Andrew Simon, Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt (Stanford University Press, 2022).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Andrew Simon (AS): The book’s origins may be traced back to the onset of the Egyptian Revolution eleven years ago. Shortly after graduating from college in 2010, I flew from North Carolina to Cairo for a fellowship at the Center for Arabic Study Abroad. It was during mass demonstrations in the days leading up to Hosni Mubarak’s downfall that I first realized the power of sound. In Tahrir Square, where I was taking classes at the time, I witnessed people from all walks of life express their discontent with the present and their dreams for the future. I listened to poets criticizing corruption, protestors chanting in unison, and Egyptians breathing new life into old songs. Following the fellowship’s conclusion, I returned to the United States for graduate school, eager to dive deeper into Egypt’s acoustic culture. I wrote papers on everyone from Shaykh Imam to Shaaban Abdel Rahim and at the center of these endeavors was a one common thread: audiocassettes. Returning to Egypt, I set out to write a history of the cassette that became a history of a country through the window of its cassette culture. Reading popular periodicals, across multiple decades, occasioned this shift. When making my way through weekly Egyptian magazines, such as Ruz al-Yusuf Akhir Saʿa, I encountered cassettes in a number of unexpected contexts, including advertisements for the “modern home,” popular crime reports praising the security sector, and letters to the editors censuring the perceived “pollution” of public taste. Collectively, these surprising items inspired me to consider what the social life of one everyday technology “in action” might teach us about the making of a modern nation. Media of the Masses explores what happens when the audiocassette travels well beyond the walls of its workshop in Europe.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

AS: In Media of the Masses, I explore how audiocassette technology empowered an unprecedented number of people to create culture, circulate information, and challenge ruling regimes long before the internet entered our daily lives. The book operates as a mixtape, with each track, or chapter, revolving around a particular theme, from consumption, the law, and taste to circulation, history, and archives. In each section, I place cassettes, cassette players, and their diverse users into direct conversation with broader historical developments taking place in Egypt’s recent past. Everyone from smugglers and singers to politicians and police officers play a part in this story, which strives to advance a series of conversations in Middle East studies.

First, in scrutinizing the lifecycle of sounds, from their production and preservation to their materiality and meaning, the book makes a case for multi-sensory scholarship and captures how people in the past (much like we do now) relied upon multiple faculties to apprehend the world around them. The result is a more embodied history that reveals the complexity of people’s sensory worlds. Two key dimensions of these worlds are mass media and pop culture. On these fronts, the book reorients prevailing treatments of only the most recent mass media and state-sanctioned voices by elucidating the impact of an earlier technology and introducing individuals who were popular but not praised by local gatekeepers. In doing so, it calls into question the “newness” of new media, like the internet, and encourages us to revisit the lives and legacies of those who challenged ruling regimes and ended up on the margins of national narratives as a result.

Second, Media of the Masses expands the methodological horizons of Middle East scholarship by inviting us to think more critically about archives and the sorts of stories they impede or make possible. In the process of navigating Egypt’s “shadow archive,” a constellation of audio, visual, and textual sources that exist outside of the Egyptian National Archives, the book contemplates how we may write a history of a nation without its national archives and shows how one might democratize historical research at a point in time when local authorities are all too eager to monopolize the past in the present.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

AS: Nearly a decade in the making, Media of the Masses is my first book and the outcome of my longstanding interest in media, popular culture, and the Middle East. One of the book’s chapters on Egypt’s “vulgar soundscape” was the basis for an article in the International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, while other parts of the story closely resonate with my teaching, including a class on “Soundscapes of the Middle East,” which considers how the study of sound can enrich our understanding of the world around us.

For songs from artists mentioned in Media of the Masses, check out this Spotify playlist.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

AS: Media of the Masses is a book for anyone interested in music, media, or the Middle East. It draws upon not only my fieldwork in Egypt, but also conversations with students in the United States. Based on these classroom exchanges, I believe that this story will resonate with undergraduates as well as graduate students and will generate no shortage of discussion in courses on popular culture, mass media, the history of technology, and the Middle East. In addition to inviting students to revisit what they know about the Middle East, how they know it, and why the region’s history matters, the book, I hope, will appeal to scholars, especially those working across disciplinary boundaries. InMedia of the Masses, I strive to break new ground in the field of Middle East studies, in particular, by advancing a still nascent “acoustic turn,” centering the archive as an avenue of inquiry, and demonstrating how popular culture may radically deepen our understanding of the past as opposed to merely complementing what we already know.

At the same time, I wrote this book with a wider community of readers in mind, including individuals who might be familiar with cassettes but less so with Egypt’s recent past, or who may wish to know more about media in the Middle East beyond social media and the Arab Spring. A mentor of mine once told me that there are two types of authors: those who write about complex things in a simple manner and those who write about simple things in a complex manner. He encouraged me to always fall into the former camp and this is something I consciously tried to accomplish in this book when sharing the story of an ordinary technology’s extraordinary impact. Whether or not I succeeded on this front will be up to readers to decide.

Lastly, Media of the Masses is the book I wished to find on the shelves of Cairo’s Sur al-Ezbekiya paper market and it is one I now want to share with audiences across the Middle East. It has long been a dream of mine to have the book translated into Arabic and I am very grateful for the project’s coverage, so far, in media outlets in and outside of Egypt. Going forward, I welcome any opportunities to discuss the book with those who pick up a copy of it.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

AS: At the moment, I am working on a few different projects. Later this year, I will be making my private collection of cassettes public in a digital archive, where scholars, students, and anyone interested in music, media, or the Middle East will be able to access, explore, and enjoy a wide range of recordings. Drawing inspiration from Syrian Cassette Archives, Gharamophone, and other pioneering initiatives, this platform will feature everyone from pop artists to popular preachers and everything from amateur mixtapes to professional productions that provide a thought-provoking window onto the past.

Additionally, I am completing two articles inspired by my work for Media of the Masses. The first piece considers what record culture might teach us about British colonialism, while the second presents a cultural history of family planning in Egypt.

There is then the matter of a second book project. I am writing a biography of Shaykh Imam, whose life and afterlife raise key questions concerning national narratives, the politics of popular culture, and the Middle East.

I will be posting updates on all these projects on Twitter @simongandrew, where my DMs are open. In the event anyone would like to share Shaykh Imam stories, I’m all ears!

J: What surprised you the most about your exploration of Egypt’s cassette culture?

AS: The parallels between the past and present. One example that immediately comes to mind is Mahraganat music, which gained popular traction over the past decade and has inspired no shortage of criticism from Egyptian cultural gatekeepers, who regularly accuse its artists of “polluting” public taste. This accusation, I discovered during my research, is by no means new. In fact, it may be traced back to at least the 1970s and 1980s, when critics condemned performers of another genre, shaʿbi music, for “poisoning” public taste through cassettes that circulated with ease outside of state-controlled channels of cultural production. When unpacking these earlier charges of “vulgarity” one thing that became clear was a struggle over Egyptian culture and who has the right to create it, a conflict that continues to play out today.

Excerpt from the book (from Chapter Three, pp. 95-100)

In 1978, an Egyptian student by the name of Siyanat Hamdi wrote a doctoral dissertation on the decline of Egyptian music. To evaluate the dissertation, Hamdi’s university invited external musicians to lead its review. Among the artists asked to discuss the findings was Muhammad ʿAbd al-Wahhab, who, if he read it, would have likely enjoyed the lengthy tome, which included an entire chapter on his mastery of Arabic. The scope of Hamdi’s project was panoramic in nature, covering singing in Egypt from its inception to the present day. Part and parcel of this history were “vulgar” songs, such as Ahmad ʿAdawiya’s “Everything on Everything” (“Kullu ʿala Kullu”), and what permitted such “inferior” numbers to spread and the “weak” voices behind them to become well known. In an article covering the student’s research in Ruz al-Yusuf, one writer asked readers how Egyptians could “escape from ʿAdawiya’s school” prior to directing them to Hamdi’s work. If ʿAbd al-Halim was “the nightingale,” and Umm Kulthum was “the voice of Egypt,” ʿAdawiya was nothing more than “noise” that Hamdi, the reporter, and many other commentators could do without.

Few figures in Egypt’s modern history are more synonymous with “vulgar cassettes” than Ahmad ʿAdawiya, one of the pioneers of shaʿbi music, a contentious genre regularly disparaged by critics. Born Ahmad Muhammad Mursi on 26 June 1945, ʿAdawiya grew up listening to al-Atrash, ʿAbd al-Wahhab, and ʿAbd al-Halim. Little is known about his early life, but according to one account, ʿAdawiya’s father traded livestock for a living and relocated his family to Cairo when the entertainer was still an adolescent. It was in Egypt’s capital where a young ʿAdawiya, began to pursue music seriously. Unlike some of his peers, who enrolled in prestigious conservatories to perfect their skills, he honed his craft on Muhammad ʿAli Street, a historic avenue renowned for its musicians. There, he played both the nay (reed flute) and the riqq (tambourine) with a musical troupe and followed in the footsteps of several other artists who learned how to become performers on the street. Fame and fortune, however, would have to wait until he met Sharifa Fadil, a singer and actress of some acclaim, who facilitated his introduction to Maʾmun al-Shinawi, a leading lyricist. In 1973, ʿAdawiya recorded his first major hit, “al-Sah al-Dah Ambu,” on a cassette for Sawt al-Hubb, where al-Shinawi served as an artistic adviser. The tape was an unprecedented success, selling an estimated million copies. The first of many hits that ʿAdawiya would release on cassettes, the recording transformed him into a household name and placed him at the center of debates on audiotapes and the “death” of taste.

From the beginning of his career, ʿAdawiya attracted the ire of critics. Respected musicians ridiculed him and those belonging to his “backward” generation. Muhammad ʿAbd al-Mutalab, a pioneer of the “popular song,” attacked ʿAdawiya on multiple occasions. When asked about the quality of songs in the mid-1970s, a time when ʿAdawiya and audiotapes were gaining momentum, he once responded bitterly, “They are machinations! A cheap trade whose manufacturers try to outdo one another in proving their ability and their superiority in corrupting the taste of the next generation.” Other artists, meanwhile, denounced ʿAdawiya outside of the press. In one incident, Muharram Fuʾad entered a casino known for playing ʿAdawiya’s tapes in Alexandria and, upon hearing his numbers, demanded that “foreign music” be broadcast instead. The building’s owner proceeded to play one of Fuʾad’s songs and, when it did not please those present, forced him to leave the premises. There is then the case of ʿAbd al-Hamid Kishk, a popular preacher who slammed ʿAdawiya in one of his sermons. According to Kishk, ʿAdawiya’s “al-Sah al-Dah Ambu” was as “tasteless” as it was “meaningless.” Distancing himself from the singer’s “vulgar” tracks and his use of colloquial Arabic, the shaykh implored Egyptian youth in classical Arabic to study high poetry. Combined with attacks on ʿAdawiya as a foul side effect of Egypt’s defeat in the 1967 war and Sadat’s economic opening that reportedly empowered the “culturally illiterate,” all of these commentaries cast the singer, his success, and his cassettes in a resolutely negative light.

Not all Egyptian public figures, however, embraced a black-and-white view when it came to the cassette star. Naguib Mahfouz was among those who adopted a more nuanced stance. At times, the Nobel laureate criticized ʿAdawiya’s music for its “triviality” and “crudeness,” two qualities, he claimed, that resulted in his productions being the “furthest thing from elegance,” but in other moments the author recognized his “strong, sorrow-infused voice” and recalled several of ʿAdawiya’s songs with ease, only to wish their lyrics were more meaningful. ʿAbd al-Wahhab, similarly, did not despise ʿAdawiya, but he did insist that his music would lose its resonance. In an interview with Akhir Saʿa in 1976, he stated that ʿAdawiya’s popularity was of little concern to him “because in every country in the world there are all sorts of artistic colors and forms.” What bothered ʿAbd al-Wahhab at the time in Egypt was not ʿAdawiya’s presence but the absence of “noble beautiful art,” which, he believed, was “what remains in the end.” Unlike the permanence enjoyed by refined music, ʿAdawiya’s songs, he implied, were a passing phenomenon. Despite the reportedly “fleeting” and “crass” nature of ʿAdawiya’s tracks, some of Egypt’s leading artists nevertheless gravitated toward him. Among these figures was none other than ʿAbd al-Wahhab.

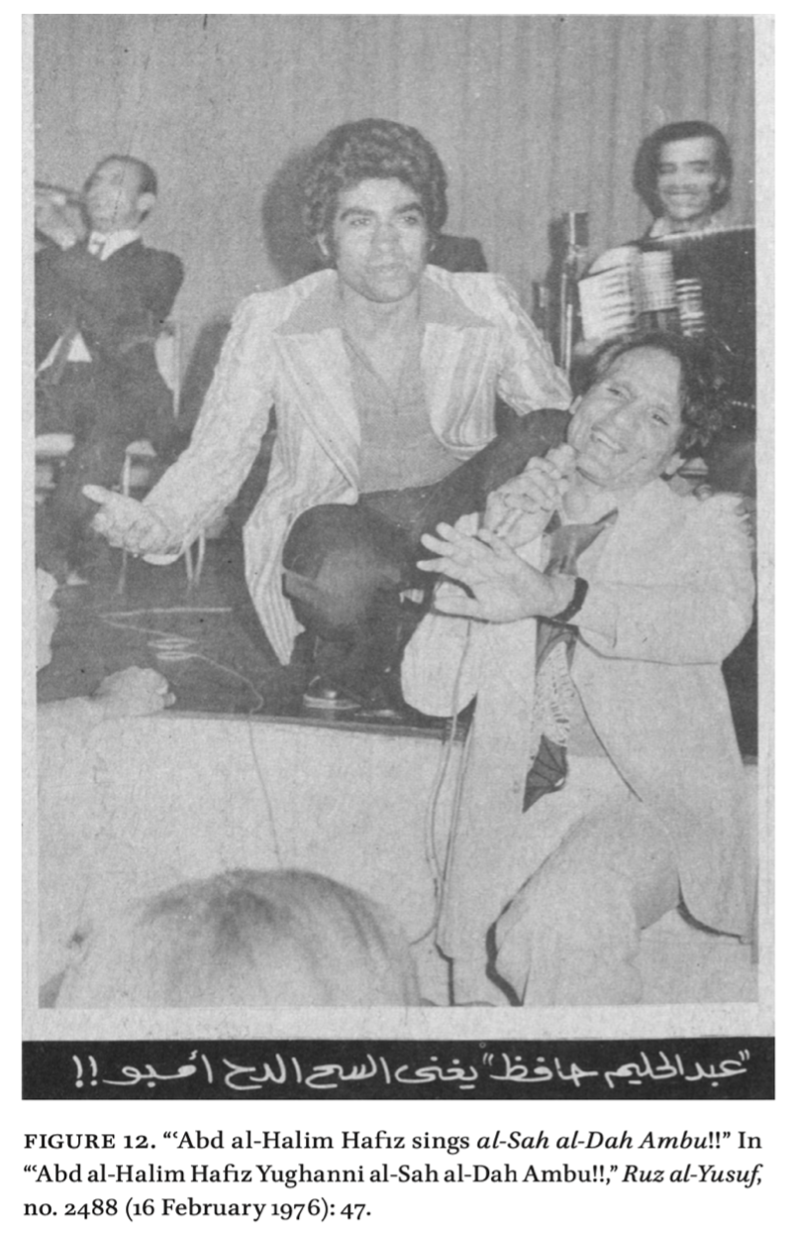

The same year ʿAbd al-Wahhab refrained from castigating ʿAdawiya in Akhir Saʿa, he tried to poach the entertainer as the co-owner of Sawt al-Fann, a major recording label. ʿAbd al-Wahhab’s partner, ʿAbd al-Halim, approached ʿAdawiya in London, where he was performing at the Omar Khayyam Hotel. There, he offered ʿAdawiya a five-year recording deal. Shortly thereafter, ʿAdawiya’s label, eager to retain him, countered ʿAbd al-Halim’s terms by raising its star’s salary to E£500 per song in addition to a cut of the price of his recordings. Less than two weeks after news of Sawt al-Fann’s proposal broke, Ruz al-Yusuf printed a picture of ʿAbd al-Halim gleefully singing “al-Sah al-Dah Ambu” alongside ʿAdawiya at a party. The photo caused a stir (fig. 12). Arabic periodicals reprinted it and writers claimed the scene evidenced ʿAbd al-Halim’s approval of ʿAdawiya’s “vulgar” art. In response to this charge, ʿAbd al-Halim reportedly denied the incident ever took place. Whereas the Sawt al-Fann kingpins may have preferred to keep their dealings with ʿAdawiya out of the public eye, other artists did not mind supporting the singer in a more open manner. ʿAdawiya’s tapes, after all, were wildly popular.

Throughout ʿAdawiya’s career, some of the biggest names in Egyptian music wrote compositions for him, a reality that undermines any clear-cut division drawn by critics between “cassette stars” and “esteemed artists.” In the 1970s, Mahmud al-Sharif, Muhammad al-Mugi, Kamal al-Tawil, Munir Murad, and Sayyid Mikkawi, all worked with the shaʿbi sensation. Egyptian lyricists, likewise, were well aware of ʿAdawiya’s selling power. One need only consider how one writer penned a song for Muharram Fuʾad only to give the same text to ʿAdawiya before Fuʾad could perform it because any tape ʿAdawiya released sold “40,000 copies.” Even Egyptian celebrities who did not work directly with ʿAdawiya appreciated his music. The actor, writer, and singer Isʿad Yunis stated that his songs neither could nor should be censored. Not only was it “impossible to pull a sorry tape from a taxi to put a Beethoven tape in its place,” she claimed; songs like ʿAdawiya’s provided a useful brain break for scholars and others who could not be expected to tune into artists like French Pianist Richard Clayderman “around the clock.” At the same time, commentators did not accept every defense of ʿAdawiya. When ʿAdil Imam, an Egyptian actor who appeared in multiple films critics found to be “vulgar,” claimed that local intellectuals did not approve of ʿAdawiya’s songs because they were “withdrawn from the people,” one reporter sharply reprimanded him. Being one with the people, the writer rebuked, “does not mean smoking hookah or swaying to the melody of ‘Get Well Soon Umm Hassan,’” one of ʿAdawiya’s popular tracks. Regardless of the divergent opinions that Egyptians expressed toward ʿAdawiya, there was one thing everyone agreed on: audiocassettes were integral to his career.

Throughout the mid- to late twentieth century, Egyptians encountered ʿAdawiya’s tapes in several different settings, from cafés to taxis to hair salons. As one writer observed early on, ʿAdawiya’s voice emerged from “Cairo’s side streets and alleyways to take the ears of the middle class by storm and to impose its songs upon it by way of cassette tapes for no apparent reason!” Notably, one place where ʿAdawiya’s tracks did not resonate was state-controlled radio. Contrary to the claims of some scholars, ʿAdawiya and other up-and-coming artists did not simply turn to cassettes in the 1970s “as a practical solution for low-cost distribution and promotion.” Although the affordability of both processes was a plus, ʿAdawiya and his peers harnessed audiotapes, first and foremost, because Egyptian radio refused to broadcast what its officials deemed “vulgar” material. Forced to find another way to be heard, ʿAdawiya used tapes as a tool to reach a mass audience and to make his name known outside of weddings and Cairo’s backstreets. In overcoming the radio’s ban by way of tapes, ʿAdawiya confirmed what one writer called “the success of the illegitimate” and contributed to the perceived demise of taste.