In 2008, I visited the West Bank where I stayed with a host family in a village outside of Bethlehem. On my first day, I learned that they were Christians. I was twenty-two years old, and this was the first time I realized that Palestinians were not all Muslim. I felt horrified and embarrassed for traveling thousands of miles ignorant of this simple fact. That night, I heard intimate stories of “al-Nakba”—the catastrophe. I had never encountered such versions of events before, having only received this history told in a celebratory manner and recounted as the “Israeli War for Independence.” It was humbling to confront a radically different narrative, one of tribulation and loss.

My historical imagination felt very stunted in this moment. I recognized my own susceptibility to passively internalizing messages without critically interrogating the content. My sense of “knowledge” was limited to perceiving history as the study of the past rather than the limited and contingent attempt to find meaning in the past. I did not appreciate the power inherent in constructing a narrative, making it dominant, and imposing a name upon it. I failed to grasp the impact of elevating or marginalizing accounts and did not see the potential for counternarratives beyond the messages I had received. I accepted inherited wisdom and, in this moment, felt distraught over the disservice done to myself and other students who were denied a reckoning with perspectives outside of the singular and normative ones housed in the intimidatingly encyclopedic—yet somehow highly selective and incomplete—tomes found in classrooms.

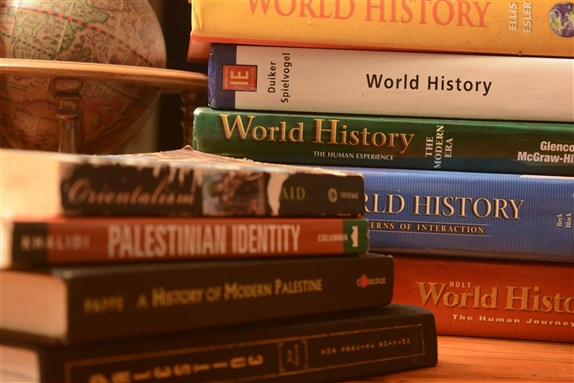

I left that experience in Bethlehem having concluded that perpetuating silences in classrooms was an inexcusable offense. I became committed to making classrooms more inclusive and less ethnocentric. Yet, in reviewing world history textbooks, it seems that mere inclusivity has its own faults if the content promotes rather than dispels stereotypes. Worse than not teaching is reinforcing notions of otherness that permeate representations which have long typified portrayals of the manifold inhabitants of the Middle East. For social studies teachers who broach the study of Palestinians in their classrooms, it is imperative to revisit and interrogate the presentation of Palestinians in some of the most widely circulating world history textbooks.

It begs the question: Who are Palestinians as depicted in the world history textbooks that students across the United States read and which may constitute a powerful influence on their thinking?

It is not merely a question of the way Palestinians are presented but, poignantly, of the definitions that are imposed or elided when shaping perceptions of an entire people.

Narratives interpret the past and shape perceptions in the present. History textbooks are potent vehicles for constructing a sense of social reality. They tend to present a singular vision of the past and, in the process, privilege certain accounts while displacing others from our shared collective consciousness. There is an implicit, yet often unrevealed, power negotiation in terms of which interpretations are elevated and which are neglected. Pointedly, this is a matter of whose assessment of the past becomes orthodoxy in our collective memory. So, it is not merely a question of the way Palestinians are presented but, poignantly, of the definitions that are imposed or elided when shaping perceptions of an entire people. These perceptions are not confined to textbooks and classrooms but transfer into political spaces. For Palestinians, there are tangible and deleterious implications for being assigned the role of the dangerous other.

While it is not novel to critique this epistemological stance central to the construct of history textbooks, it is urgent, however, that these ubiquitous tools for disseminating perceptions of the social world be critically “read against the grain.” This is necessary for understanding the narratives that vie for normativity in schools and the minds of students.

The portraits in five of the leading world history textbooks reinforce many of the reductive and demonizing depictions of Palestinians long seen in news media, television, and film. Yet, unlike the “reel bad Arabs” of cinema, they do not intentionally traffic in fiction. These textbooks purport to be authoritative and are written under the guise of objectivity. This positivistic stance obscures the embedded ideologies within purportedly neutral knowledge. It is highly consequential when a subjective interpretation is presented to students as definitive, particularly as they forge their social identities and are influenced to categorize between self and other.

Palestinian “Muslim Arab” Identity

World history textbooks tend to define Palestinians as “Muslim Arabs” in a problematic manner. For instance, Wadsworth Cengage’s World History establishes this working definition of Palestinian identity in the section “The Issue of Palestine” which focuses on the predicaments facing the British under the mandate system after the First World War. It states,

The land of Palestine—once the home of the Jews but now inhabited primarily by Muslim Arabs—became a separate mandate and immediately became a thorny problem for the British.

Later in this passage when discussing the impact of the Balfour Declaration, it begins to confuse and conflate the terms “Muslim” and “Arab” by reading,

But Arab nationalists were incensed. How could a national home for the Jewish people be established in a territory where the majority of the population was Muslim?

The terms “Muslim” and “Arab” appear in this and other textbooks interchangeably. This is underscored in statements such as,

As tensions between the new arrivals and existing Muslim residents began to escalate, the British tried to restrict Jewish immigration into the territory while Arab voices rejected the concept of a separate state.

Within the same sentence, the textbook alternates between the two terms, effectively conflating “Muslim” with “Arab.” It is true that the majority of Palestinians are Muslim and that the community is a subset within a broader Arab community. However, this language obscures any recognition that Palestinians are not interchangeable with other Muslim Arabs. The particularities of Palestinian national self-identification are lost when the community becomes subsumed into broader classifications that extend far beyond itself.

The emphasis on being Arab without any distinctiveness has the effect of absorbing Palestinians into a much more expansive community stretching from the Atlantic in Morocco to the Arab states of the Gulf. While Palestinians are considered members of an Arab nation, this should not be used to minimize a Palestinian imagining of themselves as a national community with its own identity and search for sovereignty. In Palestinian Identity: The Construction of a Modern National Consciousness, Rashid Khalidi recognizes the difficulties Palestinians have historically faced when Ottoman, Arab, Muslim, and other designations preclude recognition of their sense of nationhood. These textbooks reinforce Khalidi’s observation that Palestinian national identity suffers from a tendency to be undermined by its overlap with other ethnic, religious, and regional categorizations.

It is often asked why Palestinians merit a state when there are twenty-two Arab states. This question presumes all Arabs are interchangeable and lack an affirmative sense of communal self beyond Muslim and Arab collective ties. Palestinians are not all Muslim and have experienced a historical trajectory that is in many ways distinctive from Arab counterparts elsewhere. The consequences are not innocuous when textbooks minimize this distinctiveness. Its impact is to implicitly delegitimize Palestinian claims to sovereignty.

This framing of Palestinians as “Muslim Arabs” also has the added impact of laying the narrative foundation of an apparent religious conflict between Jews and Muslims rather than a political conflict between two contending nations seeking sovereignty over the same territory. This narrative could be problematized if textbooks mentioned the sizable Christian Palestinian community. Yet, intra-Palestinian diversity is neglected. An account of an intractable religious confrontation does not so easily hold up when the religious heterogeneity of Palestinians is acknowledged. Textbooks tend to enable the conclusion that the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is primarily a matter of religious antagonism between Jews and Muslims at the expense of layering the lenses of nationalism and anti-colonialism which would, effectively, confound such a reductive conclusion.

Palestinians as Terrorists

World history textbooks confine Palestinians to accounts of conflict, thereby omitting any sense of their lived experiences, culture, and collective identity beyond the scope of an unresolved geopolitical dispute. Emphasizing the conflict with Israel is undeniably important. Without addressing it, textbooks would be sanitized and students denied access to studying a prolonged and contested issue that has garnered the world’s attention. By introducing the conflict, textbooks also have the potential to explore the manifold forms of Palestinian experience during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Yet, the diversity of experience—as refugees in diaspora, citizens of Israel, under occupation, etc.—are not discussed at length or at all in world history textbooks.

In The Forgotten Palestinians: A History of the Palestinians in Israel, Ilan Pappe reminds readers of the intra-Palestinian diversity and fragmentation brought on by the conflict that is often overlooked in the discourse of Israel and Palestine. The erection of boundaries and the consequences of displacement have launched segments of Palestinians on different historical trajectories. However, there is minimal recognition of these experiences within world history textbooks. At most, they offer cursory mention of refugee camps because the emphasis in categorizing Palestinians lays elsewhere. Instead, Palestinians are positioned as aggressors and consistently relegated to this category. This means that Palestinians are rarely presented in any capacity outside of being historical actors responsible for meting out violence.

Assigning this role to Palestinians relies on establishing a lexicon. Establishing Palestinians as “terrorists” and “guerillas” is central to this vocabulary. World History: Patterns of Interaction, is replete with such mentions. For instance, when introducing the Palestine Liberation Organization, it explains,

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s the group carried out numerous terrorist attacks against Israel. Some of Israel’s Arab neighbors supported the PLO’s goals by allowing PLO guerillas to operate from their lands.

This designation was recurrent across passages, being used in reference to the second intifada.

In response to the uprising, Israeli forces moved into Palestinian refugee camps and clamped down on terrorists.

This passage reveals the way refugee status, while briefly mentioned, is minimized to emphasize how camps exist as “terrorist” havens.

Prentice Hall’s World History also consistently relies on this binary of “guerilla and terrorist.”

After the 1948 war that followed Israel’s founding, Israel and its Arab neighbors fought three more wars, in 1956, 1967, and 1973. In these wars, Israel defeated Arab forces and gained more land. Between the wars, Israel faced guerilla and terrorist attacks.

Wadsworth Cengage’s World History attributes the stalled peace process to Palestinian “militants.” A description of the failure to ascertain peace after the Oslo Accords states,

Progress in implementing the agreement, however, was slow. Terrorist attacks by Palestinian militants resulted in heavy causalities and shook the confidence of many Jewish citizens that their security needs could be protected under the agreement.

Textbook attributions of the persistence of conflict rest responsibility primarily on Palestinians. This argument is made possible by the designation of “terrorist” or “militant” which imbues Palestinians with malevolence and circumscribes the reader’s understanding of the population to that of a bellicose and violent community. Moreover, World History: The Human Journey grants readers added specificity regarding violent tactics and, in doing so, employs the designation “Palestinian suicide bombers” in a description of the Road Map when stating,

Although both sides have pledged to follow the plan, each continues to blame the other for a lack of progress. In the meantime, Palestinian suicide bombers continue to blow themselves up in Israel in an effort to kill Israelis.

The violence of the second intifada originating from Palestinians is frequently invoked. For instance, World History: Patterns of Interaction explains,

The second intifada began much like the first with demonstrations, attacks on Israeli soldiers, and rock throwing by unarmed teenagers. By this time the Palestinian militant groups increasingly used suicide bombers. Their attacks on Jewish settlements in occupied territories and on civilian locations throughout Israel significantly raised the level of bloodshed.

Each of these terms—terrorist, guerilla, militant, suicide bomber—appears in these texts self-evidently. They are not in dispute or seen as subjective. There is a bluntness to this terminology compounded by the absence of commentary regarding the decision to introduce this schema to young readers.

Recognizing the problematic manner in which world history textbooks categorize Palestinians is not a matter of condoning violence or apologizing for it. Instead, it is about discerning the fashion in which Palestinians are consistently equated with language that is steeped in negative associations. There is no transparency offered in the decision to select these terms, emphasize these acts, and elide other possible frameworks for understanding the roles Palestinians have played historically and today. Instead, the texts assume the posture of presenting irrefutable truth.

Textbooks do not need to ignore violence perpetrated among Israelis and Palestinians. It is a feature of this conflict that has caused anguish among both populations. However, consistently framing Palestinians as aggressors defined entirely by their opposition decontextualizes violence more than it provokes understanding of the conflict. It also eclipses the behavior of Israel in the saga of aggression and militant behavior. It presents Palestinians in absolute terms where their singular defining trait is as perpetrators of violence. The consequence of this is to render Palestinians unintelligible to the reader. They seem essentially menacing, illogical, and uniquely prone towards militancy.

World history textbooks present Palestinians as alien in their motives and deeds. There is little emotional association that can be made with Palestinians when they are vilified rather than understood on their terms and as complex social actors. They become totally different and unrelatable. Palestinians appear as the embodiment of alterity, fundamentally dissimilar and antithetical in their identity and conduct. These terms—terrorist and militant—accomplish more than describe behavior. They establish a sense of remoteness that renders Palestinians entirely other and devoid of redeeming or familiar characteristics.

Palestinians Defined by Emotion

Emotions are undeniably fundamental to human experience. The episodes recounted in world history textbooks are replete with the potential for emphasizing the emotional range of historical actors. Yet, the emotional state of individuals and communities is not central to the expansive topics found in these textbooks. The mention of Palestinians, however, is laden with references to the supposed emotional state of the community. Palestinians’ apparent emotional range is also quite circumscribed as they appear captive to anger and rage.

For instance, World History: The Human Journey centers emotions when stating,

The establishment of a Jewish nation infuriated Palestinian Arabs. As soon as British troops withdrew from the area, armies from neighboring Arab countries moved against Israel. Although outnumbered, the determined Israelis won.

Ascribing emotions to an entire population cast millions of people as a rigid and monolithic entity lacking depth or complexity. Moreover, world history textbooks present Palestinians as driven by emotion rather than rationality, complementing their assigned role of terrorists.

Palestinians appear devoid of legitimate grounds for feeling and behaving. Instead of logical, thoughtful, strategic, or deliberate, they are driven by angry opposition. Again, world history textbooks reflect a tendency to sidestep any effort to understand or empathize with Palestinians. Additionally, they abstain from offering a robust sense of Palestinian national aspirations and why their sense of being stymied may evoke such emotional responses.

Palestinian Destructive Agency

A persistent problem in many textbooks that have been critiqued for ethnocentric orientations is the tendency to relegate certain communities to the backdrop of narratives. Christine Rogers Stanton has identified the practice of usurping the agency of Native Americans in United States history textbooks. They are passive, acted upon, and are not central to the forward motion of history. Rather than being historical agents, they are objects on the landscape of the past. As real as this problem may be for certain subaltern communities, it is not the most salient problem in the portrayal of Palestinian agency. World history textbooks present Palestinians as agents. They appear to act, destructively.

Consistent with the presentation of “infuriated” “terrorists” is the tendency to assign destructive tendencies to Palestinians. World History: The Human Experience shows Palestinians acting in “armed struggle” during “terrorist attacks” and “border raids.” One passage reads,

The United Nations asked Israel to pull out of occupied territories and asked Arab nations to recognize Israel’s right to exist. Both sides refused. Terrorist attacks and border raids continued for many years.

Similarly, Prentice Hall’s World History tells readers that under the British Mandate,

[A]s more Jews moved to Palestine, tensions between the two groups developed. Jewish organization tried to purchase as much land as they could, while Arabs sought to slow down or stop Jewish immigration. Arabs attacked Jewish settlements, hoping to discourage settlers.

Later, in the context of describing the PLO it continues,

For decades, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) led the struggle against Israel. Headed by Yasir Arafat, the PLO had deep support among Palestinians. The PLO called for the destruction of Israel. It attacked Israelis at home and abroad.

These passages are not as explicit as World History: The Human Journey when it states, “Palestinian suicide bombers continue to blow themselves up in Israel in an effort to kill Israelis.”

These statements continue to epitomize the tendency to obscure any recognition of Palestinian voices or perspectives within the master narrative housed within textbooks. Additionally, they are devoid of alternative frameworks for understanding. For instance, they do not present an anticolonial account. There is no significant discussion of liberation struggle. These textbooks narrowly confine the window into Palestinian action so that destruction becomes an inescapable condition of Palestinian agency and the only one worth mentioning. There appears to be no other noteworthy Palestinian mode of conduct deserving recognition. The overall impression left by these narratives is that there is a community of infuriated Muslim Arabs actively seeking destruction. No Palestinian position is affirmed within such a dominant interpretation.

What is the young reader of these textbooks led to think about Palestinians?

Students in US classrooms who encounter this paradigm are denied an intellectual encounter with diversity. No semblance of Palestinian plurality is recognized. A population that is more than one singular entity becomes uniform through these accounts. Struggles within refugee camps, in diaspora, and in advocating on the world stage for their national movement are conspicuously absent from these accounts. Moreover, the uniformity of these presentations ensures that Palestinians appear vastly different than the textbook’s readers. Palestinians appear prone to terrorism and violence; they are framed to be diametrically unlike communities meriting empathy and understanding.

Disseminating this knowledge to students is not a benign act because historical study in schools is not a socially innocuous process. The lessons taught in this context are formative in establishing young people’s scope and sense of their social reality. Without multiple narratives to entertain, students are given the message that the study of the past is coherent and that these versions are unimpeachable. This is not the case. Historical narratives are efforts to impose meaning. They are contested space. The selection of one narrative over another is an act of power to define, silence, and shape collective understanding. Without honoring this in classrooms, textbooks circumscribe students’ understanding in ways that are untenable in their lives, particularly as individuals capable of weighing contending perspectives, critically deconstructing information, and making informed decisions. Students leave the classroom encumbered by a false sense of the nature of historical knowledge. In this instance, it reverberates to limit their vision of Palestinians.

Seeing Palestinians through the Orientalist Gaze

These world history textbooks view Palestinians through an Orientalist gaze. Palestinians are essentialized and known only as aggressors in conflict. Without their voice or any effort to understand this history from their vantage point, external views of their actions and historical experiences become definitive. These textbooks reveal no interest in representing Palestinians in any other terms or context. Conflict, violence, disorder, and instability become the sole reference points for students to access Palestinians via these learning tools. Culture, community, and identity are remote from what these textbooks consider to be worthy of young people’s attention.

If textbooks included a narrative that presented al-Nakba, the categories used to describe Palestinians would have to be reconsidered and transformed. Textbooks would have to honor suffering, economic insecurity, political fragility, and the coping mechanisms that generations have employed for decades. Yet, al-Nakba is not featured in these renditions. In turn, Palestinian humanity is very much absent. It is hard to humanize people when they become shorthand for terrorists. When complexity dissipates, Palestinians are fitted into a longstanding tradition of exotic Orientals vastly unlike the reader encountering them on the page.

All this matters in an age when the United States is systematically rolling back economic and humanitarian assistance to Palestinians. Headlines of the Trump Administration moving the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem or withholding millions of dollars in aid to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East may constitute young American students’ first or most recent points of contact with general news and information about Palestinians. When textbooks “demystify” this population in the manner that they do, the policies of the Trump Administration may seem ethical and, even, necessary. The logic of these policies is reinforced by the negative connotations textbooks construct in their depictions.

Palestinians have their voice, identity, and interests usurped when these textbook renditions serve as authoritative accounts of who they are and how they behave. A disservice is done to students when they are not presented with learning materials tailored to helping them think critically, autonomously, and complexly. There is a need to introduce counternarratives of Palestinians’ experiences in classrooms while instilling the capacity for students’ ability to unpack these texts and better understand the nature of historical knowledge construction. This approach in schools will go a long way toward dismantling the hegemony of an Orientalist gaze and affording students with the opportunity to entertain multiple perspectives that reveal nuance and humanity.