[This article is part of a special dossier on fandom and politics in the Southwest Asian/ North African (S.W.A.N.A.) region. Read all of the pieces, as well as the introduction, here.]

I encountered the field of fan studies for the first time in 2015, at a difficult political moment in my life as a displaced woman scholar from Syria in the United States. That moment coincided with the rise of Trump and worsening conditions of war and displacement in Syria. I was starting my PhD training at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and felt that I had finally found, through cultural studies, theoretical tools with which I could describe my politically charged experiences as a fan of television and the experiences of other Arabic-speaking fans that I was witnessing in online communities, mainly on Facebook. I began exploring questions of how fans’ cultural participation can contribute to our understating of non-traditional political participation.

Since then, I have studied two groups of fans: the Arab fans of Game of Thrones; and displaced fans of Syrian TV drama serials. Fandom in the Arabic speaking world is an understudied aspect of media globalization, generally studied only indirectly. For instance, scholars have previously taken up questions of nationalism and modernity by studying the popularity of Arabic popular television series such the Syrian show Bab Al-Hara i.e.: The Gate to the Neighborhood (Al-Ghazzi, 2013) and the Egyptian show Al-Helmiya Nights i.e.: The Nights of Hilmiyya Neighborhood (Abu-Lughod, 2005). Others have explored the appeal of Arabic-dubbed Mexican and Turkish television serials as providing Arab audiences with counter-hegemonic alternatives to the American domination of TV programming internationally (Kraidy and Al-Ghazzi, 2013; Kraidy,1999). By contrast, my work focuses on fans of local and international television as an interpretive community (Radway, 1984; Jenkins, 1992), exploring the dialogic, affective, and collaborative articulations of fans’ cultural and political formations through media and popular culture. My projects are based on online interviews with fans as well as textual analyses of their posts.

Figure 1: Katty Alhayek arrived at Game of Thrones Live Concert Experience featuring composer Ramin Djawadi at the DCU Center in Worcester, Massachusetts, United States (September 29, 2018).

My first research project on fandom engaged with transnational fan objects and practices around Game of Thrones (GoT) in the Arab world (Alhayek, 2017). I have been a fan of GoT since 2012, the year I arrived at the United States from Syria and started a Master’s program at Ohio University. I found myself attached to the world of GoT and using its characters' motives, journeys, and agendas to explain to my American colleagues the real-world trajectory and complexity of the Syrian conflict. I got attached to the Stark family’s experiences of displacement, Daenerys' longing for a homeland, and Tyrion’s struggle with his ambiguous position of marginality and privilege. I was drawn to the American world of GoT fandom and obsessed with fans’ speculative fiction. However, my ethnicity as a Syrian and native speaker of Arabic made me yearn to find an Arabic-speaking fan community of GoT. In 2014, I found just such a community, and a massive one, on Facebook. As I interacted with the “Game of Thrones–Official Arabic Page” (GoT-OAP), I became interested in the cultural production through which these Arab fans shared their experience of cultural consumption. As of 2016, the page had over 240,000 Arab followers, and was the largest and oldest of its kind among competing similar pages. Although this specific page no longer exists, similar pages continue to flourish on Facebook.

In this project, I noticed that the Arab fans of this show are different from the above-mentioned audiences of the popular Arabic, Mexican, and Turkish serials. I argue that GoT Arab audiences are part of the global fandom of quality television or what is referred to as “Prestige TV.” This type of TV mainly targets global elite audiences who are highly educated, affluent, and male (Hassler-Forest, 2014). The characteristics of the Arab fans of GoT I worked with reflect this observation. In fact, 80% of the GoT-OAP followers were men; many of whom were educated, highly skilled, and tech-savvy professionals. As a woman fan, I recognize that “Prestige TV” shows like GoT still cater to women viewers by presenting diverse, strong women characters like Arya, Brienne, Cersei, Daenerys, Sansa, and Olenna Tyrell. Of course, in a predominantly Western series all these women are white. Thus in this project, I showed how Arab fans responded to the whiteness and Eurocentrism of GoT and their sense of racial difference by producing hybrid posts and memes that reflect their local contexts and lived experiences. For example, one of GoT-OAP administrators’ favorite characters is Arya Stark. In figure 2, the fans imagine a conversation between George RR Martin and his wife by choosing three sequential moments from an Egyptian show. An Egyptian actress and actor are imagined as Martin and his wife in an argument over the destiny of Arya in which the wife is threatening Martin to not kill off Arya unless he wants to sleep on the couch. This meme was inspired by a true anecdote of Martin’s wife’s fondness for Arya and the consequences of killing Arya off on the couple’s marriage (Harvey-Jenner, 2015).

Figure 2: An imagined argument between George RR Martin and his wife.

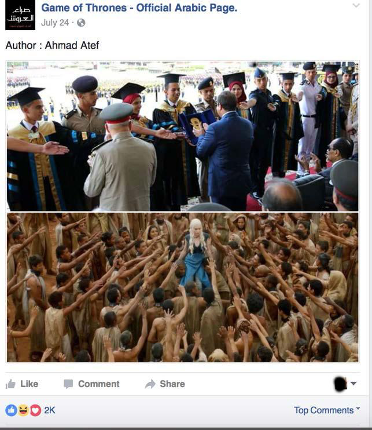

Other posts, such as figure 3, use the show’s imagery for political satire, in this case ridiculing Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egypt’s current president. In the post below, el-Sisi is compared to Daenerys, represented as a “savior" while being in fact a ruthless dictator.

Figure 3: A hybrid post that compares el-Sisi with Daenerys.

Figure 4: A screenshot of “Game of Thrones & House of the Dragon Arab Fans” group on Facebook as of July 20, 2022.

After much anticipation and high expectations from the fan community, House of the Dragon (a prequal to Game of Thrones) premiered on August 21, 2022, drawing a record viewership of nearly 10 million across all HBO’s platforms (Murphy, 2022). It is difficult to estimate the actual size of the international audience, because this viewership number does not include, for example, illegal downloads and other ways of viewing through reginal networks. Today, the GoT fandom in the Arab World continues through Facebook communities like “Game of Thrones & House of the Dragon Arab Fans,” which has over 395.2K members (Figure 4), and “House of the Dragon Arab Fans,” which has over 45K members. In these communities, Arab fans follow the news about the show’s production. They also express their nostalgic feelings to the time when GoT was airing, their unhappiness with how GoT ended (Figure 5), and their excitement about the expansion of the GoT universe (the way Marvel Studios did with the Marvel universe) to anticipated spinoffs such as a sequel series centered around the Jon Snow character.

Figure 5: In this meme, Arab fans use Egyptian comedian and actor Adel Imam to channel their unpleasant feelings about the GoT ending. The meme conveys that it’s a perfect and great series, but its ending was substandard.

My second project on fandom explores how displaced Syrian audiences challenge the harsh conditions they live in by using social media to participate in conversations with creators of TV dramas that resemble their lived experiences of war and displacement (Alhayek, 2020). When we think about the Syrian war and subsequent refugee crisis, we don’t tend to imagine these displaced populations as fans and active audiences of entertainment. However, since 2013 I have observed the interactive trend on Facebook, of befriending, specifically during Ramadan, writers of acclaimed Syrian TV drama serials such as the 2013 Manbar Al Mota (Platform of the dead); the 2014 series Qalam Humra (Lipstick); the 2015 Ghadan Naltaqi (We’ll Meet Tomorrow); and the 2022 Kasr Adm (Breaking Bones.)

Figure 6: A fan praise of Ghadan Naltaqi on the Facebook page of the show’s creator Iyad Abou Chamat on 15 November 2015.

From the early 1990s until the war, the Syrian drama industry flourished and was known for the high quality of its content and production (Kraidy, 2006). Many of the Syrian drama creators became known for their commitment to social and political transformation, exposing structural inequalities and the corruption of the ruling class in Arab societies (Salamandra, 2011). However, after the 2011-Syrian Uprising and subsequent war, the quantity and quality of TV drama declined significantly. Nevertheless, some high-quality shows continued to be produced, for instance, Ghadan Naltaqi. In my research on fan engagement with that show, I explore questions like how such post-2011 top-quality shows (albeit rare) symbolize for the fans the continuity of the respected tradition of Syrian drama’s critiques of power structures. It also provides fans with cultural references that invoke their sense of dignity and pride and alleviate their feelings of loss and humiliation (Zeno, 2017). I demonstrate that the interactive, emotional relationship between fans and drama creators serve as political interventions to cope with a highly polarizing conflict and create healing spaces at a critical remove from violent media discourses.

Going forward, I hope to continue engaging with questions around fandom of “Prestige TV”, race, gender and class. I am particularly interested in the affective qualities of fandom and the complex ways in which fandom and politics intersect and how that contributes to our understanding of large power relations in society. In this regard, I want to think more about the definition of “Prestige TV” in the local context of Syria. I also want to explore how fandom of local “Prestige TV” like Ghadan Naltaqi is different or similar to fandom of global “Prestige TV” like Game of Thrones. This pursuit is part of larger, ongoing conversations in the fields of

fan studies and critical cultural studies (Chin and Morimoto, 2013; Pande, 2018; Reinhard and Miller, 2020) about the need to examine racial and cultural identities in global online fandom spaces and to question how whiteness affect the workings of media fandom communities.

[Note: An earlier version of this article was published in Henry Jenkins' "Global Fandom Jamboree Series" in 2022.]

References

Abu-Lughod, L. (2005). Dramas of nationhood: The politics of television in Egypt. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Al-Ghazzi, O. (2013). Nation as neighborhood: How Bab al-Hara dramatized Syrian identity. Media, Culture & Society, 35(5), 586‒601.

Alhayek, K. (2020). Watching television while forcibly displaced: Syrian refugees as participant audiences. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 17(1), 8-28.

Alhayek, K. (2017). ‘Emotional Realism, Affective Labor, and Politics in the Arab Fandom of Game of Thrones.’ International Journal of Communication, 11: 1-24.

Chin, B., & Morimoto, L. H. (2013). Towards a theory of transcultural fandom. Participations, 10(1), 92-108.

Harvey-Jenner, C. (2015, July 15). The big reason Arya Stark won’t get killed off Game of Thrones any time soon. Cosmopolitan. Retrieved from https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/entertainment/interviews/a37208/arya-stark-maisie-williams-killed-off-game-thrones/

Hassler-Forest, D. (2014). Game of Thrones: Quality television and the cultural logic of gentrification. TV/Series, (6), 160‒170.

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kraidy, M. M. (1999). The global, the local, and the hybrid: A native ethnography of glocalization. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 16(4), 456‒476.

Kraidy, M. M., & Al-Ghazzi, O. (2013). Neo-Ottoman cool: Turkish popular culture in the Arab public sphere. Popular Communication, 11(1), 17‒29.

Kraidy, M. M. (2006.) ‘Syria: Media Reform and Its Limitations.’ Arab Reform Bulletin 4, no. 4. http://carnegieendowment.org/files/kraidy_may06.pdf

Murphy, C. (2022, August 23). “House of the dragon” flies high, pulls record-breaking numbers for HBO. Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2022/08/house-of-the-dragon-flies-high-pulls-record-breaking-numbers-for-hbo

Pande, R. (2018). Squee from the margins: Fandom and race. University of Iowa Press.

Radway, J. (1984). Reading the romance: Women, patriarchy, and popular culture. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Reinhard, C. D., & Miller, J. (2020). Academic dialogue: Why study politics and fandom?. Transformative Works and Cultures, 32, 1-8.

Salamandra, C. (2011.) ‘Arab Television Drama Production in the Satellite Era.’ In Soap Operas and Telenovelas in the Digital Age, edited by Diana Isabel Arredondo Ríos and Mari Castañeda, 275-290. New York: Peter Lang.

Zeno, B. (2017.) ‘Dignity and Humiliation: Identity Formation among Syrian Refugees.’ Middle East Law and Governance 9, no. 3: 282-297.