[28 September 2020 marks fifty years since the death of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. His “July Revolution” of 1952 reshaped the politics, economy, and cultural life of modern Egypt and profoundly influenced those of the Arab world, as well as the fortunes of European empire and the course of the Afro-Asian and nonaligned movements of the twentieth century. Abdel Nasser's legacies continue to be invoked and contested in contemporary Arab politics, while several Nasserist parties have endeavored to repurpose his political tradition. On this significant anniversary, Jadaliyya's Egypt page publishes three articles in succession to critically engage with these legacies. Its editors invite fellow scholars and students of the Nasser era to send in further contributions that do the same. Read the first article and second article in the series here.]

"It was the abortive Suez adventure of 1956… that united all Africa, and Africa with Asia and the Arab world, to give a great spurt forward to national independence… Africa was never the same after Suez…"

- Kenyan independence activist and later vice president Oginga Odinga, Not Yet Uhuru, London: Heinemann, 1967, 175

"When we saw that Nasser could nationalize the Suez Canal, resist the French and the British, and win, we said to ourselves, this is someone who can really help [the UPC]."

- Marthe Moumié, Union of the Peoples of Cameroon activist, Victime du Colonialisme: Mon Mari Félix Moumié, Paris: Duboiris, 2006, 100

These words come from the memoirs of leading figures in two major African national liberation movements. Both of them formed close connections with Egypt’s leadership in the mid-1950s, and were hosted in its capital. Their engagement with the Suez nationalization forms part of a largely unknown story, despite the extensive historiography on the period. This is the story of the production of Cairo as an anti-imperialist hub under Gamal Abdel Nasser, through the construction of an infrastructure of solidarity that connected progressives in Asia and Africa, Europe, and eventually South America.[1] It is one fraught with obstacles, compromises, and competition, but equally reflects a politics of hope and liberation that is key to the resonance of the Nasserist experience to this day.

Yet Egypt’s Afro-Asian engagements, like its role within the non-aligned movement, and its links with the Tricontinental, have been overlooked in Middle East studies. Indeed, in the eyes of many, the Nasser era is a closed subject. Though there are notable exceptions, it is still introduced relentlessly to students of the Middle East within the frames of an authoritarian regime, failed developmental state, and nationalist mirage. Yet remaining within these frames does not help us understand why pan-Arabist identifications resurged during the 2011 uprisings, why Abdel Nasser’s image has been raised at so many protests in Egypt and beyond since the 1970s, nor why—as Laura Bier argues in her contribution—Nasserist ideological frameworks persist in Egypt today.

Marking fifty years since Abdel Nasser’s passing is an opportunity to propose new lines of inquiry. These might engage critically with the politics of solidarity in his project beyond the Arab scale, and the politics of identity which these relations engendered. How were diverse political friendships formed beyond Egypt, what were their challenges and limits? How did the national and transnational coexist in state agendas and citizens’ political imaginaries, and how did this evolve? They might also re-examine the era’s legacies and explore illuminating comparative experiences. This contribution takes up some of these questions by revisiting the Suez nationalization through an Afro-Asian telling. I argue that these events offer a compelling case study for theorizations of solidarity as generative of new relations across transnational boundaries, and as transformative of current political identities. It also reveals the extent to which non-state actors were involved in the anti-imperialist state project, reimagining their identities beyond the Egyptian/Arab binary. Grasping these popular and normative dimensions illuminates the wider legacy of the Nasser experience.

Before Suez: Seeking New Friends, Building a Base

Suez is often presented as the inception, or else the moment of fabrication, of Abdel Nasser’s Arab nationalist stance in Egypt. Yet the historical record reveals that pan-Arab engagement had got underway earlier, soon after Abdel Nasser’s Free Officers Movement came to power in July 1952.[2] Moreover, Arab nationalism comes into view as only one—if certainly the most immediate and affective—of several frames for Egypt’s anti-imperialist politics at the time, which extended to the African and Afro-Asian too. Indeed part of the reason Suez could resonate as widely as it did was that Egypt had established the Sawt al-‘Arab ("Voice of the Arabs") Cairo Radio station in 1953, and several African-language radio programs the following year, whose political broadcasts were widely popular.

The mobilizing role of Cairo Radio was part of a nascent Arab and African policy of solidarity and patronage, which reflected Abdel Nasser’s conviction that national development and national liberation were intertwined, and that neither could be achieved amidst the colonization of Egypt’s wider Arab and African space. In an effort to break its dependency on the West for material assistance, Egypt sought new friends and spheres of influence. Bolstered by ties with decolonizing African and Asian states, Egypt could more effectively challenge the hierarchies of a colonially constituted international system, and play off the superpowers of its Cold War bipolar structure for more resources.

This reasoning underpinned the Egyptian intelligence’s founding of a new Bureau of Arab Affairs, its launch of Sawt al-‘Arab and support for the Algerian National Liberation Front in 1953, and Abdel Nasser’s efforts to strengthen Arab collective security arrangements against the pro-Western Baghdad Pact established in 1955. It also informed Egypt’s Afro-Asian engagements, which had originally begun during the Anglo-Egyptian talks on British withdrawal and the fate of Sudan in the early fifties. To put pressure on Britain, the Egyptian leadership endorsed India’s declarations of its Cold War neutrality in 1953, and fostered ties with Egypt’s Nile Valley neighbors. Cairo Radio began programming in Amharic, Sudanese dialects, and Swahili in July 1954. Its broadcasts affirmed Egyptian support for African issues such as the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya, and spread the word of Egypt’s own affairs. Abdel Nasser then attended the Asian-African Conference at Bandung in 1955, completing an Asian tour that featured stops in Delhi and Rangoon, and a flurry of network building throughout. At Bandung, Abdel Nasser affirmed Egypt’s solidarity with all colonized nations, and its rejection of Western security pacts. He also negotiated the Czech arms deal, breaking the Western monopoly on arms sales in the region.

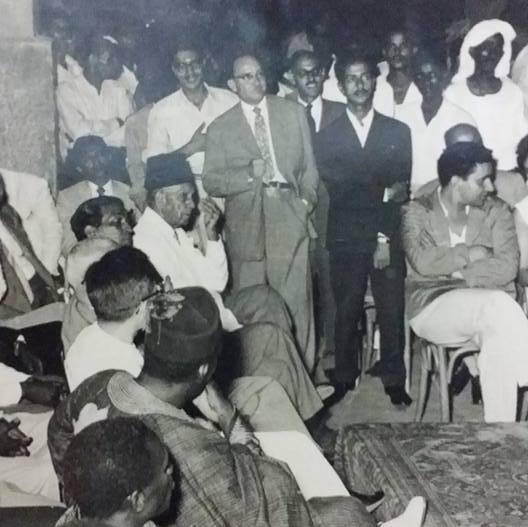

In late 1955, Free Officer Muhammad Fayiq oversaw the establishment of the African Association in Zamalek, whose official function was pastoral care for the thousands of Africans on Egyptian university scholarships. Under the stewardship of former diplomat Abd Al-Aziz Ishaq and young Arts graduate Helmi Sharawy, it became a space for Cairo’s African community to organize politically, as the government began to offer individual liberation movements offices and diplomatic support.[3] As the Soviets and Chinese also competed for their favor, Egypt offered them a non-communist, statist national liberation model which commanded significant influence. The Association also became a political-cultural hub for Egyptians engaged with African affairs. Sharawy was subsequently appointed Coordinator of African Liberation Movements in the presidency’s Bureau for African Affairs. As he discusses in his memoir, however, the Association’s membership drew on intellectual-cultural circles, and most shunned political outfits such as the official mass party. This reflected the resonance of the state’s ideological mission, and the energies many Egyptians were prepared to devote to it, without becoming part of the new regime.

Helmi Sharawy (standing center right) with Abd al-Aziz Ishaq at the African Association during the visit of a Ghanaian delegation to Cairo, c. 1958 (Source: Helmi Sharawy’s personal collection).

The Suez Nationalization and War: Cascades of Solidarity, Patronage Politics

These policies accelerated Anglo-American plans to outmaneuver Abdel Nasser, and when they withdrew their funding for the Aswan High Dam in July 1956, he announced the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company. Egypt received swift support from Soviet Russia, China, and India, but also from labor and liberation movements across Asia and Africa. It was arguably these cascades of solidarity that declared Suez a global event, and illustrate the generative nature of Egypt’s solidarity praxis until then. Cairo’s endorsement of liberation causes now saw reciprocation and the forging of new connections on a mass scale, in expressions of Afro-Asian liberation movements’ own aspirations as much as their support for Egypt’s action. Certainly, Abdel Nasser’s speech on Suez had been explicit about its wider reverberations, citing the Bandung principles, and their adoption at his recent Brioni meeting with the nonaligned heads of state, Yugoslav premier Josip Broz Tito and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He repeatedly slammed Britain and France’s colonization of Africa and Asia: “There is no shame in being poor and borrowing to build one’s country, what is shameful is the sapping of the blood of nations, the rights of nations…” However the response in popular transnational solidarity provided Abdel Nasser with unexpected reserves of soft power, and strengthened Egyptian resistance to the pressures of the Western powers.

Indeed, when Abdel Nasser boycotted the first London Conference on Suez, trade unions across the Arab world called a general strike in support of Egypt’s position. The story of solidarity actions across Africa and Asia is underexplored, and deserves further research. It peaked in October 1956, when Israel, Britain, and France mounted their joint attack. A case in point is the South African anti-apartheid movements, who vocally supported Egypt. The African National Congress declared its support in its journal, Liberation, and signed a joint statement of solidarity alongside other progressive associations and unions, published in the communist newspaper New Age. The issue’s editorial described their multiple mutual entanglements with Egypt:

As an African country, we are closely involved in this invasion of Africa. As members of the liberation movement, we are closely involved in this attack on a liberation movement. As opponents of national oppression and colonialism, we are involved in this oppressive and imperialist war…

The ANC further declared that the tripartite attack had "raised against themselves a storm of mass solidarity, indignation, and determination that can only hasten the doom of imperialism and colonialism throughout the world."

Years later in 1961, Nelson Mandela visited Egypt for the first time, and the ANC later established an office in Cairo:

Egypt was an important model for us, for we could witness at firsthand the programme of socialist economic reforms being launched by President Nasser… that we in the ANC someday hoped to enact. At that time, however, it was more important to us that Egypt was the only African state with an army, navy, and air force that could in any way compare with those of South Africa.[4]

Indeed, the African Association in Cairo saw a sudden swell of visitors following the Suez nationalization, as several movements took the initiative to make contact. This occasioned new and deeper connections, further illuminating the generative nature of the Association’s early solidarity practices, and the flow of solidarity in both directions at different times. The Association’s functions now encompassed the facilitation of communications between different Cairo-based African liberation movement leaders, and contact with their bases at home. This included making introductions at Cairo Radio, and featuring their writings in the Association’s current affairs magazine Nahdat Afriqya ("Africa Rising"), founded in October 1957. Liberation movements could use these channels to undermine the borders imposed by colonial and apartheid states, to expand their networks, and to exchange information and share skills in a safe space. One of the first delegations arrived in July 1957 and was headed by the Cameroonian liberation leader, Felix Moumié. His widow Marthe Moumié later commented: "All the parties represented in Cairo, with the support of the Egyptian government, had a spirit of manifest solidarity. The Algerians, Ugandans, South Africans, and Cameroonians consulted one another about strategies to adopt in their struggle against colonialism. The UPC office in… Zamalek, Cairo, occupied an important place."[5]

At the same time, the limitations of resources constrained these movements’ repertoires, leading some to establish bases in competing capitals such as Accra and Algiers, or even in colonial metropoles. For example, Joshua Nkomo, president of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) (and later Vice President of Zimbabwe), was hosted in Cairo and forged a strong friendship with Sharawy, but eventually sought to organize from London.[6] There were also differences of political priority and analysis: Sharawy recalls struggling to convince his friend Nkomo of the similarities between settler-colonial rule in Rhodesia and Palestine, Algeria, Kenya, and South Africa.[7] Meanwhile, Israel was presenting itself in Africa as a fellow newly independent state. Thus, the posture of solidarity by Egypt did not spell compliance with its preferences, and an important dynamic in these relations was the ability of liberation movements to repurpose Egypt’s patronage, just as Abdel Nasser himself did with Egypt’s own Soviet and US donors of aid.

After Suez: Forging Identities Beyond State and Nation

Egypt’s enhanced stature after Suez had widened its solidarity connections, and these were transformative of political imaginaries and communities in turn. Significantly, Suez had attracted the attention of the peace movements that had in 1955 organised the popular Asian Solidarity Conference (ASC) in Delhi: in December 1956, they invited Abdel Nasser to host the first Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Conference. Held in December 1957, the Cairo Conference hosted activists, unionists, writers, and artists from forty-six countries yet to achieve independence. The Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Organization was then founded in Cairo in 1958. Suez had therefore merged a trajectory of grassroots solidarity with state policy, connecting Cairo with other Afro-Asian locales, and enabling the largest ever meeting of anticolonial movements until that point. As its ASC precedent had been dubbed before it, Cairo was announced as the "People’s Bandung."

These developments announced a phase in which the Afro-Asian scale became a salient dimension of nationalist Egyptians’ political imaginaries. On the one hand, they sought to shape Afro-Asian agendas, particularly by tabling issues thus far considered exclusively "Arab," such as the liberation of Algeria and Palestine. At the Cairo Conference, for example, the Egyptian delegation moved a resolution on Algeria which described the French as engaged in a war of extermination, and another on Palestine which supported Palestinians’ right of return.[8] They secured both with the aid of the numerous movements now being hosted in Cairo. On the other hand, they made an effort to embrace the issues of others, from racist discrimination and apartheid in southern Africa to the spread of nuclear weapons in the Cold War to the challenges of economic development in the third world—all of which were discussed by leftist Free Officer Khalid Muhyi al-Din in his speech to the Cairo Conference.[9] The idea of a shared project, rather than simply a common enemy, began to characterize this solidarity practice.

The extraordinary engagement of Arab, African, and Asian publics with Egypt’s cause had also attracted the Egyptian public’s attention to the daily struggles for liberation in different neighboring countries. As the state media amplified this interest, ordinary Egyptians began to locate themselves within overlapping networks of anticolonial resistance. During Egypt’s intervention in Congo in 1960-61, for example, workers and students participated in demonstrations at the Belgian Embassy, and the press reported animatedly on the smuggling of Patrice Lumumba’s children to safety in Cairo. This was Lumumba’s direct request to Abdel Nasser, just days before his assassination. African Association Chair Abd al-Aziz Ishaq personally accompanied the children out of Kinshasa, and Sharawy was tasked with arranging their accommodation and education in Cairo.[10]

There is no doubt that in a country of thirty million, where inequality made class identity particularly salient, and where political culture was long shaped by narratives of Egypt’s distinct national identity, these Afro-Asian, internationalist affiliations did not make inroads as profound as their promoters hoped. They were often undermined by wider societal ignorance of their cultures and languages, and by racist attitudes, fostered in turn by tropes of civilizational superiority and legacies of slavery. Despite the government’s efforts to disseminate affordable literature on African and Asian affairs, and to overhaul school and university curricula, shifts in popular political culture were slow. More influential were arguably the media campaigns on Egypt’s Afro-Asian connections, which featured notable Marxist, liberal and nationalist public intellectuals, poets, and artists. The prominence of these voices helped construct new, popular meanings and connotations of liberation and dignity.

Following a neutralist states meeting in Yugoslavia, September 1960: Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of India, President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, President Gamal Abdel Nasser of United Arab Republic (Egypt), President Sukarno of Indonesia, and President Tito of Yugoslavia.

Legacies and Challenges

What does it mean to revisit such moments today? The question of Abdel Nasser’s legacies is hotly contested, and remains open, as shown by the myriad political usages of his name and image since Egypt’s 2011 revolution. It is noteworthy, however, that these legacies take in diverse elements of the Nasser project, beyond its pan-Arabism or welfare state. This was visible for example in the two "popular diplomacy" delegations of May 2011, in which about forty public figures went to Uganda and Ethiopia, and mobilized Nasser’s memory explicitly to redress the neglect of Egyptian-African relations under Mubarak. Abdel Nasser’s son Abdel Hakim was a prominent delegation member and received a warm welcome. A decade since, the conflict over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam has again tapped the culture of nostalgia for Nasserism, this time among both supporters and opponents of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s handling of negotiations, all of whom invoke the golden age of Egypt’s African engagement.

The Nasserism of these debates is a straightforwardly Afro-Asian phenomenon. This feature merits a revisiting of the politics of liberation struggles with which Egypt engaged under Abdel Nasser. In 1958, just three years after the Bandung Conference, leftist Egyptian historian Muhammad Anis described it vividly as "the moment of Arab nationalism’s exit from isolation," prompting its "fusion with Afro-Asianism" and "progressive humanism."[11] The African Association was arguably one of the most concrete manifestations of this new orientation. It is significant for the number of volunteers who powered its first years of activity, and the twenty-four movements it hosted by the mid-1960s, transforming Cairo into a major hub within the transnational solidarity networks of the day.

As developments that decade show, however, behind the romance of solidarity was a complex story of Egyptian interventions in Afro-Asian affairs, balancing the needs of friends with the pressures of rivals, and with priorities at home. Following the Congo coup, for example, Cairo joined other African leaderships in the progressive Casablanca bloc, challenging the conservatives of the Monrovia group, in an opposition that mirrors the much better known "Arab Cold War." However, in 1963, the two sides compromised, and Egypt helped co-found the Organization of African Unity. By 1964, Cairo was to play host to three world summits in one year: the Arab, African, and Nonaligned Conferences, reflecting its dynamism in all three fields. Egypt continued to be a prominent African player, not least in confronting Israel’s charm offensives and advances in the continent, until Abdel Nasser’s death in 1970.

In making sense of these multiple threads, the challenges to us scholars are to avoid methodological nationalism, and to pursue scholarship that reflects its subject in complexity: this necessarily entails collaborations across language and area specialisms. Thus, new scholarship might attend to Abdel Nasser’s relations with Nkrumah, Tito, and Nehru, and Egypt’s shifting relations with Algeria and Cuba, as well as to each of these progressive historical projects comparatively, as much as past literature has attended to Egypt’s relations with the Arabs and Israel. In so doing, we would surely better understand Abdel Nasser’s particular anti-imperialist project—its precise reach, influences, and limits, and how its different theatres of action interacted. Similarly, scholars might ask about the non-Egyptians influenced by the Nasserist project, what their positionalities and links with Egyptians were as it unfolded, and what their legacies have been in turn, helping to decenter the great man approach to history. In so doing, we would surely better understand why Mandela could speak of an "Egyptian model" in 1961, why new generations invoked this in Egypt in 2011, and why it seems certain that many will still be remembering Abdel Nasser’s project on anniversaries to come.

I would like to thank Amr Adly, Michael Farquhar, and Hilary Sapire for their helpful suggestions on an earlier draft.

[1] I discuss this in greater depth in Reem Abou El-Fadl, "Building Egypt’s Afro-Asian Hub: Infrastructures of Solidarity and the 1957 Cairo Conference," Journal of World History, (30)1-2, 2019, 157-192.

[2] I discuss this in greater depth in Chapter Five of Reem Abou El-Fadl, Foreign Policy as Nation Making: Turkey and Egypt in the Cold War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

[3] See Helmi Sharawy, Sira Misriyya Ifriqiyya: Mudhakkirat Helmi Sharawi (‘An Egyptian African Story: The Memoirs of Helmi Sharawy’), Cairo: Dar al-Ain, 2019.

[4] Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, London: Little Brown and Company, 1994, 285-6.

[5] Marthe Moumié, Victime du Colonialisme: Mon Mari Félix Moumié, Paris: Duboiris, 2006, 102-3.

[6] Joshua Nkomo, The Story of My Life, London: Methuen, 1981, 81.

[7] Sharawy, 102-105.

[8] Resolutions, The First Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Conference, Cairo: AAPSO, 1958, 39, 42.

[9] Khalid Muhyi Al-Din, “‘Imperialism and Upholding the Peoples’ Rights for Independence and Sovereignty’: Report by Khaled Mohieddin, Egypt”, First Conference, 81-6.

[10] Interview with Sharawy, Cairo, February 2019.

[11] Muhammad Anis, Al-Mu’tamar Al-Asyawi Al-Ifriqi [“The Asian-African Conference”], Ikhtarna Lak 44, Cairo, 1958, 160.