that the vote [in favor of the boycott] is a way to express sympathy for the abuse of Palestinians because what is on the table is an academic boycott of Israeli universities, the institutions at which many Arabs gain their education,” declared Rachel S. Harris, associate professor of Israeli literature and culture in the program in comparative and world literature at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In other words, according to Professor Harris, the mere fact that Palestinian citizens of Israel are “allowed” to attend Israeli universities (while suffering from the same sorts of discrimination and unequal citizenship as all Palestinians citizens of Israel) means that those who support the boycott of Israeli academic institutions do not really care about Palestinians. Apply the same reasoning to any oppressed minority group in the US—“They should be happy that we let them go to school here!”—and its explicit racism, not to mention its explicitly Trumpian overtones, become immediately clear. One can hardly imagine the same logic being used against those who—quite rightly—called for and supported boycotts of North Carolina and Mississippi after those states’ legislatures passed laws allowing discrimination against gays, lesbians, and transgender individuals. (“Well, LGBTQ people are allowed to attend school in North Carolina, so if you’re calling for a boycott of that state, you clearly don’t care about LGBTQ people”).

Second: “The key argument is it ain’t our business,” says Cary Nelson, Jubilee Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. (Readers may recall that University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is the university that was censured by the American Association of University Professors and forced to pay a nearly $1 million settlement for its violations of the academic freedom of Steven Salaita.) Nelson, one of the avowed leaders of the anti-boycott movement within the MLA who has displayed an attitude towards academic freedom that is selective, to say the least, should at least be given credit for honesty here. In openly declaring that the injustices being committed in our name and with our money against our academic colleagues in Palestine simply “ain’t our business,” he at least is straightforward enough to state the true grounding of the anti-boycott argument: certain sorts of injustice (against Palestinians) just are not worth bothering about, and the status quo will do nicely. It remains to be seen how history (not to mention literary history) will judge such callousness.

As it happens, I was at the MLA convention this weekend (though not the Delegate Assembly meeting itself, so I am indebted to the accounts of those who were in attendance there). I had the privilege, the day before the MLA vote, to take part in a panel with a number of valued colleagues, focusing on the issue of dispossession in West Asian literature and culture, with a particular focus on Palestinian and Kurdish film and literature. The fact that such a panel could exist amidst the sea of whiteness that still constitutes too much of the work of the MLA has to do with the struggles of many who have gone before, whose worked has helped to open up such spaces. Such struggles continue (although the question of whether the MLA is still worth struggling over, or whether our work now is to create alternative institutions to replace such corrupt ones, will become a major point of discussion for the future). Suffice it to say that for me, the idea of engaging in scholarship and teaching related to Palestinian literature and culture without doing whatever I can to support the call for the cultural and academic boycott of Israel put forth by the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel is unthinkable. The fact that my primary professional organization has chosen to violate and refuse this call represents, to me, a failure that is at once ethical, political, and intellectual.

My own few remarks at the conference were focused on the question of comedy and resistance in Palestinian and Kurdish cinema, with specific reference to two films: Bahman Ghobadi’s Half Moon (2006) and Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains (2009). “Comedy,” of course, is not a word that springs to mind when one considers questions of dispossession, statelessness, forced migration, apartheid, genocide—all of the tragic issues represented by Palestinian and Kurdish visual culture. And yet—or so I am prepared to argue—comedy, as both a cinematic and a rhetorical form, has been a powerful aspect of recent films by Palestinian and Kurdish filmmakers, and is well represented in these two films.

The paper I presented, and the larger work it represents, is an attempt to carry forward an argument that I have begun elsewhere, and has its genesis in a moment from the work of the great social theorist Theodor Adorno. In his essay “Commitment,” Adorno warns against works of art, even well-meaning ones, that “turn suffering into images” and thus cannot help but also turn this suffering into a form of enjoyment for an audience to consume at its leisure. In such sentimentally “tragic” works, the victims of suffering, Adorno writes, “are used to create something, works of art, that are then thrown to the consumption of a world which destroyed them. The so-called artistic representation of the sheer physical pain of people beaten to the ground by rifle-butts contains, however remotely, the power to elicit enjoyment out of it.” What I am calling the comic mode is precisely a resistance to this mode of viewership.

The biggest danger for a complicit audience is that the sheer fact of viewing a film that represents suffering in a tragic mode can come to seem like an act that somehow addresses the suffering that has been represented. One goes to view suffering, one cries one’s share of tears at the “tragedy,” one goes home feeling cleansed and somehow superior to those too hardened or too unaware to view the latest representation of suffering in Palestine or Kurdistan, or in any of the many other sites of injustice on the earth. The laughter found in the films I identify as embodying a comic politics interrupts this too-easy tragic narrative, and disturbs the viewer’s desire for simple pathos, for a catharsis that allows one to return home feeling chastened but clean, ready to resume life as usual. In place of any comfort, even the comfort afforded by the simple, purging tears of tragedy, such films leave us shattered. They also present us with an ethical choice: while such films are as far from the didacticism of propaganda as can be imagined, they nevertheless demand from us some response, if only as a way to come to terms with the desolation of their effect.

Suleiman’s The Time that Remains—like his remarkable body of work as a whole—is particularly notable in this respect. Suleiman uses comedy to powerful effect, from broad slapstick to subtle visual comedy, as well as forms of in-jokes that call to different parts of his audiences in different modes and manners. Like the rest of his filmography, The Time that Remains represents not only the dispossession of Palestinians, but also various attempts to return. By using comedy to address the deadly business of dispossession and the struggle to return, Suleiman’s remarkable body of work manages to invoke a tragic past without falling prey to simplifying, idealizing, or sentimentalizing this past.

I have written about the film at length elsewhere, so here, as I did in my MLA paper, I will make reference to just one sequence that provides a fine example of Suleiman’s brilliant patchwork comic vision, in which comic timing exists uneasily alongside violence—violence which is always potential, except when it is actual. In this sequence, Suleiman’s eponymous character, identified in the credits only as “E.S.,” is observing life in Ramallah between visits to his mother’s hospital room, where she is approaching death. In doing so, the film captures the everydayness of the occupation, along with the everyday acts of resistance that make it possible to go on. Unlike Suleiman’s previous and best-known film, Divine Intervention, there are no ninja heroines here, but there is the matter-of-fact bravery of a young mother with a squeaky baby carriage facing down Israeli soldiers in Ramallah.

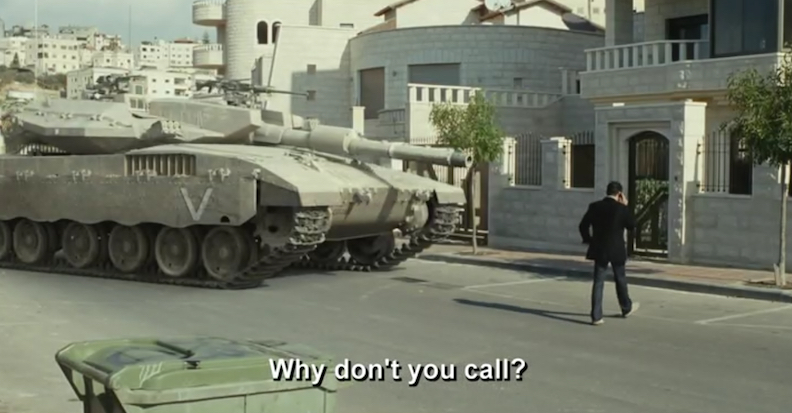

The sequence culminates with a long scene in which the gun of an Israeli tank follows, at extremely close range, a young Palestinian man as he steps outside his house and takes a bag of garbage to a trash can on the opposite sidewalk. It is an incredibly evocative visual metaphor: anyone who has witnessed the work of the occupation in places like Ramallah can attest to sometimes feeling as though there is in fact an Israeli tank for every Palestinian.

But Suleiman succeeds in turning what could easily have become a tragic scene into (also) brilliant physical comedy: as the man is about to step through his front gate, the musical ringtone on his cellphone sounds, and the tank gun is forced to follow him, bobbing and weaving, as he walks back and forth carrying on his conversation with a friend (“Where you been? Why don’t you call?...Listen, there’s a party at the Stones tonight….Everyone’ll be there. You should come.”) When he finally hangs up and goes inside, the tank gun swivels to take aim at the garbage can. But what at first sounds like shots being fired on the soundtrack is revealed to be, as this scene dissolves into the next, the throbbing electronic music of the party at The Stones.

What is evoked by the comedy here is the power of youth culture, especially as embodied in music, which becomes increasing central as the story of The Time that Remains, which begins with the moment of the Nakba of 1948, moves into the present. We see it in the scene immediately following the one I have described, at The Stones, a club whose name simultaneously evokes pop culture and also the stone-throwing resistance of the intifada. Outside is the Israeli army, attempting to impose curfew, using essentially the same words as those we heard coming from the occupying army in Nazareth that first placed the city under military control at the beginning of the film. E.S.’s father and his young comrades resisted curfew, as did the young E.S. and his friends; the partiers at The Stones offer their own form of resistance. If you spend all night dancing in a club, are you obeying the orders to stay off the streets after dark, or are you resisting curfew in a way that the law and soldiers cannot quite name?

But what does any of this have to do with the boycott? And why talk about comedy in the face of the MLA’s odious actions? What occurred to me, as I thought about the fact of presenting a paper on Palestinian cinema the day before the MLA was to vote on the boycott, was that in fact, the BDS movement, like Suleiman’s cinema, may indeed be an example of politics working in the comic rather than tragic mode. In part, this has to do with what its opponents refuse to acknowledge, which is that BDS represents a wholly positive, non-violent form of resistance, an attempt to both stand with our colleagues in Palestine and to break the horrific and violent form of stasis that defines the ongoing situation in Israel-Palestine.

But there is equally, for those of us who have been involved in the BDS movement from its inception, something absurdly comic, in the Suleimanian sense, about the way opponents have responded to the call to boycott. The 2005 call from Palestinian civil society groups came, it is probably fair to say, from a sense of desperation and desolation. It came in the wake of the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) decision of July 2004, which declared that the wall being built by the Israeli government in the occupied territories was a clear violation of international law. Many of these same civil society groups had poured time and resources and enthusiasm into bringing this case to the ICJ, in hopes of achieving such an outcome. But in the event, this overwhelming decision by the principal judicial organ of the United Nations achieved exactly nothing: international law was not enforced, the wall went up to do its savage work, and no one was ever held accountable. The nothing which followed was palpable and painful.

When the boycott call went out exactly one year later, its underpinning—which is also the motivating force of the BDS movement, the thing that makes it an international grassroots popular movement—was the idea that we who constitute the movement have no one else to turn to but ourselves. No country, no international organization, no court, no law, no institutions of any kind have done a thing to end the occupation of Palestine and the immiseration of Palestinians. All we had, and have, are ourselves; we are a movement because we say so, and because we are willing to do what little we can to change things, including asking our professional organizations to end their complicity, as humanists, with the dehumanization of the occupation.

A decade and change later, and here we are, said to pose an existential threat to one of the greatest military powers on the earth, the object of congressional and state legislation and international opposition, addressed by name by US presidential candidates who say that stopping us ranks among their major priorities. Within the MLA itself, a dozen “Past Presidents” emerged from the privileged precincts of their named professorships and emeritus statuses to write an open letter opposing any attempt to stand with our colleagues in Palestine. As a supporter of BDS, one sometimes feels a bit like the Suleiman character whose movements are shadowed by the tank gunner. Are they really so scared of us? Do they really need such heavy artillery? The absurdity of it all—the rhetorical overkill, the money and political firepower brought to bear against us, the mischaracterizing of a people’s grassroots movement for justice as some sort of organized hate group, the blacklists, the fearmongering—if there weren’t so much at stake, one would be tempted to call it comic.

But BDS is politics in a comic mode in another way, one closely related to Suleiman’s cinema, in that it deals with the question of the everyday lived experience of Palestinians: not with the question of change at the macropolitical level, but with the question of lived justice—in our limited case, justice for Palestinian academics and students. The slow passing of time, the scenes where little or nothing happens, until something (almost always bad) does—this is what Suleiman’s comic vision represents. It rhymes with a question once asked by Slavoj Žižek: What goes on in Palestine when nothing goes on in Palestine? In other words, when Israel-Palestine is not in the news, as it has been of late—no new “peace initiative,” no UN resolution controversy, nothing that counts here as “newsworthy”—what is the lived experience of Palestine? The answer, of course, is the slow, painstaking, stifling, death by a thousand wounds that is settler colonialism. This is the level at which both Suleiman’s cinema and the BDS movement do their work.

Most importantly, BDS works in a comic mode because it does not generally fall back upon the tragic sentimental mode. Of course, it derives its basis from an enumeration of Palestinian suffering; otherwise, there would be no cause for justice. But it does not stop there, in the way that our usual politics—call it the politics of consciousness raising, of accumulating and disseminating alternative information, of fact-checking, of letting people know the “real story”—too often does. It does not let us take satisfaction in our willingness to simply look at suffering; it moves to the next step, by asking: What are you prepared to do to make these bad things end?

The BDS movement, and in particular the movement for a boycott of Israel academic institutions, started in many ways from a place of relative despair. And we humanists are all too ready to be pessimistic and self-deprecating about how little the things we do for a living really “matter” in the face of “real” politics. But the response that BDS has drawn, even if it leads to the delaying or defeat of particular proposals or resolutions at particular moments, is still ultimately hopeful—comic rather than tragic. It is a reminder that those of us engaged with what I choose to call cultural politics may indeed be more powerful than we think. It also suggests that we literary and cultural critics need to continue to fight to liberate the power that resides in cultural texts from the grip of those who see the work of criticism as by definition “apolitical”—which, of course, means the politics of endorsing the status quo. To “do literature” holds the potential to also do justice, if we choose to take up the fight to make this so.

All this rhymes, in fact, with the final scene of Suleiman’s The Time that Remains. As our attention shifts in the film’s final sequence, we pass from old age (E.S. and his mother) to youth. (So too, we must hope, will organizations such as the MLA, as the vampiric power of the generation that is at the forefront of the anti-boycott movement ultimately and inevitably gives way to a younger generation of scholars and students that is taking enormous steps towards bringing solidarity with our Palestinian colleagues to pass). The final moments of the film focus upon a group of three young men, recognizable partisans of hip-hop culture, who seat themselves on a bench at the upper right hand corner of the frame. Eventually, another young man walks into the frame and moves towards them, handcuffed to a much smaller and slighter Israeli policeman. His friends stand to greet him, and when he gets alongside them, he yanks on the handcuffs, forcing his captor to come to a halt while all four youths exchange pounds and hugs and cigarettes. Finally, after flashing a last V for Victory, he gives the policeman another yank to move him along, leading him as if the handcuff was a leash.

Once again, we end, as does the film, on a moment of youthful resistance (accompanied by a soundtrack that emphasizes the will to fight on—as the screen goes black, we hear, in English, the opening lyrics of “Stayin’ Alive,” performed by Yasmine Hamdan). Watching the film five years ago, I was struck by how resonant this image was amidst the uprisings of 2011; today, in what feels like a much darker political moment, but one also marked by the real progress achieved over the past decade by movements for justice such as BDS, it seems even more so. One of the most recurring images from various liberation movements has been that of upraised arms breaking free of chains. Suleiman leaves us with a similar but slightly different image of resistance. If you find yourself chained to your oppression—whether that power is embodied by an occupying force, an authoritarian president, or an unaccountable and complicit institution—grab hold of your handcuffs and pull. It may turn out that you’re stronger than you thought.