[This article is part of a series produced from the undergraduate student workshop, centered on Bhar Lazreg, and held at the National School of Architecture and Urbanism (ENAU) in Tunis. To read the parts of this series, visit the introductory article by Shreya Parikh here.]

« Moi, j’habite ici depuis une vingtaine d’années » nous dit Mohamed, habitant de Bhar Lazreg, lors de notre première rencontre. Il continue en prenant le soin de préciser : « mais je suis originaire de La Marsa. » Il était important de préciser qu’il venait de la partie “noble” de la commune. Intrigué, il nous pose ensuite la question : « Pourquoi vous travaillez sur un tel quartier ? Qu’est-ce qui peut bien vous y intéresser ? ». Nous étions précisément du côté de la commune qui n’était pas supposé intéresser deux étudiantes en architecture.

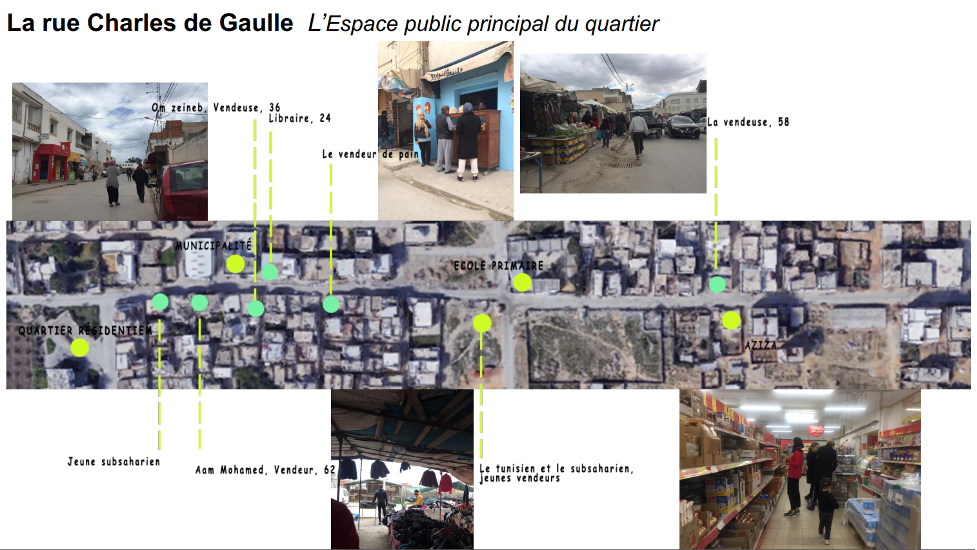

Image 1 : Rue Charles de Gaulle, l’espace public principal de Bhar Lazreg

Nous sommes dans la banlieue Nord de Tunis, dans la commune de La Marsa, connue pour sa plage, son boulevard, ses quartiers chics, ses cafés et ses vendeurs de glace. Au-delà de cette image touristique, il y a pourtant des quartiers populaires à La Marsa. Beaucoup moins connus, ils restent dans l’ombre, malgré l’importance de leur superficie et du nombre de leurs habitants.

Notre première visite sur le terrain à Bhar Lazreg était notre première visite dans ce quartier ; nous n'y étions jamais allés auparavant ! La rue Charles de Gaulle qui est l’artère principale de Bhar Lazreg était animée par la dynamique qu’imposait la présence des nombreux commerces et cafés populaires bondés d’hommes. Cette voie principale nous semblait trop étroite pour tout ce qui s’y passait. Les trottoirs étaient occupés par les commerçants formels et informels, par les tables des cafés, par les poubelles. Tout ceci créait des obstacles pour les piétons.

Etant donné que nous avons vu le chaos partout autour de nous, nous nous sommes demandées si les gens d'ici ont un sens de la houma - un sentiment d'appartenance au quartier. L’une de nos premières observations concernait la présence de multiples commerces de proximité (hanout en arabe). Nous nous sommes donc intéressées à cette composante essentielle du quotidien des habitants pour mieux comprendre la vie de quartier et le sentiment de houma , donc nous avons échangé avec quelques commerçants et leurs clients.. Nous avons changé les noms de toutes les personnes que nous avons interrogées pour ce texte afin de protéger leur identité.

Am Mohamed

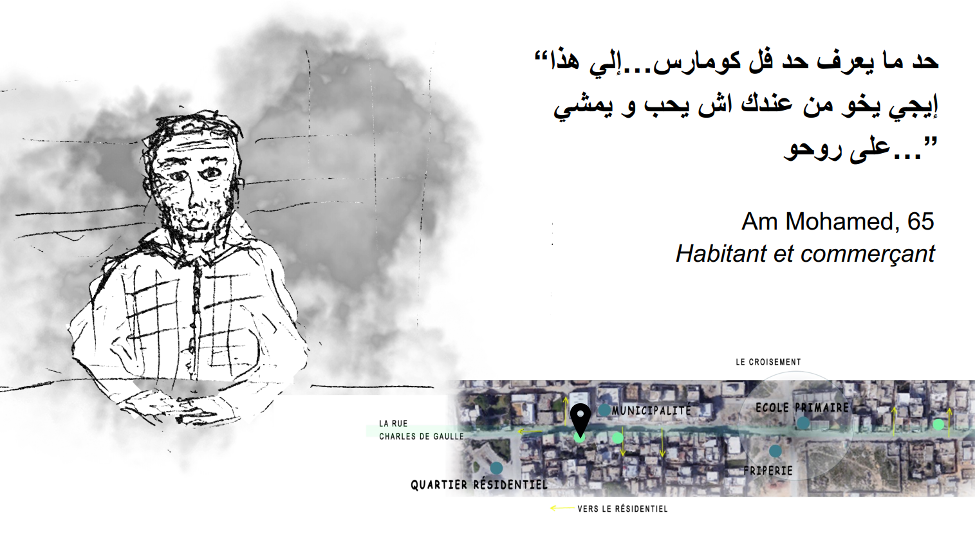

Image 2 : Am Mohamed – « en commerce, personne ne connaît personne… chacun vient acheter ce qu’il veut et puis il repart »

Au premier jour du mois de Ramadan, un samedi matin, nous avons été dans l’épicerie de Am Mohamed, un homme d’une soixantaine d’années. En entrant, on le distinguait à peine ; tête baissée, il était au fond de sa boutique, lisant le Coran qu’il tenait entre ses mains.

En entendant notre “bonjour,” il a levé sa tête vers nous, et nous a salué en retour avec un air surpris. Nous lui avons demandé si nous pouvions lui poser quelques questions par rapport au quartier. Il a répondu avec des mots à peine audibles « par rapport à quoi... quelles questions ? ». Nous lui avons demandé si les gens se connaissaient bien ici. Il a hésité puis nous a affirmé, avec un léger sourire, qu’en commerce personne ne connaît personne, que chacun venait acheter ce qu’il voulait et repartait.

C’est alors qu’un client est entré et a interrompu notre conversation. Il voulait acheter du pain. Il s’est adressé au commerçant en l’appelant « Am Mohamed », utilisant son prénom précédé d’un Am (oncle en arabe) qui est à la fois une formule de politesse mais aussi de familiarité. Le commerçant s’est alors levé et lui a expliqué que l’heure de livraison changeait pendant Ramadan. Le client, un habitué, lui a donc demandé de lui mettre de côté quelques baguettes en le désignant cette fois-ci par jari (mon voisin).

En observant cette scène, nous étions perplexes. Le commerçant venait juste d’affirmer que personne ne connaissait personne, mais nous venions d’être témoins d’une scène indiquant l’inverse.

Une fois le client parti, Am Mohamed s’est retourné vers nous toujours un peu hésitant. Nous avons repris la discussion en demandant si les habitants du quartier entretenaient de bons rapports. Il répondit qu’il était bien d’avoir des voisins pour s’entraider mais que ce n’était plus comme avant ; les gens se connaissent de moins en moins et c’était « chacun pour soi ». Après un moment de silence, il rajouta avec le sourire « Les Tunisiens sont bons…Il y a toujours de la générosité en Tunisie ».

Om Zeineb

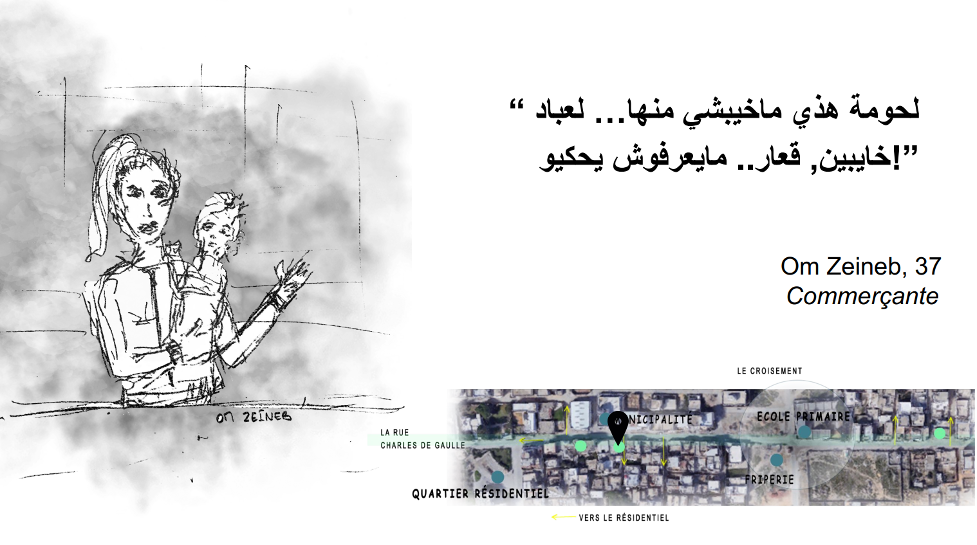

Image 3 : Om Zeineb – « Ce quartier-là ? Il n’y a pas pire ! ...Les gens ne maîtrisent pas l’art de parler. »

Dans une supérette, nous avons rencontré une jeune femme avec sa fille de 2 ans. Elle était très à l’aise et parlait fort. Elle nous a présenté sa fille qui n’arrêtait pas de nous regarder et de nous sourire. Les gens du quartier l'appelaient Om Zeineb (Om se traduit par mère en arabe. C'est une pratique courante de désigner les femmes -et les hommes- par le nom de leurs enfants ; dans ce cas, “mère de Zeineb”.)

En lui expliquant que nous voulions en savoir plus sur la vie de quartier, elle nous répondit sans hésitation « Ce quartier-là ? Il n’y a pas pire ! » Nous lui avons alors demandé pourquoi. En grimaçant, elle affirma avec véhémence : « Ce sont des véritables brutes les gens ici. J’ai passé deux mois à pleurer à cause d’eux. »

Elle continua « Je ne suis pas d’ici, je viens du Sahel [zone côtière entre Hammamet et Sfax] et je viens juste d’emménager et d’installer mon commerce ». Des clients entrèrent et interrompirent notre discussion. Ils parlaient d’une manière familière avec elle et accordaient beaucoup d’attention à sa fille.

La vendeuse répondait aux demandes de ses clients avec des mouvements prompts et un visage neutre. Elle semblait connaître les achats habituels de ses clients et répondait à leurs demandes avec diligence. La plupart d’entre eux cherchaient de la malsouka (des feuilles de pâte fine utilisées pour faire des bricks – un plat tunisien préparé spécialement pour la rupture du jeûne pendant le Ramadan), mais Oum Zeineb n’en avait plus. Elle leur recommandait donc d’aller chez Fatouma, dans une boutique voisine, afin de voir si elle en avait.

Et à nouveau, nous étions témoins de la même scène: les pratiques sociales ne reflétaient pas les paroles négatives de nos interlocuteurs.

Ça faisait seulement deux mois qu’Oum Zeineb était arrivée dans le quartier, et malgré ça, les gens la connaissaient déjà assez bien pour lui demander « pourquoi sa petite fille ne portait pas assez de vêtements alors qu’il faisait encore froid ?» Quant à elle, elle se rappelait facilement du fromage demandé habituellement par sa cliente en dépit du nombre des personnes fréquentant son hanout tout au long de la journée.

En se promenant dans Bhar Lazreg, une tension urbaine était certes perceptible. Pourtant les expériences et les intérêts communs impliquaient automatiquement une relation entre ceux qui habitaient et pratiquaient le quartier et ses commerces.

Ces moments du quotidien de Bhar Lazreg, ces interactions entre commerçants et habitants du quartier, nous indiquent que les hanouts jouent un rôle important au sein du quartier en créant un dynamisme relationnel. Est-ce donc ce cadre d’échange de proximité qui permet d’agir en solidarité malgré la tension ?

La solidarité ne nécessite peut-être pas forcément un sentiment de complicité envers l’autre, mais simplement de la compréhension et un minimum d’empathie. C’était peut-être le cas pour Oum Zeineb, elle qui admettait avoir souffert des mauvaises manières de ses voisins, mais n’hésitait pas à aider sa voisine à gagner plus de clients.