[Bu yazı, Jadaliyya Türkiye Sayfası Editörleri tarafından hazırlanan “Gezi'yi Hatırlamak: On Yıl Sonra Nostaljinin Ötesinde” başlıklı tartışma serisinin bir parçasıdır. Konuk editörler Birgan Gökmenoğlu ve Derya Özkaya tarafından hazırlanan serinin giriş yazısına ve diğer makalelerine buradan ulaşabilirsiniz.]

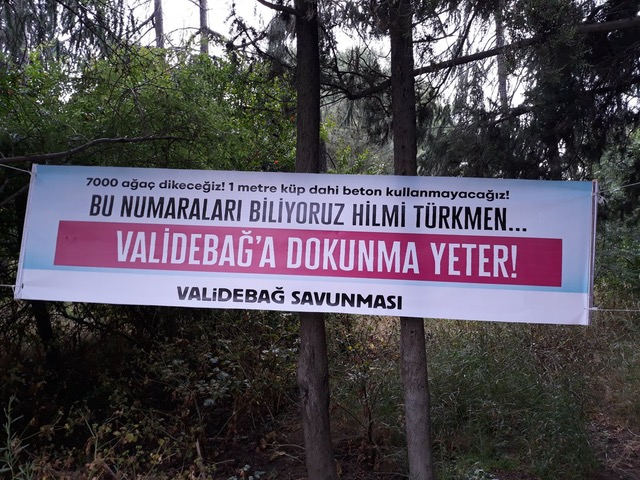

Validebağ Savunması (VBS), 2014 yılı sonbaharında, İstanbul’da bulunan Validebağ Korusu’nun Acıbadem sınırına komşu yeşil alan üzerinde, Üsküdar Belediyesi tarafından başlatılan kaçak inşaata karşı, başta Koşuyolu-Acıbadem semt sakinleri ve Gezi sonrası kurulan mahalle dayanışmaları tarafından yürütülen mücadele sürecinde ortaya çıkan bir sivil insiyatif, yaşam alanı savunucusu ve mahalle dayanışmasıdır.

Validebağ Savunması kurulduğu günden itibaren sadece Validebağ Korusu’nun doğal dokusunu korumak için verdiği mücadele ile yetinmeyip İstanbul ve pek çok başka kentte yürütülen çevre, ekoloji, ve kent hakkı mücadeleleri ile dayanışma içerisinde oldu, olmaya da devam ediyor.

Tamamen gönüllük temelinde bir arada bulunan bireylerden oluşan Validebağ Savunması, haftalık toplantılarına ve düzenli periyodlarla oluşturdukları faaliyet planları dahilinde kurdukları çalışma grupları ile yerel ve ulusal düzeyde mücadeleye devam etmekte.

10. yılında hem yerel direnişlerinde hem de Türkiye’de ekoloji ve kent mücadelelerinde Gezi’nin izlerini sürmek üzere Validebağ Savunması gönüllülerine kulak veriyoruz...

Gezi’nin hemen ardından yerel dayanışma ağlarında bir çeşitlilik, hem söylemsel açıdan hem de kolektif eylemler anlamında bir çoğulculuk gözlemlendi. Bugünden baktığınızda o süreci nasıl değerlendiriyorsunuz? 2013’ten bu yana geçen 10 yıl içerisinde Gezi’ye yaklaşımınız değişti mi?

Sibel Akyıldız: Benim de gözlemim Gezi’den sonra sivil inisiyatiflerin yani dayanışma ağlarının çeşitlendiği yönünde. Ben bunu sınıf yönetiminde adil olmayan, ona yapılan tüm itirazları ceza ile bastıran bir hocanın sınıfında ilk defa sesini çıkartan bir öğrenci gibi tahayyül ediyorum. Gezi bana göre, “yeter” diyerek isyan eden ve sonrasında tüm sınıfı peşinden sürükleyen biri gibi. Bir kere “hayır” deme cesaretini gösterdiğin anda ve bir kere korku eşiği yıkıldığı anda bundan geri dönüşü yok artık. Toplumdaki “hayır” deme cesareti bana göre Gezi isyanıdır. Ben bu cesaretin de aynı korku gibi toplumdaki her bireye sirayet ettiğini ve bu sebeple Gezi’nin ardından çeşitlenen kentsel toplumsal muhalefetin bu cesaretten beslendiğini düşünüyorum. Son 10 yıla bakınca Gezi’nin cesaretini kıracak iktidarın pek çok hamlesine rağmen yine de oradan edindiğimiz deneyimin yanımıza kar kaldığını düşünüyorum. Bugün Validebağ Savunması’nda halen mücadele vermeye devam ediyorsak, bunu muhakkak Gezi’den edindiğimiz cesaret ve deneyime borçluyuz diye düşünüyorum.

Mesut Öztürk: Gezi’nin ardından oluşan dayanışmalar, aslında Gezi sürecini sürdürmeyi temel alan yaklaşımlarla şekillendi. O dönemde devletin, bizleri Gezi Parkı’ndan çıkarmasıyla birlikte, mahallelere çekilmek ve oluşan o müthiş birlikteliği sürdürmeyi amaçlıyordu. Bunun yanısıra, (mahalle/yereller dışında), kent hakkı/ekoloji/gıda meselelerine odaklanan oluşumları da Gezi’nin devamı olarak görüyorum. Son 10 yıl içerisinde ülkenin içinden geçtiği siyasal/ekonomik/sosyal değişim, ister istemez Gezi’yi yeniden düşünmemizi gerektiriyor. Temelde Gezi’ye yaklaşımım aynı kalsa da, Gezi’nin “ateşinin” bir süreliğine de olsa söndüğünü söylemek yanlış olmaz sanırım.

Figen Küçüksezer: Gezi sonrasında sivil inisiyatifler açısından sanırım en büyük değişiklik "forum"ların başat örgütlenme modeli haline gelmesi oldu. Merkezi olmayan bu yapılanmalar, birbirleriyle dirsek temasını sürdürerek hem yerele müdahil olmayı, hem ortak sosyal ve siyasi tepkiler vermeyi başardılar. Bu giderek ortak platformlar, güç ve eylem birlikleri oluşturma çabalarının da başlangıcı oldu. Çevre ve kent hakkı, gıda egemenliği ya da sosyal hak savunuculuğunun yanı sıra politik güç birlikleri de oluşturuldu. Bunların bir kısmı zaman içinde dağılmakla birlikte bir kısmı bugüne kadar varlığını sürdürebildi. Forumlar yer yer mahalle meclisi çalışmalarına evrildi. Bunların hem yerelden örgütlenme modelleri olarak, hem doğrudan demokrasi deneyimleri olarak çok değerli olduğunu düşünüyorum. Gezi'nin hepimize verdiği, değiştirmek istediğimiz şeyler için ayağa kalktığımızda birlikte başarabileceğimiz duygusunu ise paha biçilmez buluyorum.

Peki bu süreç Türkiye’de değişim umudu ve arzusu taşıyan kesimler için ne tür siyasal imkanlar sundu ya da sundu mu? Bu imkanlar nasıl/ne kadar değerlendirilebildi? Kendi deneyiminiz üzerinden bir değerlendirme yapabilir misiniz?

Figen Küçüksezer: Türkiye'de giderek artan neoliberal dayatmacı, milliyetçi, siyasal islamcı baskı karşısında sivil inisiyatif, kooperatif, dayanışma ve meclisler her alanda kollektivist alternatiflerin yeniden ve ortodoks/gelenekçi olmayan biçimde tartışılmasını da beraberinde getirdi. Yerel örgütlenmeler siyaseten bir aidiyet hissetmeyen insanların hak savunusu temelinde bir araya gelmesini sağladı. Bu süreç siyasetin daha önce çok da öne çıkarmadığı doğa hakkı, iklim krizi, LGBTİ+ hak mücadelesi gibi başlıkların sol partilerce benimsenmesine ve bu mücadelelerin siyasi örgütlerde temsil edilmesine de yol açtı. Bu durum yerel mücadelelerin siyasi platformlara da taşınmasını ve seslerinin daha güçlü çıkmasını sağlıyor. Ancak hak ihlallerinin her gün yaşandığı, gündemi her zaman yoğun olan bir ülkede siyasi kadroların yerel dayanışmalarda yeterince yer aldığını söyleyemeyiz.

Mesut Öztürk: İki boyutta ele alabiliriz: İlki, o güne kadar bizi muhatap almayan, aşağılayan, yok sayan hükümetin bizi muhatap kabul etmek durumunda kalması idi. Devlete muhatap olmayı önemli buluyorum. Diğer boyutu, Gezi sonrası oradan çıkan enerjiyi konsolide etmek isteyen ve kaçınılmaz olarak bir araya gelmeyi zorunlu kılan Birleşik Haziran Hareketi (BHH) gibi oluşumlar ortaya çıkardı. Gezi’nin bir başka önemli boyutunun, onun sınıfsal niteliği olduğunu düşünüyorum. Burası bize yeniden sınıf kimdir, kimlerden oluşur sorularını sordurdu. Bir diğer yönden, yatay örgütlenme, forum, oydaşma, müşterekler gibi kavramları hayatımıza soktu. Bunlar o güne kadar, teoride okuduğumuz ama hiç pratiği ile karşılaşmadığımız, yaşamadığımız kavramlar/durumlardı. Gezi’nin yarattığı imkanların genel olarak olumlu şekilde değerlendirilebildiğini düşünüyorum. Türkiye siyasal hayatında 15-16 Haziran sonrası belki de en büyük armağandı ve aradan 10 yıl geçmesine rağmen, hayat artık herkes için “Gezi öncesi ve Gezi sonrası” olarak devam ediyor. Buna devlet de dahil. Eksiklik olarak, kuşkusuz emek hareketi ve Kürt hareketi ile ilişkilenememesi söylenebilir.

Dayanışmalar çoğu zaman “Gezi’nin bakiyesi” olarak karşımıza çıkıyor. Gezi’den yerel dayanışmalara kalan nedir ve bunlar zamanla nasıl bir değişime uğradı?

Sibel Akyıldız: Benim kanaatimce de bu oluşumlar Gezi’nin bakiyesidir çünkü Gezi’den edindikleri pek çok deneyim var. Klasik örgütlenmelerde olmayan ne varsa çoğunlukla Gezi’de öğrenilerek sonrasında bu deneyimler dayanışmalara ve savunmalara aktarıldı. Neydi bu deneyimler? Yatay örgütlenme yapısı, aktif bir sosyal ağ kullanımı, yardım yerine dayanışmanın temel alınması gibi işleyiş, örgütlenme biçimi ve tecrübelerdi.

Mesut Öztürk: Ben de en önemlisinin işleyişe ve örgütlenmeye dahil konular olduğunu düşünüyorum. Artık kimse hiyerarşik bir örgütlenmeyi mücadele biçimi olarak teklif dahi edemiyor. Herkese açık olma, söz hakkı, ikna süreçleri, oydaşma gibi konularda tecrübe kazanmak hepimizi çok yordu 😊

Gezi sonrası kurulan benzer dayanışma ağları maalesef bu sürekliliği yakalayamadı ve bir süre sonra sönümlendi. Sizin bu sürekliliği sağlayabilmenizin ardında yatan nedenler nelerdir?

Sibel Akyıldız: Benim bu durum ile ilgili tespitim, aslında bu birlikteliği sıcak tutanın yerel yönetimlerin ya da iktidarın kendisi olduğudur. Şöyle ki, ortada halen güncel bir sorun var, yani Validebağ Korusu sistematik bir biçimde 2 senede bir yeni bir koruyu dönüştürme projesinin konusu oluyor. Toplumsal mücadeleyi bir arada tutan, çözülmemiş bir sorunun varlığıdır kanımca. Muzaffer Şerif’in belirtmiş olduğu gibi, bir araya gelmeleri mümkün olmayan grupları bir araya getirebilen yegane şeylerden biri ortak bir sorunun varlığıdır. Validebağ Savunması’nın bu sebeple sönümlenmeye ne zamanı ne de fırsatı oluyor çünkü onu her zaman bir arada ve diri tutan bir sorunu var. O sorun da Validebağ Korusu’nun siyasi yönetim tarafından türlü proje adı altında imara açılmaya çalışılması.

Figen Küçüksezer: İnat... Şaka bir yana sebat önemli bir faktör tabii. Validebağ Savunması’nın oluşmasına yol açan olay, Validebağ'a komşu alandaki kaçak camiye karşı başlatılan direniş. Bundan çok önce başlamış olan Validebağ Korusu mücadelesinden yıllar içinde vazgeçilmemiş olması, bizim için önemli bir motivasyon kaynağı oldu. Koru'nun hepimiz için bir yaşam alanı olması, komşu olmamız, birbirimizle yalnız örgütsel değil, insani ilişkilerimizin olması da katkıda bulundu. Bir de Validebağ Korusu'na saldırılar hep sürdüğünden bunlara karşı farklı mücadele biçimleri geliştirmek zorunda kalmamız, pandemi sürecinde evde kalmanın getirdiği teorik çalışmalara ağırlık verme (pandemide çevrimiçi gerçekleştirdiğimiz seminerler dizisi ve bunların çıktısı olan sonuç raporunun hazırlanması ile İstanbul Planlama Ajansı’nın düzenlediği çalıştay sonucunda ekosistem tabanlı yönetim planı çalışmalarında yer almak) ve ne mutlu ki şimdiye kadar önemli bir yenilgi yaşamamış olmamız da Validebağ Savunması’nın bir arada kalmasını sağlayan etmenler bence.

Mesut Öztürk: Diğer pek çok dayanışma, ilgilendiği konu itibariyle başarıya ya da yenilgiye uğradığı için bir nevi “konusuz” kaldı. Örneğin Kanal Istanbul, Kuzey Ormanları, Sulukule vb. Oysa Validebağ’da bitmeyen bir süreç var. Zaman zaman düşse de, devletin koru ile ilgili aksiyonlarına karşı hep bir tetikte olma hali söz konusu. Bir diğer fark da, Validebağ bu yerele dayanan bir mahalle dayanışması. Mahalleli/komşu olma halinin ve Validebağ ile başlayan tanış olmanın, artık çok sıkı dostluklar/yoldaşlıklar yarattığını biliyoruz. Bir mahalle kültürü oluştu ve bundan keyif alıyoruz. Buradan üreyen başka birliktelikler oluştu. Koşuyolu Kooperatifi, “İlk 72 Saat” çalışması, muhtarlık seçim destek çalışmaları bunlardan bazıları.

Süreç içerisinde yaşadığınız sorunlar, tıkanıklıklar oldu mu? Olduysa nasıl aştınız ya da aşabildiniz mi?

Mesut Öztürk: Tıkanma kaçınılmaz olarak yaşanıyor. Hayatın sadece buradan ibaret olmaması, ilgi alanlarındaki değişiklik, yorgunluk işleyişte kimi insanların sürecin dışında kalmak durumunda olması vb. Yatay örgütlenmelerin en büyük handikaplarından biri olan, gönüllülük ve hesap verilebilirlik konularında yaşadığımız tıkanıkların bir kısmının aşıldığını ama önemli ölçüde bu tıkanıklarla yaşamak durumunda olduğumuzu söyleyebilirim. Tecrübe etmeye devam ediyoruz.

Sibel Akyıldız: Aksi mümkün değil zaten. Tabii ki sorunlar, kırılmalar oldu zaman içerisinde çünkü belki de normal şartlarda bir araya gelmesi mümkün olmayan bir grup insanın bir sorun etrafında bir araya gelmesinden bahsediyoruz. Dolayısıyla sorunun ortadan kalkma ihtimali ortaya çıkınca ya da sorunun hayati olmadığı düşünüldüğü zamanlarda kopmalar, kırılmalar oldu elbette ancak bu durumu negatif tarafa değil tam tersine odaklanmaktan yana kullandık sanırım. Tamamen farklı huyda, suda, karakterde kişiler olarak nasıl bir araya geldiğimize, birlikte bir mücadele sürdürdüğümüze, sırf tanış olma halinin bile kıymetli olduğuna odaklanmaya çalıştık ve bence çoğu durumda da bu yöntem işe yaradı diye düşünüyorum.

Figen Küçüksezer: Oldu tabii, her dayanışmada olduğu gibi. Özellikle başlangıçtaki motivasyonun azalması bir noktadan sonra büyümeyi engellediği gibi, aktif çalışan insan sayısında bir azalmaya da neden oluyor, oysa iş yükü aynı kalıyor, hatta zaman içinde artıyor. Sonuçta bir avuç gönüllüyle yetişemediğiniz işler, yetişebildiklerinizden fazla oluyor. Bu durum grup içinde gerilimin artmasına ve zaman zaman kopmalara yol açıyor. Doğrusu çoğunu aşamadık, başladığımız döneme göre ciddi kan kaybı yaşadık ama artık aktif çalışmayanlarla dahi ilişkileri, biraz da başka alanlarda da birlikte emek veren komşu, mahalleli olma özelliklerimizle sürdürmeyi başardık.

Bugünden baktığınızda Gezi yerelinizde ne tür değişiklikler yarattı? Bu değişikliklerde Validebağ Savunması’nın rolü nedir?

Figen Küçüksezer: Kadıköy merkeze yakın, sosyal demokrat, nüfus hareketlerinin fazla olmadığı, hala nüfusun önemli bir kısmının birbirini tanıdığı ve zaten mahalle kültürü olan bir yerelden bahsediyoruz. Gezi’den önce de sivil inisiyatiflerin varlığı bu kültürü pekiştirmiş. Gezi’den sonra ise her yerde olduğu gibi önce park forumları ile ortaya çıkan yurttaş eylemlilikleri, giderek çevre ve kent hakkı (Validebağ Savunması), gıda egemenliği (Koşuyolu Koop), afet planlama çalışmaları (Koşuyolu İlk 72 Saat), anayasa referandumunda muhalif oyları örgütleme (Hayır Meclisi), bölgedeki mahallelerle ortak çalışma yürüterek dayanışmalar adına muhtar adayı çıkarmak ve seçtirmek, mahalle meclisi, Covid döneminde yerel dayanışma ağı oluşturmak gibi çok çeşitli örgütlenme modelleri ortaya çıktı. Validebağ Savunması bu çalışmaların tümünde ya bizzat örgütleyici ya da aktif katılımcı olarak yer aldı.

Mesut Öztürk: Gezi’nin en önemli katkısı, aynı mahallede yaşayan insanların birbirlerini Gezi ve Gezi sonrası mahalle dayanışmalarında tanımış olmaları. Gezi’nin bir ortak değer haline gelmesi, adeta hepimizin ortak dava arkadaşlığına götürdü. Bir de şunu söylemek mümkün. Başka pek çok mahalle dayanışması ya da forumda, gençler ağırlıktayken, bizim mahallede, bir taraftan 50 yaş üzeri eski tüfek sosyalistler ile hayatında ilk defa bir mücadelenin parçası olarak sokağa çıkan, özellikle kadınların birleşimlerinden oluşmasıdır. Validebağ Savunması’nın burada oynadığı rol, bir mahalle meselesi olarak koru mücadelesiyle harekete geçen insanların bilinç sıçramasıyla, ülkedeki pek çok diğer meseleyle ilişkilendirmesi ve harekete geçirmesi oldu. Yırca’dan Soma’ya, Suruç’dan 1 Mayıs alanlarına kadar..

2013’ten bugüne Gezi’de deneyimlenen kolektivizm ve dayanışma pratikleri farklı toplumsal ve siyasal bağlamlarda çeşitli şekillerde yeniden yaratılmaya çalışıldı. Gezi sonrası deneyimlenen mahalle dayanışmaları ve Covid sürecindeki yerel dayanışma ağları bunlardan bazıları. Ayrıca orman yangınları, sel gibi afet hallerinde de toplumun benzer kesimlerinin hızlıca mobilize olabildiğine tanıklık ettik. Son olarak 6 Şubat’ta yaşadığımız deprem felaketinin ardından da yine halkın kendi dayanışma ağlarını ivedilikle kurabildiğine, tüm kısıtlı imkanlarına rağmen birlikte temel ihtiyaçları karşılamaya yönelik adımlar attıklarını gördük. Sizce bu tarz dayanışma ağlarını sürekli/kalıcı kılabilmenin önündeki engeller nelerdir? Bu engelller nasıl aşılabilir?

Sibel Akyıldız: Biliyoruz ki toplum da aynı toplumsal mücadeleler gibi bir devinim halinde alevlenir, söner, yeniden alevlenir. Tüm bu süreç içerisinde dayanışma ağlarının da şekillendiğini düşünüyorum. Yani tek bir ağ, yöntem ya da tarzın bir diğerine uyabilmesi ya da eklemlenebilmesi pek de mümkün görünmüyor çünkü toplumsal mücadelenin kendisi de değişiyor. Dolayısıyla bir şeyi sürekli kılmak dünyanın tabiatına aykırı diye düşünüyorum. Şayet Türkiye özelinde konuşuyorsak, biz hali hazırda dayanışma ağları konusunda oldukça maharetli bir toplumuz çünkü halk olarak hep yek, hep tek başınayız. Bu durumda olmak ve bunu içselleştirmek dayanışmayı oldukça güçlü kılıyor. Bu sebeple bu toplumda dayanışma ağları her daim güçlü kalmıştır. Bunun önündeki en büyük engellerden biri bana göre liyakatsiz yöneticiler ve topyekün halk birlikteliğinden rahatsız olan iktidarların varlığı. Ama işte tam da bu yüzden dayanışma ortaya çıkıyor.

Mesut Öztürk: Bu konuda bu ağları kalıcı kılabilmenin mümkün olmadığını ayrıca buna gerek de olmadığını düşünüyorum. Çünkü bu düşüncenin arka planında çok ciddi bir ideolojik yaklaşım var. O da devletin rolü ile ilgili. Özellikle deprem gibi afet sonrası yaşanan duruma karşı, reaksiyon olarak bir araya gelme ve örgütlü bir yardım kampanyası örgütlemek önemlidir ama bunun bir sonraki aşama ile, yani devleti harekete geçirmeyi talep etmeyi içermesi de gerekir. Ancak çoğu zaman yaşadığımız bu değil. Devletin yapması gereken işlevlerini talep etmeyen, bir anlamda devlet ile karşı karşıya gelmeyi göze almayan/alamayan, bunun yerine devleti sürecin dışında bırakarak dayanışma örgütünü onun yerine koyan bir anlayışın yanlış olduğunu düşünüyorum. Zaten tıkanmada bir süre sonra, tam da bu nedenle ortaya çıkıp, dayanışma sönümleniyor.

Figen Küçüksezer: Tanımlanmış bir gereksinime yönelik olarak örgütlenen dayanışma ağlarının o gereksinim ortadan kalktığında sonlanması doğal. Süreklilik arz eden gereksinimleri karşılayacak (örn. dezavantajlı toplum kesimleriyle dayanışma) örgütlenmeler ise çoğunlukla hem insan gücü hem maddi kaynak eksikliği nedeniyle uzun ömürlü olamıyor. Merkezi ve yerel yönetimlerin bu konuda vereceği maddi destek (mekan sağlamak, gönüllü profesyonellerin ücretini karşılamak, malzeme tedariki vb) bu dayanışma ağlarının kalıcılığını sağlayabilir.

Eklemek istedikleriniz?

Teşekkürler…