The Nation of Islam, or NOI, was founded in 1930 as a politico-religious movement for Black empowerment in the United States. From 1960 onward, it intersected with other US liberation movements under the auspices of Elijah Muhammad, who served as NOI leader from 1934 until his death in 1975. Besides Elijah Muhammad, the NOI’s most famous advocates included heavyweight champion boxer Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, the latter of whom served as official NOI spokesperson until roughly a year before his 1964 assassination, likely by NOI operatives.

The NOI has been studied extensively by scholars interested in the history of race, religion, and politics in the United States during the second half of the twentieth century. Beyond this American context, the NOI’s visual output — such as clothing, apparel, logos, illustrations and documentary photographs — uses symbolic motifs that strategically place the organization firmly within an Islamic register. The NOI’s explicit Islamic imagery formed its identity, especially in its official newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, whose print run of about 800,000 to a million copies per issue circulated between 1960 and 1975. As the scholar Khuram Hussain has shown, Muhammad Speaks was the most widely circulated, Black-operated newspaper in the United States at this time; its visual contents juxtaposed religious and secular imagery important to its Black, progressive readership in highly creative ways.

It is widely known that the newspaper’s reporters were leaders in the Black press, exposing the horrors of the Vietnam War, genocide in Africa, and the lynching and mass incarceration of African Americans in the United States. What is less known is that Muhammad Speaks also served as a major vehicle to promote Islam and to visually present the NOI’s Islamic identity. The newspaper’s “Islamic images” fulfilled three major goals: first, to show Islam as a major unifying creed for self-empowerment; second, to promote Islam as superior to Christianity during the Black Power era; and third, to argue that Islam offers the only means for the Black Man, as imagined in the NOI’s conception, to ultimately unshackle himself from the chains of white supremacy and Christian enslavement.

The Islamic images at the center of this essay count among hundreds that I gathered from over five hundred issues of Muhammad Speaks held in the University of Michigan’s Labadie Collection of print media and memorabilia, produced by anticolonial and antiwar movements as well as civil and labor rights groups. Over the past few years, I also have benefited from lively conversations with my Ann Arbor colleague and neighbor John Woodford, former Editor-in-Chief of Muhammad Speaks, whose voice joins my own in this brief exploration of the Islamic visual culture produced by the NOI during the 1960s and 70s.

The earliest volumes of Muhammad Speaks were a testing ground for the NOI’s calls for self-discipline, economic self-sufficiency, and maintaining one’s health through proper diet, then known by the NOI expression “Do-for-Self.” For Woodford, “Do-for-Self” meant running and improving institutions that “were effective in advancing our people’s status and well-being in the proverbial ‘hells of North America’ or ‘belly of the Beast,’ in the widespread terminology of those days.” This bolstering of the self into economic, educational and physical well-being unfolded in various rhetorical and visual ways, including the newspaper’s masthead and pictorial content, all of which dictated a visual aesthetic and ideological creed for the NOI’s followers.

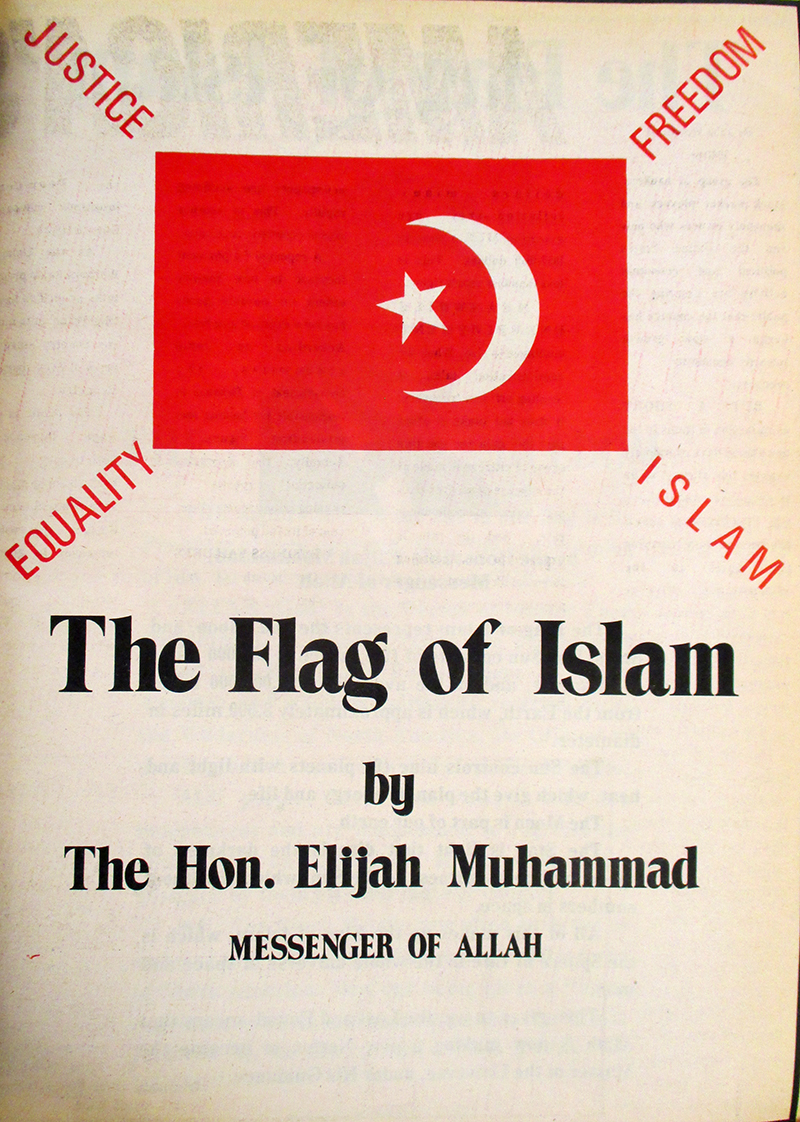

For example, the masthead of the very first issue of Muhammad Speaks, published in May 1960, includes minimal graphic design and simply describes the newspaper as “A Militant Monthly Dedicated to Justice for the Black Man.” Its front page includes a photograph of Elijah Muhammad wearing his jewel-studded fez — his “starry crown” — and a quote from a speech in which he tells his followers that they need to separate themselves and secure their own land in order to achieve freedom, justice, and equality. By 1961, these three ideals migrated into a graphic that came to be known as the “Flag of Islam,” which henceforth appeared consistently in the paper’s masthead and other NOI materials. Inspired by the red flag of the Turkish Republic emblazoned with a crescent moon and star, the NOI’s new logo included in its four corners the words freedom, justice, equality, and Islam (Figure 1). Islam thus was visualized as the last, all-encompassing human aspiration.

Figure 1: Essay by Elijah Muhammad on the “Flag of Islam,” Muhammad Speaks, vol. 10, no. 1, 18 September 1970, special supplement.

Beyond the flag as a symbol of Islamic nationhood, various mottos became central to the NOI’s political message as well. Some were published in the pages of Muhammad Speaks, others broadcast at political gatherings. For example, during his annual convention speeches, Elijah Muhammad would appear at the podium flanked by NOI ministers and his security officers known as “Fruit of Islam” (FOI), which have also been described as the NOI’s paramilitary wing. They were trained in physical combat, searched mosque goers and event attendees for weapons and other prohibited items (like alcohol), and blocked potential assassination attempts. Woodford notes that the FOI indeed had a “reputation for discipline and effectiveness when attacked. On several occasions unarmed members of the Fruit of Islam, the male security force, blunted the assaults of armed hostile police officers.” On a visual level, the all-male FOI members — stern in expression, upright in stance, and dressed in crisp uniforms — embodied the sense of discipline and pride that the NOI wished to project.

Among the various decorative devices used in public gatherings were poster-size photographs that showed Elijah Muhammad holding the Qur’an while banderoles unfurled above him, presenting the Islamic proclamation of the faith (shahada) in English: “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his Apostle.” While one might interpret this statement as the traditional shahada, one of the five pillars of the Islamic faith, it should be noted that Elijah Muhammad’s various titles included “Prophet,” “Messenger” and “Apostle.” The shahada’s second clause thus could be read — and in fact, was read — as an oath of loyalty to the NOI’s leader as “God’s Apostle” (or rasul Allah, in Arabic).

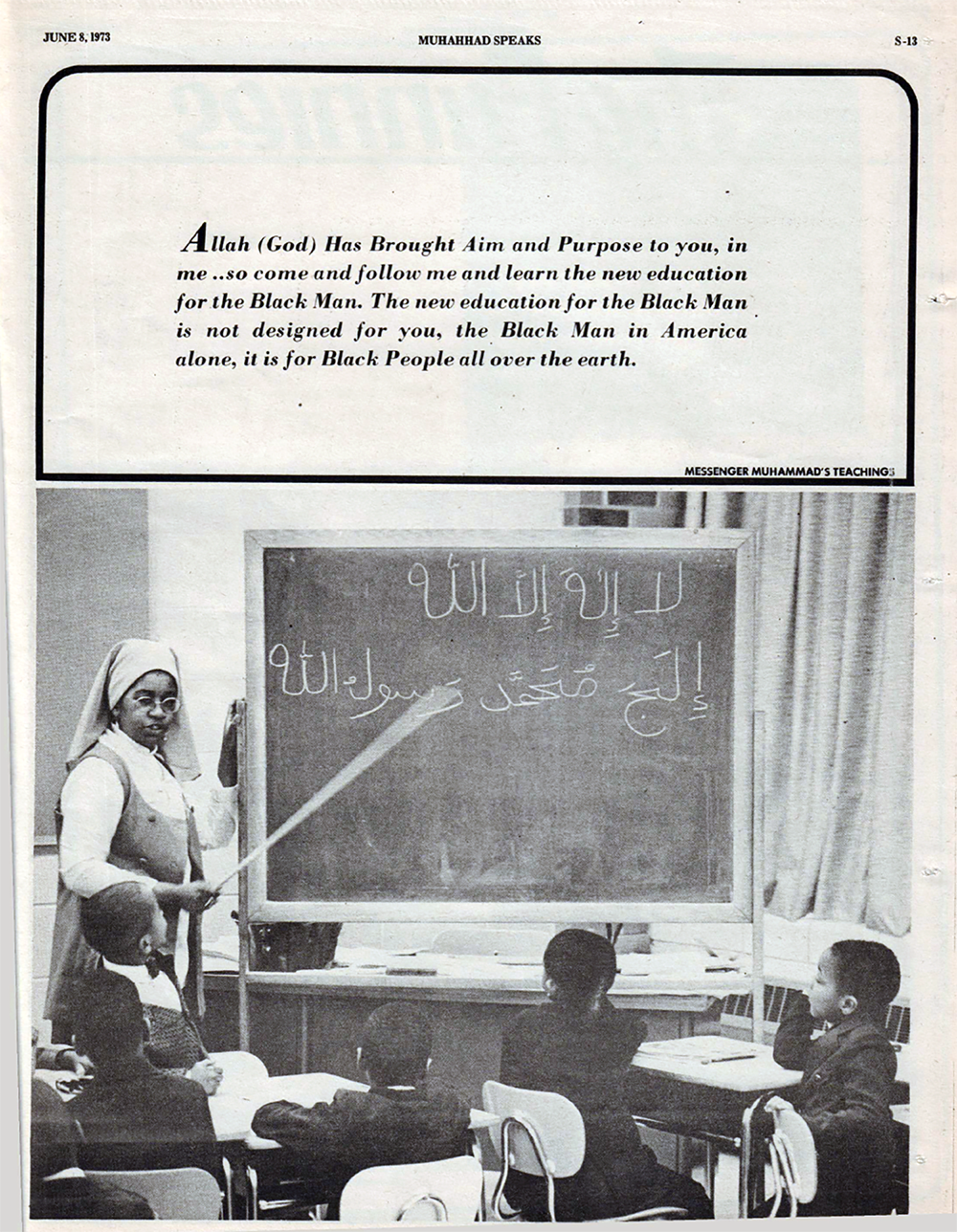

The conflation of Elijah Muhammad and the historical Prophet Muhammad also transpired through the Arabic script, which was taught in the NOI’s schools. Photographs of classroom lessons accompanied articles published in Muhammad Speaks, as can be seen in a 1973 essay touting the NOI’s efforts to implement a “New Education for the Black Man” (Figure 2). Encouraging her young pupils to recite in unison, the instructor points to a chalkboard where those comfortable with the Arabic script can quickly decipher the shahada. However, if one lingers for a moment on the script itself, they reveal a one-word strategic insertion before “Muhammad” that reads phonetically: “i-la-ja.”

Figure 2: The “Elijah-shahada,” included in an essay on “The New Education for the Black Man,” Muhammad Speaks, vol. 12, no. 39, 8 June 1973, supplement no. 13.

The traditional Islamic shahada has been thus expanded to state that “Elijah Muhammad is the Messenger of God.” This is no longer a linguistic hint or innuendo, like the convention banners, but an explicit proclamation that the NOI’s leader is a latter-day rasul Allah. His followers, both students and adults, were encouraged to enunciate a new Islamic declaration of the faith that one might best call the “Elijah-shahada.” This declaration was controversial among many Muslims, who considered the historical Muhammad the last messenger of God. It was also criticized by members of the Black Left, who considered Elijah Muhammad a naive isolationist intent on accumulating wealth through a personality cult. For his part, Woodford, an atheist who was raised as a Christian, notes that the view of NOI followers “was that if the followers of the Arab Muhammad could accept their spiritual leader as the Messenger of Allah, they could accept their Afro-American leader as a successor to that role and title with just as much right and logic as Muslims in the Middle East had asserted for themselves.” The shahada’s alteration thus not only highlights the flexible parameters of the Islamic faith but also helps to track its trajectory within a modern American racialized landscape.

Moving beyond the written word and oral creed, the visuals in Muhammad Speaks portray Islam — and its righteous path of self-determination and economic prosperity — as the antithesis of Christianity, and, by extension, the shackles of slavery and white supremacy.

During the 1960s, the NOI sought to claim political and religious authority through images that depicted battles of good versus evil while promising salvation from subjugation, poverty, and illness. These antagonistic constructs relied on a rich reservoir of religious symbolism as well as categories of thought that positioned Christianity and Islam as ontological opposites. While such binaries continue to thrive in today’s polarized politics, they functioned quite differently in the United States sixty years ago.

Within the context of the civil rights movement, Elijah Muhammad needed to draw Black followers away from his major competitor: Martin Luther King, Jr. Rank-and-file NOI members regarded King “sort of as the head coach of a rival team,” Woodford says. Despite MLK’s cordial relations with Elijah and Clara Muhammad, the ideological divide was represented as if insurmountable within NOI speeches. In plenty of newspaper essays and political artwork, the so-called “Messenger Muhammad” also is depicted as a luminary who is building a Black brotherhood, directly in opposition to the Christian reverend who has submitted to white power. For the NOI, this “either/or” construct served as an existential caveat to “Accept your own or perish,” a politically expedient caveat that appeared in bold print on the cover of a 1965 issue of Muhammad Speaks (Figure 3).

Figure 3: “Accept Your Own or Perish” positing Elijah Muhammad and Islam against Martin Luther King Jr. and Christianity, Muhammad Speaks, vol. 4, no. 37, 6 August 1965.

In other words, Elijah Muhammad warned against Black integration into a white Christian society, promoting Black separatism and self-determination under the salvific banner of Islam instead. The latter two efforts involved securing autonomous land for the purposes of agricultural security and food health, building hospitals and schools, and training a highly skilled workforce to build a technologically advanced future. For their part, NOI graphic artists visually articulated utopian futures and religious dichotomies in which radiant mosques illuminate the future while the decaying body of a crucified Jesus heralds death and destruction.

Binary oppositions are a hallmark of identity-based politics, regardless of time and place. In NOI and other discourses, they help bifurcate hero versus villain, deliverance versus damnation. The same dualism can be presented in side-by-side graphics, such as in illustrations by leading NOI artist Eugene Majied, also known as Eugene X (XX or XXX) or just Majied. Many of his illustrations reiterate this dichotomy by fine-tuning their visual symbolism.

For example, in a diptych entitled “Whom Shall You Serve?,” a Muslim “in-group” is posited against a Christian “out-group” in Manichaean terms (Figure 4). On the left, Majied rhetorically asks his viewers whether they shall serve Satan and illustrates a decrepit church over whose entrance is inscribed “White Man’s Slavery.” A hunched-over Black man follows in the tracks of affluent Christians decked in fur coats and top hats, while a smoldering sky engulfs the necrotic body of Christ nailed to the cross. With a bridging ellipsis to the right frame, Majied proceeds with an alternative query: namely, whether his viewers are willing to serve God. Here, a domed mosque whose entrance is emblazoned by the Flag of Islam and the inscription “God’s Freedom” welcomes a row of Muslim faithful — including NOI women clad in their distinctive white robes and hijabs — who make their way into a luminous architectonic stand-in for deliverance from white supremacy and Christian oppression.

Figure 4: “Whom Shall You Serve?,” illustration by Eugene Majied, Muhammad Speaks, vol. 3, no. 26, 11 September 1964, p. 5.

This pair of either/or putative opposites is not just shown as a mutually exclusive proposition. For the NOI, this comparison pushes forward historical Islamic religious declarations while also echoing modern American political speeches. From within the emic Islamic tradition, these illustrations level accusations of disbelief (takfir) while proclaiming a loyalty to Islam and a disavowal of Christianity (al-wala’ wa’l-bara’). Not limited to Islamic religious spheres alone, excommunication, adherence, and repudiation are also typical of polarized political environments — in this case, the fraught landscape of the 1960s United States. To gain adherents, the NOI — like many other organizations and movements past and present — pitched a stark black-and-white choice that rejects a third position or neutral middle ground.

For Elijah Muhammad and his followers, this choice was couched as an existential one. It symbolized the yearning for an irrevocable release from the centuries-old shackles of Transatlantic slavery and anti-Black racism in the United States. Additionally, Woodford says that “Elijah Muhammad felt Christianity imposed feelings of submissiveness, inferiority, and shame in a people whose ancestors had been brought here forcibly as slaves by Christians, and were then subjected to laws and a culture that abused and degraded the Black ethnic group. Freeing them from Christian doctrines, he felt, was a necessity if they were to overcome the false consciousness enforced by the country’s dominant ideology of white supremacism.”

In the NOI’s worldview, only Islam could offer the key to a final release from various forms of bondage — educational, economic, psychological, physical, social, or political. For these reasons, the Muslim faith, its diverse corpus of ideas and symbols, and its unifying lexicon were telescoped into a larger emancipatory project. This great unchaining was depicted through the Muhammad Speaks illustrations printed during the 1960s and 70s.

The larger struggle of emancipation is frequently represented through a clenched fist and muscular forearm — the twin symbols of physical labor and social uprising — attempting to rend a metal chain. Drawing upon the imagery of slave shackles, the chained manacles in NOI visual culture picture a legacy of fear that only Elijah Muhammad could abolish once and for all (Figure 5). The occasional inclusion of Qur’anic and Biblical references in such graphics helps the viewer interpret these images through holy scriptures, leveraged to promote the NOI’s message. For example, one image mentions Revelation 21:8, a verse in the Bible that lauds New Jerusalem as the eternal home of believers. For Elijah Muhammad, Islam indeed offered a new promised land delivering liberty and opportunity since, as he argued, “a people guided by Allah cannot be enslaved.”

Figure 5: Elijah Muhammad breaking the chains of fear, Muhammad Speaks, vol. 8, no. 17, 10 January 1969, front page.

Beyond citing slavery’s physical and psychological ruinations, NOI illustrators employed the chain motif to advance other political discourses, particularly that of Islam as the uniting force for Black communities around the world. Within the United States, the pressures exerted upon this international bond of fraternity were considered twofold. First and foremost, NOI visuals display the efforts of the U.S. government — often visually represented by Uncle Sam wearing his top-hat — to sever the cable of pan-African solidarity, thereby ensuring the continuation of white supremacy around the globe. Moreover, during the 1960s, according to the NOI, the second threat to this solidarity was none other than the so-called “Black preacher,” a figure who is time and again lambasted as an integrationist traitor and the community’s weakest link (Figure 6). This figure of the Christian minister is not only a generic prototype but often a direct reference to Martin Luther King, Jr., whom Malcolm X described as a “religious Uncle Tom” keeping the Black man from achieving freedom, justice, and equality under Islam. This stark criticism was leveraged as a rhetorical and visual tool of recruitment to the NOI.

Figure 6: “Islam Unites,” illustration by Majied, Muhammad Speaks, vol. 6, no. 16, 6 January 1967, p. 2.

Additionally, the redemptive discourse of the NOI resulted from several interrelated objectives, namely a release from Christian domination as well as real and metaphorical forms of captivity. Elijah Muhammad’s speeches often referred to the salvation of the “Black Man of America,” including on the front page of a 1967 issue of Muhammad Speaks that depicts an individual attempting to escape the fiery “wilderness of North America” — that is, a place of perdition and savagery “to which one came only against one’s will,” far away from the African diaspora’s original civilizational home. A Black man is shackled to the heavy cross of Christianity while Elijah Muhammad runs towards him, armed with an oversized golden key and clamoring: “I’m coming…I have the key!” (Figure 7). Here and elsewhere, Islam is promoted as freeing Black bodies from the fetters of Christian supremacy and slavery’s after-effects.

Figure 7: “I’m Coming…I Have the Key!,” Muhammad Speaks, vol. 6, no. 24, 3 March 1967, front page.

But the so-called “Islam Key” also signified, much more literally, a liberation from American jails, where a disproportionately large population of those who were incarcerated were (and still are) Black. Journalists at Muhammad Speaks were at the vanguard of exposing systemic racism in the US prison system more than half a century before loud calls for decarceration started to become mainstream. The newspaper regularly included a section entitled “What Islam Has Done For Me,” which featured letters by individuals who embraced the faith while behind bars. Editors at Muhammad Speaks, Woodford tells me, selected those letters that:

reported on how joining the NOI had put the prisoner on a path of personal self-control, spiritual improvement, and intellectual development. The news staff usually focused on prisoners who described abusive practices in the prison and biased actions aimed at Muslims in particular, such as denying them access to reading materials or to medical care, to cite only a few of myriad indignities.

These prisoners often wrote that they found personal rehabilitation and a sense of purpose in life thanks to the NOI’s national prison Muslim chaplaincy program, which remains active today.

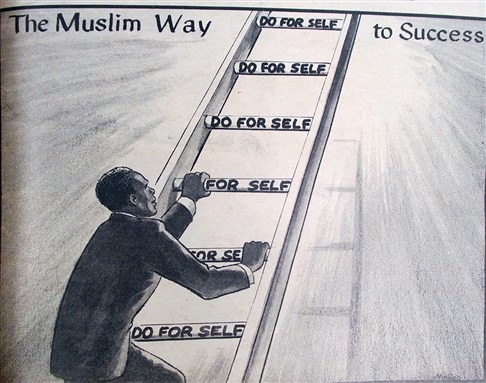

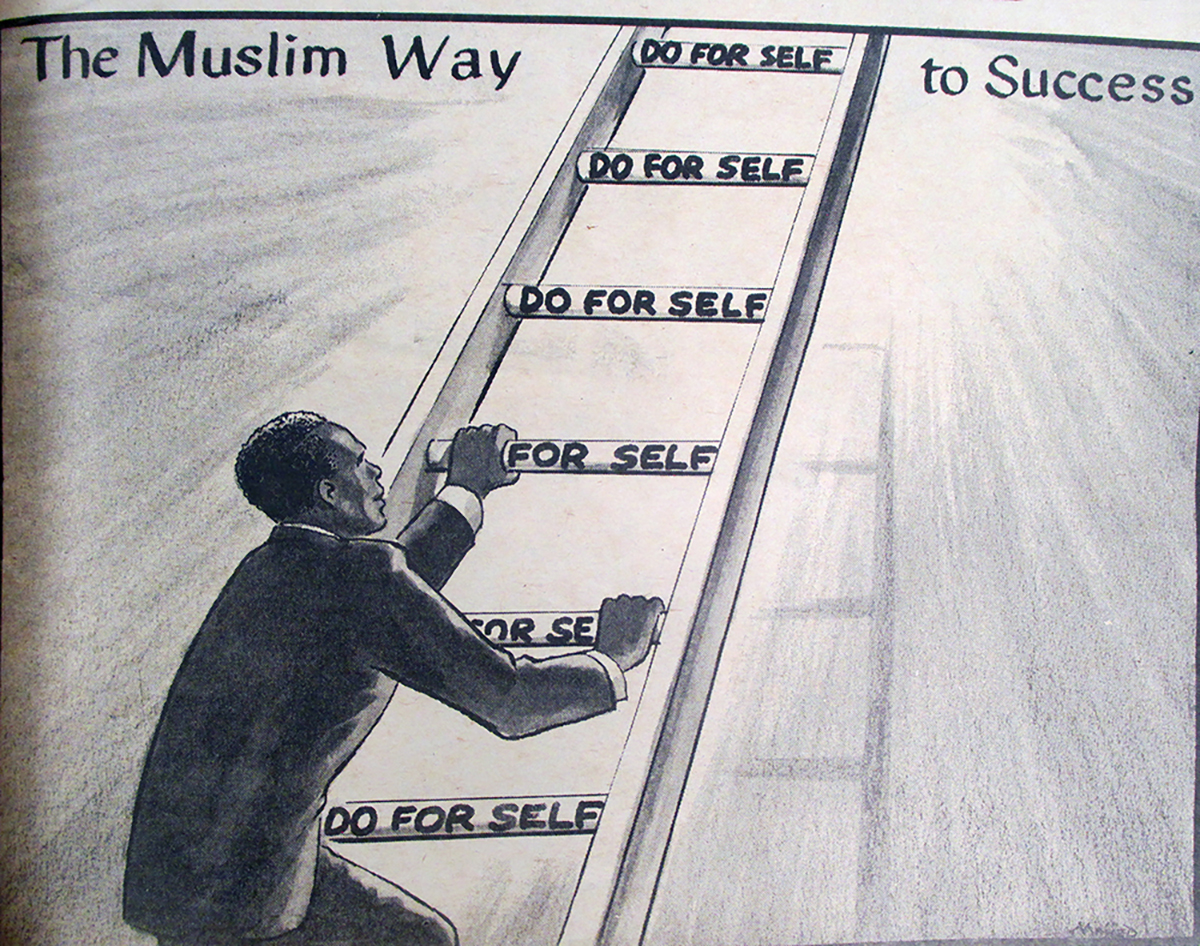

Such accounts were also visually represented, including in illustrations by Eugene Majied that showed Elijah Muhammad’s arm holding the “Islam-key” as he unlocks a jail door. In the NOI’s conceptual framework, this emancipatory rhetoric provided a total package for personal deliverance and community empowerment: a Muslim pathway to success, which within NOI visuals took the recurrent form of the “Do-For-Self” ladder (Figure 8). This ascent was shown as promising a freer present, and a more promising future, for Black communities in the so-called “hells of North America” and “belly of the Beast.”

Figure 8: “The Muslim Way to Success,” illustration by Majied, Muhammad Speaks, vol. 8, no. 8, 8 November 1968, front page.

In sum, Islam offered an alternative vision for Black communities during the 1960s and 70s. At that time, the NOI participated in the rise of Black consciousness while, as Woodford emphasizes, its spiritual steward Elijah Muhammad tended to the task of “refashioning, reinterpreting, and repurposing Islam to construct that alternative vision.” Through its visual imagery, Muhammad Speaks also articulated an Islamic-ness that lambasted the racist legacies of the United States while concurrently stretching the frontiers of Islamic art and visual culture to encompass modern America.