[This article is drawn from a paper presented by the author at the Vulnerability, Infrastructure, and Displacement Symposium held at University College London on 12-13 June 2019, as part of the panel on “Vulnerability and the (Built) Environment.” Click here, here, and here for other articles drawn from the same panel.]

The current habitability crisis, and the failure of progressive policies to think of ways that cities can adapt to different forms of displacement and resist the interrelated practices of expulsion, extraction, and externalization, are clear to anyone engaging with urban spatial practices. Displacement is a key characteristic of the urban present, requiring interrogations across different geographies, and with different methodological approaches. This article explores some of these dynamics by drawing on an ongoing research collaboration between Public Works Studio and The Bartlett Development Planning Unit (DPU) as part of the RELIEF Centre Project focusing on prosperity in Lebanon in the context of mass displacement. Therein, we study the effects of real estate policy, and the financialization of housing markets, which have resulted in the eviction and displacement of the most vulnerable social groups in Beirut, and have turned the capital city into an exclusive, unjust, and vulnerable place.

Methodologically, the research develops housing narratives and spatial stories that, situated within larger research, serve as the crossing point between the impact of market-driven urban development on housing rights in Lebanon, and the strategies, opportunities, expectations, and disappointments of elderly women in mitigating evictions, displacement, and the social security of their families. The housing stories and diagrams were originally published by The Housing Monitor, an interactive online platform for consolidating research, building advocacy, and proposing alternatives to advance the right to housing in Lebanon.

Dwelling in Tareek al-Jdeede

Although today’s urban transformations in Tareek al-Jdeede may seem similar to those in most of Beirut’s neighborhoods, the history and socio-spatial make-up of each neighborhood determines a particular set of interactions, strategies of resilience, housing typologies, and vulnerabilities. By 2004, Mazraa—the larger administrative zone containing the neighborhood of Tareek al-Jdeede—contained around thirty percent of Beirut’s tenants living under the old rent law. These tenants—whose contracts were established prior to 1992—are today aged forty-five and above, and landlords have been evicting them or threatening them with eviction at an increasing rate (Public Works Studio, 2015–2017)[1]. Among these, the elderly (and the retired) carry as a social group a set of particularities that places them at odds with state housing policies that rely primarily on the provision of subsidized homeownership loans. They also face the threat of displacement in the absence of social housing programs and with limited social-security benefits. Family connections protect the elderly in some neighborhoods, and the latter attract charity organizations that are often affiliated with sectarian institutions. When it all fails, displacement has severe impacts on their ways of life and on their physical and mental well-being. While relocation generates a number of possible scenarios, we focus on two cases of relocation after eviction: relocation within the neighborhood, and relocation to a distant suburb. Through these case studies, we set out to investigate the ways in which urban processes and property frameworks impact the displacement, and more generally, the housing conditions, of vulnerable social groups, and the urban and architectural forms that housing-related displacement generates.

Um Yumna and Um Hassan Graphic Stories

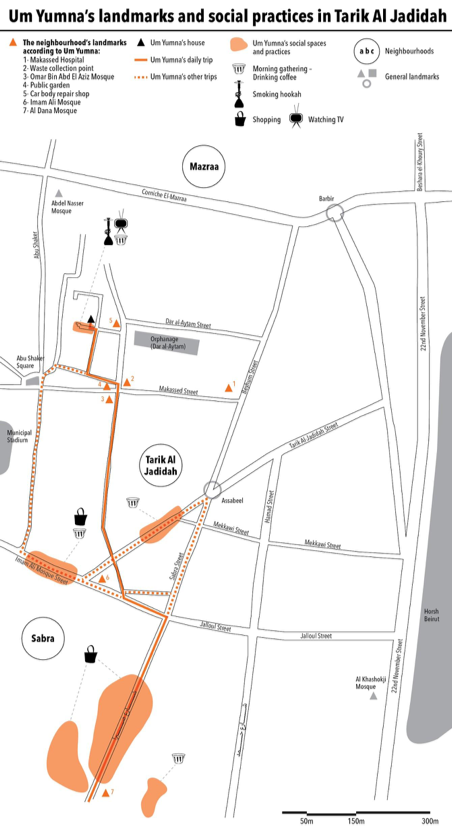

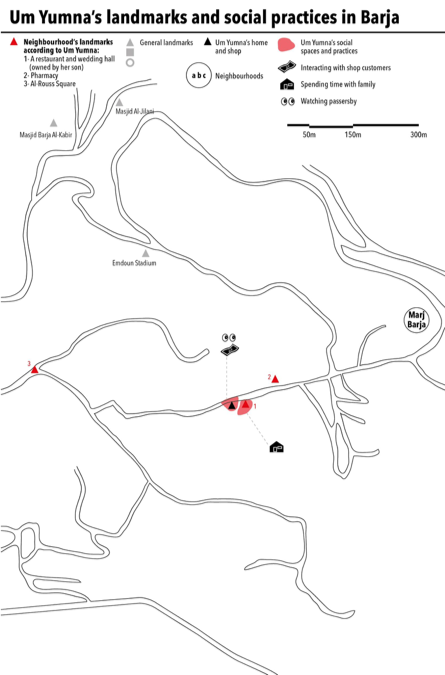

Um Yumna was fourteen years old when she moved from Beqaa to live in Beirut. She had married a young Berjaoui man who worked in the city, and they settled in one of the small homes of Ras al-Nabaa in the mid-fifties. A year or two later, a series of earthquakes shook the country, and Um Yumna’s house in Ras al-Nabaa fell apart. In 1957, the young family moved. At the time, Um Yumna did not intend to spend the next fifty-five years of her life in that little three-room house atop Zreik Hill in Tareek al-Jdeede. In 2012, the owner made a development agreement with an investor to demolish the three-story building and evicted Um Yumna. She then moved to Barja, a town located thirty-five kilometers south of Beirut. This severely ruptured her social relations and daily activities, as they had been intricately rooted in the spaces surrounding her.

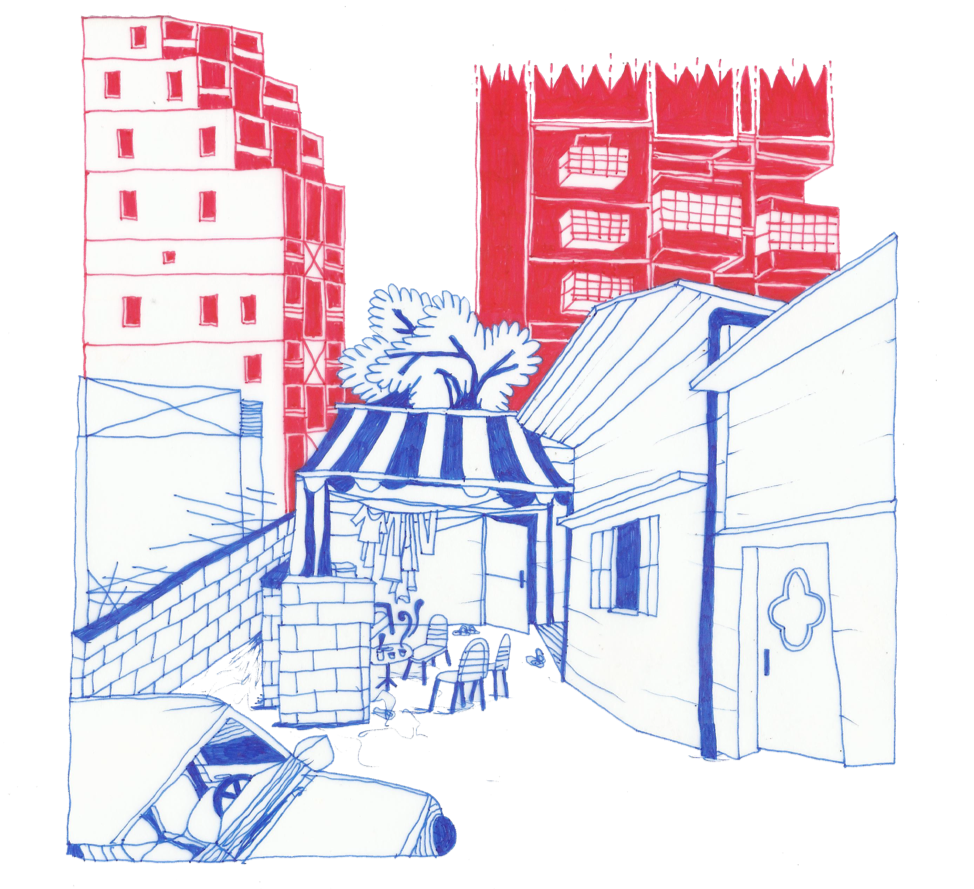

In 1982, Um Hassan, aged eighteen, moved from the neighborhood of Noueiri to Tareek al-Jdeede with her two children. Originally from the south of Lebanon, she married a relative of hers who resided in Beirut. Today, Um Hassan is in her late fifties, and continues to live in the same quarter of Tareek al-Jdeede, but in a different house, after her landlord evicted her from her home of thirty-four years in 2016. A real estate company bought the building in 2011, and Um Hassan agreed to leave. She used the compensation money—in addition to other resources including a loan from a religious institution—to buy the adjacent house. By doing so, she bought into a shared property, which is by itself another form of vulnerability. Between her two dwellings lies a small courtyard where one can find her every afternoon, having coffee and a cigarette. After having lived as an old-rent tenant for decades, buying into a shared property was her only means of resisting displacement.

Um Hassan’s courtyard (1982)

Um Hassan’s courtyard (2019)

The similarities and differences between these two cases allow us to draw a comparative analysis. By looking at the impact of both the process and destination of displacement on evicted elderly and their practices, we can approach the following questions: What means do the elderly have to resist displacement and what role do socio-spatial networks play in this dynamic, especially in the case of Tareek al-Jdeede? Does relocation within the same neighborhood mitigate the negative impacts of eviction on the elderly, and if so, how? How do evictions, displacements, and spatial typologies impact the socio-spatial practices of the elderly, their mobility, and their relation to the neighborhood?

Reflections from the Comparative Analysis

Despite renting for most of their lives, the perception of property ownership as the primary means of achieving socio-economic and housing security prompted both women to seek homeownership after their evictions. They did this by mobilizing a complex web of resources; the capital required to attain homeownership was tightly enmeshed in the relocation options available for these elderly women, and provisions for their children were deciding factors in their decision-making processes.

Nonetheless, the sense of security that homeownership might bring is accompanied by multiple forms of precarity and vulnerabilities. There are no affordable options to buy in the Beirut, where new unaffordable high-rise buildings are replacing the older fabric. As such, the aspiring middle class has mainly sought homeownership in nearby suburbanizing areas, and usually chooses these areas in conformity to sectarian affiliations or origins. In contrast, the working class access substandard housing in the city, usually in areas built before 1992 and threatened by sudden changes brought on by real estate investment or planning implementations. In the meantime, the gap between housing conditions is widening in the city. This takes a heavier toll when developers use the same evicted units to exploit politically and/or economically vulnerable groups, particularly refugees and their families. Developers grant these groups temporary housing in order to generate profit, while retaining the power to evict them spontaneously in order to proceed with building demolition.

Other forms of vulnerability linked to the production of housing in Lebanon manifest in the making of the suburbs. Apart from poor urban planning practices, resulting in environmental and spatial injustices, the arrival of the displaced to these outlying towns sheds light on psychological violence. The elderly endure the crumbling of social networks and support systems, the difficulty of fostering new ones, the reduction of mobility and autonomy, the deterioration of their health, the loss of spatial references, and consequently, the loss of a sense of place and belonging. Concurrently, it was intriguing to observe how the urban morphology—spatial typology or density—can impact the building of social ties. Um Yumna was unable to adapt to her new surroundings in the suburbanizing town of Barja. Sparse urbanization and lack of accessible mobilities led to feelings of alienation, which pushed her to seek a different spatiality for socialization: the grocery store by the side of the road. Um Hassan’s husband echoed this story: he opened a shop in the city, primarily as a means to socialize after developers emptied the neighborhood of its older inhabitants.

The shop as a social interface for the elderly

Through this study, we situate urban evictions beyond the confines of the city, shedding light on an emerging territorial dynamic between inner-city neighborhoods undergoing waves of evictions and radical spatial changes, and the suburbanizing towns that are hosting displaced households. We revisit the myth of homeownership as a secure form of housing in its relation to poor urban planning practices and precarious ownership frameworks. These cases both present narratives that portray housing in the city as an access point to vital economic resources, in a context where developers are commodifying and financializing the urban space in practice and discourse. They also highlight the importance of socio-spatial networks for the elderly—and the urban and suburban processes that threaten them—whereby the understanding of home takes on a larger, more social dimension than that of the physical domestic space.

Urban density as economic resource: Um Hassan’s son and his service business

[1] Public Works Studio, 2015-2017, Mapping Beirut Through its Tenants’ Stories.