The multifaceted work[i] of Pier Paolo Pasolini has largely been examined, and is still inspiring different disciplinary, epistemological, and political explorations and reflections inside and outside of Italy. However, his particular filmic and poetic engagement with Israel/Palestine has oddly attracted little attention.

Pasolini writes his poemwork Israele (1964) during one of the most intellectually and humanly intense moments of his life. A lawsuit is in progress against him for "insulting the State religion" for the film La Ricotta (1963). He has been back from his first trip to India, which leads to his interest in the "Third World." As early as 1962, this interest takes him to sub-Saharan Africa and finds its artistic expression at least in Notes for a Film on India (1968) and in Notes Towards an African Orestes (1970). He has finished The Anger (1963), a film montage of media reports in which Pasolini manifests his ethical and political sensitivity for the independence struggles from colonialism and the international revolutionary ferment that in those years united the different African, Asian, and American situations.[ii] He shoots Love Meetings (1965) and works on the script of The Savage Father: a movie, never made, on the relationship, immediately after independence from colonialism, between a Western teacher and his class of African students. Meanwhile, the production machine that leads to his filming The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), and his trip to Palestine, is already underway.

In the ten pages of Israele, Pasolini assembles his observations and experiences from the trip to Palestine and constructs his political poetics through a series of oppositions between Jews and Arabs. He uses the latter term when referring to the Arab population in Palestine without ever employing the word “Palestinians” (he will do it later). As will become clear in a later work of his, the idiosyncratic film Location Scouting in Palestine,[iii] what “Arabs” embody for Pasolini is a marginal premodernity, a prebiblical Palestine, to use his own words. However, my interest does not lie in probing Pasolini`s questionable classifications and the dichotomy between tradition and modernity (although I will come back to this point).[iv]

Rather, what makes worthwhile revisiting Israele is Pasolini’s engagement with Israel’s paradoxical modernity in a very peculiar poetic way, as we will see, and in a very peculiar historical moment. In fact, this engagement takes place in the same years when interrogating the relationship between the Holocaust and the state-institutionalized Zionist settler colonial practices in Palestine still looked like a taboo among many European and Western intellectuals, even among the anti-colonial ones. Maxime Rodinson’s and Edward Said’s pioneering works on the intertwining between political colonial and settler-colonial forms, the concentrationary extermination of Jews in Europe, and the dispossession of Palestinians had not appeared yet.

In his poem Israele, Pasolini observes a few “Arabs” strolling along a seafront, probably in the new Tel Aviv: a seafront that recalls other places in Asia and Africa, like Calcutta or Nairobi. They wear "blue jeans color carogna, e magliucce bianche, aderenti, sudice – come algerini condannati a morte" [blue jeans the color of carrion, and filthy, clinging sweaters—like Algerians on death row].

A few pages later, there are a couple of lines on “the little ones of the Arabs,” described like this:

I piccoli degli arabi, essi sì, ridono, ridono scioccamente, con una struggente stupidità, come i nostri poverelli; i cuccioli del popolo affamato, le bestioline con gli stupendi occhi umani [Now the little ones of the Arabs, they laugh, they laugh idiotically, with a heart-rending stupidity, like our own poor folk; the cubs of the hungry masses, little critters with stunning human eyes].

“Animal-humanist” empathy and identification from the heretical Orientalist.

Then, in a play of juxtapositions and contrasts that mark Israele, Pasolini verges on a modernity quite different from the other modernities that he deals with: namely, the new Jewish citizens of Israel, the traumatized brothers:

Non ce l’avete fatta più, fratelli—fratelli maggiori per dolore—segnati dalla grandiosità del male, e siete scappati quaggiù, siete venuti a raccogliervi quaggiù, come quando si vuol morire e non morire, ammucchiandovi come pecorelle che credono il calore delle sorelle coraggio. Il trauma, così passato di moda oggi nel mondo, di venti, di venticinque anni fa, qua lo conservate, avete cercato quest’area marginale, per preservarlo, istituzione di origine divina! [You couldn`t cope anymore, brothers – older brothers by pain—marked by the grandiosity of evil, and you escaped over here, you came to gather together over here, like when you want to die and not die, piling on top of each other like little sheep that believe the heat of their sisters to be courage. The trauma from twenty, twenty-five years ago, now so out of fashion in the world, you preserve it here, you looked for this marginal place, to preserve it, institution of divine origin!]

Drawing closer, his proximity turns into transference and transposition:

Tornate, ah tornate nella vostra Europa. Un transfert tremendo di me in voi, mi fa sentire la vostra nostalgia che voi non sentite, e a me da un dolore che sconvolge ogni rapporto con la realtà. L’Europa non è più mia! [Come back, oh come back to your Europe. A tremendous transference of me into you, makes me feel your nostalgia that you don`t feel, and to me from an ache that shatters all relations with reality. Europe is no longer mine!]

Pasolini then continues on his journey from Tiberias toward the sea:

Ed ecco oltre gli ulivi israeliani, maculati di laboriosa polvere, le case di legno e latta, le felici bidonvilles [palestinesi]. Ma ecco anche, al centro della regione, come un convento benedettino in Ciociaria, l’edilizia concentrazionaria di un kibbutz [And now beyond the Israeli olive trees, speckled with hardworking dust, there are the houses made of tin and wood, the happy [Palestinian] shanty towns].

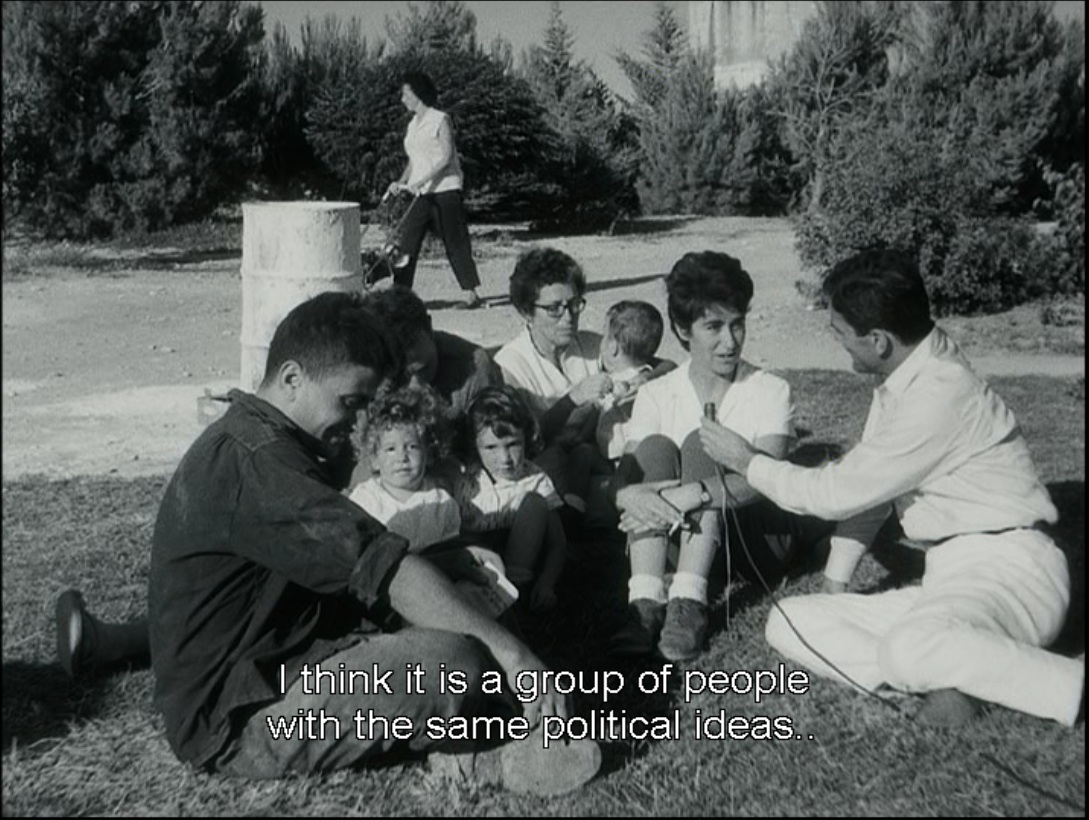

[Pier Paolo Pasolini interviews residents of a kibbutz. Image from the author`s archive.]

[Pier Paolo Pasolini interviews residents of a kibbutz. Image from the author`s archive.]

Pasolini`s identification with the survivors develops in a very particular way, by and through comparing the incomparable, by opposing the unopposable: political and heuristic heresy. The fact is, for Pasolini the architecture of the kibbutzim preserves something. Torn by his transference, he calls it “concentration-camp architecture.”

This is where Pasolini sets two elements side by side, without harmonizing them, without saying that they are the same thing—the kibbutzim are not concentration camps—without facile equations or syllogisms. He juxtaposes the founding architecture of socialist Zionism and the new Israeli political community with Nazi concentration-camp architecture (a term that Pasolini will later use to describe the Italian suburbs as well).

But there is more between these lines, a sort of juxtaposition within juxtaposition. This is what he writes in Israele to describe the kibbutzim:

Quattro magazzini, il silos, l’asilo, i dormitori come quelli di Dachau; e la pace di un villaggio del Centroeuropa, ambiguamente fusa con la pace coloniale [Four storehouses, the silo, the nursery school, the dormitories like at Dachau; and the peace of a Central European village, ambiguously fused with colonial peace].

How are we to interpret this enigmatic passage? The kibbutz bears the traces of twenty-five years earlier—the signs of modernity`s slaughter—and the signs of what he calls “colonial peace”. What does he mean by this expression? What kind of colonial peace is he talking about?

Pasolini apparently sets up a kind of “forbidden juxtaposition” in which two forms of apparently distant types of peace—as he himself writes—are ambiguously intertwined: the peace of Central Europe and colonial peace. What Central European peace? The peace in which the Holocaust took place? The peace that followed upon it. And what colonial peace? A vague peace of the colonies? Or the colonial peace of Israel?

Something ambivalent ties together the three elements of this juxtaposition within juxtaposition. The modernity of Israel takes the form of a paradoxical modernity that Pasolini feels bound to develop through a series of contrapuntal readings.

What we have is a contrapuntal reading of the relationship between the new state where Pasolini would have liked to set his Gospel and the concentrationary reason.

It is a contrapuntal reading of the kibbutz in a period when the European leftists were visiting the kibbutzim in order to witness the construction of a socialist utopia. Pasolini distances himself from the kibbutz as commune and from the fascination for Labor Zionism, reading the utopia against the grain, in juxtapositions, tracing out forbidden parallels, through a bitter disillusionment. This counterpoint is not present in Location Scouting in Palestine, perhaps, but then it surfaces after the fact, after the trip to Palestine, in his poetry.

In the end, he gives a contrapuntal reading of the same dichotomies that he used to interpret the worlds of Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean in the process of decolonization. Pasolini attempts to contrast the “premodern” laughter of the Arab children with the sad, “modern” faces of the Jews; the “premodern” farming techniques of the Palestinians to the industrious kibbutzim. But then he fails to radicalize this dichotomy as he does in other contexts. Something fortunately does not add up.

In Israele, Pasolini identifies both with the “premodern” Palestinian Arabs and with the Jews traumatized by what had happened in Europe twenty-five years earlier.

He rails against modernity, but then he notes how the colonial modernity of the kibbutzim in Palestine, in which many of the survivors were in the process of rebuilding their lives, preserves traces of the modernity of the Holocaust and of a mysterious “colonial peace.”

The juxtapositions and dichotomies used elsewhere, in other colonial Souths, blow up in his face, as it were, and he is unable to radicalize them. These dichotomies get jammed in Israele, leaving the traces of a contrapuntal thought that might well provide us with a new point of departure.

[i] Films, poems, novels, and public interventions in the Italian and European post World War II debates

[ii] It would be three years before Gillo Pontecorvo’s famous The Battle of Algiers (1966), one of the reference models from the scant Italian anticolonial intellectual film production, would address militantly and in Fanonian terms the decolonization of Algeria. On Pasolini, Pontecorvo and decolonizations, see C. Casarino, “The Southern Answer: Pasolini, Universalism, Decolonization,” Critical inquiry (2010).

[iii] The scouting in Palestine was supposed to provide Pasolini with the first ideas for the film The Gospel to St. Matthew (1964), but then the director preferred to shoot the film in Southern Italy.

[iv] These issues have been thoroughly examined and one need only reread a few pages from Luca Caminati`s Orientalismo eretico (“Heretical Orientalism,” 2007) to arrive at an excellent understanding of them, without resorting to facile reductionisms.