[Bu yazı, Jadaliyya Türkiye Sayfası Editörleri tarafından hazırlanan “Gezi'yi Hatırlamak: On Yıl Sonra Nostaljinin Ötesinde” başlıklı tartışma serisinin bir parçasıdır. Konuk editörler Birgan Gökmenoğlu ve Derya Özkaya tarafından hazırlanan serinin giriş yazısına ve diğer makalelerine buradan ulaşabilirsiniz.]

Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu (YKF), 2013 yılında Gezi direnişinin hemen ardından İstanbul’un farklı semtlerinde kurulan park forumlarından günümüze kadar aralıksız devam eden, tüm kadınların katılımına açık, bağımsız bir forum. İlk olarak 26 Haziran 2013 tarihinde Kadıköy Yoğurtçu Parkı’nda toplanan forum, o günden itibaren her hafta Çarşamba akşamları foruma katılan kadınların ortaklaşa belirlediği gündemlerle, feminist ilkeler etrafında bir araya gelmeye devam ediyor. YKF, Gezi direnişinin kolektif hafızasının bir parçası olduğu gibi Türkiye’de feminist hareketin/kadın hareketinin önemli öznelerinden biri olarak yoluna devam ediyor.

YKF, 21 Haziran 2023 tarihinde, “Trans çalışmaları: Cinsiyet ve bilim” adlı kitabı tartışacağı forumunu polis ablukası nedeniyle gerçekleştiremedi. Kadın+’lara ve LGBTQI’lara karşı işlenen nefret suçlarının arttığı bu günlerde, bir araya geliş hikayelerini ve yürüttükleri faaliyetleri kendilerinden dinlemek için sözü Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu’na bırakıyoruz. Aralarındaki kesişimler dolayısıyla YKF’yle ilgilenen okuyucularımızın bu sayı kapsamında Çatlak Zemin[1] hakkında yaptığımız söyleşiye de göz atmalarını öneririz.

***

Biz on yıldır memlekette ve dünyada kadınların gündemini izlemeye ve müdahil olmaya çalışıyoruz. Miladımız olan 2013’ten bu yana çok alametler belirdi, çok şeyler değişti ama sömürü gibi, şiddet gibi ezeli ve ebediymişçesine duran patriyarka, değişmemekte ayak diredi. Olsun… Biz eteklerimizdeki taşlarla, üzerimize kapanan duvarlarda delikler açmaya, buralardan soluk almaya çalışıyoruz. Biliyoruz, birlikte ve bir arada olmak gerekiyor duvara yüklenmek, onu yıkıp geçmek için…

Derya ve Birgan Gezi’nin 10. yılı vesilesi ile hazırladıkları dosya için aylar öncesinde Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu'nun (YKF) kendini anlatması için bizimle iletişime geçmişti. Ancak 2023 Şubat ayında yaşadığımız depremlerin, yıkımın üzerimizden atamadığımız etkisi ve bölgeyle, bölgedeki kadınlarla dayanışma gayesi ile bu anlatı biraz ertelendi. YKF’de duyurusu yapıldıktan sonra kurulan küçük komisyonda haftada bir toplanarak bu yazıyı hazırladık. Efendim YKF, övünmek gibi olmasın ama… Dünyada eşi benzeri olmayan bir oluşum olduğu için bu yazıyla tarihe ve tarihimize bir not düşmek istedik. Lessing’in dediği gibi; “kadınlar çoğu zaman hafızalardan, sonra da tarihten silinip gitmesinler” diye…

Baştan başlayalım, en baştan. “Gaz ve toz bulutu idi her şey önce” gibi olacak ama…

Feministlerin Gezi Park’ına kurduğu mor çadır etrafında toplanan kadınlar ve LGBTİ+lar olarak bu sürecin nasıl yaşandığını konuşmak üzere İstanbul Feminist Kolektif’in (İFK) çağrısı ile 26 Haziran’da Anadolu Yakası’nda Yoğurtçu Parkı'nda, Avrupa Yakası’nda da Maçka Parkı'nda bir araya geldik. O günden bugüne devam eden tek kadın forumu olan YKF'yi, yapılan bu çağrıyla bir araya gelen kadınlar olarak bağımsız bir örgütlenme şeklinde devam ettiriyoruz.

Ve hikayemiz sürüyor, ilk 10 yılımız bitmek üzere… (Nice nice on yıllara)

Yoğurtçu Parkının yeşil çimenlerine çok yakışan mor örtülerimiz, şimdiye kadar kaç yaz, kaç onlarca forum, atölye gördü kim bilir? Biz biliriz elbet. Dilimiz döndüğünce birkaç kelam etmeye çalıştık biz de.

26 Haziran 2013'ten bugüne her Çarşamba, yazları Yoğurtçu Parkında, kışları bize mekanını açan dayanışmacı bir dernekte, kadınların hayatına dokunan her şeyi gündemimize aldık ve almaya da devam ediyoruz Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu’nda.

Forum günlerimizde yeri geldi mahalle örgütlenmelerini konuştuk[1], mahalleleri kadınların daha rahat ve güvende hissedebileceği yaşam alanlarına dönüştürmek için talepler ürettik. Sokak lambalarının ışıklarını azaltanlara karşı dayanışmamızla aydınlatmak istedik sokakları.

Yetmedi, “Oyumuz kadınlardan yana bir Kadıköy için” diyerek Bahariye Caddesi’ndeki Süreyya Operası önünde yaptığımız eylemle, Kadıköy Belediyesi’nden istediğimiz talepleri de sıraladık: Kadın sığınağı, ücretsiz kreş, bakımevi, çamaşırhane, kadınlar için acil durumlarda 7/24 açık kriz masası, göçmen kadınlara barınma desteği…[2]

Hızımızı alamayıp 1 yıl sonrasında Kadıköy Belediyesinin Yerel Eşitlik Çalıştayı’nda bulduk kendimizi. Mahallemizi, yaşam alanlarımızı konuşmaya, sorgulamaya ve dönüştürmek için çabalamaya devam ederek 2019’da yine yerel yönetimlerden beklentilerimiz üzerine konuştuk, “2014 seçimlerinden önce adaylara ilettiğimiz taleplerden hangilerinin uygulamaya konulabildiğinin” peşine düştük.[3]

Çarşambalar çarşambaları, aylar yılları kovaladıkça “Gezi'den sonra bir araya gelip sonra da birbirini bırakmamacasına başlayan ve her seferinde yeni dostlarla büyüyen kadın forumumuzun” yıldönümlerinde, yılbaşlarında bir araya geldik. Hep birlikte olmak, birlikte gülmek, “afedersiniz” birlikte kahkaha atmak, geceleri de sokakları da bırakmamak üzere birbirimizden enerji bulmaya çalıştık. Çünkü “Kötülüğün bu kadar sıradanlaştığı şu zamanda bir arada olmamız, kadın bedeni/emeği üzerinde bu kadar tahakküm kurmaya çalışanlara karşı ‘buradayız’ deyişlerimiz, kadın direnişimiz güçlendiriyor hepimizi” demiştik bir kere.[4]

YKF’de dünyadaki diğer kadınlarla birlikte gündemlerimize, patriyarka ve kapitalizmle olan mücadelelerimize perde açtık forumlarda. OHAL ilan edildiği 2016’da “Ortadoğu’da direniş, darbeler ve bu koşullarda kadın olarak nasıl var olduğumuz”dan[5] Güney Afrika’da kadınlara ve LGBTİ+’lara yönelik erkek şiddetinin can yakıcılığına[6], Ortadoğu ve Kuzey Afrika'daki feminist mücadeleden[7] kadın kurtuluş mücadelesi tarihinin Batı Almanya’daki örneği Rote-Zora’ya[8], haklarımıza saldırıların, nefret söylemlerinin, ırkçılığın yükseldiği, bunun yanında eylemler, direnişler ve mücadelelerin de yoğunlaştığı 2022 yılında Afganistan, İskoçya, Arjantin, Fransa, ABD, Polonya, Pakistan ve daha birçok ülke ile dünyanın dört bir yanından kadın mücadelelerine…[9]

Tarihe de el atmışken bastık zaman makinesinin “götür bizi istediğin yere” düğmesine.

YKF’nin kendi tarihinde/tarihimizde dolaşırken neler yaptığımıza, neler konuştuğumuza, nelere ses çıkarıp isyan ettiğimize göz attık.

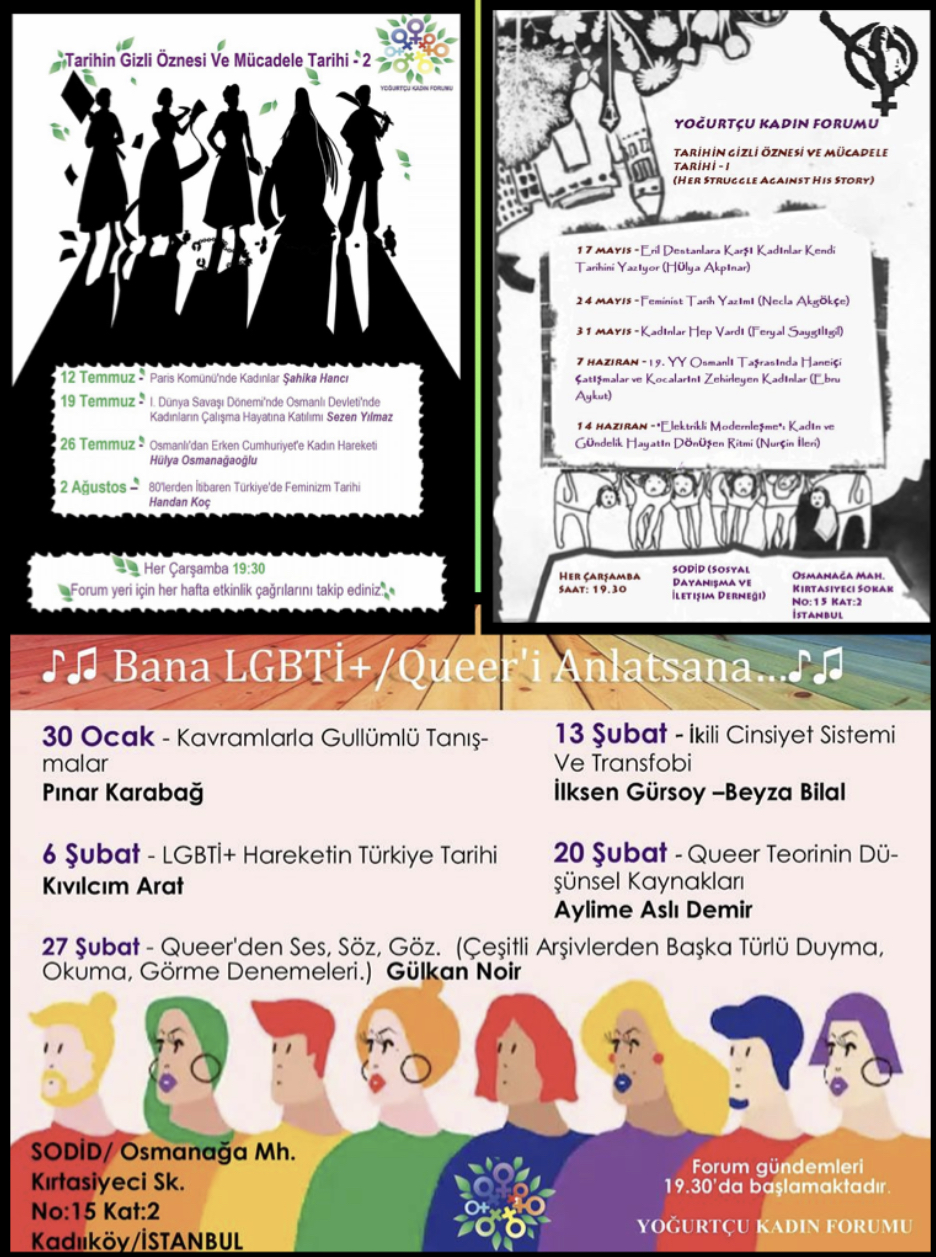

Bu 10 yılda sadece forum gündemleri yapmadık mesela. Yeri geldi hem dayanışmayı büyütmek hem de dayatılan tüketim çılgınlığına karşı koymak için takaslar, mezatlar yaptık[10]. Yetmedi, ihtiyaç duyduğumuz çeşitli atölyeler düzenledik. Bu atölyelerde kimi zaman, erkek şiddetinin bir aracı haline dönüşebilen küfürler üzerine düşündük kimi zaman politik bir mekanizma olarak teşhir-ifşa yöntemini kurcaladık.[11] Bazen nefes almak; kendimizi, zihnimizi dinlemek, dinlendirmek istedik ve stencil, kartpostal ya da kokedema atölyelerine atıldık.[12] Bir soluklanmanın ardından da çeşitli serilere giriştik: Psikoloji, queer, tarih…[13]

“Aşk” ı hiç ihmal eder miyiz, etmedik tabii… Masallarda, tragedyalarda, mitolojide, yapay zeka evreninde izini sürdük; romantik ilişkilerin evrelerine, ilişkilenme biçimlerine, psikanalitik, hümanistik yaklaşımlara varıncaya aşkı konuştuk. Feminist psikoloji serisi ile kadının mağdur, travmatize, acı çeken, tek tip profiline karşı sorunun aslında erkek egemen bir çevrede yaşamaktan kaynaklandığını, yani kişisel olanın politik olduğunu bir kere daha gördük.[14]

Queer… Normun dışından bakmaya, duymaya, olmaya kafa yorduk, birlikte düşündük. Queer’in düşünsel kaynaklarını, sanata yansımasını konuştuğumuz forumlarda feminizmle, toplumsal hareketlerle ilişkisine, queer siyasete ve siyasetin queer’leşme olasılıklarına baktık.[15]

Patriyarkanın en gözde nüfuz alanı tarih; tarih aynı zamanda kadının varoluş mücadelesi verdiği en geniş kulvar. Eh, hal böyleyse tarihi baştan yazmak, geçmişi güncellemek, emeğimize sahip çıkmak boynumuzun borcu.

Eril tarihin tekerrürden ibaretliğine karşı (aman ne sıkıcı) mücadele ile dolu kadın tarihi. Kendi tarihimizi kendimizden dinlediğimiz, tarihi dönüştürmenin, geliştirmenin yollarını birlikte aradığımız, erkek egemenliğin üretmiş olduğu tarihlere karşı bilgi, gerçeklik, algı ve hafızamızı açtığımız forumlarda Osmanlı’dan erken Cumhuriyete, 80’lerden günümüze feminist hareketin, kadın hareketinin tarihine daldık.[16] Eril destanlara karşı kadınların kendi hikayelerini yazmalarının önemini biliyoruz, bir kez daha bunun önemini kavradık.[17]19. yüzyılda Osmanlı taşrasında haneiçi çatışmalara pencere aralarken kocasını zehirleyen kadınların hayatına çevirdik fenerimizi. E, fenerimiz var madem, elektrikli modernleşme ile kadının gündelik hayatının dönüşen ritmine de bakmasa mıydık?[18]

Tarih içinde tarihe doğru yol aldıkça Selma Rıza’larla, Sabiha Sertel’lerle, Semiha Es’lerle tanıştık. Zabel Yeseyan’la bir kahve içelim, Yaşar Nezihe ile hoşbeş edip şiirler düzelim, Zehra Kosova ile “Ne olacak bu sendikaların hali?” ile başlayıp politika konuşalım derkeeeen… Bir baktık 1870’lerin Paris’inde, komünün merkezinde direnen kadınlarla omuz omuza mücadele içindeyiz.[19] Bir baktık Osmanlı sokaklarında, hanelerinde, fabrikalarında ter dökerken “ben de varım” seslerine ortak oluyoruz. Hoop ordan Güney Amerika’ya, ön safları kadınların tuttuğu masalsı direnişleriyle hepimizi heyecanlandıran Zapatistalara…[20]

Bir sonraki durakta kendimizi “ilk” dalganın üzerinde bulurken yüzyıllardır varlığını saçımızdan tırnağımıza, gülüşümüzden cinselliğimize hissettiren patriyarka karşısında, yine yüzyıllardır farklı isimlerle, çehrelerle ama hep mücadele eden kadınlarla, feministlerle karşılaştık, selam çaktık, sarıldık, seviştik. Yeri de gelmişken efendim, söylemeden geçemeyeceğiz. Cinselliğimizi, hazzımızı elimizden almak isteyen erkekler bir kenara çekilsin hele; biz kendi bedenimize bakmanın, hazzımızı sahiplenmeni peşine de düştük. Neymiş bu seks oyuncakları yahu diyerek bir de böyle oyuncakları keşfedelim dedik.[21]

Ah zaman da makinesi de durmuyor a canım.

Hop geldik, kendimizi bir güzellik yarışmasında bulduk. Bulduk bulduk da “1929-33 yıllarında düzenlenen güzellik yarışmalarında ırkçılığa doğru hızla ilerleyen Türk milliyetçiliğini, üçüncü dünya ülkesi olmayı yedirememenin dayanılmaz sancısını, Avrupa medeniyetine dönük aşk-nefret ilişkisini ve Osmanlı’dan kopuşu ispatlama isteğine” de tanıklık ettik. Ardından geldik karma örgütlerde, sendikalarda, odalarda yer alan kadınların mücadelesine.[22]

Tarihte, hanede, sokakta, siyasette, odalarda modalarda, bulunduğumuz her alanda kendimizden, birbirimizden, mücadelemizden, mücadele tarihimizden güç aldık hep. Çünkü “Erkekler yüzünden asırlarca hatta dünya dünya olalı çekmekte olduğumuz zulmün defini (defedilmesini) bugün biz erkeklerin mürüvvetinden (iyiliğinden) istemeye tenezzül eder miyiz?”[23]

Etmeyiz be canım.

Kimi zaman (hatta çoğu zaman) üstümüze kara bulutlar, tek adamlar çöktü. Kadın ve LGBTİ+ düşmanı politikalarıyla, ırkçılığıyla, savaşıyla; haklarımıza, İstanbul Sözleşmesi'ne, 6284'e saldırılarıyla peşimizi bırakmadı da bırakmadı. Hayır dedik, “Geleceğimizi tek adam rejimine teslim etmeyeceğiz”!

“Biz kadınlar geleceğimizi, özgürlüğümüzü, yıllardır mücadelelerimizle sahip olduğumuz kazanımlarımızı tek adam rejimine teslim etmeyeceğiz!” dedik, dedik, 2017’de başkanlık referandumunu da masaya yatırdık.[24]Üstüne, tüm höt höt konuşmalara karşı biz de “bilir o kendisini” diyerek bir şarkıyı uyarlayıverdik, düm tek tek, çıkı çıkı çıkı çıkı:

“Son verdi meclisin işine

Hayır diyoruz biz bu işe

Son verdi meclisin işine

Hayır deyin onun dikta rejimine

Her gün yeni bir dert açıyor

Kendini bilmem ki ne sanıyor

İsyandayız ve de kararlıyız

Tüm hayır diyen kadınlar

Barıştan yaşamdan yanayız biz

Feminist isyanda hep kararlı duruş

Barıştan yaşamdan yanayız biz

Feminist isyanda kararlıyız.”

Çiki çiki çiki çiki, oh oh.

Patriyarkanın, erkek devletin, şiddetin, sömürünün karşısında söz ürettik, yeri geldi şarkı yazdık-söyledik, yeri geldi hayır’larımızı haykırdık, sokakları meydanları terk etmedik. Haklarımızın erkekler ve iktidar tarafından gasp edilmesine, kadına yönelik erkek şiddetine, tacize, tecavüze karşı sesimizi hiç kısmadık ki. Erkek şiddetine karşı 8 Mart’larda, 25 Kasım’larda, sokaklarda eylem yaparak haykırdık, failleri ifşa ettik. Kadına yönelik şiddeti, bu şiddetle mücadele mekanizmalarını konuştuk.[25]

Bunca saldırının, şiddetin, kadın ve LGBTİ+ düşmanı politikaların, cezasızlığın, savaş çağrılarının, pandeminin, ekonomik krizin, KHK'ların yarattığı yıkımın ortasında hiç mi umutsuzluğa kapılmadık? Kapıldık. Üzüldük, yalnız hissettik…

Pandeminin bizi evlere kapattığı dönemde bir araya gelmenin farklı yollarına atıldık, forumlara ara vermedik.[26] Online forumlarla, pandemi öncesinde de var olan sinema ve okuma gruplarımızla dünyanın farklı yerlerinden farklı kadınlar ve kadınlık deneyimleriyle tanıştık, karşılaştık. Bu karşılaşmalar, evlere kapandığımız günlerde üstümüze gelen duvarlarda kâh delikler açmamıza, bazen de üstlerinden atlayıp geçmemize vesile oldu, çok iyi oldu. Çünkü her umutsuzluğa düştüğümüzde, yalnız hissettiğimizde dayanışmamıza, birbirimize, mücadele tarihimize döndük biz.

Bazen kendimizi, birbirimizi yorduk, küstük, küstürdük. Eleştirdik, eleştirildik. “Birbirimizle ilişkiler geliştirirken kurduğumuz dili, davranışlarımızı, kendimize ya da bu ilişkilere dönüp baktığımızda yaşadığımız sorunları, bu sorunları gidermek için neler yaptığımızı” konuştuk; “patriyarkanın sistemli olarak bizi karşı karşıya getirmeye çalışan politikalarına karşı farklılıklarımıza rağmen, Kadın Dayanışmasını güçlendirecek, birlikte güçlü olduğumuzu hissettirecek araçları,” feminist politikanın ilişkilenme biçimlerimizde bize açabileceği yolları aradık, taradık;[27] az gittik, uz gittik; kimi zaman yolun sonuna vardık, kimi zaman da girdiğimizden farklı bir yoldan çıktık.

Çıktığımız her yoldan başka bir hikayeyle çıkmış olduk belki. Ama arşınladığımız o yolları hem kişisel tarihimize hem de YKF tarihine not düştük. Feminist politikayı tartışmaktan da hiç vazgeçmedik.

Velhasıl geldik zaman yolculuğumuzun, şimdilik son ama başka yolculukların başlangıcı olan bir durağına. 2013 yılında yaşadığımız, tanık olduğumuz Gezi Direnişi ile feministlerin Gezi Parkı’nda kurduğu Mor Çadır'la başlayan yolculuğumuz, Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu;na evirildi ve bugün hâlâ devam ediyor. Afişe çıkmalar, protestolar, gece yürüyüşleri derken on yıldır çarşambalar bizim için Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu. Mor çadırla başlayan bu serüvende Gezi’den aldığımız mirasla ve belki de Gezi’nin mirası olarak da.

[1] http://www.sosyalistfeministkolektif.org/kampanyalar/istanbul-feminist-kolektif/gezi/yogurtcuforum/

[3] Yerel Yönetimlerden Ne Bekliyoruz?: https://www.facebook.com/events/560044534406434/ - Ocak 2019.

[4] Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu Yıldönümü Partisi, https://www.facebook.com/events/1640352412954981/ - Temmuz 2016; YKF'de Bu Hafta: Piknikli oyunlu forum, https://www.facebook.com/events/486682218777077/ - Ağustos 2019 vb. Yılbaşı partileri için örneğin Şaraplı Yılbaşı Sohbetleri, https://www.facebook.com/events/116673055375058/ - Aralık 2015; YKF 2023 Yılbaşı Partisi, https://www.facebook.com/events/1560046417800862/ - Aralık 2022; Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu - 2022 Yılbaşı Partisi, https://www.facebook.com/events/3217657301887817/ - Aralık 2021 vb.

[5] Ortadoğu : Darbe, Direniş, Kadın! 1.Hafta: Direnişler ve Kadın: https://www.facebook.com/events/1771051056475642/ - Temmuz 2016; Ortadoğu : Darbe, Direniş, Kadın! 2.Hafta: Darbeler ve Kadın: https://www.facebook.com/events/111625712614620/ - Ağustos 2016; Ortadoğu : Darbe, Direniş, Kadın! 3.Hafta: Türkiye'de Darbeler: https://www.facebook.com/events/595356690644325/ - Ağustos 2016.

[6] Güney Afrika’da toplumsal mücadele ve kadın hareketi: https://www.facebook.com/events/273601264214319/ - Ağustos 2021.

[7] Ortadoğu ve Kuzey Afrika'da Feminist Mücadele: https://www.facebook.com/events/4190292027672966/ - Ağustos 2021.

[8] Rote-Zora’yı konuşuyoruz: https://www.facebook.com/events/1055037488593563/ - Eylül 2021.

[9] 2022'de dünyadan kadın mücadeleleri: https://www.facebook.com/events/684091380084201/ - Ocak 2023.

[10] Örneğin YKF Geleneksel Takas Şenliği, https://www.facebook.com/events/530511287781566/ - Kasım 2019; YKF Takas Şenliği: Kışlıklar Dışarı!, https://www.facebook.com/events/379280845972710/ - Kasım 2018; Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu Takas Pazarı, https://www.facebook.com/events/279036142554325/ - Mayıs 2017. Mezatlar için Dayanışma Mezatımız, https://www.facebook.com/events/533629363685525/ - Şubat 2018 ve YKF Dayanışma Mezatı, https://www.facebook.com/events/467305027273702/ - Ocak 2020.

[11] İfşa/Teşhir Üzerine, https://www.facebook.com/events/1784814381778722/ - Aralık 2016.

[12] Atölyeler için örneğin; YKF'de Bu Hafta: Kokedema Atölyesi, https://www.facebook.com/events/993691738293119/ - Nisan 2023; YKF'de Bu Hafta: Ritim ve Beden Perküsyonu Atölyesi, https://www.facebook.com/events/1215842689305395/ - Kasım 2022; YKF’de Bu Hafta: Arzu ve Gökçe ile vegan mutfak atölyesi, https://www.facebook.com/events/577405410365508/ - Eylül 2021; Kart yazıyoruz, https://www.facebook.com/events/935710457331970/ - Aralık 2021; Şiddetsizlik Atölyesi https://www.facebook.com/events/972573439429489/ - Ekim 2015.

[13] YKF'de Bu Hafta: Psikolojiye Feminist Yaklaşımlar, https://www.facebook.com/events/464666037268119/ - Aralık 2017;

[14] Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu'nda bu hafta "AŞK" ı konuşuyoruz!, https://www.facebook.com/events/327290727778144/ - Şubat 2018; YKF’de Bu Hafta: 'Bilim kurgu sinemasında yapay zeka-insan aşkı, https://www.facebook.com/events/655882851547663/ - Temmuz 2019; YKF'de Bu Hafta: Aşk'ı Konuşuyoruz, https://www.facebook.com/events/1178136132537384/ - Mayıs 2020; Aşk mı hayatta kalma mücadelesi mi?, https://www.facebook.com/events/313364947346976/ - Aralık 2021.

[15] Örneğin YKF'de Bu Hafta: Queer Teorinin Düşünsel Kaynakları, https://www.facebook.com/events/2376364362609644/ - Şubat 2019; Lgbti+ Hareketin Türkiye Tarihi, https://www.facebook.com/events/2136128236700060/ - Şubat 2019; YKF'de Bu Hafta: Queer’den Ses, Söz, Göz, https://www.facebook.com/events/3123715517654644/ - Mart 2019; Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu Online'da bu hafta Asya Leman’la “Türkiye’de Queer ve Sanat”, https://www.facebook.com/events/231165681682126/ - Aralık 2020.

[16] Osmanlı'dan Erken Cumhuriyet'e Kadın Hareketi: https://www.facebook.com/events/1962082424068698/ - Temmuz 2017 ve 80'lerden İtibaren Türkiye'de Feminizm Tarihi: https://www.facebook.com/events/120745715229186/ - Ağustos, 2017.

[17] Bu Hafta: Eril Destanlara Karşı Kadınlar Kendi Tarihini Yazıyor, https://www.facebook.com/events/295034034280024/ - Mayıs 2017.

[18] “Elektrikli Modernleşme”:Kadın ve Gündelik Hayatın Dönüşen Ritmi, https://www.facebook.com/events/333166117101122/ ve 19.yy Osmanlı Hane İçi Çatışmalar,Kocalarını Zehirleyen Kadınlar, https://www.facebook.com/events/301768606932666/ - Haziran 2017.

[19] Paris Komününde Kadınlar: https://www.facebook.com/events/102488860407417/ - Temmuz, 2017.

[20] Osmanlı Son Döneminde Kadın İşçiler: https://www.facebook.com/events/570975766723397/ - Nisan, 2019; YKF'de Bu Hafta: Zapatista Kadınlarını Konuşuyoruz, https://www.facebook.com/events/392716008188745/ - Mart 2019.

[21] Yoğurtçu Kadın Forumu'nda Bu Hafta: Ben & Beden - Kadın, Toplum, Cinsellik Söyleşisi, https://www.facebook.com/events/1204207806256270/ - Haziran 2016; Hazzın erkek egemen kurgusuna karşı: bedenimizi tanıyor muyuz?, https://www.facebook.com/events/1383991801644871/ - Ocak 2017; YKF'de Bu Hafta: Seks Pozitif Bir Sunum, https://www.facebook.com/events/281053932406798/ - Ekim 2017.

[22] 1929-1933 Yılları Arasında Cumhuriyet'in Güzelleri: https://www.facebook.com/events/2203164199935673/ - Kasım 2018; Karma Örgütler, Meslek Odaları ve Sendikalarda Kadın Olmak: https://www.facebook.com/events/705505169631794/ - Nisan 2017.

[23] 4 Nisan 1913 - Kadınlar Dünyası’ndan alıntı, aktarılan etkinlik YKF'de Bu Hafta: Osmanlı'dan Erken Cumhuriyet'e Kadın Hareketi, https://www.facebook.com/events/1962082424068698/ - Temmuz 2017.

[24] YKF de Referandum Sürecini Kadınlar Açısından Değerlendiriyoruz, https://www.facebook.com/events/268074876937251/ - Nisan 2017.

[25] https://catlakzemin.com/yogurtcu-kadin-forumu-26-mayis-cuma-aksami-saat-2130da-tecavuze-karsi-eyleme-cagiriyor/; https://gazetekarinca.com/kadinlar-cinsel-saldiriya-karsi-sokakta-bagir-herkes-duysun-erkek-siddeti-son-bulsun; Kadına yönelik erkek şiddetine karşı mücadele: https://www.facebook.com/events/335309430580523/ - Kasım 2018.

[26] Nisan 2020’de YKF'de:Salgının Hayatlarımızda Yarattığı Değişimi Anlamlandırmak (https://www.facebook.com/events/223297835557584/) forumu ile başlayarak Ağustos 2021’deki YKF Bu Hafta Parkta - Miras'ı Devralmak (https://www.facebook.com/events/198166655615634/) forumuna kadar, yıldönümü pikniği hariç olmak üzere forumlarımızı online gerçekleştirdik. Akabinde parka çıkarak yüz yüze forumlara geri döndük, ara ara hibrit şekilde hem online hem yüz yüze forumlar gerçekleştirdik ancak sonrasında yalnızca yüz yüze forumlarla devam ettik. Aynı şekilde edebiyat, sinema ve okuma grubu gibi grupları da online toplantılarla sürdürdük.

[27] Birbirimizle İlişkilenme Biçimlerimiz: https://www.facebook.com/events/1106537112779327/ - Nisan 2017 ve Kadın Dayanışması Bizim İçin Ne İfade Ediyor: https://www.facebook.com/events/474220236405905/ - Ekim 2018.

Link to Catlak Zemin interview on Jadaliyya