Jörg Gertel, David Kreuer, and Friederike Stolleis (eds.), The Dispossessed Generation. Youth in the Middle East and North Africa (Saqi Books, 2024).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you edit this book?

Jörg Gertel, David Kreuer, and Friederike Stolleis (JG, DK & FS): The Arab uprisings of the early 2010s raised hopes for the development of more democratic structures and better living conditions for millions in the region. But shortly after the upheavals and revolutions authoritarian backlashes followed, new civil wars broke out, national and local economies collapsed, while food and energy insecurity expanded.

At the beginning of the 2020s several of these crises converged, displaying varying temporalities: long-term processes such as impoverishment, precarization, and environmental degradation combined with short-term dynamics such as new outbreaks of violence and pandemic threats. These processes reinforced each other and were often almost irreversible.

In this time of interlocking crises, young people in the MENA region are systematically deprived of fair opportunities in life. This book explores how and why this has become so bad that we refer to these young people as a “dispossessed generation.” Dispossession, we argue, is the gap between “what is” and “what could be”; they are drifting further and further apart.

The study is based on a standardized survey of twelve thousand people aged sixteen to thirty in 2021, as well as over two hundred narrative interviews during late summer 2022, conducted in Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan, Tunisia, Yemen, and among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. By reporting the views and experiences of young people, we hope to give a voice to this generation, which has not lost all hope despite the dire circumstances they find themselves in.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

JG, DK & FS: Our book starts by opening up the understanding of dispossession. It focuses on both capabilities and aspirations. Capabilities capture the access to resources and the considerations of freedom, social justice, as well as opportunities to live a life in dignity, while aspirations address the interplay of desires, ambitions, and personal goals with fears, stress, and depression. The analysis of these ambivalent processes that the young generation is exposed to frames the study and runs like a common thread through all the chapters of this book. We recurrently discuss results by country, but also point out wider regional patterns where these exist, such as in relation to lifestyle preferences or the social strata young people find themselves in.

Three consecutive book sections focus on the different crises, the facets of everyday life, and societal actions. The conjunction of crises we investigate ranges from structural economic problems, including dramatic rates of youth unemployment, to the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. We also analyze the impact of hunger and violence, the ever more frequent environmental crises, as well as the (forced) mobility of young migrants and refugees. The next section addresses the everyday lives of young people. These chapters offer insights into changing family, education, and gender roles, discuss the development of lifestyles, and analyze the meaning of values for different groups, as well as the role of religion. Finally, the authors scrutinize societal actions and engagement of young people. Here, the chapter addresses communication patterns, attitudes towards politics and political mobilization, the range of civic engagement, and, finally, the hopes and expectations with which young men and women look to their own future and that of their societies. Methodologically, we combine quantitative and qualitative analysis to offer a combination of detailed personal accounts and nuanced pictures of structural developments.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

JG, DK & FS: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung’s first MENA Youth Study, published also by Saqi Books in 2018 under the title Coping with Uncertainty: Youth in the Middle East and North Africa, addressed the interplay between insecurity and uncertainty in the everyday life of young people. The aim was to investigate the vulnerability of young people in the MENA region five years after the Arab Spring with a focus on different groups and different countries.

While insecurity, as we argued, relates to the present and arises largely from the lack of access to resources, uncertainty relates to the future. The strategies used to cope with uncertainties are varied, based on differing contexts, faiths, and knowledges, and are also always resource dependent—the resource dependent ability to act thus connects both insecurity and uncertainty. However, due to the drastic change in social conditions, even proven coping strategies are often no longer effective: both insecurity and uncertainty are expanding.

The increasing impoverishment, understood as cumulative deprivation, and the withdrawal of life opportunities have continued over the past five years; they have not been reversed or mitigated, but have rather been consolidated and deepened in the wake of environmental degradation, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the Ukraine war causing downstream food insecurity in the region.

Using the available data from two time slices—2016/2017 and 2021/2022—we are able, for the first time, to track developments and to analyze the dynamics of dispossession affecting young people in the MENA region. This is possible since many questions of the survey were repeated. We also selectively extended the time period in question (back to 2010/11) in order to understand the long-term development of certain aspects by using retrospective questions.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

JG, DK & FS: We appeal to an interested general public, as the texts tend to be light on theory and jargon, but rich in quotes and anecdotes from the young people themselves, as well as many graphs that illustrate the findings. In addition to the English version, the book has been out in German and is about to be published in Arabic as well! This should make it accessible to students and researchers, civil society actors, and decision-makers in the MENA region.

In the region, the aim will be to enter into dialogue with young adults and other decision-makers and multipliers in order to present and discuss the findings of the study and to provide space for developing strategies for societal engagement and participation to counter the dynamics of dispossession. However, as the causes of dispossession are far from solely being home-made or local—they have historical dimensions and are determined by external interests and interdependencies—it is hence also a matter of raising awareness in Europe and elsewhere.

Beyond the MENA region, this study may help to inform interested individuals about the diversity and complexity of young people’s challenges and recent dynamics. It is also crucial for designing interventions and projects to mitigate the precarious situation of young people and their urgent needs. This includes encouraging political decision-makers, but also business people and development experts to empower these young people and their visions for our common future. Our study findings do not offer simplistic explanations or solutions, but may stimulate serious debates and initiate more detailed local case studies.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

JG, DK & FS: We are currently coordinating the upcoming Routledge Handbook: Youth in the Mediterranean, where we expand the perspective to include the countries north of the Mediterranean. This will bring together dozens of experts from a range of disciplines and is a very exciting project.

For more information on The Dispossessed Generation. Youth in the Middle East and North Africa please consult the FES MENA Youth Study project website here.

Excerpt from the book (from Chapter 4: The Covid-19 Pandemic, pages 93 to 98)

Lessons learned from the pandemic

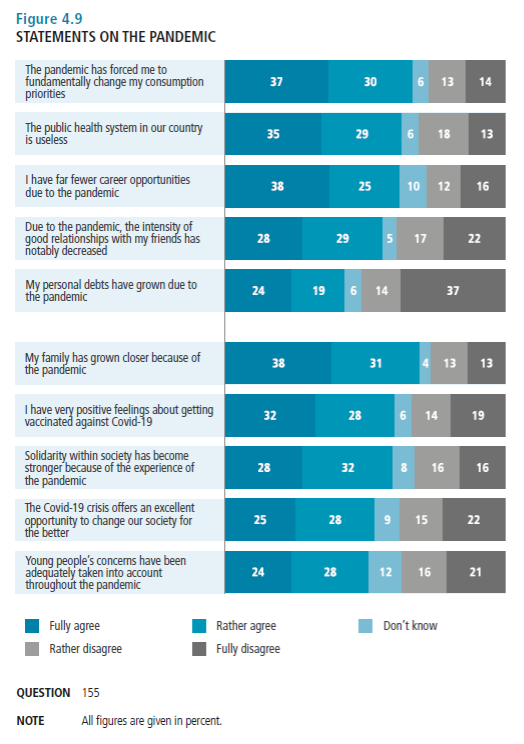

The ambiguity of how Covid-19 was experienced by the adolescents and young adults surveyed is also reflected in the fact that the majority of respondents across the region affirmed both negative and positive statements (Figure 4.9).

On the one hand, two in three respondents had to restrict or adjust their spending behaviour, while an equally large proportion reported stronger family ties. This section summarises what lessons can be learned from the crisis as seen from the perspective of the younger generation in the MENA region. What must be borne in mind here is that the pandemic appeared to have peaked at the time of the survey, although the virus was still circulating.

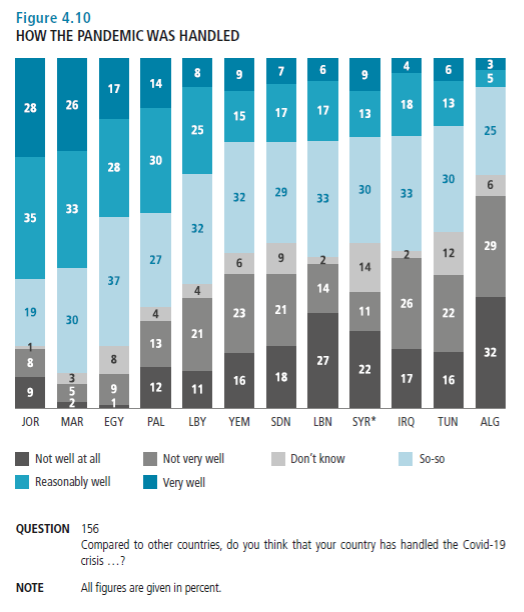

The evaluation of the responses on how governments handled the pandemic shows that young people’s opinions differ widely (Figure 4.10). There is a strong sense of dissatisfaction in Algeria, but also in Lebanon and Iraq – countries in which the governments are already facing legitimacy crises for a number of reasons. By contrast, respondents in the monarchies of Jordan and Morocco are quite satisfied with their countries’ national corona policy; similarly, very few dissenting voices can be heard from the young people from Egypt either, governed as it is by a repressive regime.

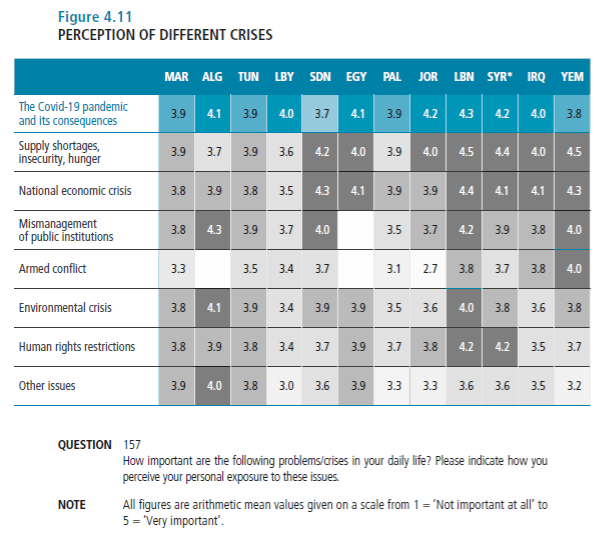

At the same time, it is worth noting that respondents’ perceptions of the pandemic and the government’s handling of it are also impacted by other ongoing crises. To explore this connection more closely, the young respondents were asked how important the Covid-19 pandemic was in their everyday lives compared to other crises (Figure 4.11). In six of the twelve survey groups, Covid-19 ranks first, in some cases on a par with other crises; in the remaining six, other problems are often seen as even more urgent and more serious. The main problem cited by the respondents, especially those in Yemen and Lebanon, is the supply situation (Chapter 6). Another problem frequently mentioned was the economic crisis in the respective country, something that young people in Lebanon, Sudan and again in Yemen perceive as particularly burdensome.

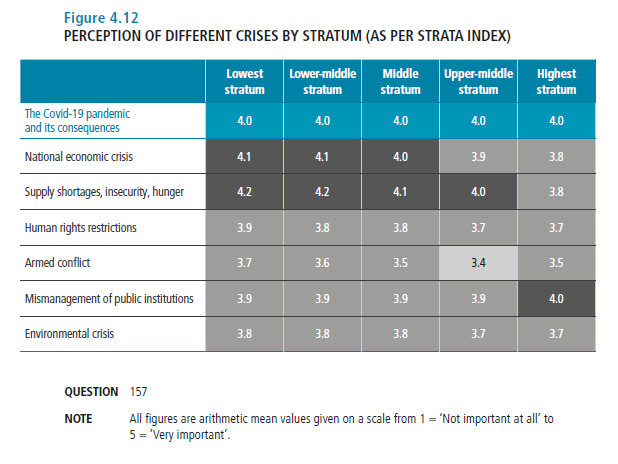

If the results are differentiated by strata throughout all the countries studied, the following picture emerges (Figure 4.12): on average, the pandemic is rated as equally important by members of all social strata, as is the mismanagement of public institutions and the environmental crisis. For many other issues, however, the perceived urgency increases, the lower the respondent’s social stratum. It seems as plausible as it is tragic that vulnerable groups are hit disproportionately hard by many crises. In other words, young people in the lower strata suffer more from other crises, meaning the coronavirus pandemic seems to be less significant for them in relative terms, although in absolute terms, it is just as pressing as for the higher strata.

As Figure 4.9 shows, however, many young people in the MENA region believe that the experience of the pandemic also offers opportunities and a ray of hope. Many families have come closer together, solidarity in society has increased and the crisis may also be a good opportunity to change society for the better, the respondents state. This confidence is expressed by 19-year-old student Aya from Tripoli (Libya), for example:

The pandemic has had a positive impact on my life. During quarantine, I had the opportunity to discover many things that I didn’t know before.

Batool and Lobna from Jordan and Morocco, respectively, are convinced that online studying has its advantages, even if they immediately think of negative aspects a few sentences later – the pandemic remains a double-edged sword even for the most optimistic of young people:

The pandemic had a positive impact on my life. I’m a student and I work at the same time so thanks to the distance learning programme I was able to continue waitressing in a restaurant without any problems. The pandemic also meant I was able to see my family more often. On a family level, though, we were negatively affected because my brother, who supported the family financially, was made redundant during the pandemic. After that, my sisters and I contributed to the family’s income (Batool, 24, Jordan).

Many people have complained about the pandemic, but I really enjoyed it. Everyone was at home and there was no noise. I’m someone who likes to be at home and doesn’t go out often. I had a lot of time during the pandemic, especially when it came to online lessons. I actually prefer digital learning because it allows me to develop from different angles, plus it freed up the time we would otherwise have spent commuting. On the whole, the pandemic hasn’t affected my decisions, apart from the compulsory vaccination. I was really against it, but I was forced to get vaccinated (Lobna, 22, Morocco).

Perhaps the biggest positive surprise during the first phase of the pandemic, however, was the extensive, spontaneous, often self-organised, solidarity-driven civic engagement seen among large sections of the younger generation (Chapters 15 and 16), with many getting involved in awareness campaigns, for example, as was the case with 26-year-old Yemeni Bushra:

When the pandemic broke out, we carried out awareness campaigns and health and community training using our own resources. We went into people’s homes to raise awareness and we gave them advice on how to protect themselves from the virus. We told them how important it was to wear a mask or to stay at home and only leave the house in absolute emergencies.

Another focus was on providing for people in need in their respective communities, which was mentioned in many of the interviews – for instance by Sami from Morocco, Wafa from Palestine, Ali, a Syrian refugee from Lebanon, and Slim from Tunisia. As the pandemic progressed, more and more educational initiatives and self-help groups sprung up:

We have seen an impressive level of mobilisation in our community, not so much in the beginning, but then a lot of people started to take action online. I personally coordinated three or four online sessions with the Tamazigh women’s movement, one of which was on humanitarian issues, the other on mental health and the use of art as a means of expression during lockdown (Ines, 24, Libya).

We set up a self-help group for psychological and social support. There were hotlines that women who had been abused could call. A call centre that provided support to women who had been the victims of violence or children with special needs and people with problems in general. We managed to help many of these women, men and children (Nahla, 26, Morocco).

In many of the interviews there was a sense that this engagement would continue after the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, as explained by Wafa, a 30-year-old employee from Majdal Bani Fadil in the West Bank (Palestine):

Of course, this engagement will continue and there will also be more communication after the pandemic. The pandemic has shown that many people need help. So far, we have distributed bread to the local community, held remedial courses for struggling pupils, helped elderly people, entertaining them and lifting their spirits simply by sitting down and talking to them.

Twenty-six-year-old Sami from Syria, who works as a volunteer for a non-governmental organisation in the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon, where he now provides legal advice to Syrian refugees on matters such as ‘registering marriages, divorces and births’ instead of working on health-related issues, has a similar view. His compatriot Ali, who is doing a master’s degree in Aley (Lebanon), is also confident: ‘I will continue with my involvement in civic activities.’

In conclusion, for young people in the Middle East and North Africa, the Covid-19 pandemic was a far-reaching and deeply ambivalent experience. Severe, even fatal illness coupled with measures to contain the virus that drastically changed the daily routines of almost all of our interviewees, sometimes jeopardising their livelihoods, but even more so their mental health. Women were affected to an above-average extent. In combination with the numerous other crises that plague the countries in the region, Covid-19 has thus often proved to be an accelerator of the dispossession of young people, whose educational and career paths were also interrupted in many cases. On the other hand, family cohesion was often strengthened and unprecedented initiatives for mutual assistance and solidarity sprung up among the population, with young people in particular devoting a great deal of time and energy to these activities. Some even managed to carry this positive energy into the post-pandemic period.