[This talk was given on the closing night of On This Land, a collaborative exhibition between Alserkal Arts Foundation, Barjeel Art Foundation, and the Palestinian Museum. The exhibit ran between 19 November and 26 November 2023 at Concrete in Dubai. Above are a selection of photographs from the exhibit.][1]

I have worked on and written about Palestinian cultural politics for fifteen years. And yet, over the past fifty days words have felt inconsequential in the face of Israel’s genocide. For nearly two months, live streamed on our screens, Gaza has been turned into a dystopian gallery of images that lay bare the horrors of Israel’s annexationist and annihilationist policy towards Palestinians, their institutions, and their land.

This of course leaves us with a great deal of anxiety about the future of Palestine. My small intervention today seeks to offer a cultural lens on the current crisis, specifically Israel’s violent process of deculturalisation, in the hope of making some sense of the endless nightmare we are all witnessing.

On this Land exhibition poster. Copyright: Alserkal Arts Foundation.

We have all seen endless horrific images of the unspeakable inhumanity that has been forced on the oppressed, rendering Gaza unliveable: a decaying site of destruction, death, and disease. Collectively, these genocidal images serve as an archive of Israel’s culture of violence and undisguised cruelty that seeks to make Palestine invisible. By stark contrast, the images that surround us in this gallery represent an archive of survival against displacement, ethnic cleansing, and ongoing colonial erasures. More than just a celebration of Palestinian artists, this exhibition reminds us of the collective love, care, and hope we share for Palestine and its survival. Making our steadfast cultural history visible beyond the expectant images of destruction and despair is an empowering show of solidarity and a reminder of the importance of collective action.

In fact, the spirit of this exhibition reminds me of a year-long project I worked on that culminated in a cultural festival held in Gaza in May 2012 – an event that was sandwiched between two Israeli aggressions that took place that year.

The two times I entered Gaza, it was an overwhelming experience in both positive and negative ways. What is most unnerving about being in Gaza is the pervasiveness of Israel’s presence, even if it exists as an absence. From the moment you enter its besieged borders through the Rafah crossing, you soon realize Gaza’s intentional isolation from historic Palestine and the world. In addition to the restrictions of movement and goods, Israel also controls Gaza’s sea and air. You feel this when you look out to the sea at night and see the glaring flood lights that Israel has placed in Gaza’s waters to prevent Palestinian fisherman from accessing their seas.

Another strategy of psychological warfare used by Israel is the breaking of the sound barrier, causing sonic booms that remind Gaza’s residents in their everyday moments that Israel is in control of their air space. The killing of the four Baker boys by Israeli airstrikes during the 2014 aggression, when they were simply playing football on the beach, remains a stark reminder that Gaza is not merely an “open-air prison,” but an enclosed extermination camp. This reality is what makes the recent images of the occupation forces erecting their flag on Gaza’s shores and singing the national anthem earlier this month even more painful, as it serves as another reminder of the power inequalities and visual dissonance between Palestine and Israel's relationship to public space.

Despite the unavoidable restrictions imposed on the besieged territory, for a brief moment in 2012, our group succeeded in rupturing the cultural siege by bringing in a large group of international cultural practitioners, writers, artists, musicians, and many books. On the closing night, we held a concert in Rashad al Shawa [2], a cultural center that was built in the late 1980s and named after the city’s one-time mayor. Many people turned up to the venue; it was packed full of the young and old, men and women. I will never forget, after singing revolutionary songs together, one woman turned to me and said: “This is the first time in years that I have felt alive.”

It was a sentiment that echoed from students, audiences, and our volunteers throughout the week-long festival. The importance of connecting and gathering with other Palestinians like myself who were born in the diaspora, our Egyptian neighbours, and artists from elsewhere‚ was a reminder of the right to live, not just the right to survive. Of course, in moments of crisis, food, aid, and medical supplies are the most crucial for keeping people alive; but, it is culture and exchange with community that gives people the feeling of being alive.

The Deculturalization of Gaza

Israel’s recurring strategy of affixing visual terror onto the landscape of Gaza through their ‘mow the lawn’ policy—which has now intensified to razing the enclave—is designed to warn Palestinians of their erasure from the land. As I wrote back in 2014, during Israel’s Operation Cast Lead, the images we are seeing today are not a spectacle of exception. Rather, Gaza's scorched earth should be read as a metaphor that lays bare the edifice of Israel's policy: one of inevitable destruction and the denial of an autonomous Palestinian future.

For over 75 years, historic Palestine has been aggressively re-territorialized, and as with Gaza today, de-territorialized. Since the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, Israeli occupation forces have worked to fragment Palestinian society into separate units that ruin their collective will for national unity. Through advanced militarism, Israel's spatial re-ordering of Palestinian society into Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the West Bank, is a physical and cognitive fragmentation that has gone unchallenged by the international community; hence, why our call for freedom across historic Palestine, from the river to the sea, has been absurdly deemed as controversial by Western genocidal apologists.

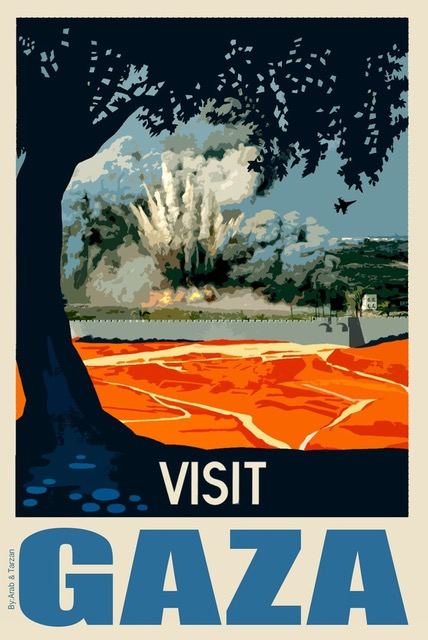

Arab and Tarzan, Visit Gaza, 2014.

Back in 2014, when Israel was once again imposing disproportionate violence on Gaza, the satirical poster by Gaza duo Arab and Tarzan was released. I wrote about how the reappropriation of this famous tourism poster holds a double irony when thinking about the future of Palestine within the global economy. Unlike Jerusalem, Gaza has no recognizable symbolic skyline for many of us; the image it brings to mind is warfare, rubble, and underdevelopment. As a redundant city brand, Gaza does not fit the “logic of marketability”[3] that has become a central tenet of neoliberal cultural success in which countries, cities, or regions are able to brand themselves effectively and become key players on the world stage.

Additionally, the artwork shatters the Israeli myth that Gaza could have been “the Singapore of the Middle East” had it not chosen the path of resistance. We see this accusation continue today, with Netanyahu claiming in the Knesset at the start of this genocide that:

They [Hamas] want to return the Middle East to the abyss of the barbaric fanaticism of the Middle Ages, whereas we want to take the Middle East forward to the heights of progress of the 21st century.

This false logic was once again peddled by Hilary Clinton in her recent appearance on the popular American talk show, The View, when she argued that “the Palestinians deserved to have a productive, successful economy in Gaza, [but] Hamas came in and basically destroyed all of that.”

Blaming Gaza for its failure to develop as a tourist site of economic and cultural development is a delusion at best, and completely overlooks Israel's intensified economic, political, and military control over the area for decades. Since 1948, Israeli censors have worked to control Palestinian cities by erasing any form of visual or cultural expression that asserts Palestinian nationalism or that suggests that Palestinians are a nation with a cultural past. For example, one of the first laws Israel enforced following the annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967 was for all cultural and biblical sites to come under Israeli administration. This process of deculturalization sought to historically ground an Israeli connection with the land while simultaneously dislodging a Palestinian one and historical narrative.

Similarly, the ongoing fragmentation of historic Palestine by separation barriers and the archaeological expropriations already undertaken since 1967 work to visually alter the historic landscape to reinforce the Jewish right to the ancient Holy Land. As such, Israel is better able to safeguard its historical perspective within the political arena, which is why the international community are often willing to accept their securitization narrative at the expense of the Palestinian cultural narrative.

Today, despite the 15,000 plus deaths, and 1.7 million displaced Palestinians in Gaza, the dominant Israeli logic continues to state that Gaza’s destruction is the outcome of the Hamas policy of using civilian infrastructures to house weapons. It argues without evidence that Gaza's civilian population is being used as human-shields. It ignores its now sixteen-year imprisonment of Palestinians in Gaza, and it attempts to dislodge the fate of Gaza from the wider context of the Palestinian anti-colonial struggle by applying a false liberalism that frames this current aggression as a democratic war against terror—what pro-Palestinian activists have satirically called “Hamaslighting.” Within this logic, Israel can commit disproportionate violence against an entire population, including its edifying and cultural institutions, by claiming self-defense and its own cultural preservation.

Alongside the intentional destruction of a healthcare system crucial for Gaza’s survival, in this recent aggression, Israel has destroyed churches, Gaza’s oldest mosque—the Great Omari Mosque, universities and schools, the Orthodox Cultural Centre, Al-Qarara Cultural Museum, and Rafah Museum, which was a self-funded initiative that held school visits for children. (I should add that using cultural centers to host educational workshops on Palestinian cultural history is especially important, as many UNRWA schools run in two daily shifts due to insufficient resources. As such, extra-curricular support is critical for the development of these children’s educational futures.). The wrecking of these cultural and educational sites has lead Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor to describe the latest aggressions as a "campaign against cultural heritage". These acts of destruction are also occurring across several Palestinian cities, including Tulkarem and Jenin where monuments are being removed. Such violent acts directed towards the cultural identity of these cities are an affront to Palestinian self-determination.

New Maps, New History

Although 7 October is certainly not the beginning of Gaza’s history, it is an acceleration of Israel’s policy to take Gaza back to the “Middle Ages.” 7 October also gave birth to a cognitive apartheid between those who recognize what is occurring in Gaza as a genocide and those who deny the genocide by unashamedly endorsing Gaza’s annihilation.

Fearing that the word genocide is becoming mainstreamed amongst those critical of Israel’s actions, last week John Kirby, the White House’s National Security Council’s spokesperson, doing Israeli’s propaganda work, reappropriated the term by calling Hamas a “genocidal terrorist threat,” all the while staying resolutely silent on the massacres of Palestinians. Similarly, the Harvard Law Review denied publication of a Palestinian academic for stating Israel was committing genocide in Gaza. We are at a stage where labelling genocide is worse than committing genocide.

Enabled by linguistic manipulation, and what UN representative of Palestine, Nada Tarbush, recently called “state-sponsored disinformation," Israel and its allies seek to undermine Palestinians legitimate resistance to occupation by rebranding genocide as a moral fight against “human animals.” This dehumanization of Palestinians has facilitated their collective punishment, mirroring previous genocidal rhetoric toward Jews under Nazi Germany who were referred to as vermin or parasites or the reference to Chinese as Shina Pigs during Japan’s invasion in the 1930s.

In this sense, events since 7 October have also reaffirmed what a lot of Palestinians working in the West have feared all along: our mistrust in democratic representation by Western institutions that work to other, silence, and exclude pro-Palestinian voices from mainstream political discourse. These draconian policies enacted on a political, legal, and educational level are now impacting the so-called liberal art world. Artforum editor, David Valesco, was fired for publishing an open letter that called for a ceasefire; a photography biennale in Germany has been cancelled because the organizer’s social media posts were in support of Palestine; and elsewhere Germany’s policing of pro-Palestinian solidarity has led to the resignation of Documenta’s finding committee. Artists, curators, and cultural administrators are being punished for standing with Palestine. The hope is to intimidate critics of Israel into silence. This current distortion of representation recently led Anne Boyer, The New York Times poetry editor, to release this powerful statement in response to the “Israeli state’s US-backed war against the people of Gaza:”

Because our status quo is self-expression, sometimes the most effective mode of protest for artists is to refuse. I can’t write about poetry amidst the ‘reasonable’ tones of those who aim to acclimatize us to this unreasonable suffering. No more ghoulish euphemisms. No more verbally sanitized hellscapes. No more warmongering lies. If this resignation leaves a hole in the news the size of poetry, then that is the true shape of the present.

Boyer’s act of withdrawal is in direct dialogue with what the late Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti identified as the corrosive impact of verbicide; the intentional and deliberate distortion of language to alter truthful representation. In his 2003 essay Verbicide, Barghouti argues that Israel’s verbal and linguistic manipulations can help us understand how genocides happen, but more specifically, how such distortions play a critical role in enabling Israel’s colonial remapping of historic Palestine. As he stated then:

The pollution of language can get no more blatant than in the term West Bank. West of what? Bank of what? The reference here is to the west bank of the River Jordan, not to eastern Palestine. The west bank of a river is a geographical location--not a country, not a homeland.

The battle for language becomes the battle for the land. The destruction of one leads to the destruction of the other. When Palestine disappears as a word it disappears as a state, as a country and as a homeland…..By a single word they redefine an entire nation and delete history. The Israeli occupation imposes a double, triple, endless redefinition of the Palestinian. Call him militant, outlaw, criminal, terrorist, irrelevant, cancer, cockroach, serpent, virus--the list becomes endless. Be the one who makes the definitions. Define! Classify! Demonize! Misinform! Simplify! Stick on the label! Then send in the tanks!

Can verbicide lead to genocide? Oversimplification… might be, as history teaches us, a recipe for fascism. That's why the rhetoric of them/we and either with us or with evil is not just irresponsible jargon--but an act of war.

Today, we have seen how the oversimplified equation of Gaza=Hamas=justification of genocide has directly resulted in shrinking the already compromised territory of Gaza into an even smaller space. Whereas prior to 7 October Gaza was conceived of in its overcrowded entirety, this recent aggression has drawn an even narrower mental map of the Strip. By establishing a split between North and South Gaza early on, Israel’s deceptive military strategy has resulted in the mass exodus of Palestinians who have been forced to leave their homes by foot: a haunting image that mirrors the expulsion of Palestinians from their cities and villages in 1948. As the genocide intensifies, and civilian infrastructure continues to be aggressively targeted, “North Gaza” has become further fragmented into a network of buildings and domestic spaces, including, but not limited to: Al Shifa hospital, the Indonesian hospital, UNRWA schools, and Jabaliya refugee camp: Areas and institutions that are necessary for human survival, which are being wiped out. On the one hand, it gives the false impression that Israel is specifically targeting strategic sites of terror. However, this false re-mapping of public space is designed to spatially reduce Gaza into an incohesive spatial notion of random buildings, and thus, depersonalize it into a gamified site of war rather than a centuries-old, culturally rich urban center.

These disorienting fragmentations have been used by several Israeli politicians to crudely justify ethnic cleansing. Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich said: “I welcome the initiative of the voluntary emigration of Gaza Arabs to countries around the world…This is the right humanitarian solution for the residents of Gaza and the entire region after 75 years of refugees, poverty and danger.” This plan was echoed by the outgoing Israeli ambassador to the UN, Danny Danon, who stated that:

Gaza was not a nice place to live before the war, and it will not be nicer place to live after the war, and…the international community should think about options to offer those who want to move out. And we said it should be a symbolic number that every country will take upon itself to help Palestinians there to have a better life. If you want to move to another country, you can do that. I can do the same. Why not to build that option for some of the people in Gaza who want to move out?

Here, ethnic cleansing genocidists are masquerading as humanitarian solutionists.

Deploying the language of concern and advocating for Palestinians’ free movement, so long as it’s away from Palestinian land, presents a cruel irony especially as these borders are impermeable for things like medical supplies, fuel, and aid. Even if these words were not being spoken by members of the Israeli government, the discourse reduces Gaza to a humanitarian crisis and depoliticizes Palestine by robbing its people of their agency and fight for liberation. Additionally, their words fall in line with the “New Middle East map” Netanyahu raised at the UN merely weeks before the genocide began: an act of blatant cartographic propaganda in which Palestine was completely wiped off the map.

The past fifty days have revealed to us in real time just how quickly Gaza has been re-mapped and re-made in the colonizer’s image.

New Teachers

One of the recurring conversations I keep having with friends and colleagues is that whenever we think things cannot get worse, somehow the situation does. There is an even larger existential question tied to this: how do we teach the future generation about truth, validity, and justice when Israel and its allies continue to act with impunity?

The so-called pause does not leave much room for optimism, but I also do not think we should fall into complete despair. Rather, I turn to Palestinian author Emile Habibi’s satirical term “pessoptimism,” which I would translate as something along the lines of: living with hope alongside inescapable despair even, if it seems somewhat absurd. If I am to be pessoptimistic then, I would direct my focus on the new teachers that we have all collectively relied on during these illogically cruel times. We are all learning from Palestine’s exceptional citizen journalists—Motaz Azaiz, Plestia Alaqa, Hind Khoudary, Bisan Owda, Wael Al-Dahdouh, and others—who have become our guides through this dark period of history. They have educated a new wave of students about the longstanding oppression of Palestinians, hence Israel’s targeting of journalists and ban on international media from entering Gaza.

What is encouraging is how the conversation has moved well beyond a short-term humanitarian discourse to a long-term view of understanding the cruelty of Israel’s settler colonial project. This shift is evident from the videos and infographics being circulated on Instagram and Tik Tok by content creators who are working to educate people about the corrosive effects of disaster capitalism and Zionism. At the same time, these young people are pushing for anti-colonial futures in extremely intelligent, accessible, and exciting ways without diluting the political urgency of the moment. Of course, this is happening off the back of decades-long work by Palestinian thinkers and activists, global movements like Black Lives Matter, and ongoing discourses around repatriation and indigenous rights. Yet, Palestine has undoubtedly accelerated the call for liberation and freedom from oppression for all, everywhere.

We are in a moment where Palestine has truly gone global. We can see it in the placards that carry the watermelon—our long-standing symbol of creative resistance against decades of Israeli censorship—now being adopted globally to resist draconian anti-Palestinian laws by Western governments. And given Israel occupies a unique position—in that its settler-colonial project is funded and upheld by a global state community—perhaps it is why the brutality in Palestine today is, as Richard Seymour argues, ‘reverberating globally’ and leading people to recognize that our global oppressions are linked. In this moment, we should not underplay how our old and new Palestinian teachers have driven a new consciousness centred on global justice.

Amongst all the content that we have consumed, one that resonated with me most was by Palestinian content creator Salma Shawa. In a TikTok video released on the fortieth day of the genocide, she tells the story of a famous Yiddish folk tale called It Could Always be Worse by Margot Zemach. For those of you who have children, you may be aware of the story via Julia Donaldson’s famous adaptation, A Squash and a Squeeze. The story centers on a man who is frustrated by his extremely small living space that he shares with his wife and six kids, leading him to call on a wise Rabbi for a solution. Telling the Rabbi his situation “couldn’t be worse,” he is advised to take in the animals he owns into his living space, which he does, thus making the situation even worse than before. He keeps going back to the Rabbi to complain, and each time the Rabbi responds by telling him to take in more and more animals, until the man can’t take it anymore, and finally tells the Rabbi: “help me, save me, the end of the world has come!…There is no room even to breathe. It’s worse than a nightmare!” Eventually, the Rabbi advises the man to clear his home of his animals, which he does, thereby returning his living situation back to where the story began. The next day, the man ecstatically tells the Rabbi, “you have made life sweet for me. With just my family in the hut, it’s so quiet, so roomy, so peaceful… What a pleasure!”

When I read the Donaldson version of this story to my toddler many months ago, I read it as a moral tale of appreciation and gratitude. However, after hearing Salma Shawa retell the story from the perspective of her Palestinian teacher, it took on a whole new meaning. As she explains, it is a cautionary tale of power and oppression, namely how those in power can thwart the revolutionary ambitions of the oppressed through coercion and control. Read through this critical lens, the story offers a pertinent lesson for understanding the unspeakable horrors we are witnessing in Gaza today. Not only does Israel’s graphic violence trick us into thinking that life before the genocide was desirable for Palestinians, but it also conceals an insidious violence that seeks to derail the idea of a future free Palestine. And yet even in their most dire moments, Palestinians refuse to submit to the parameters set by their oppressors: a reminder that Palestine and its lessons will lead the world towards true justice and freedom.

After the current phase of genocide—whenever it may end—we must never forget that although things have gotten worse than we could have ever imagined, Gaza is still a besieged territory and Palestinians across historic Palestine and in the diaspora continue to be denied access to their land. Even if there is a “pause” in accelerated violence, Israel’s cruel attempts to distort and fracture the land through checkpoints, apartheid walls, slow and accelerated genocide, will continue. As such, in this moment of heightened Palestinian catastrophe, it is more crucial than ever to hold on to the revolutionary ideal: On this land we belong and on this land we will return.

[1] This talk references excerpts from an essay I published in 2014 titled “The Future of Art in an Age of Militarized De-production: Rethinking Cultural Development in Palestine,” during the height of Operation Cast Lead. Much of what I wrote then sadly remains true so have been included in/ adapted for this talk.

[2] Since delivering this talk it has been reported that Rashad al-Shawa cultural centre has been destroyed by Israeli bombardment: https://twitter.com/AlnaouqA/status/1729546776615567717