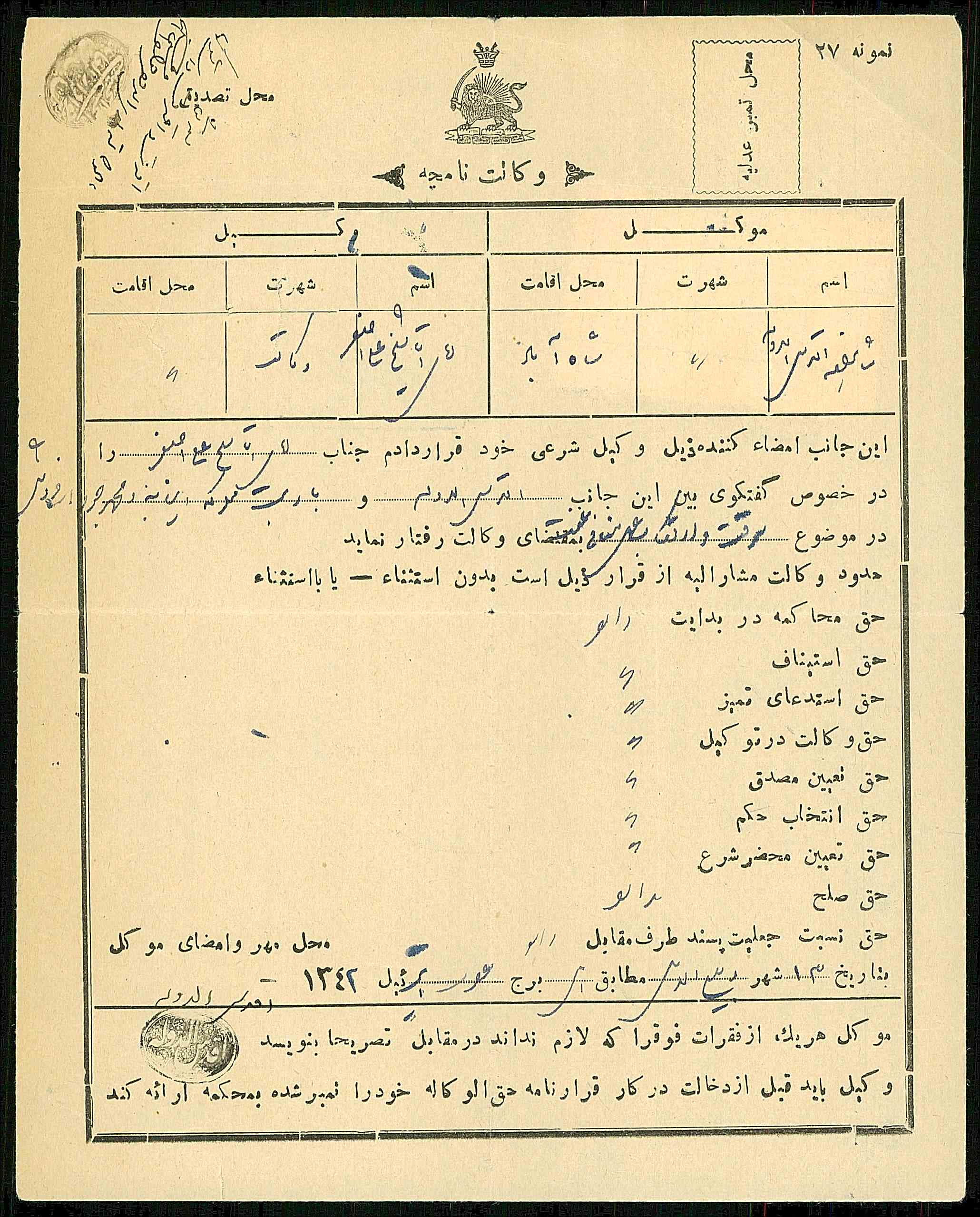

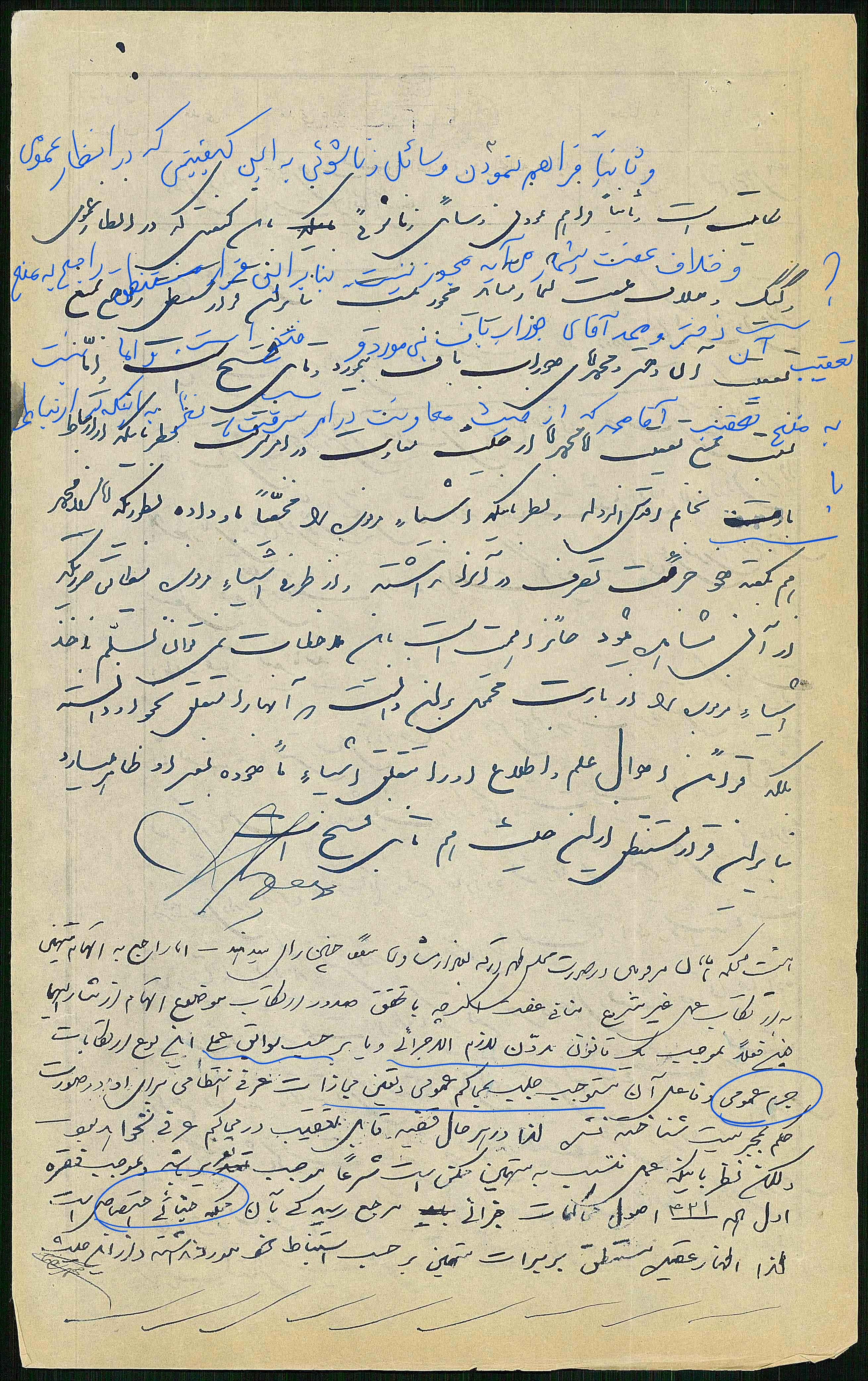

The idea for this piece emerged from an archival riddle. In 2016, in search of archives that would give me (Jairan) access to the voices and lived worlds of sex workers in 20th century Iran, I turned to the legal archives stored in the National Archive of Iran. To my surprise, most of the cases that were tagged with the keyword “prostitution” did not actually involve prostitutes. In broadening the scope of the search through different keywords, I came across a sizeable number of court documents and police reports that were labeled with the term “sex-related crimes,” (جرائم جنسی). Curiously, despite being described in the archive catalog as “sex-related crimes,” some of the cases, at least at the outset, did not seem to contain any sexually charged references or disputes. To add to the puzzle, there is no corresponding category of crime with the same title in any version of Iran’s penal code. What, then, constitutes a “sex-related crime”?

The slippage between what we expected and what the archives exhibited suggests a gap between the legal consciousness and the grammar of crime for the contemporary archivist and that of the original early 20th-century world of the actual court documents. How can today’s researchers use these gaps analytically to write a history of sex and sexuality from the margins of legitimacy? To answer, we reviewed roughly 30 court cases, which featured crimes such as robbery, family and neighborhood disputes, adultery, fornication, rape, prostitution, procuring/pimping, sex with minors, sodomy, and acts of public indecency.

This piece centers the constructed archival category of “sex-related crimes” to raise questions about the processes of the production of archives – in particular legal archives – and what a critical approach to archives can offer scholars. Legal archives are under-explored yet extremely rich sources that offer insight into the lifeworlds of marginal subjects, who exist at the threshold of the legitimate space of citizenship. Following Michel-Rolph Touillot’s call to attend to the processes of the production of history – to moments of creating, assembling, and retrieving historical facts – we investigate the legal consciousness of courtrooms as well as that of the archives. Which subjects and experiences do legal archives make possible and visible, and which ones do they erode? This piece further argues that legal archives provide rich historical data that facilitate historiography from below, specifically to uncover how lay and ordinary people navigated the law.

A Brief History of Legal Archives in Iran

Legal archives in their current form did not exist prior to the post-Constitutional Revolution period (1905-1911) and the emergence of the practice of archive keeping in state institutions.[1] Some earlier court proceedings can be found in the daily reports that provincial governors (wali) submitted to the royal court.[2] However, these proceedings tend to be one-liners with minimal description of the case and final ruling. Following the centralization of trial procedures, the separation of legislative, executive, and judicial bodies, and the bureaucratization of the judiciary in the immediate aftermath of the Constitutional Revolution, the ministry of the judiciary began to keep its records, particularly the full records of court cases that were disputed in courts of appeal. As such, historians have unprecedented access to the space of the courtroom, interrogation sessions, statements of defendants, and the reasoning behind the judges’ rulings in the post-Constitutional era. The physical documents, however, are not immediately available to researchers. Rather, they are categorized, tagged, and taxonomized by archive catalogers. A historiographer then only has access to historical facts that have already been sorted through particular language and keywords. What is the politics behind labeling, categorizing, and tagging court documents? What does this process conceal and what does it reveal?

Fact Assembling as Silencing

Today the Iranian National Archive has a large digital platform and a search engine through which we can search for cataloged documents online.[3] The last time I (Jairan) spoke to one of the catalogers of the center, she mentioned that there are millions of documents that have not yet been sorted. The process is slow and painstaking, and not as systematic as one would think. Who decides which carton to open, which collection to attend to, and which keywords to apply is a complicated process that requires engaging with the history of cataloging in Iran as well as digital humanities theories and processes, both of which are beyond the scope of this brief essay. For our purpose, which is primarily to introduce readers to these legal archives, we focus on the keywords, labels, and descriptors of documents through which the search engine works.

In what we refer to as “In vivo” labeling,[4] the catalog mirrors the terminology of the actual court documents and as such reproduces the grammar of the courtroom of the time. For instance, many documents are described with the term “unchaste and dishonorable acts,” (بیعفتی و بیناموسی). This term in fact matches the title of a category of crime under the first penal code presented in 1916 by Nusrat al-Dawlah to the third parliament as “the customary penal law” (قانون جزای عرفی). “Lustfulness” (شهوترانی), attempts to persuade, deceive, incite, or encourage women and girls into lustful acts, forced intercourse, sex with minors, prostitution, and “other acts against chastity” were criminalized under this section of the code. The 1925 version of the penal code further added zina and sodomy to this section. Although the code was never officially legislated due to the annulment of the third parliament, it was put into practice until 1925. Since the term “acts of indecency” belong to the legal language of the 1910s, such labeling practices take us directly to the legal consciousness of the time, which tells us something about the legal grammar of “indecency,” and its intersection with the everyday lives of citizens.

What counted as “public indecency” in the 1910s? How did defendants narrativize their acts so as to avoid conviction? Who were the targets of this law? For one example, this specific keyword took us to a court case titled “crime and the act of public indecency” in the online catalog. The case includes two Armenian men and one woman (of unknown religious affiliation) who were arrested in an alley.[5] The case includes an eyewitness statement claiming that what he witnessed was not “in accordance with Islam nor with any creed and tradition of human assembly.” The ruling of the court, which includes a series of convictions and pardons, raises fruitful questions for us about the role of religious sensibilities, and their relation to shame and decency, particularly in settings that were considered public.

Documents are not merely tagged and titled using this method. Often, the archivist enters keywords for court cases not according to the laws from the time of the creation of legal documents, but according to their own contemporary sense of legality and criminality. The same document, for instance, is tagged with the following terms “Christians,” “investigations,” “rape,” “infidelity,” and “harassment.” While the title of the case echoes the vocabulary of the court documents, these tags demonstrate a rather different strategy of cataloging. Here, the cataloger has created alliances between crimes that are otherwise absent from the legal grammar of the 1910s. For instance, the cataloger has translated “crimes of public indecency” to “harassment laws” and as such recast the incident with a completely different narrative. We suggest that we can use this slippage of language critically, interrogating the gap between “harassment” and “public indecency,” as well as the two different conceptions of harm that each implies. Why would the cataloger deem this incident harassment? Could this reading be related to the contingency of living in contemporary Tehran, where women find themselves being drawn into public spaces on the one hand (for necessities of life), while on the other hand enjoying very little safety in those spaces?

To give another example, in 1931, the case of Yadullah was brought to the court of misdemeanors on the charge of committing sodomy (لواط) forcefully with the 11-year old Ghulam-Husssain.[6] The ministry of justice that was responsible for the initial record keeping of the case referred to the file as a case of “unchastity,” (بیعفتی), which mirrors the language of the penal code of the 1930s. Curiously, however, the National Archives cataloger has labeled the file as “prostitution.” To add more layers to the multiple legal grammars present in this case, in the physical documents of the court, the defendant (the 30-year old man) is prosecuted not for rape but “sodomy” (لواط). These three different terms — rape, sodomy, and unchastity — tell us something about the conflation of rape with other forms of illicit sex that are not defined based on the question of consent. We suggest that these constructed affiliations allow us to interrogate our own contemporary conceptions of rape, unchastity, prostitution, and sodomy. What moral world does each conceptual lexicon open up and what different forms of legal foreclosure do they suggest? Who is the ideal victim of each crime category?

We further want to draw attention to a mode of cataloging that at once entails a non-juridical but still legal-moral adjudication. Legal consciousness is not simply bound by the space of the court but rather, continuously spills out of the courtroom and into the consciousness of lay people (including the contemporary cataloger.) In these cases, the vocabulary that the cataloger employs to label the court case implicitly contains a legal judgment, ingraining defendants and sometimes mistaking the historical claimants as criminals.

Let us elaborate through another example. Searching the keyword “prostitution,” the online catalogue lead us to the case of Mujaver Bani Sa’d.[7] In November 1978, Mojaver pleaded that Ali Firuz Taj had seduced his [former] 23-year old wife, Nusrat Dailami Hamdani, who ran away with Ali to another city, abandoning the claimant and their five kids behind. Mujaver presented a photo of Nusrat and Ali as proof of their “illegitimate” (na-mashru’) relationship. At the outset, this seems to be a case of fornication rather than prostitution. The main reference to prostitution in the court documents — including the judge’s decision, the investigator’s statement, as well as interrogation minutes — can be found in Ali Firuz Taj’s statement where he accuses Nusrat of being a prostitute and her husband of being a procuror. Most probably, he was hoping to exonerate himself from the crime by accusing the other defendant. The court investigator eventually decided on an order of nonsuit, based on lack of any evidence as well as a prior dismissal of the case in another court branch. This means that the ex-husband had tried to convict his ex-wife previously in another local court to no avail. Yet because the cataloger tagged the case with the keyword “prostitution,” Nusrat is retroactively framed in the archives as a prostitute. For a historian of urban prostitution, the archive recasts Nusrat as a subject of study. As such the archive cataloger echoes the voice of the male defendant rather than the female, subtly guiding the historian to her name, signifying prostitution. Labeling the archive, then, becomes a legal decision made outside of the legal sphere. Thus, we see how a particular gendered legal consciousness conceals legal and historical nuance, imposing itself across the time-space of the courtroom.

The Subject of/in History

Available legal documents from this period — including interrogation sessions, defendant’s statements, witness testimonies, and court reasonings — demonstrate how law created its subjects, brought them into the legible space of the courtroom while at once silencing particular kinds of statements and narrations of the self. Let us explain through another example. In 1924 a man named Yadullah was brought to court for having performed “unchaste” acts (بیعصمتی) with an eleven-year-old boy named Ghulam-Hussain. According to the court report, Yadullah was accused of having tied Ghulam-Hussain’s hands, stripping him, and raping him while threatening him with a knife. However, the case had no direct witnesses. The case was brought to the court by a public prosecutor, probably tipped off by the mother of the victim, who persistently followed the court decisions and eventually filed for an appeal.

The penal code of the time required private claimants for crimes such as rape or illicit sex unless they were committed in public. The council of judges did not consider the meadow where the crime had taken place a public venue. As such, they deemed the crime private. As a result, there was a need for a private claimant for the case to have legal standing. Being underaged and fatherless, Ghulam-Hussain did not have a rightful guardian in the eyes of the law. His mother, who was following the case in search of justice for the harm done to her son, was not considered Ghulam-Hussain’s lawful guardian, since the law only accounted for male guardianship. As such, the courtroom concealed the harm done to Ghulam-Hussain and with it erased the possibility of addressing that harm through the state apparatus. In the 1920s the law only acknowledged assault insofar as the victim was defined within the bounds of the state’s patriarchal definition of kinship within the nuclear family construct. Harm towards individuals outside of these patriarchal definitions was rendered invisible. The mother’s claim was further disarticulated due to the specific grammar of legal claims and legal subjects. This case demonstrates how the immediate space of the courtroom itself suppresses the articulation of certain affective bonds and familial structures (such as guardianship) that reside in a space beyond that of positive law.

Court archives can also tell us something about how ordinary people translate and transplant their lives into and through the law. In 1932, Aghdas al-Dawlah, the lady of a household, brought her servant to court for having taken a lover, claiming that this indecent behavior had “damaged” the reputation and honor of the household.[8] Aghdas emphasized that since the servant — now 24 years old — grew up in their household from the age of four, she should be counted as a member of their family, and as such, her chastity equaled the chastity of the family. Aghdas drew on her own conception of kinship, which differed drastically from the official legal conception of family based on blood. Her claims, however, had no legal standing since the law did not consider the lady of the house as the servant’s legal guardian. Aghdas’ lawyer then had to come up with yet another claim: robbery. They accused the servant and the lover of stealing silver candleholders. An ironic twist: if the servant is like kin, then how could she have stolen from her own house? This discrepancy is beside the point. Our intention is not to discuss the process of adjudication, but rather show how law-conscious subjects (mis)perform their subjectivity in front of the court. In reading these legal archives we should ask: which experiences are eroded and which ones are made visible in this legal lifeworld?

These two cases, we propose, demonstrate how the courtroom makes certain claims unstatable and certain kinship ties incomprehensible before the law, while nonetheless creating the possibility for both defendants and claimants to narrate themselves and their actions through the language of law. What traces of the non-legal world of the subjects of courts are left in these documents, if any? Where are the mis-performances in court? Can one trace a parallel space (however minimal) of a non-legal world, in courtrooms, or does law necessarily disarticulate other forms of life – that is if we agree that not all life is legal life?

Conclusion

Archives make and unmake their subjects. They sign the ordinary person into the political language of the modern state. Archives further reveal subjects of juridical, medical, welfare, and military institutions to the scholar. We are suggesting a new direction in the historiography of Iran that adopts an anthropological approach towards history and its subjects. In the past decade or so, historians have been trying to write against early 20th-century statist historiographies of modern Iran.[9] This piece is an invitation to further investigate archival epistemologies through the prism of legal archives. We believe that law, as the cornerstone of the modern state, is a particularly generative site from which to interrogate how subjects are signed into the state as citizens, and what forms of life are suppressed or sidelined in this process. Police reports, petitions, court cases, legislations, parliament committee’s minutes, are all sources that remain almost untouched by historians of modern Iran. These archives open a whole new legal lifeworld to the scholar. As the historical anthropologist Ann Stoler reminds us, archives produce an epistemology.[10] It is in attending to these epistemologies that we can tap into the changing mentality-reality of state institutions, and their deep entanglement with the everyday lives of Iranians.

[2] The absence of such court proceedings does not automatically mean that in Iran prior to the Constitutional period, records of courts were not kept systematically. Rather, as Wael Hallaq notes in his survey of legal archives within the Muslim world, it is highly possible that local judges and qadis kept these records in their personal archives. Since courts were not institutionalized during the Qajar era, the records were kept in private collections that are lost to us. For a comprehensive discussion on legal records see Hallaq, Wael. “The ‘Qāḍī’s Dīwān (Sijill)’ before the Ottomans.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 61, no. 3 (1998): 415–36.

[3] You can find the catalogue at the following website: http://www.nlai.ir/.

[4] “In vivo” labeling refers to codes that emerge from the exact words or phrases in the documents such as participants’ interview transcripts.

[5] “Residigi bi jenayat va ‘amal-e munafi-yi ‘iffat az su-yi du nafar masihi,” 1920 (AH 1299), 298/99726, National Library and Archives of Iran.

[6] “Parvandeh-ha-ye shikayat dar mavarid-i: khiyanat dar amanat, sirqat, va fahsha,” 1931 (AH 1310), 298/4774, National Library and Archives of Iran.

[7] “Residigi-yi qaza’i bi ittiham-i khud-furushi va rabita-yi namashru’-i zani dar Abadan,” 1978 (AH 1357), 298/28931, National Library and Archives of Iran.

[8] “Parvanda-ha-yi dadgustari dar murid-i fahsha va ‘amal-e na-mashru’,” 1949 (AH 1327), 298/6571, National Library and Archives of Iran.

[9] Cyrus Schayegh, “Seeing Like a State: An Essay on the Historiography of Modern Iran,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 1 (2010): 37–61.

[10] Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).