I

Although today Muzaffar al-Nawwab (1931/4–2022) is perhaps best remembered across the Arab world for his scathing critiques of Arab and Western leaders and his unwavering support for the Palestinian cause, it was not until after 1969 that he began writing poetry in Standard Arabic that addressed broader Arab issues. In Iraq, he remains cherished for his poems written in the Iraqi dialect, which center on Iraq’s struggle for liberation from colonial domination and feudal oppression. As a committed member of the Communist Party, his main concern was the improvement of living standards and working conditions for the fellahin (peasant farmers) and the country’s poorest communities and it was for this reason that he strongly supported the Agrarian Reform of September 1958, introduced by Abd al-Karim Qasim. The reform sought to address the fact that most of the arable land was concentrated in the hands of large landowners who, particularly in southern Iraq, forced the fellahin to work under harsh and exploitative conditions, claiming the lion’s share of the harvest for themselves.[1] In response, parts of the land were intended to be redistributed, especially to families with little means. However, due to an insufficient bureaucratic capacity, a shortage of qualified personnel, and lack of equipment, these plans could not be implemented immediately. Consequently, the communists—who enjoyed strong support among the peasantry—urged the peasants to take matters into their own hands and seize the land they now considered rightfully theirs, rather than wait for the slow pace of administrative procedures.[2] In this tumultuous time, the son of a prominent sheikh from the Maysan Governorate murdered the communist teacher Sahib Mulla Khassaf by the Kahla River. Khassaf, who served as the head of the Peasants' Association in al-Amara, had educated the fellahin about their newly granted rights and encouraged them to sell their harvests directly rather than handing them over to the sheikh. After the murder went unpunished, mass demonstrations erupted in al-Amarah. The fellahin went to the district governor holding up ropes, demanding that the sheikh’s son be handed over and calling for revenge, but to no avail. The son was released, and the charges were filed against an unknown person.[3]

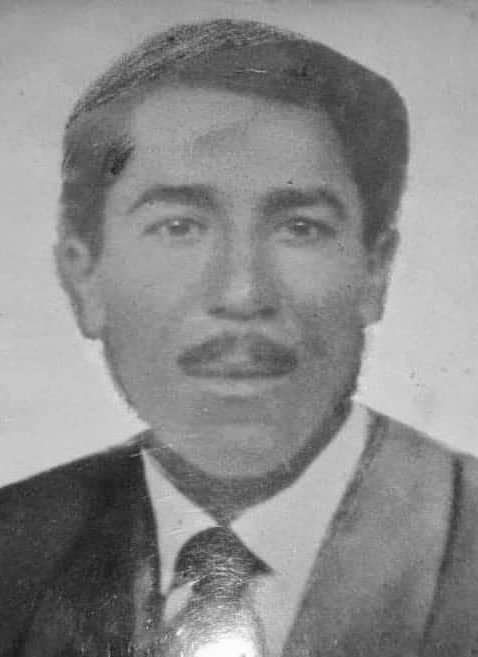

Sahib Mulla Khassaf. Image from مدونة سوسن

In the following poem, which was written in the same year, Muzaffar al-Nawwab draws upon these events, portraying Sahib Mulla Khassaf as a martyred peasant mourned by the village women. It is written from the perspective of the wife of the murdered man, who hears gunfire from a distance and instinctively knows that her husband has just been killed. She rushes outside to find the other women gathered around his bleeding body but implores them not to weep, so as not to mix the black of their kohl (black eye paint) with the red of his blood.

The poem’s original title is Mudayif Hel (The Cardamom Guesthouses), but it became widely known under the name Swaihib—a diminutive form of Sahib, reflecting a common practice of name-formation in southern Iraq, thus meaning “little Sahib”. It follows the traditional quintain form of regional dialect poetry with a triplet followed by a rhymed couplet (aaabb, cccbb, dddbb, ...) but departs from convention in both its imagery and narrative perspective.

The atmosphere evoked by a poem in the South Iraqi dialect is nearly impossible to capture in English. Shaped by the region’s rich musical and poetic traditions, the dialect carries a tone that is both melancholic and resolute. In order to preserve the oral dimension of his poetry, Muzaffar al-Nawwab recorded this and other poems in a studio, intending to release them on cassette alongside his diwan or broadcast them on the radio. This recording proved invaluable in helping me correct many of the errors found in the printed versions currently in circulation. In 1984, the poem was set to music by Sami Kamal.

The poem stands as a striking example of how literature can preserve historical events within the collective memory. Since, to my knowledge, the incident is not mentioned in the major historical works of the period, Swaihib serves as a valuable microhistorical source—one that has endured not in archives, but in the hearts and voices of the people. In Iraq, it continues to be memorized and recited to this day.

|

.بدأ الإقطاعيون بنهر الكحلاء، وابتدأت الردة

|

|

The feudal lords started at the Kahla River. And thus, the betrayal began.

|

|

ميلن لا تنگطن كحل فوگ الدم ميلن وردة الخزّامة تنگط سم جرح صويحب بعطابه ما يلتم لا تفرح ابدمنه لا يمگطاعي صويحب من يموت المنجل يداعي

|

Step aside! Don't let kohl mix with blood! Step aside! From the the nose rings, poison drops. No burned cloth can seal now Swaihib's wound. But gloat not, landlord, over our spilled blood— When Swaihib falls, the sickle of vengance calls!

|

|

|

حاه شوسع جرحك ما يسده الثار يصويحب وحگ الدم ودمك حار من بعدك مناجل غيظ ايحصدن نار شيل بيارغ الدم فوگ يلساعي صويحب من يموت المنجل يداعي

|

Oh, how deep your wound, no vengeance can heal, Swaihib, by your blood that still runs hot, I swear: After you, the sickles of wratch will reap blazing fire. Wave the banners of blood, you who carries the news: When Swaihib falls, the sickle of vengeance calls!

|

|

|

ميلن لا تغيظنه بچه صويحب وبجفنه النِدي نجم الكحل غايب لو يشرِگ اردود المسچ ونعاتب عتب النده بروح البردي يلناعي وملامع عيون انعجه للراعي

|

Step aside! Don't disturb him! When Swaihib cried a kohl-like star slipped from his weeping eyes. If only the musk would rise once more, we blamed [its leaving] as droplets chide the read [in the flute], O mournful singer, like sheep with eyes glinting at the sight of the shepherd.

|

|

|

لتفر عن نثايه العين شدنه ميلن وردة الخزّامة عالحنّه صويحب ما مش صويحب أبد منّه هذا إيشان ما ينذل يلگطاعي وبليل الخناجر منجله يداعي

|

Don't startle girls within your eyes but hold them back, hold back your nose rings from henna-painted hands! Swaihib... There's none who'll ever match his name, a mountain, landlord, that won't me touched by shame and when daggers are drawn at night, his sickle of vengeance cries.

|

|

|

ودّن على المكاحل يا مضايف هيل غطنّه بكحل دخله ومحبة ليل حبك سچة يصويحب هجرني الريل لتشيلك مذلة الريل يلگطاعي من ريل الرميثة المنجل يداعي

|

Take him to kohl bottles, you guesthouses of cardamom! Shroud him in wedding-night kohl and night's love! Your love is a rail, Swaihib, but the train has left me. Landowner, don't be fooled by the train's defeat! From Rumaytha's train, the sickle of vengeance is calling.

|

|

|

هاي آنه الأحضنك لا تلم روحك أضمك بالگصايب عين لتلوحك يصويحب أفيّ الفيه لجروحك يتلاگن عيون الذيب بشراعي وحاه اشكبر ضحچات الاگطاعي

|

I will cradle you and gather your soul with my hands. I'll hide you in my braids, shield you from every gaze. Swaihib, I shadow the shadow for your wound. But within my shielding sail, the eyes of wolves gather. Ah, Swaihib, how loud the landowner's spiteful laughter.

|

|

|

صويحب على العگل صندوگ عرس اچبير حزمة من الحصاد ايلفها طيب چثير وين اللي يگلي فلان وين ايصير أوصله وأدگ شراعه بشراعي صويحب من يموت المنجل يداعي

|

Swaihib is a big wedding chest on men's proud heads, a cluster of harvests where all the perfumes whirl. Who leads me to the traitor, who shows me where to go? I'll find him, and against his sail I let my own sail blow. When Swaihib falls, the sickle of vengeance calls!

|

|

|

صدور الغيظ اينفثن نار على المشرگ وچفوف الفلح لمة شمس تحرگ ها يالحكم هاي شرايع اتمزلگ والخنزير يزلگ بيها يلراعي وصويحب يموت ومنجله يداعي

|

Wrath-filled breasts blow fire toward the east, and in peasants' palms burns the blazing sun. O judge, your rulings slide on slippery ground, O herdsman, over them, even pigs are tripping Swaihib falls, and the sickle of vengeance calls!

|

|

|

حاه يصويحب الدگات ايفتحن دم وبشيمة عطش تنده اليشامغ سم يلنجمك حمر عدّه العگل تلتم طيب الذات خاوه الذيب والراعي وتوالم عرس واويه واگطاعي

|

O Suwaihib, they have beaten their chests until they bled, and from the scarves on the heads of thristy men, poison drips. O you whose star burns red, where the agals gather, the kind-hearted, through him, shepherd and wolf are allied, and the jackal fits well for the landlord's bride.

|

|

|

طشّن طيب وخزّامات ورز عنبر وبحسن الگصايب حنّن المعبر ما هي جروح يصويحب نگش خنجر حسّك حسّك اتنبّر يهلناعي صويحب من يموت المنجل يداعي

|

Spread anbar rice with lavender and scent! With the grace of braids, adorn the bridge! These are no wounds, Swaihib, but the engravings of a dagger. Raise your voice louder, singer of death: When Swaihib falls, the sickle of vengeance calls!

|

|

|

صويحب هاي حبتك لا تطول الموت من تسمع شچية الفلح رد الصوت هاي الدنيه عيب يضيج بيها الفوت البد البد ابدمك يلگطاعي كل بيدر وراه المنجل يداعي |

Swaihib, this kiss is for you, don't stay dead too long! When you hear the peasants' grief, answer strong, let death not weigh too heavy on this world! Sink in your own blood, landowner, beware behind each harvest heap, a sickle of vengeance awaits you there. |

II

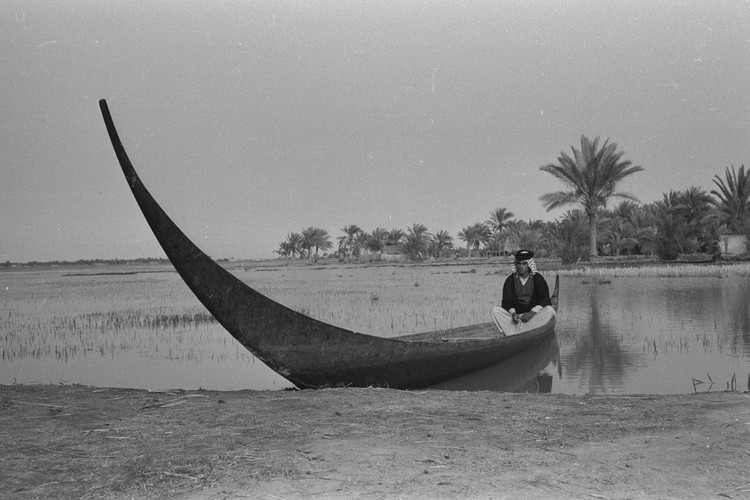

Iraqi man in a meshhouf. Image by Pitt Rivers Museum

Fifty-eight years ago, in 1967, the Iraqi Communist Party experienced a major split. At the heart of the conflict was the question of how to deal with the new regime that had come to power four years earlier through a military coup. While one faction advocated for cooperation with the government of Abdul Rahman Arif, another wing of the party vehemently rejected any form of collaboration and instead called for armed resistance. That same year, the Iraqi poet Muzaffar al-Nawwab (1934–2022) escaped from the prison of Hilla through a tunnel he and fellow inmates had dug by hand. Shortly thereafter, he joined the guerrilla fighters in the marshes of southern Iraq.

In the region around Al-Hay, he met the peasant Jabir al-Baylasan, who, like several villagers in the area, had taken up arms in support of the communist cause. Twenty years after Muzaffar al-Nawwab’s forced exile from Iraq, he dedicated the following poem to Jabir’s memory.

As with much of al-Nawwab’s oeuvre, this poem exists in multiple versions, making the text presented here merely a fleeting snapshot in its life. Owing to al-Nawwab’s habit of continual re-writing and his belief in poetry as a primarily performative art, the majority of his work was never committed to print. This translation is therefore based on an audio recording of a live reading held in Copenhagen in 1992.

Al-Baylasan, the peasant’s family name, is the Arabic word for elder tree.

Introduction:

جابر فلاح عراقي كان معنا أيام الكفاح المسلح في جنوب العراق. كان مصاب بالسل في آخر درجات السل، درجة ثالثة، في المنطقة التي كنا فيها، كان ٢٥ ألف إصابة بالسل. وكان يلح علينا أن ابعثوني بأي عملية، ابعثوني إلى فلسطين، إلى بغداد، إلى أي مكان قبل ما أموت بالسل. بعدين مات جابر وشيعناه.

Jabir was an Iraqi peasant who fought alongside us in the armed struggle in the south of Iraq. He had terminal tuberculosis in a region where 25,000 people were infected with the disease. He urged us: “Send me on a mission—any mission—to Palestine, to Baghdad, anywhere, before I die of tuberculosis.” Then Jabir died, and we buried him.

|

آه يا جابر البيلسان |

Ah, Jabir al-Baylasan! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

جابر كان بعد القناطر |

Beyond the stone bridges, |

|

|

حقلا من البيلسانِ العراقي |

Jabir was a field of Iraqi elderflower, |

|

|

نلوي إليه زمام الطريق |

to whom we offered the reins of our road. |

|

|

كان في عز حمّى التدرّن والقيظ |

In the fevered grip of tuberculosis and heat, |

|

|

يجمعنا مثلما لبّة الخس |

he gathered us like a lettuce heart |

|

|

في ظله الدسم |

beneath his nourishing shade. |

|

|

كاللّعب بالحلمات |

As if caressing female nipples, |

|

|

يحمص قهوته والأماني |

he roasted coffee and hope, |

|

|

ويقرأ سيرة حرب العصابات |

and in the presence of all, |

|

|

للحاضرين |

he recited the valor of guerrilla wars, |

|

|

ولم يبق مِن رئتيه |

but all that was left of his lungs |

|

|

سوى سعلة وهلال رقيق |

was a cough and a fine crescent moon. |

|

|

ويرشف ما قد تبقّى من الهال |

He licked the remnants of cardamom |

|

|

في شاربيه |

from his moustache, |

|

|

وتصعد في اللّهب الذهبي |

while in golden embers |

|

|

ملامحه والسّعال وأحلامه |

his features, his cough, and his dreams ascended. |

|

|

وبرغم الهواء الذي يتدرّن في الليل |

Despite the tuberculosis laden air, |

|

|

كنا نرصّ بخيمته |

we would tie at night |

|

|

حزن أيامنا والسروج وحصّتنا من غد وانتظارا |

the sorrow of our days, the saddles, tomorrow’s lesson, |

|

|

عتيق |

and an age-old waiting within his tent. |

|

|

شاحب مثلما ينقضي موسم |

Pale as the waning season |

|

|

البيلسانِ العراقي جابر |

of Iraqi elderflower was Jabir. |

|

|

لم يلتزم بسوى القمح |

He pledged himself only to the wheat, |

|

|

رغم انتقاد النعاجِ التي هرمت |

despite the scorn of sheep grown old |

|

|

في النضال السياسي |

in the trials of political struggle. |

|

|

ثم ترحّل عنّا |

Then he left us. |

|

|

حملنا محفّة أوجاعه |

As the river of the Milky Way is carried to its grave, |

|

|

في ضباب الخريف |

so we carried the bier of his anguish |

|

|

كأنّا نشيّع نهر المجرّة |

through the autumn mist. |

|

|

ما كان غير التدرّن فوق المحفّة |

Upon the bier was only tuberculosis, |

|

|

ما كان غير العظام |

only bones, |

|

|

التي مثل أعواد كدس من البيلسان |

stacked like the sticks of an elder bush. |

|

|

وكان المناضل جابر ينتشر الآن |

Jabir, the fighter, now unfurled |

|

|

مثل ضباب السواقي |

like fog over waterways. |

|

|

وفي حفرة |

In a pit, |

|

|

من سكوت الصباح |

filled with morning silence, |

|

|

دفنّا تقيّحه باليمين الشيوعي |

we buried his festering wounds with the communist vow, |

|

|

ثم تلونا سكون الصباحِ على قبره |

then read aloud above his grave the silence of dawn. |

|

|

زهرتان من الكحل من صلب قهوته |

Two blossoms of kohl, drawn from the depths of his coffee, |

|

|

حدّقتا بالرجال وأجهشتا بالرحيق |

lifted their gaze to the men and wept nectar-tears. |

|

|

إذا جاء جابر يوم الحساب |

When Jabir appears on Judgment Day, |

|

|

بليغ التدرّن والصمت |

eloquent in tuberculosis and silence— |

|

|

تلكم أهمّ لغات المحبين يا سيدي |

for these, sir, are the chief tongues of lovers— |

|

|

ستكون بطاقته للدخول على الله |

his ticket to God |

|

|

نفس بطاقته في الكفاحِ المسلّحِ |

shall be the same he bore in armed struggle. |

|

|

خذ بالمتيّم بالأرض |

Take away the one who loved his land in drunken devotion, |

|

|

جابرُ يا ربّ للرافدين |

Jabir, to the Two Rivers, O Lord! |

|

|

فإن العراق أحبّ الجنان إلينا |

For Iraq is our dearest paradise, |

|

|

وإن أخطأ البعض منّا الطريق |

and though some of us strayed from the path, |

|

|

ستلقاه لم يتغير |

It never changed, |

|

|

كما يعبق البيلسان ضحى |

like elderflower fragrant at dawn, |

|

|

وكما يأرق البيلسان مساء |

and watchful at dusk, |

|

|

عميقا عميق |

so deep. |

|

|

ما زال يعبر فوق القناطر كالأمس |

Still, he crosses the stone bridges as yesterday, |

|

|

والمشمشات الصغيرات تحمل بين يديه القناديل |

and the little apricots in front of him still carry lanterns. |

|

|

يأخذ حافلة الليل |

He boards the night bus |

|

|

تأخذه للبلاد التي لا يعود المسافر منها |

that leads him to the land from which no traveler returns. |

|

|

سيمطر حزن العراق |

The sorrow of Iraq |

|

|

على جابر البيلسان |

will rain upon Jabir al-Baylasan, |

|

|

وينمو التدرّن فطر على القبر |

and on his grave, tuberculosis will sprout like a mushroom, |

|

|

ما هدر الرعد |

so long as the thunder roars |

|

|

واخضلّ قلب العراق السحيق |

and the heart of ancient Iraq stays moist. |

|

|

آه لو ثبت الآخرون ثباتك |

Ah, if only the others stood as firm as you, |

|

|

يا ملك السل والصبر |

King of Tuberculosis and Patience, |

|

|

ما ضاع منّا العراق |

we would not have lost Iraq, |

|

|

ولا الروح ظلَّت تحشرج عشرين عاما |

and the soul would not have wheezed for twenty years |

|

|

بلا مهجع من حنان ولا نظرة من صديق |

without a bed of tenderness, without the glance of a friend. |

|

|

آه يا جابر البيلسان. |

Ah, Jabir al-Baylasan! |

[1] At the time of the reform, 56% of privately owned land was held by approximately 2,800 sheikhs. See Hanna Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq (Princeton and New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978), p. 837.

[2] The chaotic course of the first years following the reform is described in Edith and E. F. Penrose, Iraq: International Relations and National Development (London et al: Ernest Benn Limited, 1978), p. 240-248.

[3] A detailed description of the events can be found here: سعدي جبار مكلف: صويحب مظفر النواب ومنجله المندائي, accessed [01.07.2025], from https://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=567338, and

سلام عبود: مظفّر النوّاب: محيي الموؤودات الشعريّة, accessed [01.07.2025], from https://www.al-akhbar.com/Literature_Arts/337309/ساحر-الكلمة-النابضة-وشيطان-المفردة-الحية.