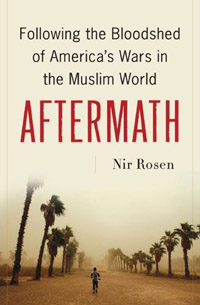

In my new book “Aftermath: Following the Bloodshed of America’s Wars in the Muslim World,” I look at sectarianism, civil war, occupation, resistance, terrorism and counterinsurgency from Iraq to Lebanon to Afghanistan. While half of the book looks at how the civil war in Iraq began and how it came to an end, other chapters look at the Taliban, the American military in Afghanistan and the Afghan police. The two chapters I am proudest of however deal with Lebanon, where I lived with my wife and son during the period I reported from there. I found that while the country was oversaturated with journalists (both local and foreign) and during times of crisis even more journalists parachuted in, most of Lebanon was still ignored. In particular the many villages in the Beqaa and Akkar have been neglected. I also found that most Lebanese knew very little about their country and few visited areas dominated by other sects. Hizballah receives attention because the U.S. media is so focused on Israel’s security, but I think many people would be surprised to learn about he extent of poverty and extremism among Sunnis in Lebanon. While Shiites have Hizballah to care for them, poor Sunnis are neglected, even though there are billionaire Sunni political leaders. The anger of poor Sunnis exploded in 2006 during the Danish cartoon riots. Because Lebanese Christians and European embassies were targeted this event made it into the news. But another incident of mob violence in 2008 is unknown even to many Lebanese. This account is an excerpt from one of my chapters on Lebanon:

[Excerpt from Aftermath (Nation Books, 2010)]

On the night of May 9 the mufti of Akkar, Osama Rifai, went on television and radio and called indirectly for the Syrian Social Nationalist Party to be attacked, as revenge against the SSNP activists who had burned down the Future TV office in Beirut. Attacking Hizballah’s weak ally in the north was a safe way to send Hizballah a message. “We’ll teach them a lesson,” he said. SSNP leaders and their allies believe that the Future Movement leadership, including Saad al–Hariri, gave an order for a response. Khaled Dhaher, a former member of Parliament and leading Islamist politician allied with the Future Movement, and Musbah al-Ahdab, an independent Tripolitan member of Parliament, helped to organize the response in the north. The decision was made to send a warning to the March 8 coalition in Halba. The SSNP had a weak presence in the north, and Halba was a small, majority-Sunni town whose people supported the Future Movement. The two parties had clashed three years earlier. On the night of May 9 armed supporters of the Future Movement took positions around Halba.

Halba is the capital of Lebanon’s northern region of Akkar. Many of the towns sitting on the mountainous region afford views looking down all the way to the Mediterranean Sea. Green fields surrounded the town, with houses scattered on the green hills above it. Like most of Lebanon outside Beirut, it is a lawless region, at least in the sense that the state’s presence is not strongly felt or seen. Shortly after 9 a.m. on the morning of May 10, young men set tires on fire and parked trucks to block the roads leading into Halba. Bright red flames rose from the tires and black smoke billowed up, concealing the low apartment buildings. The wind carried the stinging rubbery stench. Members of the Internal Security Forces, in their gray uniforms with red berets, strolled around next to the crowds of young men who stood around the burning tires. Others in the army’s green uniforms took a look as well. They were not armed. More and more young men gathered, many carrying clubs and metal bars. Some zipped back and forth on scooters. They disappeared into the smoke. The rain that started to fall did nothing to slow the activities or the flames. Some dragged sandbags to fortify their roadblocks. Tractors came with tires piled on them and young men sitting on top. In Lebanon there always seem to be tires available to burn at roadblocks. Cars approaching turned around to look for a different route. At first traffic continued as normal—these armed acts of civil disobedience are normal in Lebanon, and the Sunni leaders in the north used the loudspeakers on local mosques to call people together, and thousands of men gathered in the center of town for a demonstration. By now the sun was out again, shining on the sky-blue flags of the Future Movement as well as the green-and-black flags with Islamic slogans that men waved. Others carried posters of Rafiq and Saad al-Hariri. Many men clapped; others just watched. An Arab nationalist song from the 1960s blared from loudspeakers, sending the message that God would defeat the aggressors. Perhaps the organizers were trying to claim the mantle of Arab nationalism and deny it to their opponents. A speaker proclaimed that theirs was not a project of militias; it was the project of Rafiq al-Hariri, the project of education. Hariri did not graduate gangs or militias, he said. On one poster a man had written that Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah, whom he called Ariel Sharon, was fully responsible and should take his thugs and tyrants out of Beirut. Another sign said, “Saad is a red line.”

Men shouted to God. Others chanted, “Oh, Nasrallah, you pimp! Take your dogs out of Beirut!” (which rhymes in Arabic). “Oh, Aoun, you pig! You should be executed with a chain!” “Tonight is a feast! Fuck Nasrallah!” “Nasrallah under the shoe!” “Who do you love? Saad!”

Suddenly in the distance shooting started. Some men ran away, while others ran toward it. One man in a loudspeaker shouted, “Fight! The order is yours!” Another man called for caution. “The Internal Security Forces should take the proper position so there won’t be any attack here, and we ask the army to control the situation,” he shouted. “The mufti is coming. Brothers, we need to control ourselves. We are delivering the wrong message to the others. We did not come to fight.”

Armed men stood on the top floors of apartment buildings, looking down from balconies. Others on the street with M-16s and AK-47s used buildings for cover. Exchanges of fire echoed through town. Men gathered in corners and peered over to see where the shots were coming from. Crowds remained in the center of town, and religious leaders from Akkar’s Sunni Endowment hurried to the scene to take part in the demonstration. Some were guarded by armed men in civilian clothes. Some members of the Internal Security Forces and Lebanese army also stood watching.

That morning fourteen members of the SSNP were manning the local party headquarters, which was in an apartment building off the main road, surrounded by trees. Founded in 1932 by Antoine Saadeh, the SSNP is an Arab nationalist party that calls for the establishment of a Greater Syria uniting all the countries of the Levant. It is one of the smaller parties in Lebanon, but it had allied itself with the powerful Hizballah and Amal-led March 8 bloc, and its militiamen were known for being more thuggish than most. It is not clear exactly what happened in the first moments of the battle, but one version sug- gests that around ten o’clock that morning hundreds of armed Future Movement members and supporters attacked the SSNP office with automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenades. The SSNP members had some light arms in their office, and when they returned fire, two of the attackers were killed. Another version, equally plausible, is that a mob armed with sticks and clubs began to attack the SSNP office, and it was then that two of the Future Movement supporters were killed by the SSNP men inside. Armed attacks against the fourteen men inside the office followed. Trucks brought more men from the area into town. Many of the vehicles belonged to Future Movement officials or allies such as Khaled Dhaher.

Sporadic gunfire soon turned into steady volleys and exchanges. After a few minutes the first RPG hit the building. Two hours later the fire was so intense that the SSNP men asked their leadership in Beirut to help them get out. The Beirut office tried to coordinate with the Lebanese army and Internal Security Forces, attempting to negotiate the peaceful surrender of the SSNP men to the army. The building had been set on fire, and by then the smoke was making it difficult for the men to stay inside.

Muhamad Mahmud Tahash was one of the SSNP men inside. A low- ranking member of the party, he had gone to the office that morning completely unaware of what the day had in store for him. “RPGs were coming down like rain,” he later told me. “There was heavy shooting, and no army outside.” He went out of the building, hoping to seek the army’s protection, and was shot in the shoulder. “It shattered my bone,” he said. “I started walking in between people to go out, then the rest of the men went out as I was walking. I was beaten by people with rifle butts and screwdrivers.” He would later receive fifty stitches on his head. “I fell on the ground and they dragged me away to the Future Movement office, where they beat me,” he said. The other men who followed Tahash out of the building were all unarmed. They had reached an agreement with the Lebanese army, and they assumed that the Future Movement supporters and militiamen were part of the agreement. The local Future Movement leader, Hussein al-Masri, who was present for all the day’s events, had indeed told the army he agreed. But when the SSNP men emerged, one was hit with three shots and killed; another pretended to be dead; the others were all captured. Among them were other low-ranking members, guards, administrators, and a member of the local management committee. The Lebanese army was not there, but hundreds of armed men were. The SSNP men were beaten with stones and sticks, stabbed, burned, and shot in their legs to prevent their escape. The mob’s attack was filmed by many of the participants.

The men were sprawled on the ground, swollen, bloody, and barely conscious. Hundreds of men continued to beat and taunt and shoot at them. “Mahmud, shoot him!” one man called out as somebody cursed a victim’s female relatives and shots were fired. “We are Islam!” someone else shouted.

“God will make us victorious!” “Shoot him! This is for Beirut! Fuck his mother! You think we are Jews that you’re shooting at us? Shoot the fucker! We are the rulers, you brother of a whore! Are you proud of yourself for shooting a Muslim?” “This guy shot Hariri’s picture! This guy, this guy!” the man was then beaten with a stick. “God won’t give you mercy! I’m going to shoot you like you shot my cousin! God is great!” One man in the crowd pleaded for the at- tackers to stop. “Enough, he’s dead, enough! Oh, Muslims!” Others continued to attack and shout. “You infidels! You Jews! By God, I’ll fuck your sister.” “Bring the flagstick,” somebody shouted. One of the victims was stabbed with a stick. “God is one! Pray for the Prophet!” The same lone voice continued to plead, “We are Muslims! In our religion this is forbidden! If they don’t know the religion we know the religion! Act like Muslims! Guys, act like the Prophet has told you guys! Guys, we are Islam, God will give us victory . . . please, please!” One young boy asked to be allowed to abuse the wounded men. “I don’t want to do anything, I don’t want to do anything,” he said. “I just want to break his arm.” “We have four men in here and we have one inside as well! Guys, burn them! Burn them now!” “By God, I’ll fuck your sister!” One of the wounded men moaned, “Oh, God! Oh, God!” One man pointed to one of the victims’ necks and said, “I’m going to shoot you here! You’re not going to die alone!” “Enough, Nabil, leave him!” Someone pleaded, while elsewhere the attack continued. “This is the first bastard that started shooting at us! And this one too, he shot at us directly, this one! Film me while I put my slipper in his mouth, film me!” “Make us proud, guys!” One young attacker with a Future Movement headband shouted to the men, “We want to fuck your sisters!” “Shoot the second one, come on!” “Fuck his mother!” “Guys, burn them!” “I’ll fuck your sister!”

Two adjacent buildings were also attacked. Hundreds of men surrounded them and shot from all sides. “God is great!” they shouted as they burst into apartments and ransacked them. Residents were terrified; there was nobody in charge. They broke into one family’s house and threatened a mother and her children, pointing their guns at them. “We will kill you,” they said. One of the boys was nine years old. As one group of attackers left the apartment another would charge in, and the terror would begin again. As the families from the apartments fled down the streets, they walked past bodies and pools of blood. One of the apartments belonged to a Christian Lebanese army officer and his family. Like their neighbors, they watched their furniture get destroyed, their clothes flung about, their apartment shot up. “When there is so much violence and hatred, it’s impossible to build a state,” the officer later told me. The eighty-year-old father of one of the Christian SSNP members was also in a nearby building. Despite being weak and sick, he too was detained for much of the day and threatened with death. The office of Arc en Ciel, an aid organization that helped the handicapped and was located above the SSNP headquarters, was looted and destroyed. A nearby gas station whose owner was affiliated with the SSNP was also torched.

Survivors of the attack on the SSNP office who made it to local hospitals were attacked by mobs that were waiting for them. Nasr Hammoudah was killed when a fire extinguisher was shoved into his mouth and emptied into him. Mohamad Hammoudah, Abed Khodr Abdel Rahman, and Ammar Moussa were also attacked on their way to the hospital and upon their arrival.

Khaled Dhaher was one of the leaders of the mob. Witnesses implicated him in ordering some of the executions and even of shooting the SSNP prisoners himself. Dhaher protected Muhamad Tahash from execution and interrogated him, asking him how many men were in the office and what kind of weapons they had. One of the men approached and shot Tahash in the belly. Dhaher’s bodyguard, who was Tahash’s childhood friend, helped spare his life. He prevented a man from executing Tahash, so instead the man kicked Tahash in the face and broke his teeth as Dhaher looked on. While in captivity, Tahash observed Dhaher giving detailed orders to the mob. Dhaher told his men to at- tack the local Syrian Baath Party office. They told him it had been closed for three years. “I don’t care,” Dhaher responded. “Break in and burn it.” Muhamad al-Masri, a local Future Movement leader, was also present. Dhaher’s bodyguard locked Tahash in a room and called the Internal Security Forces to pick him up. They drove him to the hospital in a white civilian Mercedes-Benz. Tahash saw the mob waiting to kill survivors of the massacre. “I was left in the Mercedes by myself,” he said. “Men came and tried to cut my arm off. They couldn’t, so they twisted it and broke it. Then they emptied a fire extinguisher in my mouth and all over me. While they were attacking us, they accused us of defending Hizballah and the Shiites.” Tahash’s wife learned of the attack in Halba from the news. She called her husband’s mobile phone, but a stranger answered. “Muhamad was burned to death,” he told her. “Fuck you and fuck Antoine Saadeh [founder of the SSNP].”

As the men lay dying on the dirt, their attackers and other gleeful onlookers filmed them with their cellphones, bringing the lenses in close and squatting to get better angles. The men were kicked in the head. Some of them were forced to reveal their genitals so the attackers could determine if they were Muslim or Christian. All but two of the victims were Sunni Muslims. Some had been beaten to death; others were still struggling to move or breathe. Their bodies, turned to bloody pulps, lay strewn on the ground. The attackers disappeared. Fires continued to crackle inside the building. One of the men still had his shirt pulled up and his pants open. By 5 p.m. eleven men were dead, crushed, beaten, and shot to death. Soon crowds came to view the bodies. Old men and young boys filmed the dead. The Lebanese Red Cross finally arrived, and then the Internal Security Forces and the Lebanese army. The bodies were taken away in ambulances. Army vehicles rumbled into town, taking positions on the streets. As in January 2007, the offices of the SSNP were attacked because it was an easy target with no sectarian base and less immediate consequences. But the SSNP had a long memory and a history of seeking revenge, party members in Beirut warned me. They believed that the mayor of the Akkar town of Fnaydek and his brother were among the leaders of the mob and that the attacks had been ordered by senior Future Party men and Sunni politician and Parliament member Musbah al-Ahdab.