In the early 2000s, my mother and I regularly frequented the open-air shopping market in Karama, one of Dubai’s oldest and most densely populated neighborhoods. The sensory overload of this downtown neighborhood is emblazoned on my memory: gaudy bags, shoes, and clothes spilled out of shop fronts. Chatter echoed from the concrete balconies of identical modern three-story buildings. Cyclists whizzed by. Bollywood music crackled from portable radio sets. Customers haggled in Hindi, Urdu, and Tagalog. The smell of samosas and leather filled the air. Desi (South Asian) salesmen flanked the door of every shop, rapping “Madam, leather bags, shoes, jeans.”

When I returned to Karama in 2018, I got lost trying to locate this familiar market. Dust from a new interchange had not yet settled. Scaffolding and traffic cones were everywhere. A new tourist destination, the Dubai frame, built and marketed to offer sights of both the historical neighborhoods of “Old Dubai” and the fancy skyscrapers of “New Dubai,” loomed in the distance over an eerily empty neighborhood (Figure 1). Upscale cafés had replaced inexpensive cafeterias. A local landmark, the SANA Fashions building, had disappeared. In its place stood a large crane. Rows of older buildings with chipped paint and exposed brick stood next to walls with bright state-sponsored street art, a mix of decorative and nationalistic symbols in graffiti (Figure 2). Glass panels on new buildings gleamed against adjacent wood accents.

Figure 1: A part of Karama in transition, with ongoing construction, sparsely populated or vacated buildings, and the new Dubai frame visible in the distance. Photo by author.

Figure 2: Sponsored street art in Karama's central open-air market. Photo by Alex Dunham, Time Out Dubai.

You will rarely read about Karama outside local news, but it is historically significant to the city and its immigrants. Located close to the Dubai Creek—a lively trading port that predated the formation of the nation-state in 1971 (Figure 3)—Karama served as an affordable space for Dubai’s South Asian immigrants for over forty years. Close coordination between the city-state and private developers since the early 2000s has accelerated redevelopment efforts there, leading to the rapid transformation of Karama’s landscape, demographic composition, and wider cultural identity. Middle-class South and Southeast Asian residents have been increasingly expelled from this once-affordable space that now caters to the wealthy. Not only has the neighborhood lost much of its middle-class transnational identity, but it is also being erased in the media and from the collective memory of Dubai. The livelihoods and lifestyles of Karama’s former inhabitants are threatened as the space for economic participation diminishes with the establishment of more exclusive, privatized, and upper-class modes of living and leisure in the area.

Figure 3.

Karama’s buildings predate the landmarks that have become synonymous with Dubai. In 1978, before the sail-shaped Burj Al Arab that adorns Dubai’s license plates, and the older but still iconic World Trade Centre, were built, the Dubai government erected Sheikh Rashid Colony in Karama. Sponsored by Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum, this modernist low-rise building complex provided low-cost housing for immigrant workers and their families. The seventeen blocks of this colony (also known as the “7000 buildings” because of its AED 7000 annual rent) had rent pegged at $1,900 a year, which remained stable for years. The low rent and immigrants’ heritable “tenancy rights” encouraged many lower-middle-class immigrant families to set down roots in Dubai, despite having no legal rights to the land (Non-UAE nationals can own property only in demarcated freehold areas, or buy leasehold property [not the land it is built on] for up to 99 years).

In a city where over eighty percent of the population is made up of “temporary guest workers,” Karama is one site where longstanding transnational presence has sedimented in a network of downtown neighborhoods that also includes Bur Dubai, Deira, and Satwa. This is all the more important since migrants to the UAE and other Gulf countries are reliant on precarious residency visas that are tied to their employer and must be renewed every three to four years. Although new long-term residency visas are available to an elite few, there is no clear path to citizenship. Expats in Karama and other downtown neighborhoods are not, and neither do they seek to be, political participants. They exercise their belonging and agency—which may include commentaries on, and critiques of, the state—through economic participation and building communities like Karama. South Asian “bachelors”—men who migrated without family members to work in the Gulf—and families feel at home, small-scale business owners have survived, and skilled workers who may not speak English may still find work (Figure 4). Familiar people, food, languages, and lifestyles in these areas have made Dubai an attractive and accessible place for South and Southeast Asians to migrate to for economic opportunity and community.

Figure 4: Ads for roommates, specifically “bachelors.” Photo by author.

This reality has been rapidly changing with the redevelopment of Karama, which began in 2012 when Sheikh Rashid Colony was demolished to make way for new construction projects. Karama’s proximity, at the edge of the old city and adjacent to New Dubai (visible in Figure 3), affected the perceived rent gap (visible in Figure 3)—the difference between how much the current property earns in rent compared to the rent it can earn once redeveloped. This rent gap became apparent and significant enough in 2014, soon after Dubai won the bid to host Expo2020. There was plenty of vacant land in Dubai, but two factors made building in undeveloped areas less attractive. First, Dubai was hit hard by the 2008 global financial recession. A bulk of real estate projects were put on hold and many were canceled. With the help of its neighbor city, Abu Dhabi, the Dubai real estate market would recover over the next five years. Second, developing new areas on the outskirts of the city was a relatively costly endeavor with a slower return on investment. It involved greater planning, land preparation, and setting up comprehensive infrastructure—inner roads from existing arteries, metro lines, and water and power lines. This financial reality made Karama an attractive site for redevelopment and capital expansion.

Karama’s connectivity to New Dubai was reinforced by the government. In 2016, the Dubai Roads and Transport Authority, a Dubai Government arm, announced a $160 million plan to ease traffic flow specifically to and from Karama, making it better connected to the artery that is Sheikh Zayed Road. The development of two bridges, including an eight-lane underpass and a four-lane flyover, began in 2016 and the bridges were opened in February 2018 (Figure 5). These roadworks and improvements included the widening of inner roads along Karama Shopping Complex. Eviction notices were handed out in sequence to residents of older buildings located along the newly widened roads.

Figure 5: New flyover in Karama, constructed to ease traffic flow. Photo by author.

Catering to wealthy ex-pat families often from the Global North and young Western-educated couples, whose design aesthetics are shaped by Architectural Digest and Pinterest, these projects ultimately increased the neighborhood’s property value. The new buildings—Wasl Hub, Wasl Duet, and Twin Towers (Figure 6)—reflect the experienced ease and connectivity that upper-middle-class city-dwellers enjoy. Amenities facilitating this lifestyle, like many other self-contained gated communities in Dubai, can be found within or near the building: Underground parking for cars, gyms, and pools for fitness and leisure, and grocery chains carrying a larger range of imported products, delivered straight to your home.

Figure 6: Wasl Hub, one of the many new developments in Karama. Photo by author.

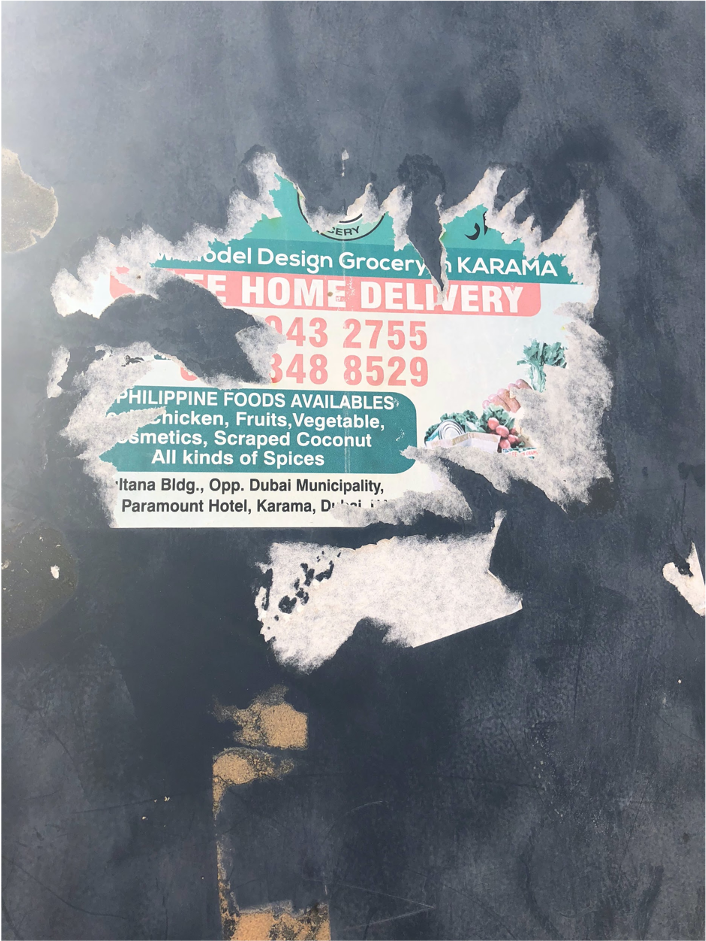

Assumptions about the new dwellers’ languages (English & Arabic) and tastes (upper-middle-class) are built into the space surrounding these buildings. While Karama’s older typing centers—which facilitate the preparation and translation of immigration documents to Arabic—feature signs in Malayalam and Hindi, the new typing center under Wasl Hub advertises itself exclusively in English, assuming the new audience is fluent in English. “Fusion” cuisine restaurants have replaced restaurants serving country-specific cuisine. Chains like Maya Supermarket have replaced previously unbranded, stand-alone groceries. New cafes serve espressos and lattes, replacing cafeterias where coffee had only one form: Nescafe instant coffee loaded with milk and sugar. Stores selling South Asian and Filipino foodstuff and tailors specializing in altering South Asian dresses and shirts (salwar kameez and kurtas) have dwindled (Figures 7, 8, and 9).

Figure 7: Grocery store with Indian foodstuff in Karama. Photo by author.

Figure 8: One of the only remaining tailoring shops specializing in altering kameez and kurtas in Karama. Photo by author.

Figure 9: A sticker near Wasl Hub advertising a grocery store selling Filipino foods. Photo by author.

The everyday, community-driven immigrant residential experience that Karama is known for is being replaced by a more affluent space of “performative living” built around consumer choice. Not only has this led to an ongoing housing crisis for the middle class in Dubai, but slowly, the structures that supported informal and familiar modes of movement and gathering have also begun to disappear. These include “rough” and free parking lots where friends gather, as well as cafeterias where huddling on the sidewalk is the norm. The introduction of tinted glass exteriors on new buildings has altered the quality of the public space outside it. Restaurants with outdoor seating have privatized the sidewalk. Most lots have been paved for paid parking or blocked with tape for upcoming developments. The neighborhood is less walkable than before. These changes have socially disrupted and affectively unsettled the remaining low-income and middle-class population in Karama.

Redevelopment, Aligned with Brand Dubai

In the 1990s, Karama looked like the rest of Dubai. Beige modern buildings had popcorn-textured walls. Box air-conditioning units hung out. Rough parking lots where residents socialized were a common sight (Figure 10). In the early 2000s, this changed. The older creek neighborhoods became less important in the development narrative of Dubai, skewing in favor of spectacular developments by star architects in newer parts of the city. In its quest to be recognized as a global city, Dubai incorporated elements of established cities like New York and London into the New Dubai landscape. Decision-makers emphasized luxury and consumerism: tall glass skyscrapers, man-made water features, large shopping malls, five-star hotels, entertainment venues, gated communities with central air conditioners, built-in gas supply, and underground and over-ground paid parking spaces. This became the poster for New Dubai, a geographical area encompassing almost everything south of Dubai World Trade Centre.

Figure 10: Older modern buildings with box A/Cs, balconies and rough parking lots in Karama. Photo by author.

In less than two decades, Dubai’s center shifted as its identity also changed. Through tourism advertisements, media images, and narratives of wealth, prosperity, and consumer freedom,state-aligned actors and businesses curated an image of Dubai with two components that were productive for capital: “modern” (read luxurious, convenient, and consumable) and “traditional” (read Emirati and Arab). Solidified and packaged for marketing on the global stage, Dubai positioned itself as the ideal place to live, work, and visit for the world’s upwardly mobile, wealthy, and resourceful, skewed towards citizens of the Global North with already-powerful passports. Redevelopment priorities, delineated by public and private forces, informed Brand Dubai.

Like the neighborhoods of Bur Dubai, Deira, and Satwa, Karama was only featured in the Brand Dubai media narrative through glimpses of old souks and dhows, with its residential, non-consumable, and transnational components rendered largely invisible. Karama’s absence and relative insignificance to the larger narrative, which is productive for capital, minimized resistance to and provided justification for accelerated redevelopment. Redevelopment in Karama has been followed by projects in Deira (Deira Enrichment Project), Marsa Al Seef on Deira Creek, and the extended Dubai Creek (Jewel of the Creek).

Raced, Classed, and Gendered Expulsions

The inflation in post-redevelopment rent was astonishingly high: rent in new buildings in Karama was forty-two percent higher than in older buildings, the remaining of which are slated for demolition.[16] While older buildings charged between $8,200 and $10,500 annually, new buildings cost $19,000 to $25,000 for one and two-bedroom apartments. The new rents rest comfortably at the very top of the middle-class range of salaries in Dubai. Others within this class do not earn enough to cover this new rent. Salaries for middle-class employees have not seen any significant raises in the last five years either. This impacts South and Southeast Asians in Dubai more, since they often earn less than their Western or Arab counterparts because compensation packages are designed to reflect “salary expectations based on country of origin.” This nationality-based hierarchy among low-income and middle-class workers is well-documented, where Asians are paid up to twenty percent lower than Arab nationals, and forty percent lower than white US/European nationals for the same job and without generous schooling and travel packages. Most also do not have the privilege of employer-sponsored accommodation and have to pay rent out of their salaries.

The redevelopment and attendant gentrification of Karama, therefore, impact South and Southeast Asians disproportionately. Many have been forced to leave the neighborhood, city, and often country, exacerbated by the layoffs following COVID-19. These raced expulsions are also gendered, as the accelerated changes in Karama affect women’s quality of life drastically. Middle-class South Asians in Karama live in close quarters, often share languages, values, and cultural understanding. They even shop at the same stores. Being embedded in a familiar community allows South Asian women greater mobility and agency. I saw this firsthand with my mother, who fearlessly navigated through and bargained in Karama market with salespeople in Hindi yet did not feel the same sense of comfort interacting with salespeople at shopping malls. Community affords women greater freedom in some areas, since neighbors may share responsibility for the children. Daycare facilities are difficult to find in Dubai and hiring a nanny is expensive. Karama, in its density, also provided a critical social network that significantly increased the resources and knowledge (about the UAE and their home countries) available to women in these communities.

The story of Karama points to an accelerating trend of writing over the unspectacular in the UAE, uprooting residents who have put down roots, and wiping away sediments of the long history of exchange, movement, and settlement between the Gulf and South Asia. If current trends persist, a richer, more transient, Western, and whiter middle class will replace Dubai’s current residents in the next few decades, reflecting the city’s new relationship with the world.

Since a strong middle class has gained ground in the Global South, the shrinking of affordable space in Dubai, the Middle Eastern “American Dream,” will be felt keenly. It will be locally disenfranchised populations of South Asia who will be most affected (Christians and Muslims, religious minorities in India, for example, are more likely to migrate out). South Asian and Southeast Asian expatriates are already at a disadvantage in the global immigration hierarchy. They have limited mobility due to their passport ranks. Trends in the Global North (particularly, the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe) of tightening borders, growing nationalism, and the nationalization of jobs, with quotas for South Asian immigrants, will also mean fewer immigration opportunities for these groups.