City of Mirages: Baghdad 1952-1982. The Center for Architecture, 536 LaGuardia Place, New York, NY, 22 February – 5 May 2012.

City of Mirages: Baghdad 1952-1982 is an exhibit of design work produced by world-famous architects and firms for the booming Iraqi capital during the mid-twentieth century. Beginning from the year that the Iraq Development Board was established to channel seventy percent of state oil revenues into modernizing schemes for national development, the exhibit traces a thirty-year timeline of foreign architectural practice in Baghdad.

Pedro Azara of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona and his curatorial team selected thirteen key projects to represent significant aspects of, and pivotal moments in, the history of how modernist and postmodernist architects from outside Iraq planned and imagined Baghdad as a modern city. Over the course of these three decades, state power alternated among five different regimes, all of which played a part in commanding the direction and scope of city making from the top down. With each new government, the broad agenda of urban development shifted somewhat; it is partly due to this volatility that more than half of the projects presented in this exhibit were never realized on the ground.

Thus the title City of Mirages is entirely appropriate, as the image of Baghdad memorialized in the space of the exhibit was only ever a mirage. Together, the elegant arrangements of sketches, renderings, and models on display here reveal a projection of the Iraqi city that oil promised to build, but never did. During the 1950s, many of the master architects that the Development Board commissioned late in their careers to create landmark projects throughout the capital accepted the opportunity with delight, viewing it as an opportunity to leave their signature upon the cradle of civilization.

For several of these star-architects, Orientalist fantasies and modernist doctrines informed their designs well before they ever set foot in Baghdad to examine the site and discuss the requirements of the commissioning board. For example, Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs for an opera house, cultural center, central post office, and memorial on the Tigris River stand as outright evidence of Orientalism’s stranglehold over some designers. Inspired by the epic tales of Alf Layla wa Layla, Wright’s plans for Baghdad’s modern landmarks translate his fantasies of the Orient into a theme-park assemblage of buildings intended to recall ancient ziggurats and genie’s lamps.[1] For many, it is no wonder that these particular designs were never realized.

[Frank Lloyd Wright, Plan for Greater Baghdad, 1957. Image via Wikipedia.]

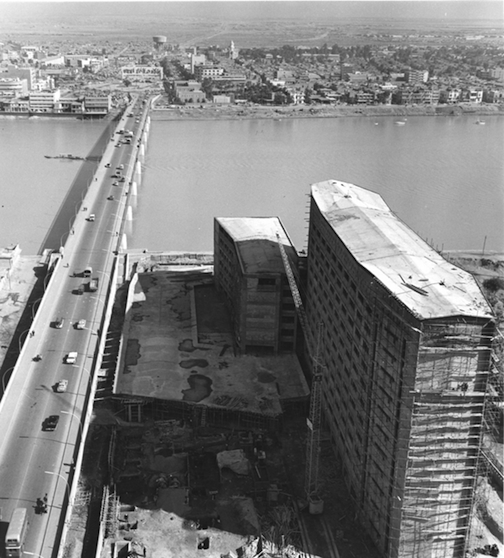

Modernist architects like Josep Lluis Sert, Le Corbusier, and Gio Ponti approached the challenge of designing for Baghdad with relatively less whimsy. Rather, each reproduced his own signature style in their building designs, the originals of which can be located in other cities across the globe, from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Chandigarh, India to Milan, Italy.[2] Construction of Sert’s US Embassy was completed, and Gio Ponti’s Ministry of Development well under way, prior to the July 14 Revolution of 1958, which replaced the regime of Nuri Al Said and Iraq’s monarchy with a new republic under President Abdul Karim Qasim.

[Gio Ponti, Ministry of Planning under construction, Baghdad, 1958. Image courtesy of Dr. Khaled Al-Sultany.]

On the other hand, Le Corbusier’s design for an Olympic stadium and sports complex remained just a stack of papers for many years after the architect passed away. It was not until Iraq’s Ba’athist government decided to partially realize his design (the last completed in Le Corbusier’s prolific career) that the building was constructed and opened as the Saddam Hussein Gymnasium in 1980.[3]

[Left: Le Corbusier, Saddam Hussein Gymnasium, Baghdad, 1980. Image courtesy of Pedro Azara.

[Left: Le Corbusier, Saddam Hussein Gymnasium, Baghdad, 1980. Image courtesy of Pedro Azara.

Right: Model of Le Corbusier’s Olympic Stadium, City of Mirages Exhibit, 2012. Image by Mona Damluji.]

Constantinos Doxiadis and Walter Gropius tackled some of the more difficult social and urban problems in Baghdad to develop modernist plans for a housing scheme and central university campus, respectively. These designs adhered to the classic brutalist aesthetics of bare concrete and brise soleil reproduced around the globe; however, the scope and scale of their projects required more research on their parts than architects commissioned for stand-alone buildings. Doxiadis Associates and The Architects Collaborative (TAC) went further than most of their contemporaries to analyze and address the specificities and demands of the local context, though certainly there were problematic aspects of their work that could arguably be traced to undergirding Orientalist assumptions and modernist simplifications.[4] Unlike the other Development Board commissions, construction on these projects continued to some extent under Qasim’s republic, resulting in the partial completion of the modernist visions for Baghdad. Today, TAC’s university tower still rises above the Al-Jadriya campus, while Doxiadis’ housing blocks are subsumed by the dense growth of Sadr City.

.jpg)

[Doxiadis Associates, Housing Program for Iraq, 1955. Image courtesy of Pedro Azara.]

Perhaps the foil to the City of Mirages presented here is the grand portfolio of work by modern Iraqi architects: the buildings that stand as the true architectural spectacles in the lived city. In conversation with the craftsmanship of Baghdad’s ustas (master builders) and inspired by the possibilities of reinforced steel construction, Rifat Chadirji, Mohammad Makiya, Hisham Munir, and many others inscribed the city with their unique visions in brick and concrete.[5] For readers interested in pursuing these issues further, Dr. Ghada Al-Siliq (University of Baghdad) will be giving a lecture on May 1st titled "Architecture in Baghdad, Then and Now" at the Center for Architecture.

[Rifat Chadirji, Central Post Office, Baghdad, 1976. Source: Aga Khan Award for Architecture, archnet.org.]

One of the most remarkable aspects of the exhibit is the work that architecture students at the University of Baghdad and School of Architecture of Barcelona put into the material construction of the imagined schemes, that is, the making of the marvelous models featured throughout the exhibit. Seen in three-dimensions, the architectural landmarks of Baghdad (even those never built) stimulate the viewer’s imagination. Dr. Ghada Al-Siliq of the University of Baghdad, along with colleagues Saad M. Hmoud and Bilal Samir Ali, assembled a team of twelve Iraqi architecture students to produce the spectacular centerpiece: a sprawling model of the entire city, illuminating the location and urban context of the many projects seen throughout the exhibit. Flanking the large site model are two video screens juxtaposing looped sequences of archival images of the remembered and the contemporary city.

[Dr. Ghada Al-Siliq and architecture students at University of Baghdad building the model of Baghdad

for City of Mirages Exhibit, Baghdad, 2008. Image courtesy of Dr. Ghada Al-Siliq.]

[Model of TAC Baghdad University buildings, City of Mirages Exhibit, 2012. Image by Mona Damluji.]

Today, the constructed building projects featured in the exhibit have suffered in some ways from the US invasion in 2003 and nine years of ongoing violence under occupation. The exhibit gestures towards the “deteriorating” conditions of Baghdad’s built environment in a passage at the entry and the montage of recent images from the city; however, the curators have not gone so far as to document the full extent of the damage in detail. This is the work of dedicated architectural historians at the University of Baghdad and elsewhere, who courageously traverse the city in order to capture and record what is possible.[6] In 2004, UNESCO and the Politecnico University in Milan initiated a cultural heritage project to rehabilitate Gio Ponti’s Ministry building, which was badly damaged in the post-invasion looting; yet such spectacular gestures towards international reconstruction projects can distract from the real damage wrought by the ongoing violence. Countless homes, schools, hospitals, bridges, and neighborhoods in Iraq have been destroyed, and after all, Baghdad’s cultural heritage is far more than its landmark buildings.

[Gio Ponti, Ministry of Planning, Baghdad, 2003. Image by Simon Norfolk, “The Ministry of Planning,

Baghdad 19-27 April 2003” from his series "Scenes from a Liberated Baghdad."]

An addendum to the exhibit’s catalogue of pristine projects rendered visible as lines on trace paper is the long narrative of war in Iraq. The deterioration of the quality of life for Iraqis since the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, followed by the first US invasion in 1991 and thirteen subsequent years under UN sanctions, and capped by the ongoing US occupation, is perhaps most visible in the ruined and fragmented built environment.[7] Indeed, the damage of these last four decades manifests itself in every aspect of daily life in Iraq, from compromised health care and personal security, lack of access to essential needs like clean water and housing, lack of provision of basic services like electricity and trash collection, to the unavailability of decent jobs and the fundamental struggle for a sense of personal dignity.

Notes

[1] See J. M. Siry, “Wright`s Baghdad Opera House and Gammage Auditorium: In Search of Regional Modernity,” The Art Bulletin 87:2 (Jun 2005): 265-311, and M. Marefat, “Wright’s Baghdad,” in Frank Lloyd Wright: Europe and Beyond (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

[2] See S. Mehdi, “Modernism in Baghdad,” City of Mirages: Baghdad 1952-1982 [Exhibition Catalogue] (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2008): 81-89, and S. Isenstadt, “Faith in a Better Future: Josep Lluis Sert`s American Embassy in Baghdad,” Journal of Architectural Education 50:3 (Feb 1997): 172-188.

[3] See M. Marefat, “Mise au Point for Le Corbusier’s Baghdad Stadium,” Docomomo 41 (September 2009): 30-40.

[4] For a critical analysis of the Doxiadis Associates housing scheme for Iraq, see P. I. Pyla, “Back to the Future: Doxiadis`s Plans for Baghdad,” Journal of Planning History 7:1 (February 2008): 3-19; for a descriptive overview of Gropius & TAC design for Baghdad University, see M. Marefat, “From Bauhaus to Baghdad: The Politics of Building the Total University,” TAARII Newsletter (Fall 2008).

[5] For discussions on Iraqi architects, see M. T. Bernhardsson, “Visions of Iraq: Modernizing the Past in 1950s Baghdad,” in Modernism and the Middle East (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008) and H. Nooraddin, “Globalization and the Search for Modern Local Architecture: Learning from Baghdad,” in Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An Urban Kaleidoscope in a Globalizing World (Routledge, 2004); for a well-illustrated chronicle of the work of Baghdad’s craftsmen and the early period of modern building practices in the city, see Caecilia Pieri, Baghdad Arts Deco: Architectural Brickwork 1920-1950 (Cairo and New York: American University of Cairo Press, 2010).

[6] In 1991, the Presidential Administration under Saddam Hussein established the Reconstruction Studies Center at the Department of Engineering, University of Baghdad, in order to conduct and publish research following the US invasion. Dr. Suad Al Azzawi served as director until the center was forced to close in 2003.

[7] See G. M. R. Al-Silq, City of Stories, (Iraqi Cultural Support Association, 2011) and M. Damluji, "Securing Democracy in Iraq: Sectarian Politics and Segregation in Baghdad, 2003-2007," TDSR 21:2 (2010): 71-87.