[On 26 March 2021 the Centers for Middle East Studies at Harvard University and the University of California, Santa Barbara, as part of the yearlong collaborative project “Ten Years On: Mass Protests and Uprisings in the Arab World,” held a roundtable titled “Archives, Revolution, and Historical Thinking.” The persistence of demands for popular sovereignty throughout the Middle East and North Africa in the past decade, even in the face of re-entrenched authoritarianism, imperial intervention, and civil strife is a critical chapter in regional and global history. The following is one of several written contributions elaborating on the discussion addressing the relationship between archives, historical thinking, and revolution—both past and present. Click here to read the remaining contributions to this roundtable.]

On March 25, 2021, the front page of the Francophone opposition paper in Algeria, El Watan, featured the headline: “Historians demand the opening of the archives.” A large photo of the national archives accompanied excerpts from a letter expressing the dismay of Algerian historians who cannot access documents that are “legally available (communicables), particularly those relating to the nationalist movement and the Algerian revolution.”[1] Why is the claim that citizens should be able to consult the historical record on the War of Independence so sensitive? And why has the issue re-emerged at this particular moment?

The demand was made against the backdrop of the Hirak, the popular protest movement that rejected the ruling elite and ultimately forced the resignation of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in February 2019. The fate of this movement is currently uncertain: in late February 2021 activists returned to the streets after public protests were suspended due to the pandemic. In the last few months, the regime seems to have gained the upper hand through a two-pronged strategy of repression and holding elections which are widely seen as illegitimate.

Despite these challenges, there is much to be said about the creativity and resilience of the Hirak. For example, one goal of the protests was to highlight a civic consciousness among the people, something that the government has long claimed was lacking in the country. One way that activists demonstrated this was cleaning the streets after protests (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An image from the Hirak posted on TSA Algérie, 9 March 2019. The article is entitled “Protestor cleaners: “We are cleaning the streets and also the country” [Manifestant nettoyeurs: Nous nettoyons la rue mais aussi le pays].

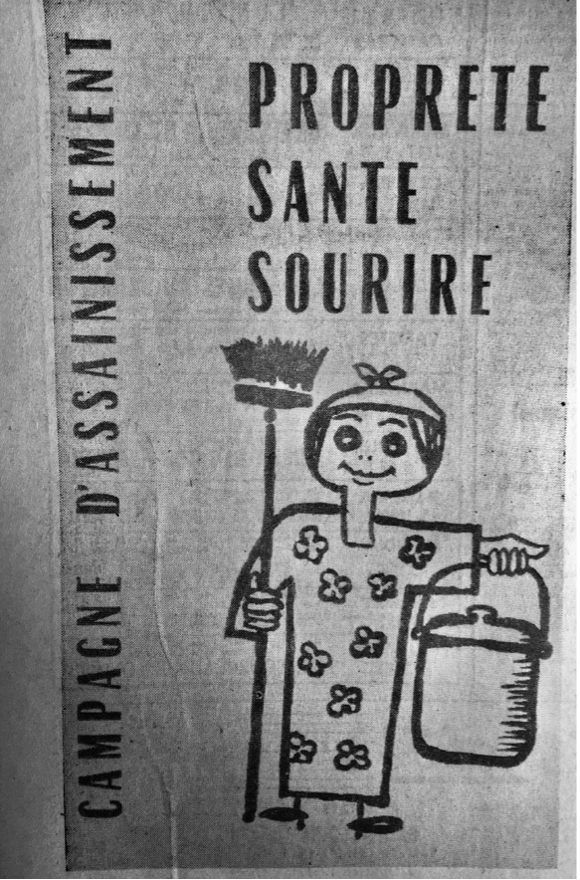

Looking at the images of protestors collecting trash, I could not help feeling that I had seen this trope before. Indeed, in 1965 the Algerian newspaper Le Peuple ran an image in which then-President Ahmed Ben Bella made a connection between cleanliness and the construction of a revolutionary people. It read “cleanliness, health, smile” (propreté, santé, sourire) and depicted a woman with a broom and bucket (Figure 2). Under Ben Bella, the concern with hygiene and the public space was proof of the revolutionary potential of the Algerian people. For the Hirak, however, a similar image was deployed over fifty years later to reject a ruling elite that, in large part, claims legitimacy based on their participation in (or fidelity to) that revolution. As Hirak protestors waged a new movement of contestation, they drew on a shared vocabulary of anti-colonial struggle to make their claims.

Figure 2. An image from the Algerian Newspaper, Le Peuple, no. 84, 16 May 1965. Consulted at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF).

The Algerian War of Independence and the Archive

Even before the Algerian nation-state came into existence, the question of the archive was politically sensitive. In the early 1960s, the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), far right partisans of French Algeria, destroyed the archives of French Algeria as part of their scorched earth policy. They first tried to drown them. When that failed, they set them ablaze.[2] It was not simply an act of resentment, but part of a larger strategy to deprive Algerians of anything that could potentially be useful for constructing a state. Algerians understood this violent destruction as national pillage. Today, the fantasy of archival restitution still looms large. The repatriation of archives, much like that of people and monuments, are acts of national consolidation.

The construction of the Algerian archives after independence was not only about restating a national self, but also about the day-to-day management of the state. The tension between viewing archives as an extension of sovereignty or a tool in routine state management was also central in Franco-Algerian debates after decolonization. Professional archivists made a distinction between those documents that constituted part of France’s history of foreign rule, and those that were necessary for the daily governance and policies of the Algerian states. Algeria may have been part of the French nation, but it was now responsible for its own statecraft; the classification of archives into the categories of sovereignty and management reflected the decoupling of state and nation.[3] Yet this organization of the archive overlooks how the provision of basic state services such as healthcare or the officiation of marriages were indeed powerful tools wielded by Algerians to militate for national sovereignty.

The organization of the archives has been problematic for other reasons as well. Algerians must travel to Aix-en-Provence, where the Archives nationales d’outre-mer—or colonial archives—are located. This is an anomaly in that it treats Algerian history as a chapter in French empire. Yet legally speaking, Algeria was not a colony, but rather three French departments under the purview of the Ministry of the Interior, whose archives are located at the national archives in Paris. By housing the Algerian archives alongside those of “overseas France,” the occupation of Algeria is offered a sanitized place in the (closed) history of French empire, thereby concealing the troubling intimacy between the two territories. In addition, this means that Algerian researchers need significant resources and a French visa to study their own history. While some historians have pointed to the neocolonial underpinnings of the archival status quo, others have defended it in light of the difficulty of gaining access to the National Archives in Algeria.

The legal cornerstone of demands for archival transparency is the law of 88-09. Passed in January 1988, law 88-09 speaks of a state-organized “national archival patrimony.” According to Article 17 of this law, the state is responsible for the conservation of documents. Moreover, the archives “belonged to citizens who can ask for their restitution if they meet sufficient security conditions to ensure their conservation.”[4] This law articulates the relationship between the state, which manages the archives, the nation, whose history can be told through these documents, and citizens, who have a stake in the conservation and organization of this patrimony.

1988 was a year of political crisis that culminated in widespread protests and ended the one-party rule of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). Yet any hopes that the establishment of multiple political parties would lead to a plurality of historical narratives were rapidly dashed. Instead, a military coup and the cancellation of the 1992 elections followed. The ensuing civil war was also a battle of memories—with actors on both sides appropriating the War of Independence.[5]

Following the “Dark Decade,” Algerians were widely disillusioned with formal political parties and the rule of bureaucratic-military elites. Rather than seeing the ballot box as a mechanism for change, the language of political protest was couched in grassroots demands on the state. A signatory of the March 25 letter that demanded archival access, the Algerian historian Daho Djerbal reflected on the Arab uprisings in these terms: “Negotiations between society and the state no longer follow the channels of official parties.”[6] If we acknowledge that the national archives are an extension of state-power, this statement rings especially true in light of the Hirak.

Revolution 1 and Revolution 2

We can think of the Hirak as a revolutionary movement that both relies on, and pushes back against, dominant narratives surrounding the War of Independence. Borrowing from Dipesh Chakrabarty’s notion of History 1 and 2, we might see the two moments as Revolution 1 (the Algerian war of Independence) and 2 (the Hirak).[7]

For Chakrabarty, History 1 occurs in the time of teleological certainty and modern capital. Similarly, the Algerian War of Independence posited the necessity of a centralized, Jacobin state and a unitary conception of the people. Instead of rejecting the historical time of progress, it adapted these structures for its own anti-colonial ends; modernization would be embraced as long as it was in the frame of national (rather than colonial) development, even if the central tenants of developmentalism were largely adopted wholesale. As Robert Malley has argued, the FLN was inspired by a Third Worldist spirit rooted in the belief that the unfolding of history would bring progress and liberation to the global south.[8]

This confidence in the unidirectional march of history, Chakrabarty claims, is nevertheless inhabited by alternative narratives that introduce plurality and indeterminacy, which he terms History 2. This brings to mind the Hirak, which has adopted a strategy of grassroots horizontality. The lack of a specific hierarchy of leadership has perhaps been a hindrance for the movement’s political organization, but it also indicates another mode of political engagement.

Even as Hirak protestors have sought to deconstruct the historical narrative constructed in the wake of the Algerian War of Independence, the movement is undoubtedly a continuation of the hopes and promises of the revolution that gave rise to an Algerian nation-state. The relationship between the Algerian Revolution and the Hirak thus poses a number of questions on the role of the archive and the writing of history, namely: How can the Hirak effectively confront the fact that the current regime has used the War of Independence, and its attendant modes of writing and archiving history, to undermine the current revolution? The ruling elites have long ridden the tattered coattails of Revolution 1. But their revolutionary legitimacy is wearing thin, unraveling in the face of time as well as new modes of political contestation. At the same time, if the Hirak is more accurately described as a revolutionary movement rather than a completed Revolution, this is because the regime has systematically blocked protestors from introducing structural change.

The Weight of Official History

Preserving a dominant narrative of the War of Independence has been central to the current elite, who have tried to instrumentalize the writing of history. In the words of Algerian historian Amar Mohand-Amer, this is evidenced by the transformation of the national archives into a “fortress” to which bureaucrats rather than historians hold the keys.[9] Understanding the archive as a fortress reveals not a deep state, but a hollow one. The historian and former Director of the Algerian archives, Fouad Soufi, points out that the inaccessibility of the archives is less a strategy to conceal secrets than an indication of incompetence.[10] Here, too, the archive reveals the elaborate conspiracies and the glacial temporality of bureaucratic inertia that mark Algerian politics.[11]

The historical re-interpretation currently playing out in the streets seem to find its natural complement in the request for archival access. The current director of the National Archives, Abdelmadjid Chikhi, has argued that the inaccessibility of the archives are needed to maintain the glory of the Algerian Revolution and protect Algerians from the negative effects that any revelations might have on “the evolution of society.”[12] He has also claimed that withholding certain archives from the public is necessary to avoid “compromising” certain individuals and subjecting them to “public prosecution” (la vindicte populaire).[13] This reminds us that the archive is central to the performance of state sovereignty and its ability to police the “boundary between public and private.”[14]

Official channels on both sides of the Mediterranean weigh heavily on the telling of Algerian history. Recently, French President Emmanuel Macron asked Benjamin Stora to write an official report on the Algerian War of Independence, which has inspired countless polemics and critiques. Shown below (Figure 3), the cartoon by Algerian artist Dilem’s depicts the report as breaking the table under its weight; he reveals how acts of state-led historical narratives can only be formalized performative acts. Algerians do not need France to provide yet another account of its colonial crimes.[15] Moreover, there has been no such report issued in Algeria, thus making the notion of a mutual “working through” of historical issues patently ridiculous. As Mohand-Amer recounted in the French newspaper Le Monde: “On one side we have a report that creates a debate after its publication, and on the other a report [expected by M. Chikhi] that creates a debate by its absence.”[16]

Figure 3. Dilem’s cartoon on the Stora report. The French reads “The memory of colonization and the Algerian War – The Stora Report is on Macron’s Desk.” As the report literally breaks the desk, Macron says “It’s the weight of history!”[17]

Algerian historians and citizens currently seek to tell a history liberated from the archival confiscations of both the Algerian and French states. The demand for archival access is therefore a natural complement of the reappropriation of nationalist history that has been occurring on the streets, where protestors have brandished posters of long-marginalized figures such as Messali Hadj or Abane Ramdane.[18]

Given the state’s attempts to impose a hegemonic narrative of the nation’s history, efforts to provide a new “usable past” have occurred outside of official channels. Over the past three years Algerians have used documentaries, personal archives, and literature, to retell their history. This is fundamental for reimagining the nation and creating alternative narratives, but where does it leave the state? What does it mean for the archive as institution? How will these fragments of recovery, especially as related to the civil war, find expression in institutions and structures? These questions, rooted in interrogations about the form and function of the archive, echo broader political dynamics. One of the central challenges facing the Hirak is the need to translate a series of initiatives into an organized movement in the face of a state adept at fragmenting and co-opting politics.

***

Writing in the midst of the Algerian War of Independence, Frantz Fanon noted that in a revolutionary situation, “the past, becoming henceforth a constellation of values, becomes unified with the Truth.”[19] He continued by explaining that “the plunge into the chasm of the past is the condition and the source of freedom.”[20] According to this formulation, history can offer the necessary tools for liberation even if that might imply the risk of reifying national culture. His conviction that a revolutionary future must rely on a reading of the past was also echoed by Hannah Arendt, who described revolution as “a movement back into some pre-established point, and hence a motion, a swinging back to a pre-ordained order.”[21] Today in Algeria, however, the need to protect this “pre-ordained” revolutionary Truth, which was once wielded to achieve national liberation, is now being invoked to prevent historians from accessing the archival record. The question of the archive thus remains suspended between two revolutionary moments; fracturing the ossified narrative of Algerian history is part of the Hirak’s attempt to reopen—and redefine—the possible horizons of emancipation.

[1] El Watan, “Les historiens réclament l’ouverture des archives,” no. 9289, 25 March 2021, 1.

[2] Todd Shepard, “Making Sovereignty and Affirming Modernity in the Archives of Decolonisation: The Algeria-France ‘Dispute’ between the Post-Decolonisation French and Algerian Republics, 1962-2015,” in James Lowry (ed.), Displaced Archives (New York: Routledge, 2017): 57.

[3] Shepard, “Making Sovereignty,” 65-66.

[4] “Ces archives demeurent, toutefois, proprié du citoyen qui peut en demander la restitution s’il justifie de conditions de sécurité suffisante pour leur conservation.” Le Journal officiel de la République algérienne démocratique et populaire [JORA], 27 January 1988, 101.

[5] Luiz Martinez, The Algerian Civil War, 1990-1998 (London: Hurst, 2000)

[6] Muriam Haleh Davis, “Knowledge and Power in Algeria: An Interview with Daho Djerbal on the Twentieth Anniversary of NAQD,” Jadaliyya, 31 January 2012.

[7] Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002).

[8] Robert Malley, The Call from Algeria: Third Worldism, Revolution, and the Turn to Islam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

[9] El Watan, “Les historiens réclament l’ouverture des archives,” no. 9289, 25 March 2021, 3.

[10] Frédéric Bobin, “En Algérie, la révolte des historiens face au verrouillage des archives,” Le Monde, 29 March 2021.

[11] Thomas Serres, L’Algérie face à la catastrophe suspendue. Gérer la crise et blâmer le peuple sous Bouteflika (1999-2015). Paris, Tunis: Karthala, IRMC, 2019.

[12] Frédéric Bobin, “En Algérie, la révolte des historiens face au verrouillage des archives,” Le Monde,, 29 March 2021.

[13] Frédéric Bobin, “En Algérie, la révolte des historiens face au verrouillage des archives,” Le Monde, 29 March 2021.

[14] Jennifer Milligan, “’What is an Archive?’ in the History of Modern France” in Antoinette Burton (ed.), Archives Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History (Durham:: Duke University Press, 2005): 169.

[15] See for example Afaf Zekkour and Noureddine Amara’s comments in Mediapart.fr, “Le rapport Stora vu par deux historiens algériens,” Rachida El Azzouzi, 20 January 2021.

[16] Frédéric Bobin, “En Algérie, la révolte des historiens face au verrouillage des archives,” Le Monde, 29 March 2021.

[17] “Avec le rapport Stora, les poids écrasant du passé frano-algérien,” 22 January 2021, Courrier international.

[18] Muriam Haleh Davis, “The Layers of History Beneath Algeria’s Protests,” December 2019, Current History, 337-352.

[19] Frantz Fanon, “Racism and Culture,” in Toward the African Revolution (trans. Haakon Chevalier) (New York: Grove Press, 1988): 43.

[20] Fanon, “Racism and Culture,” 43.

[21] Hannah Arendt, “Thoughts on Poverty, Misery, and the Great Revolutions of History.” Available online at https://lithub.com/never-before-published-hannah-arendt-on-what-freedom-and-revolution-really-mean/