My daughter Tala, a 19-year-old Palestinian who lives in the UK, drew this illustration in May 2021 as our family who lives in Gaza weathered a massive military assault that killed 256 Gazans, including 66 children, and injured and displaced thousands. Tala titled the illustration, “Souls of Gaza, When Children Die,” and wrote the following description:

When children are murdered, words become meaningless... their souls will be looking down upon us

I started working on this piece on the 17th of May 2021. As of that moment, the Israeli settler occupation killed 198 people in Gaza - 58 of them children.

I finished 3 days later. But they were still killing.

As I am writing this it’s 12:00am, and the ceasefire has begun.

I am asking (and I am not waiting for an answer) why are Palestinian children paying this price? Why did innocent people die and the ones left alive were traumatized? Why...? Why did humanity die?

All that’s left is pain... but we Palestinian will continue to have hope... without hope, we will all die.

Tala’s drawing and words speak of longing and grief in the context of witnessing immense violence and experiencing second-hand war trauma. The strong bond my children have with Gaza and the children of Gaza has been nurtured over the course of multiple wars and crimes committed against Palestinian people living in what is often referred to as the world's largest open-air prison. Since 2007 Israel has imposed a land, sea, and air blockade and Palestinians face heavy movement restrictions that make it difficult to travel abroad for work, study, or to visit family.

My story begins in Gaza, my birthplace, but then, like the story of Palestinian dispossession, moves me through multiple places and junctures. I’ve known Gaza before it was under blockade. Israel’s siege on Gaza has devastated its economy. About 56 percent of Palestinians in Gaza suffer from poverty, and youth unemployment stands at 63 percent, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. In 2015 the UN warned that conditions were deteriorating and Gaza could be uninhabitable by the year 2020 after 15 years of blockade. Before moving to the UK, I lived in Ramallah in the West Bank, but I was totally separated from my family in Gaza. This blockade is a form of collective punishment and human catastrophe. Since imposing a siege on Gaza in 2007, Israel has launched four wars between 2008 and 2021. For 11-days in May 2021, the world watched in horror the Israeli military attack on Gaza.

The story of what my family has experienced is the story of many Palestinian families who continue to live under impossible conditions. As difficult as it is for me to witness and comprehend what they are going through, and while being forced by circumstances to live away from them, I take my lead from my daughter as I reflect on their pain, strength, and the love that bonds us to each other and to the cause all of us—young and old, near and far—refuse to lose. I understand this form of storytelling, both in this personal narrative and in Tala’s painting, to be “an archival practice” that, as Palestinian historian Sherene Seikaly describes it, “Weaves stories to shape the present, build connections to the past, and stake claims to the future.” My story and the story of my family become representative of larger Palestinian collective meaning.

Subject to repeated trauma of four wars (ongoing trauma as it is repetitive and chronic), my family has sustained tremendous loss. In 2012, my cousin, Ammen Malahi, lost his life as Israeli rockets targeted the Al-Mograka area. In 2008, a second cousin lost both of his knees and now relies on a prosthesis. In our diasporic home in Britain, we grieved and suffered at a distance, glued to the news, anxiously awaiting updates from our families. Well-intentioned friends relayed their prayers for our families’ safety. But no one is safe. As my mother said to me on the 5th day of the Israeli assault: “We are dying in every moment, and we’d rather die than live in this horror.”

Suspended between hope and grief, we did our part demonstrating on the streets, calling for a free Palestine. Tala and Kareem, my 17-year-old son, did their part, raising funds, marching to the Israeli embassy in London along with 180,000[1] others. These demonstrators articulated the historic complicity of British imperialism in the denial of Palestinian peoplehood and political rights since the Balfour Declaration of 1917. This complicity continues in the present through Israel mobilizes British-made weapons in its war crimes.[2]

My family lives in the Tel al-Hawa neighborhood in Gaza. The household includes my father Najy, my mother Hayat, my brother Muhammed, my sisters Mawadda and Zekra, and their children Rizq, Najy, and Zayna. My brother Reyad and his family live in Chicago in the United States.

My father’s name is Najy, which means survivor in Arabic. He has carried that mantle even under the strain of age, diabetes, and heart disease. On the fifth day of the assault on Gaza, I called him to give him my condolences; he had just lost his best friend Othman Al-Rais in the midst of rocket barrages. His face was pale, his lips dark, and his voice shaky. With a faint smile, he reassured me, “We are fine ya baba, don’t worry.” I struggled with the dissonance. Here I was, in my garden on a sunny spring day in Coventry in the UK, sipping my coffee and listening to birds chirping while rockets polluted my father’s soundscape. I struggled to bridge the gap: “I heard the bad news about your friend, may he Rest In Peace.” I stopped at that word, “peace” and its incoherence for people in Gaza, the impossibility of rest and peace in those spaces of non-choice between slow and immediate death. My father put up a brave response: “He texted me just yesterday, he was fine.” His voice trailed off and he abruptly handed the phone to my sister Zekra. “He’s crying,” she whispered. I have only seen my father cry once, when he bid me farewell before he departed to Gaza. My father’s lifelong companion had succumbed to a heart attack in the midst of intensive shelling. He had no prior health issues and my sister surmised that the agony of repetitive war was too much for him to bear. “Is Baba taking his diabetes medication?” I asked with concern. His supply had run out, and my sister was anxious to refill it, but my father refused; “it’s too dangerous to go out”. When the shelling starts she told me, our father holds his ten-month-old grandchild, Rizq, until it ceases, usually at dawn.

As we spoke, I spotted my second sister Mawadda lying on the floor with only a blanket underneath her fatigued body. Why are you on the floor, I asked? I gave my mattress to the neighbors, who were giving refuge to a displaced family. The wave of the displaced and dispossessed reminded me of the prior war of 2014. Displaced Palestinians were taking refuge in the school next door. People habitually knocked on our door asking for basic amenities: a quick shower and bottles of water. I remembered a pregnant woman at our doorstep in 2014. She was on the cusp of giving birth, but the hospital was so inundated with the injured, the doctors asked her to return in ten hours. Whatever happened to that baby I wondered. Where were they now? Born into war and sustaining yet another? In the midst of my reflections, Mawadda’s strength began to wane. I knew she was pretending to be strong for my sake. She wanted to ease my anxiety, but ultimately confessed: “I’m scared.”

Mawadda is no doubt afraid most of all for her young children. She had Rizq in Gaza, on a visit back home. Since his birth, Rizq has only experienced catastrophe and trauma. When the shelling starts, the baby would put his little arms around my father’s neck and burrows his face in his chest, yearning for comfort and escape. Zayna, Rizq’s sister is 4. The day before the latest Israeli assault on Gaza, Zayna like children throughout Palestine were preparing for Eid. She couldn’t wait to wear her new pink outfit, adorned with a rainbow, and a matching purse embroidered with an orange. I wondered to myself, had Zayna seen a rainbow in Gaza? Zayna is wiser than her years. When the shelling starts her mother tries to convince her it is the sound of firecrackers. But the young four-year-old insists that it is the sound of bombs, and she expresses her fears openly.

My sister Zekra is a warrior on social media, monitoring, reporting, advocating. She falters between hope and despair. Between focusing on the children and getting the word out. At one point, she collapsed from sleep deprivation, only to awaken to the sound of rockets. In the middle of the assault, she went out to pick up some food for breakfast. As the jets hovered and the sound of the collapsing building commenced, she wondered if she would live to eat with her family. Her nine-year-old son, Najy, bears my father’s name and his will to survive. When the shelling starts, he begins to pray and then begs his mother to leave the country. She would assure him, they won’t kill civilians like us. Najy, too, is wiser than his years. Armed with the news from his elders’ phones, he confronts his mother: look, they are killing civilians who are just like us.

My brother Muhammad is thirty years old and has special needs. He suffers in the shelling, hovering near my mother, and taking comfort in her embrace. When I spoke to him in this latest assault, his analysis was crystal clear: enough with wars, he stated, enough with war.

Reyad, my other brother, was my main source of information as my family withstood war. He writes to me from Chicago: You left Gaza twenty years ago. We are now suffering the fourth war in thirteen years. I can’t promise that they will still be alive by the time you get these messages. I know you are looking on in desperation and fear. There are eight of our family in that house. An even number, I often think. They pair up and hold each other, taking shelter in the corridor, rationalizing it as the “safest” place in case the building collapses.

On the fifth night of the war, Reyad learned that the Tel al-Hawa neighborhood was under intense shelling. He anxiously called our mother. She didn’t pick up. He tried Mawadda, she didn’t pick up. He tried Zekra, she didn’t pick up. He even tried our father, notorious for ignoring his phone; he didn’t pick up. Reyad is not one to pray, but he began feverishly pleading with God. He tries again. No one picks up. Reyad feared the worst. A few minutes later, my mother called. Is everyone ok? Reyad asked. “Oh yes,” my mother responded, “We were just having maqloubah.” Distance made me and Reyad assume the worst when our family just doing normal human things like eating dinner.

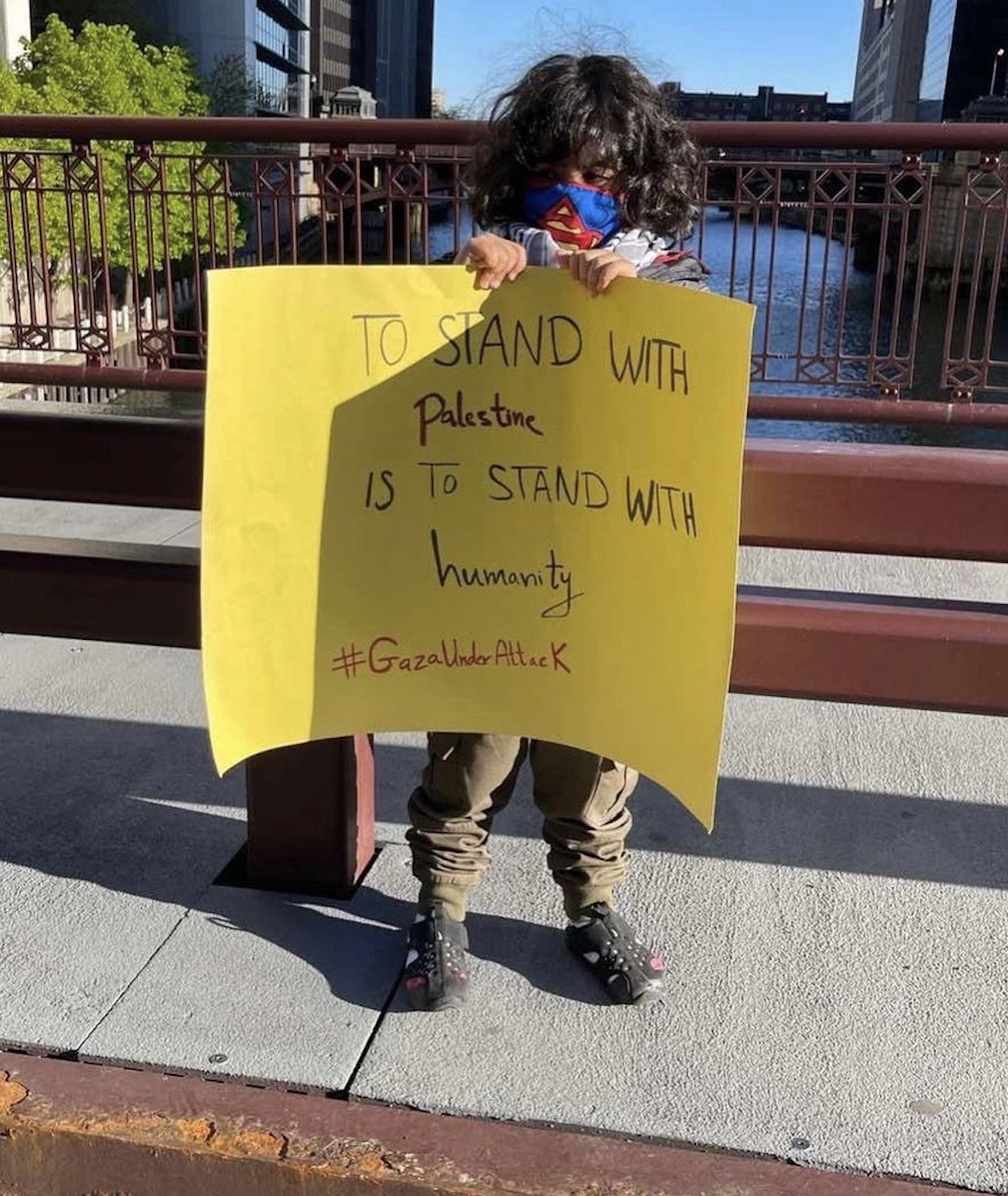

Reyad’s son 5-year-old, Najy, a third survivor, went with his parents to a huge rally in Chicago while his grandparents, aunts, and cousins are under the Israeli bombings. He puts the Palestinian kufiya around his shoulder, a sign in his hand says ‘to stand with Palestine is to stand with humanity’ #GazaUnderAttack.

As I started this personal essay with my daughter’s painting, I end with the image of my nephew’s protest sign. By doing so, I am telling myself, and my readers, that so much hope exists in the work of Palestinian children. Najy and Tala are Gazans, but they don’t live in Gaza. They watch it on the news, hear stories about it, and ask questions about children like them and how they live. We often think of the children of Gaza as casualties, as evidence of Israel’s war crimes. For me, the children of Gaza, inside and outside of it, are young artists, sign-makers, poets, and little protestors. Palestine continues to have a lot to offer. Within and outside its boundaries, to those who can live in it and those displaced from it, children are grown every day to love this place and defend it with all their hearts. Gaza’s children including children in my family are always engaging in storytelling and the archival practice which involves writing for the future. They weave stories not only to shape the present but to create a hopeful future.

Despite the unjust wars and the harsh blows and pain, Gaza is still able to love and resist. As Mahmoud Darwish puts it,

Gaza is not the most beautiful of cities.

Her coast is not bluer than those of other Arab cities.

Her oranges are not the best in the Mediterranean.

Gaza is not the richest of cities.

(Fish and oranges and sand and tents forsaken by the winds, smuggled goods and hands for hire.)

And Gaza is not the most polished of cities, or the largest. But she is equivalent to the history of a nation, because she is the most repulsive among us in the eyes of the enemy – the poorest, the most desperate, and the most ferocious. Because she is a nightmare. Because she is oranges that explode, children without a childhood, aged men without an old age, and women without desire. Because she is all that, she is the most beautiful among us, the purest, the richest, and most worthy of love.

[1] According to the Guardian, organizers estimated that more than 180,000 people marched in solidarity:

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/may/22/thousands-gather-in-london-for-palestine-solidarity-march?fbclid=IwAR0_xU_AE4BcQMVhjeV4PHKbwsnQK-s8pFfIYSFpshgKQsczT4x5ui-z7gA