Léopold Lambert, États d’urgence: Une histoire spatiale du continuum colonial français (States of Emergency: A Spatial History of the French Colonial Continuum) (Éditions Premiers Matins de Novembre (PMN), 2021).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Léopold Lambert (LL): After the 13 November 2015 attacks in Paris, we in France and people in most overseas colonies entered into a regime that not only saw fully armed police officers and soldiers patrolling the streets, but also that facilitated over 5,000 police searches of Muslim homes, offices, restaurants, and mosques, as well as over 750 arbitrary house arrests of Muslim people between 2015 and 2017. This regime felt less like an exceptional measure than an exacerbation of the structural violence we have witnessed for years. I remembered the state of emergency being applied against the banlieue uprising of 2005, when I was still a nineteen-year-old student who had recently moved to Paris. It was also relatively well known that the state of emergency was initiated to (unsuccessfully) crush the Algerian Revolution between 1954 and 1962. There were too few bridges between these three eras being made. This was even more true in relation to two lesser known (in France) applications of this legislation: in 1985 against the Kanak insurrection of 1984-1988 in Kanaky (i.e. the indigenous name of colonial New Caledonia) and in 1987 against the strike of Tahitian dockers who blocked the supplying of the French military nuclear bombing center in Mururoa.

Creating bridges between these different moments was crucial for me, and I wanted to do it in a way that would be useful for the people involved in these political struggles. This is why it took me five years to do the research and write the book. In the context of France, where I wrote it, the part about Kanaky was particularly fundamental for me, since the Kanak political imaginary remains profoundly unknown in France, even in the anti-colonial movement. It is definitely not this book that will change this into depth, but I am hoping that it will humbly contribute to making a few dates, a few organizations, a few political figures and, most importantly, a fragment of the Kanak political cosmology enter our imaginary over here, at the core of the colonial empire.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

LL: The book is essentially a historical description of three space-time: the Algerian Revolution, the Kanak insurrection of the 1980s, and the banlieues’ political organizing and revolts from the 1970s to today, particularly since 2005. As the book’s title indicates, I describe these three uprisings through spatial history. This means that I examine how space and the built environment are modified by them and how, in turn, they influence them. Often, architecture is weaponized in order to serve counter-revolutionary purposes: camps, prisons, colonies, massive modernist residential buildings, police stations, and so on. However, although the neighborhoods of colonized people, such as Algiers or Constantine’s casbahs, the Algerian shantytowns of the Paris banlieue, or the Kanak villages are always existing under the threat of police or military raids, their spatiality is instrumental in the way it can provide the conditions of a tenable asymmetrical warfare.

Through the detailed account of these three space-time (to which we can add Tahiti in 1987), I tried to define the concept of a French colonial continuum. This is far from a new concept, and a good number of activists in France use it but, often, it is used exclusively in a temporal dimension, and I thought that it was important to talk about the spatial one as well. This is how the book also mobilizes Viet Nam, West Africa, Guadeloupe, Comoros, Reunion, Guyane, and other colonial geographies at different moments of their histories under French colonial domination. It also looks at how people navigate in this colonial continuum: colonized people, immigrant and undocumented workers, as well as exiles of course, but also the cogs of the empire: militaries, public servants, and politicians. I mapped the careers of a couple of dozens of them; they moved from one colony to another, acquiring counter-revolutionary skills and using them in their next destination which, sometimes is a prefecture with many banlieues in France.

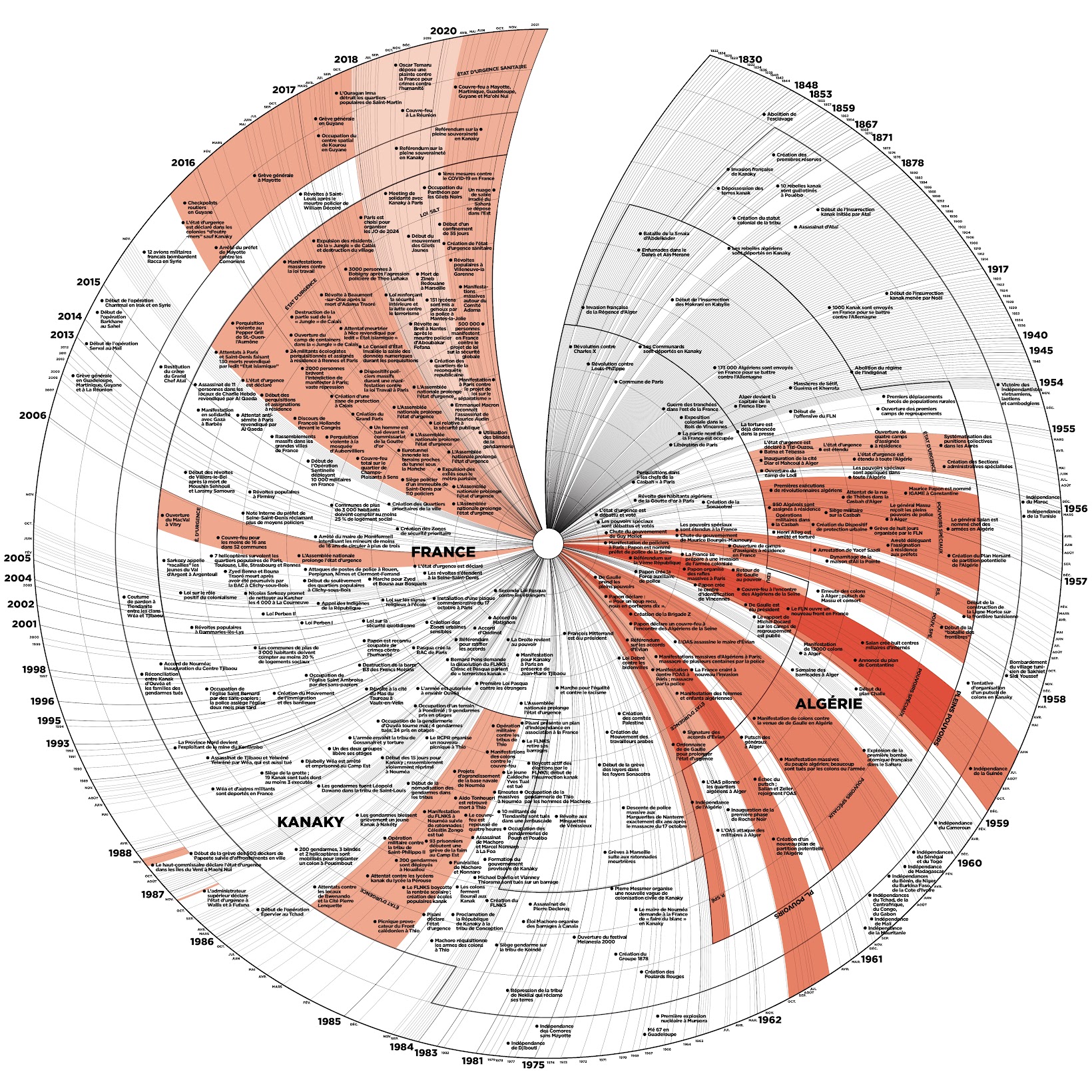

This map is part of several I made for the book to try to associate the text with more graphic documents. There are a certain number of photographs I took in France, Algeria, and Kanaky, but also some maps and a diagram that attempts to show the entire space-time of the book. It is not so easy to read but I believe that if one really dives into it, they can see how all the moments and geographies shown on it are somehow connected.

Image caption: Chronocartography of the space-time examined in the book États d'urgence: Une histoire spatiale du continuum colonial français by Léopold Lambert

As for the literature, my research led me to three kinds of sources in addition to the many encounters with people—whether here in France, in Algeria, and even more poignantly in Kanaky. The first one was books that have been written on tangential subjects. In this regard, the works of Mathieu Rigouste, Samia Henni, Mogniss H. Abdallah, and Hassina Mechai have been absolutely instrumental, and I am very grateful to them for our conversations.

The second type of source was newspapers from the different eras mobilized by the book. What I like the most about those is that sometimes an incredibly potent quote or detail would be found somewhere in the corner of a page, something that often the journalist probably did not even perceive as crucial. The other thing I find very interesting about newspapers is how they allow one to see the planetary context of each moment one is looking at. For instance, I had never realized that the colonial French officers’ 1961 putsch in Algiers happened when the world was still looking at Cuba and the failed US invasion of the Bay of Pigs. Some connections were more expected such as the concomitance of the last few months of the Kanak insurrection and the beginning of the Palestinian First Intifada…

The third kind of source was the activist publications. The Algerian National Liberation Front’s journal El Moudjahid and the Algerian National Movement’s La Voix du Peuple are references in this matter, but so should be the Kanak publications of Bwenando, L’Avenir Calédonien, or Kanak Immigré. Those bring the embodiment of the struggles in a much more acute way than any French journalist would ever be able to describe.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

LL: I am trained as an architect and my work has always consisted of trying to show how space (whether we think of the built environment or geography at large) is instrumental in the enforcement of regimes of domination, in particular that of settler colonialism in Palestine. This book is the least architectural I wrote, and I had to consider the question of time as seriously as the question of space for it but, as its title suggests, the spatial dimension of the French colonial continuum remains crucial.

My work as the editor-in-chief of The Funambulist also consists of cultivating internationalist solidarity between political struggles in the world. The bridges that the book attempts to build between these three space-time are made in the same spirit.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

LL: This is a very important question as, for me, this book can only exist if it is somehow useful to the political struggles with which it stands in solidarity. In the context of the Kanak struggle, this means contributing to the re-activation of forms of solidarity between Kanaky and activists in France. In the context of the antiracist movement in France, it can try to tie the struggle to others, and also show the spatial dimension of what we are up against.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

LL: I am the editor-in-chief of The Funambulist, which has been my full time job even during these five years of writing this book. I am continuing to edit a new issue every other month around “the politics of space and bodies.” In terms of writing, I have wanted for a while to write a political analysis of a very simple architectural object we take for granted: the key. So, I might try to work on this in relation to settler colonialism, carceralism, and private property in the future.

Excerpt from the book (from the Introduction)

Nous sommes le 16 mars 1871 à Bordj Bou Arreridj en Kabylie. Le cheikh El Mokrani et 6 000 soldats se lancent contre l’administration coloniale de la ville. Plus tard, ils seront près de 200 000 à mener l’attaque contre l’occupant français à Tizi-Ouzou, Larbaâ Nath Irathen (Fort-National), Dra-el-Mizan, Dellys, Béjaïa (Bougie) en Grande Kabylie. Quarante ans après l’invasion française de la Régence d’Alger et vingt-quatre ans depuis la capitulation de l’émir Abdelkader, c’est le début de la grande rébellion des Mokrani et de la confrérie soufie Rahmaniyya contre l’ordre colonial en Algérie. Quarante-huit heures plus tard, le 18 mars 1871, alors que le siège de l’armée prussienne sur Paris s’est achevé quelques semaines auparavant, les soldats du 88e régiment d’infanterie refusent d’obéir à l’ordre de tirer sur la foule, en particulier sur les nombreuses femmes venues les empêcher de récupérer les canons de la Garde nationale sur la colline de Montmartre. Leur mutinerie et fraternisation avec la population parisienne initie la Commune de Paris, prolétaire, socialiste et internationaliste – elle compte notamment de nombreux Italiens et Polonais, mais aussi un petit nombre d’Algériens. Après quelques courts mois de succès de ces révoltes, les répressions contre-révolutionnaires menées par Adolphe Thiers sont d’une immense violence. En Algérie, des milliers d’insurgés kabyles sont exécutés sommairement et des amendes imposées à leurs tribus forcent ces dernières à des décennies de pauvreté – leurs terres sont également mises sous séquestre. À Paris, la semaine sanglante (21-28 mai 1871) voit les troupes versaillaises reprendre Paris en tuant plusieurs dizaines de milliers de communards. Les dizaines de milliers de prisonniers kabyles, dont Boumezrag El Mokrani, le frère du cheikh, et communards – dont Louise Michel – sont jugés sommairement et envoyés au bagne colonial. Les condamnations lisibles sur les procès verbaux des jugements sont, quasi-identiques des deux côtés de la Méditerranée : « l’excitation à la guerre civile », « le pillage », « l’incendie », « la participation à l’insurrection » sont autant de chefs d’accusation que nous retrouvons indistinctement à l’encontre des insurgés kabyles ou communards. Certains de ces condamnés sont déportés vers la Guyane, tandis qu’une majorité est envoyée dans la colonie pénale appelée Nouvelle-Calédonie par les Européens. Là-bas, colonisés maghrébins et prolétaires européens se rencontrent sur la terre d’un troisième peuple, ou plutôt des nombreux autres peuples autochtones de la Grande Terre et des îles l’entourant. Il s’agit de celles et ceux qui, rassemblés politiquement des années plus tard, revendiqueront le nom de Kanak.

Le 25 juin 1878, une troisième révolte débute : celle de 3 000 Kanak de différentes tribus unifiées par le grand chef Ataï. Ils prennent d’assaut le village de La Foa sur la Grande Terre et libèrent un chef de clan emprisonné dans une gendarmerie française. L’administration coloniale est dépassée par cette révolte qui ébranle vingt-cinq ans d’occupation française dont une quinzaine d’années de bagne colonial. Elle propose des remises de peines aux bagnards qui acceptent de participer à la contre-révolution. Ils sont nombreux, y compris parmi les communards et les Kabyles, à accepter ce faux dilemme. Parmi les Parisiens, Louise Michel et Charles Malato se distinguent en prenant fait et cause pour la lutte anticoloniale des Kanak. Près d’un siècle plus tard, les deux organisations révolutionnaires kanak Foulards rouges et Groupe 1878 rendront compte de cette solidarité : les premiers dans leur nom même qui rappelle les foulards rouges offerts par l’institutrice anarchiste à des camarades kanak et les deuxièmes en rendant hommage à la Commune de Paris dans un texte intitulé « Il était une fois une grande ville ». Au cours de la contre-révolution coloniale, la négociation contrainte avec l’occupant n’est cependant pas l’apanage des déportés communards et kabyles. Certaines chefferies kanak, elles aussi, se voient offrir des marchés par l’administration coloniale.

Ainsi, le 1er septembre 1878, Ataï est assassiné et décapité par l’un des membres d’une des tribus de Canala. Quelques mois plus tard, à l’issue de cette guerre asymétrique, les bagnards kabyles et communards sont amnistiés, l’administration coloniale leur donne des terres à cultiver mais leur interdit de quitter l’archipel. Le colonialisme de peuplement se construit ainsi : le bagnard devient soldat colonial puis exploitant de la terre autochtone spoliée. Conscient du vol de la terre qu’il prétend désormais être la sienne, le colon se force à demeurer milicien dans l’âme, comme nous le verrons à de multiples reprises dans cet ouvrage.

Cette histoire est autant une histoire des violences coloniales qu’elle est une histoire des révoltes à leur encontre. Il s’agit avant tout de rencontres : certaines délibérées, d’autres fortuites ; certaines violentes, d’autres solidaires. Ce qui les lie en premier lieu est bien-sûr la machine contre-révolutionnaire française, mais les résistances organisées face à celle-ci la transcendent et forment entre elles des solidarités fondatrices d’autres futurs.

Cette « rencontre » entre différents groupes révolutionnaires et/ou anticoloniaux peut servir d’exemple autant que de prologue de ce que j’appelle le continuum colonial français que je tâcherai d’expliquer plus longuement dans cette introduction. Le rapprochement des territoires d’Algérie, de Kanaky et de France m’intéresse particulièrement dans le cadre de ce livre. En effet, des années plus tard, ces trois géographies deviendront les trois principaux sites d’application d’une loi française contre-révolutionnaire : l’état d’urgence. La violence policière, militaire et judiciaire qu’une telle législation permet est déployée huit fois entre le moment de sa création et le 1er novembre 2017. À cette date, la loi SILT, dite « renforçant la sécurité intérieure et la lutte contre le terrorisme » initiée par Emmanuel Macron entre en vigueur et rend quasiment obsolètes les mesures permises par l’état d’urgence puisque cristallisant la majorité d’entre elles dans le droit commun.

[...]

Comparer n’est pas équivaloir

Les différents territoires au sein desquels l’état d’urgence est appliqué depuis sa création, offrent un panel de géographies liées de manière plus ou moins directe au colonialisme français. La première, l’Algérie, constitue le paradigme de la colonie de peuplement française. De même, sa Révolution incarne, avec celle d’Haïti 150 ans plus tôt, le paradigme du mouvement de libération anticoloniale. La deuxième géographie en question, Kanaky, bien que souvent associé aux autres territoires appelés « outre-mer » malgré des situations géographiques et historiques radicalement différentes, partage de nombreuses caractéristiques avec la situation algérienne, en particulier son statut de colonie de peuplement. La troisième enfin, plus diffuse, ce sont les quartiers populaires de France. La comparaison avec les deux premières peut sembler ici délicate. Comme me l’a rappelé le politiste kanak Pierre Wélépa lorsque je comparais maladroitement les luttes de la jeunesse de la tribu de Saint-Louis en périphérie de Nouméa avec celle des quartiers populaires en France : « Il n’y a pas beaucoup de similitudes entre ce qui se passe chez les colonisateurs dans leurs quartiers et la lutte d’un peuple autochtone. » Bien que cette affirmation puisse sembler de prime abord quelque peu excessive, il est crucial d’observer que l’exercice de comparaison est toujours périlleux. En effet, il a tendance à s’affranchir des spécificités liées aux contextes, aux peuples, aux histoires, aux combats et, en cela, les réduit à une compréhension simpliste.

En d’autres termes, cet exercice bien souvent essentialise les différentes nations colonisées et groupes racialisés, ainsi que leurs luttes respectives dans un grand groupe des « colonisés » ou des « racisés » en effaçant les particularités de chacun. Dans le cadre de ce livre, l’exercice comparatif qui en motive l’écriture est une comparaison entre des modes opératoires et une instrumentalisation de l’espace par la puissance coloniale dans différentes géographies à différents moments historiques. Cette comparaison, je le crois, se justifie précisément par le fait que le respect de la spécificité des lieux et des moments n’est pas particulièrement le fort de la gestion coloniale. Ainsi, les comparaisons entre formes de résistance à cette puissance coloniale ne sont que très peu nombreuses, sauf lorsque les groupes de résistance se revendiquent eux-mêmes d’un combat passé. À cet égard, la Révolution algérienne fait figure de référence.

La comparaison entre des espaces-temps proprement coloniaux comme l’Algérie des années 1950 ou Kanaky des années 1980 avec celui des quartiers populaires en France dans les années 2000 et 2010, bien que délicate, se justifie pour trois raisons a minima. La première, limpide, est qu’une majorité des habitants des quartiers populaires portent en eux la mémoire, les traumatismes, et les histoires personnelles et collectives de la domination coloniale – française pour la plupart, mais également britannique, belge, espagnole, italienne et portugaise. La deuxième est que le rapport de l’État français à ces populations (que ces dernières possèdent la nationalité française ou non), notamment dans les interactions avec sa police, se manifeste dans une généalogie claire d’une époque explicitement coloniale. La troisième raison est que la spatialité des quartiers populaires constitue un enjeu crucial partagée entre contrôle étatique et appropriation communautaire par les habitants eux-mêmes. Bien que cet enjeu ne soit pas du même ordre que la libération d’une terre sous domination coloniale comme dans le cas de l’Algérie et de Kanaky, ces combats font apparaître des similitudes non-négligeables. Ces trois aspects permettent d’inscrire l’espace et l’histoire des quartiers populaires ces soixante dernières années au sein du continuum colonial français, comme je le ferai tout au long de cet ouvrage.