Rim Naguib, “The Ideological Deportation of Foreigners and “Local Subjects of Foreign Extraction” in Interwar Egypt,” Arab Studies Journal, Vol. XXVIII, No. 2 (Fall 2020).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this article?

Rim Naguib (RN): At the outset, I was interested in the history of the short-lived Egyptian Communist Party of the early 1920s, which brought together Egyptian and foreign resident workers, artisans, and intellectuals. Looking through the British Foreign Office correspondences about the party and the associated Workers’ Federation, I noticed the frequent occurrence of deportations from interwar Egypt of socialists, communists, and syndicalists, and was surprised by the absence of studies surveying the history of the practice.

Removals by the Egyptian state of “foreign” residents are typically associated with Nasser-era anti-imperialist nationalist policies. But an examination of earlier deportations reveals that the practice has roots in colonial policing, something that has been overlooked by historians. So, I was moved by the desire to tell this little-known history—to survey the role of British colonialism in setting important precedents and instituting deportation based on ideology and ethnic difference in Egyptian state practice.

I was also intrigued by the context in which these deportations occurred. On the one hand, no Egyptian nationality law had been in force until 1929, and the country was home to a substantial population of resident foreigners: subjects of the defunct Ottoman Empire and Russian refugees, alongside other European residents, many of whom had multiple national origins and complex migration trajectories. At the same time, the interwar years were marked by the gradual “Egyptianization” of the state and the economy, following important national milestones such as the writing of the first constitution in 1923, and the victory of the popular Wafd party in the first legislative elections in the country’s history in 1924. In this context, the presence of these foreigners or “local subjects of foreign extraction” (as the British Residency liked to call them) was becoming problematic. Those resident foreigners who espoused internationalist class-based ideologies and pushed the social question to the top of the political agenda were particularly undesirable. Their presence and activities threatened colonial interests as well as those of the local elite, and came to be depicted as inimical to national sovereignty and independence. Their deportation occurred at a defining moment of Egyptian nationalism and nation-state building. On a global level, it was the era of the end of empires and the consolidation of nation states. Many of these foreign residents in Egypt did not have identifiable or traceable national origins, not to mention nationality. Some were rendered stateless and some successfully resisted their deportation.

This is why a study of these deportations, at such a transitional period, can be revealing of the history of the universalization of nation-states and especially of the history of Egyptian nationality and nationalism.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the article address?

RN: The article addresses the colonial practice of ideological-ethnic deportation as an example of the colonial rule of difference. It examines the various mechanisms of legitimation employed by British authorities in Egypt, and the role they played in instituting the practice in Egyptian state laws and policies. The deportations in question were decided and carried out by the British-controlled European Department and its intelligence unit, but in appearance, the Ministry of Interior, like other state institutions, was gradually being Egyptianized by virtue of the 1922 Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence. British officers within the Egyptian state were thus acting behind the guise of an increasingly sovereign Egyptian state.

I argue that this colonial practice contributed in reinforcing Egyptian ethno-nationalism. The article thus also addresses nationalist discourse in the press, its increasing depiction of socialism as a foreign epidemic threatening national sovereignty and security, and the association drawn between the presence and entry of foreigners in Egypt and this threat to the Egyptian social and political order. In a sense, the article looks at the colonial within the anti-colonial, by looking at the colonial legacy within certain manifestations of nationalism.

J: How does this article connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

RN: I have long been preoccupied with nationalism, and the evolution of its discourses and imageries. My previous article, for instance, looks at the roots and functions of today’s highly gendered Egyptian nationalism.

This article on interwar deportations also analyzes nationalist constructions and examines the colonial legacy within anti- and post-colonial nationalist discourse. It departs however from previous work in the way it looks at the specific legal and institutional manifestations of this legacy, by focusing not just on discourse, but on actual legislation that ensued from this colonial practice, such as the anti-socialist amendments of the criminal code in 1931, and the addendum to the Egyptian nationality law in the same year. The article suggests that the selective naturalization of Ottoman subjects, in law and in practice, was partly motivated by the interwar campaign against socialism and socialist foreigners.

J: Who do you hope will read this article, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

RN: I hope this article will be useful to students of colonialism, nationalism, and the Egyptian state. I would like it to illuminate an overlooked aspect of colonial governmentality, and to help question dominant colonialist as well as nationalist narratives. On the one hand, highlighting the role of British colonialism in instituting the practice of ideological-ethnic deportations refutes colonialism's claimed role of protecting foreigners and minorities. On the other hand, the nationalist political elite, in its attempt to establish control over the Egyptian population and to replace the colonial authorities, borrowed the same mechanisms of colonial policing. As soon as the Wafd was democratically elected into government, it cracked down on independent labor organization and syndicalism, and repressed class-based solidarity in favor of conservative ethno-nationalism. Exploring the apparently paradoxical convergence of colonialist and nationalist interests is perhaps politically useful today, and may contribute to a critical approach to dominant nationalist narratives.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

RN: I am now beginning to look at the other side of deportation: at the objects of state removals, and their resistance to displacement. I am interested to know who those were who attempted to prove their Egyptian nationality in the years preceding the inception of the first Egyptian nationality law and following it, and how they went about resisting their exclusion. I am extending this research to the political deportations of 1949 to 1951. By doing so I wish to examine how the state's preoccupation with the policing of revolutionary activities and internationalist solidarity played a key role in selective naturalization, denaturalization, and thus in the definition of national belonging.

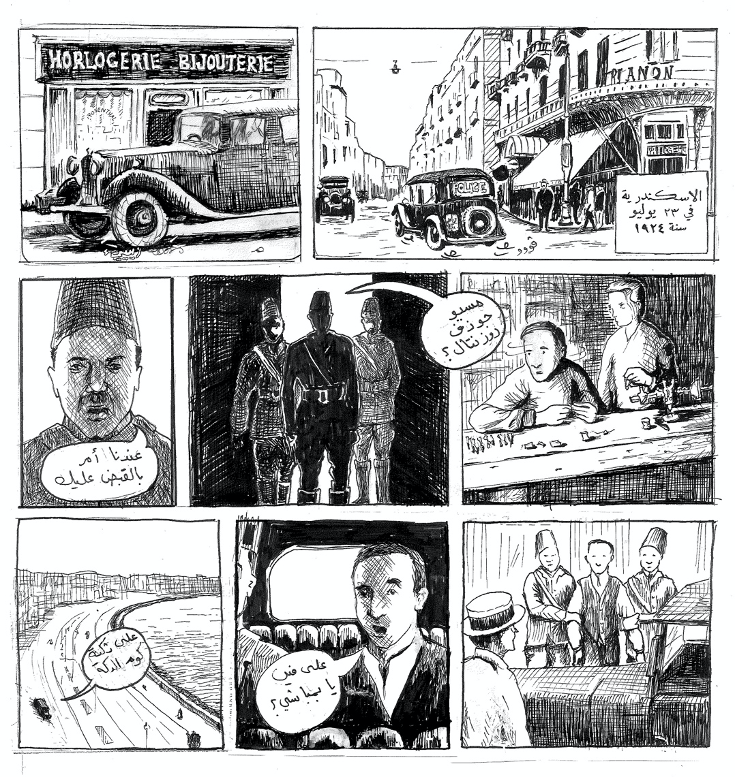

On the other hand, I am working on turning the stories of the deportees, especially those who resisted their deportation, into graphic accounts of my own illustration. In this way, I am hoping to contribute in popularizing this little-known history, and thus in challenging dominant narratives outside academic circles. Below is a page from my graphic interpretation of the deportation of Youssef Rosenthal, a key founder of the Egyptian Communist Party and the confédération générale des travailleurs.

A scene from the author’s graphic interpretation of Youssef Rosenthal’s deportation in 1924.

Excerpt from the article (from pp. 23-25)

On 20 March 1924, al-Ahram reported that preparations were underway “to deport those communists whose involvement in the crimes committed by the accused was not proven. These are known Russians and Syrians.” In their case, deportation was not a verdict based on a specific crime, but a preventive measure, based on their ideology and ethnicity, against the perceived threat they posed. From that point onward, the government arrested and deported many Russians, Palestinian Jews, Greeks, Armenians, and Italians whom it suspected of communist activities or beliefs, notwithstanding their status as local or former Ottoman subjects, and despite their possessing no other nationality documentation.

Although Rosenthal was one of the ESP’s main founders, he had been dismissed from the ECP at the end of 1922 due to internal personal rivalries, and was therefore not among the accused when its leadership was prosecuted. Instead, the parquet summoned Rosenthal as a witness. At court, he answered the parquet’s questions without overtly identifying himself as a communist. Al-Ahram published the full transcript of the interrogation. But two days later, Rosenthal felt compelled to send a personal statement to the newspaper. In the statement, he proclaimed: “I have been and I still am and I will always be, until the last breath, a communist wholly loyal to the cause of the proletariat” and asked for his “share of responsibility,” that is, to be detained and tried along his Egyptian comrades.

A few days later, the parquet summoned Rosenthal again and questioned him over the published statement. Rosenthal confirmed the views he expressed in the letter and was consequently arrested. The Ministry of Interior ordered his deportation from Egypt “because of his communist inclination.” Accompanying Rosenthal on the same cargo ship were two Russian Jews and members of the ECP: Samuel Zaslavsky and Grigorii Schoklender. However, the three of them were prohibited from disembarking at several ports, and al-Ahram continued to follow the whereabouts of Rosenthal under the heading “The Wandering Communist.”

With the Wafd in power and public opinion turned against foreign Bolshevik plots, British officials in Egypt felt no need to legitimate deportations through proof of origin or law infringement. Richard Graves, the acting director general of Public Security, confirmed that Rosenthal’s local subject status “would not legally stand in the way of his deportation.” The Egyptian parquet’s statements also made it clear that requiring proof of crimes for the deportation of foreigners with communist inclinations was redundant.

Back in Alexandria after a month on the ship, Rosenthal endeavored to prove his Egyptian nationality and to seek the protection of the 1923 constitution, arguing that he arrived in Egypt “when traveling from Palestine to Egypt was considered a domestic journey, in one Ottoman homeland.”

Because the government was unable to obtain permission from any country to receive Rosenthal, their plan to deport him failed. But they succeeded in deporting Zaslasky and Schoklender, despite family pleas published in al-Ahram. The parents of Grigorii Schoklender affirmed in their plea that they had moved to Alexandria fifteen years earlier, when their son was only three years old, and that he had become the breadwinner of the family. Neither Schoklender nor Zaslavsky had a Russian passport. British communists aided them in obtaining Russian visas from the Russian embassy in London. After several months in jail, Grigorii Schoklender, his family, and Samuel Zaslavsky were deported to Odessa. Other workers and party members described in al-Ahram as “Russian” or “of Russian origin” were tried in a local court and either jailed or deported.

British officials in Egypt and al-Ahram reporters praised the Wafd government for undertaking the deportation of foreign communists and labor activists. Yet it was British authorities within the Egyptian Ministry of Interior who played a central role in deciding and implementing the deportations. The Unilateral Declaration of Independence reserved British control over four matters, including “the protection of foreign interests in Egypt and the protection of minorities.” To fulfill this task, and after the elimination of the British interior adviser position, the British director general of public security was granted broad authority over the police and even controlled a special intelligence section. Keown-Boyd, director general of the European Department, held this position throughout the fourteen years of its existence from 1923 to 1937. In this period, Keown-Boyd sought to strengthen the European Department in order to maintain a bastion of British control over Egyptian affairs. Thus, despite the creation of a new position for an Egyptian director general of public security during the Egyptianization of the state apparatus in 1922, the British administration retained control over the Egyptian police, and especially the political police.

The European Department led the campaign to suppress socialism and communism in Egypt through heavy recourse to ideological deportation, while concealing British responsibility by working under the guise of Egyptian state sovereignty. A 1929 report on communism by Major Anson of the European Department stated that in the preceding six years, from 1923 to 1929, “eighty-six dangerous communists had been deported from Egypt.”