Archiving the Past in Times of Change

“When did you arrive?” and “Will you return?” are questions long embedded in the everyday conversations of Gulf residents, both new and old. These questions, often seen as bookending a residents’ trajectory, take on new meaning as growing number of older residents and shifting visa regimes and policy reforms unsettle the once presumed link between retirement and return.

Retirement has historically offered the latter question a definitive answer. Among middle-income migrant families, retirement has traditionally meant departure, a return to the “home country” after years of residence and labour. The end of work marked the end of renewable residencies, a loss of income, and the beginning of a life stage lived elsewhere. For many first-generation ‘oil boom’ migrants who arrived in the 1970s and 1980s, now approaching or already in retirement, remittances and planning centred on futures outside the Gulf, signalling that ‘aging in place’ was never integral to the migration trajectory or imaginary in this region.

Yet demographic data across the Gulf complicate tropes of migration as perpetually youthful and transient. Older non-citizen residents now comprise a notable segment of the population: nearly half of Qatar’s residents aged 75 and above are non-citizens; and in Kuwait, it’s over a third. Meanwhile, younger generations increasingly express a desire to remain beyond their working years. A 2020 survey found that 70% of UAE residents hoped to retire in the country, though many also reported being financially unprepared and anticipated working past retirement age.

Amid these demographic shifts, we see in places like the UAE the introduction of longer-term visas, such as the golden visa and retiree visa schemes, alongside selective pathways to citizenship and voluntary pension schemes, all of which signal the permeability of permanence and the open-ended nature of the question of ‘retirement return’. The golden visa, introduced in 2019, offers 5- or 10-year renewable residency to select groups such as investors, property owners (with assets worth AED 2 million or more), students, teachers, and frontline workers. It enables holders to live, work, and study in the UAE without a national sponsor and includes the right to sponsor family members.

The retiree visa, launched in 2020 in Dubai, and expanded to UAE level in 2024, offers 5-year renewable residency to those aged 55 and over who meet specific financial criteria, such as property ownership, savings, a minimum monthly income, and private health insurance. Both visas mark a departure from employer-linked sponsorship, allowing residents to prolong their stay beyond working years, though both remain closely tied to financial self-sufficiency.

These shifts produce stark juxtapositions. On the one hand, the UAE, particularly Dubai, is actively courting international retirees, viewing their financial capital as a resource for economic diversification. The city promotes itself as a premier destination for affluent retirees seeking lifestyle or amenity-led migration, where leisure, security, healthcare, and comfort are central aspirations. Some of these retirees arrive independently; others follow their adult children, entering under golden visa schemes or as dependents of financially secure younger, family members who work in the UAE. This emerging group is increasingly visible in elder care services and community initiatives tailored to older adults. At the same time, many low to middle-income long-term residents approaching retirement in the UAE face an uncertain future, marked by financial concerns, both in the UAE and their home countries. The result is a widening gap between the aspirational retirement narratives marketed to the financially self-sufficient and the lived realities of multigenerational families navigating retirement with limited resources.

It is within this shifting landscape that my research explores the ‘afterlives of retirement’ among middle-income families who have spent most, if not all, of their working lives in the UAE and whose families now span two or three generations. I focus on the emotional and material impacts of retirement not only on those retiring but also on their adult children, many of whom were born and raised in the UAE. I examine how decisions related to relocation, caregiving, finances, and residency are managed, and how ideas of home and return are negotiated at a collective level within migrant families. Overall, a key question drives this research-what does it mean to grow old in this context?- a question that is conspicuously absent both in policy and in the academic literature on migration in the wider Gulf region.

This research grew out of earlier work I began in 2013 with young adults born and raised in the UAE, initially focused on how they made sense of home, belonging, and imagined futures. As I followed their lives over time, our conversations gradually shifted to include their aging parents and the growing uncertainties around retirement. What emerged was a more intergenerational story, one in which decisions about staying or leaving were deeply entangled with the retirement planning, or lack thereof, of an older generation, who, in turn, often based their decisions on their children’s future plans. Aging and retirement, I came to see, are not individual concerns but a ‘family matter’ in this context.

As life trajectories unfold and retirement and settlement policies in the UAE continue to shift, documenting the experiences of aging among long-term migrant families becomes increasingly urgent. These accounts raise critical questions often overlooked in migration scholarship on the Gulf: Who is able, and who chooses, to age in place? Who has alternatives, and what are the emotional or material costs of those options?

Multigenerational Ruminations around Aging and Retirement

For many long-term residents in the UAE and across the Gulf, the idea of "returning home" after retirement is far from straightforward. This is especially the case for those with children and grandchildren still residing in the UAE. In many cases, younger family members, often UAE-born, act as legal anchors, enabling aging parents to remain through their employment-linked residencies or by financially supporting them if they return to countries lacking robust social security systems. However, many who have the option to stay face a high cost of living and expensive health insurance premiums after retirement age, leading many to have to return. Whether adult children stay in the UAE or leave for work, education, or long-term settlement also shapes older generations’ retirement decisions. Often, family unity is the strongest anchor to the UAE. And when parents rely on their children’s sponsorship, a decision to leave may leave no option but to return ‘home’.

At the heart of these considerations lies a deeply human need: the desire to remain close to loved ones while growing older. My research shows, proximity to family, connection to a familiar place, and aging in an environment that feels like home are central to how many envision a good life in later years.

This is not to suggest that all long-term residents wish to remain in the UAE after retirement. For some, return represents a long-anticipated opportunity for rest and reconnection with a homeland and families left behind decades ago. Instead, I draw attention to options, choices, and the degree of volition in retirement decisions, including the prospect of return. For those who have already returned, other challenges may arise, such as how to maintain ties to the Gulf where children continue to live and how to manage finances. These include navigating visa applications, re-entry, and duration of stay, as well as access to old age benefits and care in countries of origin. For those from war-torn countries, return is often not a viable option. For example, Syrians who reached retirement age during the war have faced particularly complex circumstances, especially those without a plan B, such as property, investments, stable jobs, working-age children to help extend their visas, or a second passport to fall back on. From 2020 onwards, some of these families were able to prolong their visas thanks to golden visas, such as doctors and other frontline workers who were granted these visas during the pandemic, or those who switched to sponsorship by their children who had acquired golden visas. My research highlights how families with limited options and resources develop strategies for retirement and old age.

Family circumstances, shaped by health, death, employment, education, or onward migration, continuously reconfigure retirement decisions in ways that defy linear or individual planning. It is these everyday negotiations and long-term strategies that my research seeks to capture, particularly how notions of home and return take on new meaning at the threshold of retirement.

Less visible in popular discourses, forms of internal relocation within the UAE and transnational aging reveal alternative trajectories of retirement that further complicate the idea of return, and the fact that aging and migration are increasingly entangled in the Gulf.

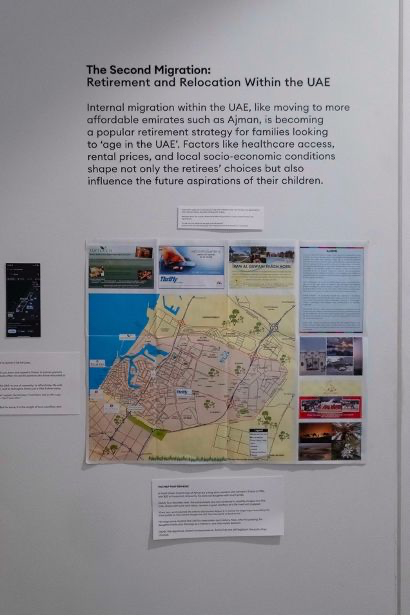

From İdil Akıncı’s public programme Afterlives of Retirement: A Multigenerational Archive of Aging and Migration. Pictured: a hand-drawn tourist map of Ajman, created by a long-term resident who arrived in Dubai in 1980 and has since passed away. As families today move between emirates for work, education, and caregiving, digital maps have replaced paper ones, shaping new forms of home-making that stretch across Sharjah, Ajman, Dubai, and beyond. Yet this map endures as a quiet relic of a time before GPS, and as a tribute to the many residents who helped build the UAE’s infrastructure, lovingly preserved and shared by the mapmaker’s daughter.

Internal Relocation: A Second Migration

For many long-term residents, remaining in high-cost cities like Dubai after retirement is financially unfeasible. In response, internal relocation, moving to more affordable emirates such as Sharjah, Ajman, or Ras Al Khaimah, has become a practical strategy. This internal migration challenge dominant notions of “onward” or “stepwise” migration, concepts traditionally associated with Gulf migrants moving through the region en route to Europe or North America for long-term security. Here, the movement is within national borders, driven by economic necessity and family proximity rather than global mobility.

For some, internal relocation is not merely a cost-saving measure, it is a response to a deeper structural dilemma: the absence of a viable return. Many migrants come from countries affected by political instability, protracted conflict, war or economic crisis, or find that conditions in their countries of origin have deteriorated by the time they reach retirement age. In such contexts, return may be not only unappealing but also unsafe or outright impossible. Elsewhere, the absence of reliable healthcare, social security systems as well as family and community support makes aging in one’s country of origin both financially and physically untenable. At the same time, remaining without sufficient income is increasingly difficult. In response, older migrants turn to a range of strategies to remain: applying for golden visas, establishing small businesses, continuing to work past retirement, or being sponsored by adult children. Relocating to a less expensive emirate allows these limited resources to stretch further and creates a more sustainable path to aging in place.

Real estate companies have begun marketing emirates like Ras Al Khaimah as retirement-friendly destinations for global retirees, especially following the introduction of retiree visas. Yet long-term residents have long engaged in what I call a “second migration,” as a means to remain close to loved ones, extend their savings, and avoid the emotional and social isolation that often accompanies return. For adult children, particularly those in middle-income professions, these relocations are also a way to ensure aging parents can remain nearby, preserving a sense of continuity and care in later life.

Transnational Aging

A second dynamic is that of transnational aging, where retirees divide their time between the UAE, their country of origin, and other places where their adult children have migrated. Some maintain their UAE residency through periodic visits; others return on tourist visas to provide care for grandchildren or to remain connected to a place they still consider home.

This pattern mirrors transnational aging trajectories observed in Europe. There, the idea of a definitive return once shaped the experiences of guest workers, many of whom migrated from countries like Turkey in the 1960s and 70s to fill labour shortages. But over time, that narrative eroded as families settled across generations, and the so-called temporary destinations became places where people aged, raised children, and built lives.

Studies from Europe show how, as time passed, older migrants often aged “in between,” negotiating fragmented family geographies, residency rules and access to care and pensions. For many, the notion of a definitive return became a myth. This complexity is amplified for their children and grandchildren, born and raised in Europe, for whom the idea of return holds little coherence, they were never migrants to begin with.

Similar dynamics are unfolding in the Gulf. As the first generation reaches retirement age, the UAE is now home to multiple generations of residents, many of whom have no country to “return” to. For many, their attachments are rooted in the UAE, and futures often by the search for permanence.

A still from the 1987 Turkish film Kesin Dönüş (“Definitive Return”). A short excerpt from the movie was screened as part of the “Afterlives of Retirement: A Multigenerational Archive of Aging and Migration” public programme. In 1980s Turkey, kesin dönüş became a powerful concept in popular discourse and cultural products, reflecting the hopes of migrant workers returning home after years abroad. The film follows a Turkish family in the Netherlands, tracing how the idea of return evolves from a concrete plan to a complex emotional journey and a narrative shaped by generational shifts, reunions, and loss of life. It speaks to a shared human experience of being caught between multiple worlds.

Property Ownership As an Investment to Permanence

For descendants of the first generation, now in their 30s, 40s, and even 50s, the idea of return is often implausible. While some may have moved abroad for study, work, or citizenship, their sense of home remains tied to the UAE. In fact, several return after years abroad, seeking familiarity, community, and the lifestyle.

Yet the prospect of retiring in place is not straightforward. Media reports estimate the annual cost of retirement in the UAE at AED 240,000-expected to nearly double by 2045. On online forums like Reddit, UAE residents frequently ask: Is Dubai a city for retirees? How do you afford it? How do you plan for your or your parents’ retirement?

Like elsewhere, property ownership is marketed as a key asset for retirement planning. But in the UAE, it also signals residential security in a context where permanency is not guaranteed. For many UAE-born residents, getting on the property ladder, something rarely pursued by their parents who typically rented until they left, has become both a financial and emotional milestone. For some, it is seen as a tangible commitment to the only home they have ever known, and a way to say: we’re here to stay and invest, signalling to a subtle, but powerful narrative change across generations.

This desire, however, collides with a rapidly overheated property market. Since the pandemic, real estate prices have soared, fuelled by international capital flows and Dubai’s growing appeal as a global lifestyle destination.

Recent reforms, like the voluntary end-of-service scheme and more affordable housing and healthcare for senior residents, signal for more options for planning a future in the UAE. But the emphasise on individual responsibility for retirement security remain. Furthermore, in retirement planning, property ownership is ideally one that generates passive income rather than being occupied, which requires alternative investments.

A still from the public programme Afterlives of Retirement: A Multigenerational Archive of Aging and Migration. In the background, two retirees share a final dance in their UAE home before returning to India, moving to the same song, Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow, that they danced to as a young couple upon arriving in the 1970s. Nearly fifty years on, younger generations take to online platforms to reflect on retirement, looking for advise on retirement planning for themselves and their parents, indicating a surge in desire to remain in the UAE in later life.

Why Does Thinking about Aging and Retirement in the Context of Gulf Migration Matter Now?

For many families now spanning generations in the Gulf, the traditional binaries of “home” and “host” countries no longer hold. Retirement, too, no longer signals a straightforward return decision. For long-term residents, return is not always a physical departure but, as Walsh and Näre (2016) note, “a key idea, event, or concept” through which belonging is continually negotiated, regardless of whether return ever occurs or is even feasible.

These trends compel a rethinking of how we conceptualise migration to the Gulf. The growing visibility of retirees and retirement aspirations among long-term residents in the UAE further unsettles dominant portrayals of the region as a space of youth and transience.

Yet despite these realities, migration and aging are still dealt with as separate demographic realities: migration as temporary; aging, as sedentary. In practice, however, we see extended presence, intergenerational care, and emotional investments in place. As migrants remain beyond retirement, via internal relocation, intergenerational sponsorship, continued working years or cross-border ties, they reshape the meaning of home and challenge the assumption that life after retirement and aging inevitably happens elsewhere. Aging thus becomes a crucial lens for understanding the quiet, sustained processes of belonging that unfold beneath formal regimes of temporary migration.

With increasing life expectancy and a growing older population, the question "Where will I grow old?" becomes not only logistical but existential. Needs, attachments, and constraints subtly shape these decisions, influencing not just outcomes but also the terms on which choices are made or postponed. Much of this is grounded in the way migration discourse and governance contour the way we are ought to relate to work and place. Once the employment contract ends, what persists? How do attachments to place endure beyond formal labour?

For some of long-term residents, the desire to remain increasingly extends into the afterlife. Some envision not only aging in the UAE but being laid to rest there, a difficult and often unspoken aspect of growing old. This quiet yet profound aspiration challenges dominant narratives of temporariness, revealing enduring attachments that span both life and death. To wish for one’s final resting place to be near family and in the city one lived and worked in expresses a claim to belonging that transcends legal status, a desire to remain part of a social world, even in absence.

As policies governing aging and migration shift, this research offers an archive of how retirement has been experienced and imagined by first-generation migrants and their children in the post-oil boom era. Rather than treating this moment in UAE migration history as fixed or final, these narratives illuminate how past experiences can inform future challenges, particularly as aging becomes a growing reality in a region long imagined as transient. They also reveal how experiences of aging and retirement are continually reassembled and reinterpreted, whether by different groups living through the same moment or by the same communities across generations.

"I hope I can grow old in Dubai". One of many notes left by visitors who visited the public programme.

[Disclaimer: As part of a multi-phase project on aging and retirement in the UAE and to mark this growing interest in the subject, I recently held a public programme at AlSerkal Arts Foundation in Dubai (13 April 2025) titled Afterlives of Retirement: A Multigenerational Archive of Aging and Migration. It featured media content on aging and retirement, photography, audio and video material from a decade long ethnographic work that document how migrant families in the UAE negotiate questions of aging and retirement. Some of the images accompanying this article are drawn from that programme, which seeks to honour the multigenerational life histories that shape aspirations and experiences of retirement in the UAE.]