[On 26 March 2021 the Centers for Middle East Studies at Harvard University and the University of California, Santa Barbara, as part of the yearlong collaborative project “Ten Years On: Mass Protests and Uprisings in the Arab World,” held a roundtable titled “Archives, Revolution, and Historical Thinking.” The persistence of demands for popular sovereignty throughout the Middle East and North Africa in the past decade, even in the face of re-entrenched authoritarianism, imperial intervention, and civil strife is a critical chapter in regional and global history. The following is one of several written contributions elaborating on the discussion addressing the relationship between archives, historical thinking, and revolution—both past and present. Click here to read the remaining contributions to this roundtable.]

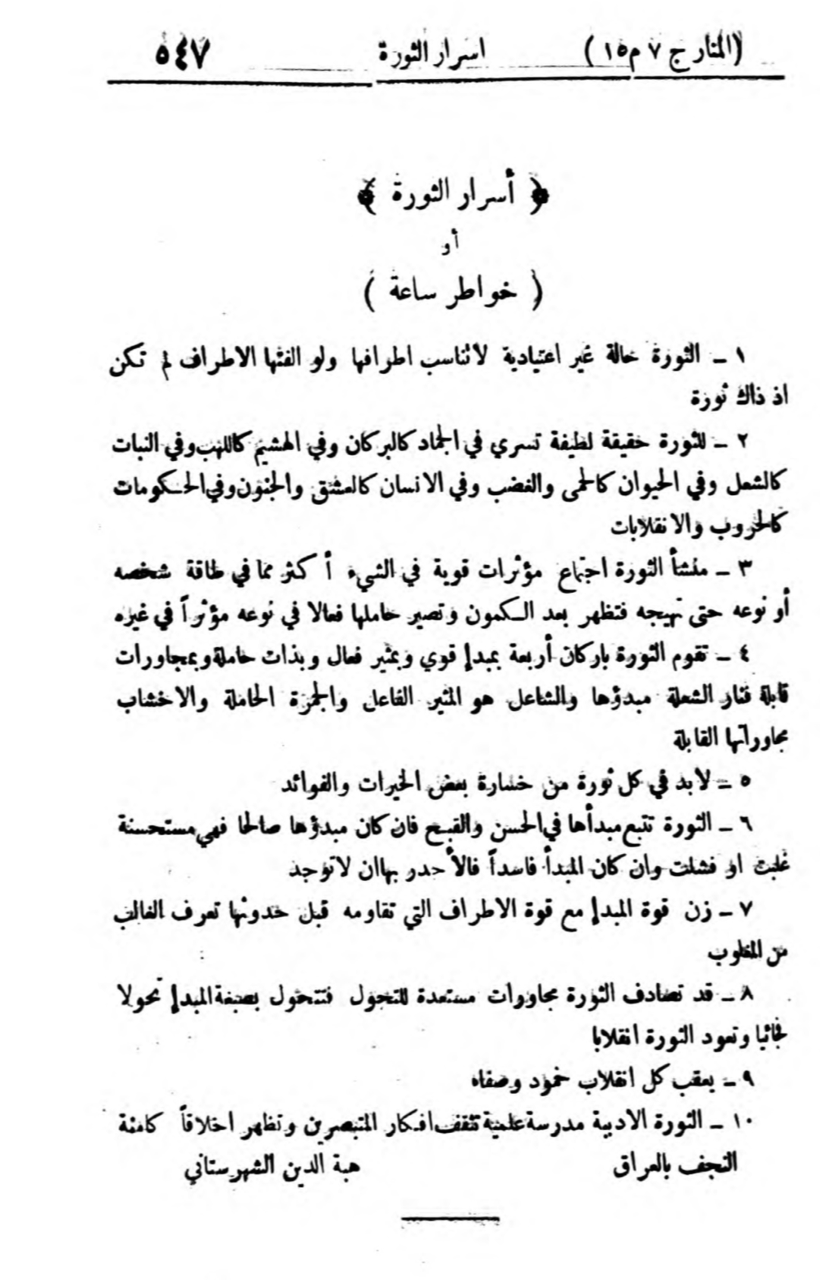

In 1912, the Egyptian Islamic reformist journal al-Manar published a one-page piece on revolution (al-thawra) by a young Shi‘i scholar in Najaf, Iraq (to use the geographical terms in the article’s signature), Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani.[1] The previous year, Shahrastani had shuttered the offices of the first Arabic-language journal to appear in Najaf, al-‘Ilm, which he had edited for two years and modeled on al-Manar and other reformist journals. Around the time the essay appeared, Shahrastani was on his way to India, where he continued to pursue the revivalist, pan-Islamic, and anticolonial projects that had also been among the missions of al-`Ilm. Later, he would become one of the main Shi‘i clerical leaders of the 1920 thawra against the British occupation.

The 1912 al-Manar essay is titled Asrar al-Thawra or “Secrets of Revolution.” Written as a numbered list in language that is both poetic and scientific, it lays out ten secrets, or principles, of al-thawra. The first secret or principle asserts that revolution is an extraordinary and inherently agonistic situation that by definition cannot satisfy all parties. The second describes some of its manifestations: it might start by creeping slowly underground like a volcano, or engulf dry straw all at once in flames, or spread as a fever or rage in an animal, or as love or insanity in a person, or as war or coup/revolution (inqilab) in a government.

The eighth secret elaborates on revolution as a political event: if a thawra encounters propitious surroundings, it may transform into, or return as, an inqilab. In this period, inqilab had not yet settled into its narrower meaning of military coup; here, it seems to refer to an overturning of state power, or what we might call an accomplished revolution. Linguistically, with its sense of overturning, inqilab is closer to the English “revolution” than is thawra. The latter term evokes not a turning but a volcanic eruption. Its continuing political ambiguity, referring to either a successful or an unsuccessful revolutionary uprising, has contributed to much debate on translating the great Iraqi thawra of 1920 into English as uprising, revolt, or revolution.

While the essay does not mention any particular political enemy or context, we can read it in relation to Shahrastani’s other writings around this time. His positive reference to political rebellion usually meant resistance to actual or impending European invasion and possession of Islamic lands. He published statements opposing the 1909 Russian occupation of Iran and the 1911 Italian occupation of Libya. He also frequently predicted the impending British invasion of Ottoman Iraq.”[2] As one reader’s letter put it in al-‘Ilm in 1911: “Time is narrowing and the enemy is at the gates; in fact, he is in the house.”[3] This was not the open, limitless future of modern nationhood described by Benedict Anderson but a future bearing down and closing in.[4]

Shahrastani returned from his travels in 1914, shortly before the British military invaded Basra in November. He immediately joined other Shi‘i clerics on the frontlines of the Ottoman call for jihad. He camped with the mujahidin; acted as a liaison between Ottoman military commanders and Arab tribal leaders; and wrote letters to Indian Muslim soldiers in the British army inviting them to defect from the side of falsehood and join the side of truth. When the resistance was defeated, he wrote that it was an “irreparable loss for Islam” (thalama fi al-islam thalima la yasaddha shay’, literally “it opened a gap in Islam that nothing can close”).[5] For the remainder of the war, Shahrastani stood alongside the clerical moderates, strongly opposing a successful anti-Ottoman rebellion in Najaf in 1915 and, more ambivalently, criticizing a failed anti-British uprising in the town in 1918. By the start of the great Iraqi revolt in the spring of 1920, he was back on the forefront of resistance. When the revolt was suppressed, he was arrested and sentenced by a British military tribunal to death by hanging. He spent nine months on death row in Hilla before being pardoned in the amnesty of 1921, when King Faysal appointed him Iraq’s minister of education, a position he held for a year before resigning in protest against Britain’s continued occupation of Iraq.[6]

In the British colonial archives, the 1920 Iraqi thawra is narrated through a particular kind of historical thinking that continues to dominate scholarship on the event. Based largely on these archives, the central debate in the English-language historiography has focused on whether the revolt was “truly” nationalist or instead driven by local passions and attachments.[7] In the Arabic-language scholarship, which has also been strongly influenced by the colonial archives, the main debate has been over which sociopolitical group was most foundational to the emergence of Iraqi and/or Arab nationalism in Iraq, against the British narrative of incoherence. In both the English- and the Arabic-language literature, nationalism is the frame, whether in its absence or its presence. The thawra is either enclosed within a particular vision of historical time and its ends, the creation of a nation-state, or portrayed as regressive and anti-historical. Both narratives leave unexplored other kinds of anticolonial resources, networks, and sensibilities that the rebels drew on.

The assumption that anti-British resistance was either nationalist or subnational (tribal/sectarian) helps to explain the lack of engagement in Iraq studies with recent scholarship on the “Global 1919” moment, or the wave of anticolonial uprisings sweeping across Asia and Africa at the close of World War I.[8] This absence is especially striking given the size and duration of the 1920 thawra, which has been described as “the most serious armed uprising against British rule in the twentieth century,”[9] and which was preceded by events such as the 1918 anti-British uprising in Najaf. Shahrastani’s prefiguring of anticolonial thawra in his 1912 al-Manar essay, as he set off to establish Islamic revivalist societies in India, is just an example of the kinds of archives that might be assembled if we were to abandon assumptions that for the past century have enclosed the 1920 revolt within national-historical time and state-delimited space.

[1] Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani, “Asrar al-Thawra,” al-Manar 15, no. 7 (1912): 547.

[2] For example, in Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani, Rihlat al-Sayyid Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani ila al-Hind, trans. Jawad Kadhim al-Baydani (Dubai: Dar Madarak li-l-Nashr, 2012), 68.

[3] “Al-`Alam al-Adabi al-Islami,” al-`Ilm 2, no. 4 (2011): 167.

[4] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1983).

[5] Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani, Mu`arakat al-Shu`ayba 1914-1915: Asrar al-Khayba min Fath al-Shu`ayba, ed. `Ala’ Husayn al-Rahaymi and Isma`il Taha al-Jabiri (Baghdad: Mu`assasat al-Sayyid Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani li-l-Tiba`a wa-l-Nashr, 2015), 89.

[6] Biographies include Ahmad al-Bahadili, al-Sayyid Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani: Atharuhu al-Fikriyya wa-Mawaqifuhu al-Siyasiyya (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Fikr al-Islami, 2002); Muhammad Mahdi al-`Alawi, Hibat al-Din al-Shahrastani (Baghdad: Matba`at al-Adab, 1929).

[7] The tone was set by Hanna Batatu’s analysis: “The armed outbreak that this agitation precipitated could not be said to have been truly nationalist either in its temper or its hopes. It was essentially a tribal affair, and animated by a multiple of local passions and interests, but it became part of nationalist mythology and thus an important factor in the spread of national consciousness.” The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq’s Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of Its Communists, Ba`thists and Free Officers. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978), 23. For a counter-argument that it was “first and foremost an Iraqi nationalist revolution,” see Abbas Kadhim, Reclaiming Iraq: The 1920 Revolution and the Founding of the Modern State (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), 52.

[8] For an introduction, see the essays in the “Global 1919” Forum in Journal of Asian Studies 78, no. 2 (2019).

[9] Ian Rutledge, Enemy on the Euphrates: The Battle for Iraq, 1914-1921 (London: Saqi Books, 2014), xxiv. This claim is contestable. For a similar one more plausibly restricted to the interwar period, see Mark Jacobsen, “‘Only by the Sword’: British Counter-insurgency in Iraq, 1920,” Small Wars and insurgencies 12, no. 2 (1991): 323.