Atef Shahat Said, Revolution Squared: Tahrir, Political Possibilities, and Counterrevolution in Egypt (Duke University Press, 2024).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Atef Said (AS): In my book, I discuss how many revolutionary actors brought ideas such as El Naddaha (النداهة or “the caller”), a myth or a legend particularly prominent in Egypt’s countryside about a female spirit that calls men to the Nile, leading to their death or disappearance. For me, the call for the revolution was a dangerous temptation. I believed that everything could only be better than the conditions of that time. I could not resist being there. I never imagined that I would be a scholar of a revolution. But on a personal level, like many Egyptians, I was drawn to the revolution and gave it my full energy, emotions, and thoughts. I went through cycles of hope and despair during this journey—it was not easy, but I knew I wanted to write about it.

I coined the notion that the revolution is “lived contingency.” This refers to how revolutionary actors practice and experience the revolution, particularly in terms of the actions they do or do not take in relation to the possibilities, unpredictabilities, and practices of power during its course. I have been enraged with much scholarship on the Egyptian revolution that prematurely proclaimed its success on 11 February 2011, or else claimed its death or that it was doomed to fail from the beginning. My notion of the revolution as lived contingency demonstrates how uncertainties were the rule throughout the events from 2011 until the coup in 2013. Against these analyses, I believed that revolution as lived contingency would be a good lens to explain how these uncertainties were the only certain rules of the revolution. In the book, I argue against presentist and teleological analyses of revolutions, while centering revolutions as large processes of explosions of possibilities and projects of containments, both jam-packed with uncertainties.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

AS: I bring the following fields into conversation in this book: revolutions and social movements, Egypt’s politics and contemporary history, and spatialities and temporalities of contention. Historical sociology of revolutions and ethnography have also been critical to me in this work. The notion of lived contingency speaks to most of these bodies of scholarship. In the book, I have an appendix on how I conducted historical ethnography of revolutions.

In addition to contingency, I analyze the different meanings of being revolutionary in the context of revolution. I present a theorization of counter-revolution that highlights how actors and actions of counter-revolution change in the course of a revolutionary trajectory. I also present a new take on the applicability of Leon Trotsky’s famous formation of dual power during revolutionary crises. I explain that Egypt during the revolutionary crisis in 2011 experienced a triple form of sovereignty on the ground: involving the military, Tahrir revolutionaries, and the popular committees. I show how this form is different from Trotsky’s formula and explain the nuances of practicing power on the ground.

As for topics in the book, I discuss the barricades, the famous Tahrir camp and the larger revolutionary repertoire, and the composition of political space and how it changed from the decade prior to the uprising, through the uprising until the military coup in 2013 and beyond. I examine how social media was critical before and during the uprising in 2011 and until the era of digital repression in the aftermath of the coup. I also provide a critical perspective about the experiment of procedural democracy in Egypt (March 2011 until the coup in 2013), although I describe this as election without democratization in the book, in relation to the counter-revolution and to how revolutionary actors dealt with this experiment, as well as how this relates to the practice of politics in Egypt throughout this period.

One of the central questions I try to answer in the book is: was Tahrir Square a blessing or a curse for the Egyptian revolution, or was it both? To do this, I analyze the history of the square’s centrality of protest in Egypt—before, during, and after the revolution. I show how, in short, Tahrir during the revolution meant centralizing the energy and bringing global attention, while at the same time contributing to eclipsing or drawing attention from other modes of actions that happened outside the square. Of these, I give special attention to the popular committees.

Empirically, the book includes new data on the popular committees, on the demography of the martyrs and injured of the revolution, and on an anatomy of the famous camp at Tahrir during the uprising, specifically with regards to balancing mobilization and survival of the camp. The book also has new data on politics and state paranoia after the coup.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

AS: I have been writing and teaching on revolutions, social movements, and political sociology for a decade—including about the military and the Egyptian revolution, the counter-revolution and Tahrir repertoire, and the Egyptian state, among other things. In a sense, Revolution Squared includes a synthesis of these works, with some original materials—an extension of my writings over the last decade.

In my earlier work, I examined closely the issue of spatialities of political contention in Egypt. In the decade before 2011, I identified a pattern whereby Egyptian activists turned to the space of social media and street politics when formal political space was virtually closed, in order to expand the formal political space and pave a road to democracy in Egypt. The gradual and contested nature of the opening of formal political space resulted in a margin of freedom in street politics. In my new book, I examine how the 2011 revolution disrupted this formula, leading to a collapse of the undemocratic formal political system and a dramatic opening of social media/internet spaces and revolutionary street politics. I also examine how, since the coup, in the context of the complete closure of political spaces, the formula has lost relevance. All three political spaces are closed and almost equally targeted by the Sisi regime. Street protest is forbidden. The formal political space is almost entirely controlled by the military and intelligence apparatuses. And the digital space, once immune to the kinds of repression imposed elsewhere, has been transformed into a polarized, fragmented space policed by the regime. In short, I try to historize the shifts of political space through time.

I used to be a human rights attorney and researcher in Egypt and an affiliated member with revolutionary socialists, until I moved to the United States in 2004. I have written two books about torture in Egypt. My new book also has many insights about the coercive apparatus in Egypt and torture. In this sense, Revolution Squared reflects not only the culmination of my work as a historical and political sociologist, but also my activist history.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

AS: I am hoping that both the scholarly camp and Egypt pro-democracy and change actors read the book. I really hope that it will be part of conversations about studying revolutions and what happened in the Egyptian case. I also hope that many of the Egyptian revolutionary actors read, critique, and reflect upon the ideas in the book. For this audience specifically, I stated in my conclusion that the biggest mistake of Egyptian revolutionaries was not leaving Tahrir on 11 February 2011, or that they trusted the military, but that they did not believe enough in their power. I believe in the power of reflection. We should step up and work on developing counter-narratives about what happened in Egypt in 2011 and in the years that followed, as well as about Egypt’s role in what is happening with the Palestinians and its position in reactionary politics. The readers will see that I am critical of the simplistic fixations on certain events in the revolution and its aftermath. While we analyze certain events and draw lessons from them, we should think of what happened as a whole; self and collective reflection is vital.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

AS: I am working on two concurrent projects; both are expansions of Revolution Squared in different ways. The first project explores the future of revolutions. For me, whether or not there is a future for revolutions is a futile question. Rather, I am interested in the nature of future revolutions as they relate to political and social change, and the evolving meanings and practices of democracy today. The project is theoretical and historical in nature, where I examine the shifting meanings of revolutions historically, in relation to coloniality and decoloniality and knowledge production. I propose that to better understand future revolutions, we must closely examine our past knowledge about revolutions and the newer conditions of revolutions in the second half of the twenty-first century. In my second project, I investigate the global rise of neo-liberal authoritarianism over the past two decades, within historically established democracies and non-democracies alike. I do so with a focus on the expanded role of digital technology in shaping and/or eroding substantive meanings of democracy in relation to the rise of new modes of governance and digital capitalism.

J: It seems that you have a unique positionality that was perhaps critical in shaping how you wrote this book. Can you tell us more about this?

AS: I devoted an entire appendix in the book about my positionality and how it shaped processes of research, data analysis, and writing. In this, I discuss how my positionality is multi-layered and that this fact pulled me in different directions and was constantly shifting. These layers include the fact that I have been an outsider, coming from the United States; that I have been an insider, returning to a familiar context (I grew up and lived in Egypt until 2004 and still maintain my Egyptian citizenship); that I am a scholar, conducting research in pursuit of a degree at a US institution; that I am a former human rights and leftist pro-democracy activist in Egypt who still maintains connections with key activists and activist networks there; and that I was simultaneously a participant in and an observer of the revolution. In short, I would say that my positionality gave me unique accessibility to so many things, but at the same time I have experienced difficult emotional burdens.

Excerpt from the book (from Chapter 2, “Peak of Revolutionary Possibilities - Squared I: How the Revolution Was “Bound” Within Tahrir,” pp. 83-86)

Conclusion: Tahrir as a Revolutionary Boundary

Tahrir’s identification with the revolution was not just a metonymy. It reflected the fact that Tahrir was constituted asphysical and symbolic site of the revolution, that its boundaries became the boundaries of the revolution.

It is useful here to say one word about social boundaries. Boundaries are simply methods of separation, of inclusion and exclusion. Social boundaries entail categorization and identification about who is in and who is out (see, for example, Simmel’s notion of the stranger). I argue that spatial analysis of revolutions and movements should not be limited to how the geographic environment enables or disables protests. We also ought to think of how claim making is, itself, spatial, and how a movement is bounded by a specific network and an idea about specific place(s). Of particular relevance here is Tilly’s idea about spatial claims-making in contentious politics. Tilly argued for two types of contention: contained and transgressive. The latter is the case when claim-making involves new actors and employs innovative means of collective action. Tilly argues the distinction is important “because transgressive contention more often disrupts spatial routines in its setting, and more often involves deliberate occupation, reorganization, or dramatization of public space”. As my research shows, however, Tahrir was an instance of both contained and transgressive contention.

Tahrir was contained in the sense that the most critical pieces in the revolutionary modes of action were associated with Tahrir (the battles to reach Tahrir, after which the police apparatus was defeated, and the sit-in that became the revolution’s camp) and also thusly, the revolution was literally located in and symbolically represented by a relatively contained space in the center of Cairo. But Tahrir also represented a transgressive contentious case insofar as it was constructed as the center of action and mobilization for a nationwide revolution. It was understood as the symbolic seat of a worthy adversary to the Mubarak regime.

Tahrir was made a boundary of the revolution through the discourse on the ground and the actual demarcation of the square through barricades. Over and over again, I heard protestors in Tahrir say things like, “When you enter Tahrir you are in the revolution,” or “You are now in the most important liberated zone in Egypt,” or simply “Welcome to the revolution.” Indeed, some of my interviewees noted that, despite the dangers, they “never felt safer” than when they were in Tahrir. Outside it, they said, they were anxious and worried about the future of the revolution and the future of the country. Inside the square, all their fears and worries ceded importance to the cause of revolution itself.

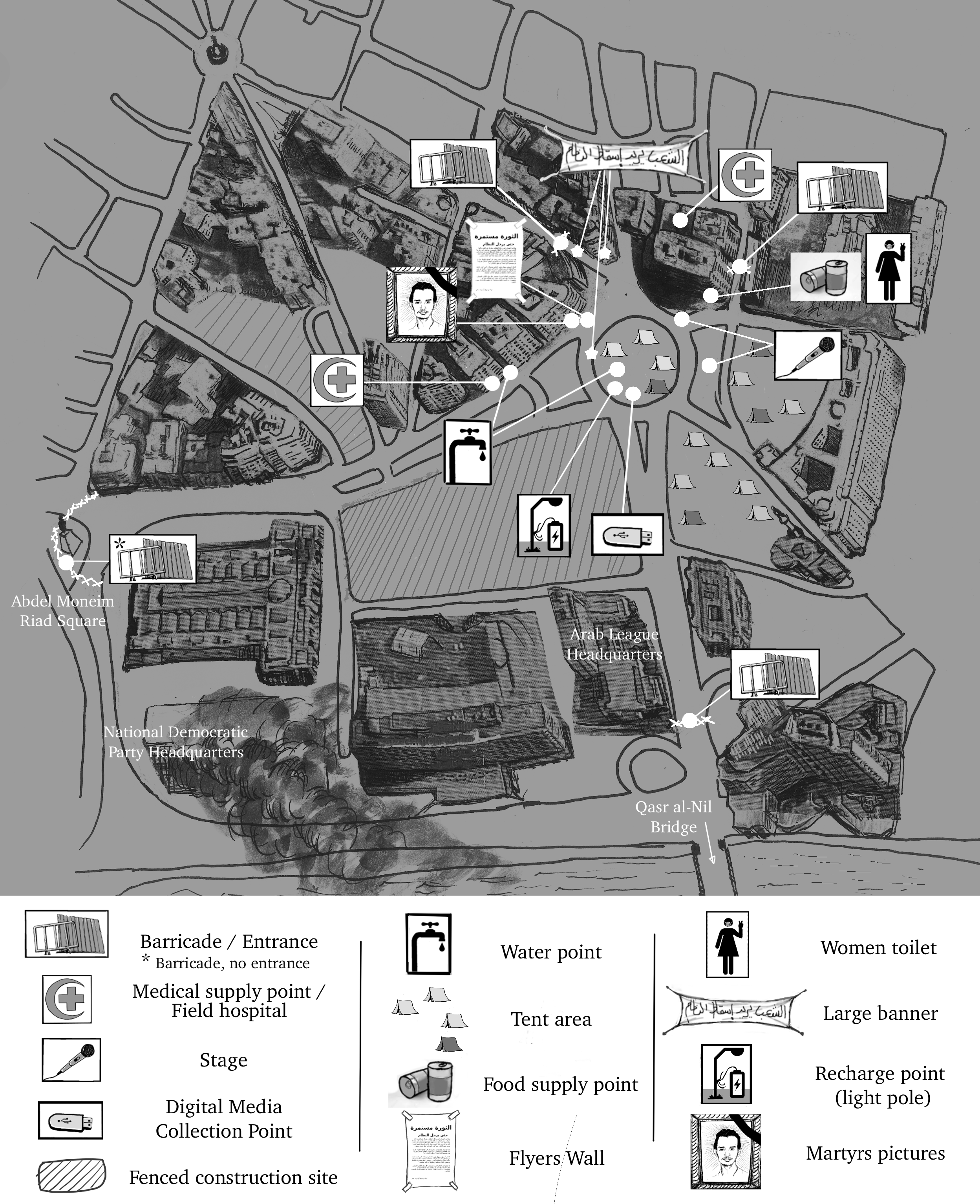

Barricades first appeared the afternoon of January 28, 2011. A leading activist told me, “It was the evacuation by force on January 25 that gave us the idea to erect barricades on January 28, after seizing the square for the second time.” These were still few barricades. But after the camel battle on February 2, 2011, Tahrir was completely surrounded by barricades. Protestors brought tires, broken trees, rocks, traffic barriers, and constructed these barricades. Map 2.03shows the spread of the barricades, the location of tents in the famous camp, as well as key banners that carried the revolution’s demands in Tahrir during the uprising.

Layout of Tahrir’s revolutionary camp on Feb 11, 2011 (reconstructed) by Rime Naguib

During a revolution, I argue, barricades not only divide physical space and indicate control, they assert the authority to control and separate zones. Barricades, in revolutionary times, are associated with liberated zones and alternative authorities. In my research, I show how protestors erected barricades to protect their republic in Tahrir Square from intruders, going so far as to establish checkpoints and inspect visitors. I argue any satisfactory analysis of revolution should include an analysis of the composition and the distributions of barricades, whether or not check-points were associated with these.

But beyond suggesting that barricades still matter in revolutions, I also argue that barricades’ usage varies such that there were three critical differences between barricades in Tahrir and barricades elsewhere during the Egyptian Revolution. The first is that barricades in Tahrir were established after brutal confrontations. The second relates to the difference between the rhythm of the barricades in Tahrir as compared to the barricades elsewhere (especially the popular committees I will discuss in Chapter 3): barricades in Tahrir were busy, with people coming and going all the time, and inspections continuing apace. The action did not stop in Tahrir until the day Mubarak was ousted, while barricades erected by the committees saw just a few days of intensity, from the night of January 28 until roughly February 3. Third, the materials that constituted barricades differed: protestors in Tahrir used traffic barriers and fences seized from construction sites, but also extended their barricades to include the burned-out police trucks and armored vehicles near Tahrir’s entrances. These objects gave the square and its entrances added symbolic power, marking their locations as the site of the victorious party on January 28. The barricades enclosing Tahrir thus came to serve as symbols of the division between revolutionary and non-revolutionary space, demarcations of the square, both literally and figuratively, as something that protestors controlled.

Speaking of the barricades in relation to the Tahrir camp, it is useful here to correct a common confusion about the larger revolutionary repertoire. Many observers reduced the larger revolutionary repertoire to the camp in Tahrir. I define Tahrir repertoire, or the larger revolutionary repertoire, as a set of available means, which included the occupation of public space, the formation of a mini-republic that required the presence of many forms of organizations, the social media focus on Tahrir, and erecting barricades to police the space and protect this republic, as well as the presence of marches and rallies that ended in Tahrir Square. protest in Tahrir and encampment in the square, was inspired by past protests in Tahrir. But the larger combination of all these means of action was invented during the revolution in 2011. But many of the important pieces that made the revolutionary repertoire successful the first time were missing during attempts to repeat the revolutionary repertoire in the aftermath of the uprising.

I also argue that the creation of a revolutionary boundary in Tahrir did not start in 2011. Rather, a diverse yet specific set of historical conditions constituted Tahrir as the center of the revolution. These conditions included its historicalsignificance and political prominence, both of which made it a target for protest, as well as the regime’s attempts to limit mobilization to Tahrir and paradoxical endorsement of Tahrir as its central counterpart; the media’s obsession with Tahrir; and the reliance of the revolution on the continuation of the sit-in in Tahrir. Together, these conditions created a convergence of processes that made Tahrir the most powerful center of gravity of the Egyptian Revolution, the pivot point around which a revolutionary boundary was established. Indeed, because Tahrir Square became metonymic with the revolution, so many artistic compositions were created during the uprising by revolutionary actors and artists that carry this meaning, in forms of songs, graffiti and poetry. The epigraph mentioned earlier in this chapter is part of a song by famous female singer Aida el Ayoubi. It was composed and widely circulated after ousting Mubarak.

Of course, the very idea of Tahrir becoming the center of the revolution means that there existed other revolutionary modes of action and perhaps important possibilities—alternately beyond or even within Tahrir—that were not central; voices, modes of action, and forms of political imagination that, unlike Tahrir, did not come to be understood as the revolution, but remained on the margins of the revolution.