[Engaging Books is a monthly series featuring new and forthcoming books in Middle East Studies from publishers around the globe. Each installment highlights a trending topic in the MENA publishing world and includes excerpts from the selected volumes.This installment involves a selection from Hoopoe on new fiction from the Middle East. Other publishers' books will follow on a monthly basis.]

Table of Contents

By Omaima Al-Khamis; translated by Sarah Enany

About the Book

About the Author/Translator

In the Media/Scholarly Praise

Additional Information

Where to Purchase

Excerpt

Call for Reviews

The Critical Case of a Man Called K

By Aziz Mohammed, translated by Humphrey Davis

About the Book

About the Author/Translator

In the Media/Scholarly Praise

Additional Information

Where to Purchase

Excerpt

Call for Reviews

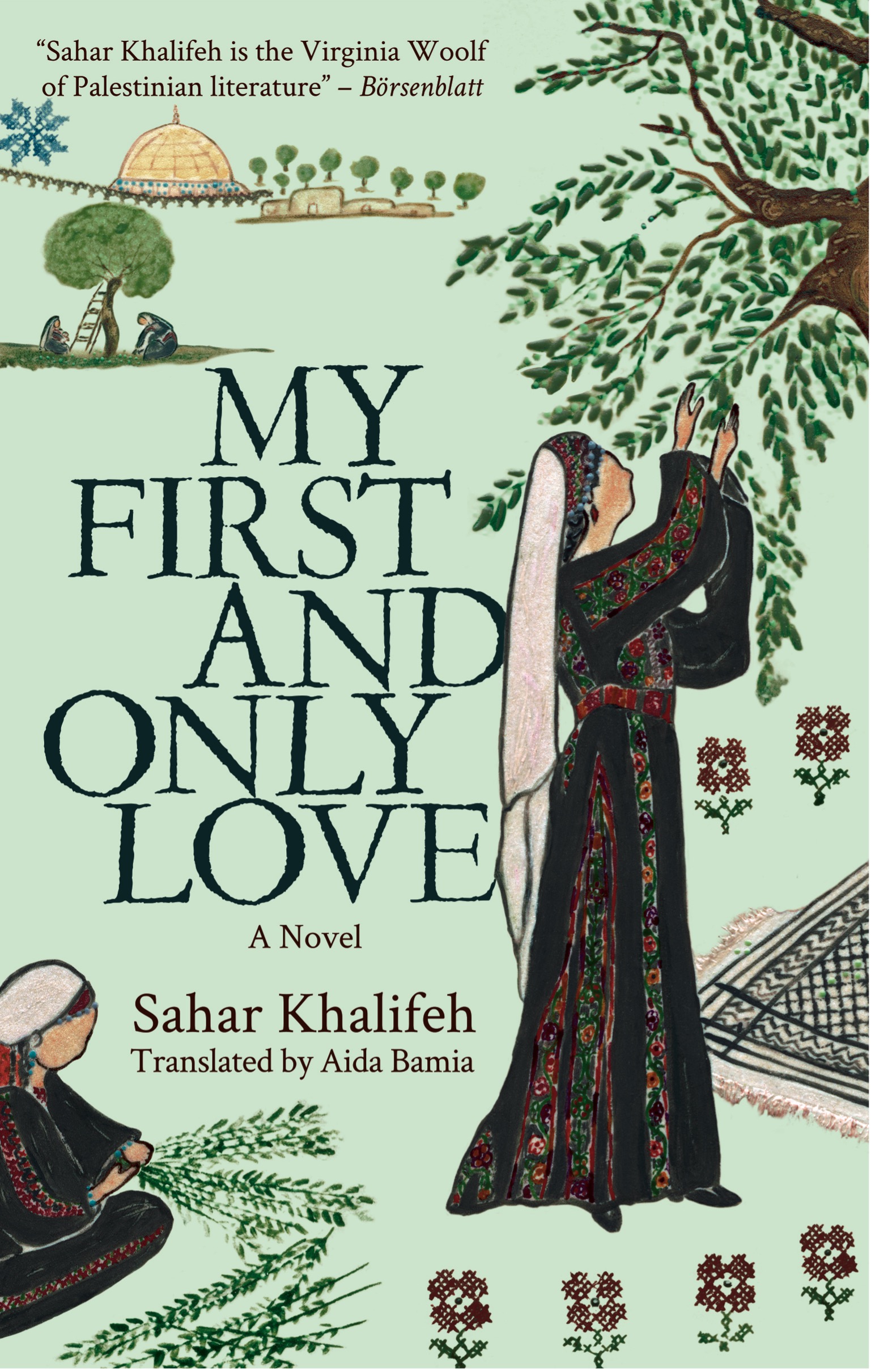

By Sahar Khalifeh, translated by Aida Bamia

About the Book

About the Author/Translator

In the Media/Scholarly Praise

Additional Information

Where to Purchase

Excerpt

Call for Reviews

By Omaima Al-Khamis; translated by Sarah Enany

About the Book

A magical story of a Crusade-era bookseller who embarks on a journey through the Islamic world’s great medieval cities, winner of the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature

In the epic fashion of the great Arab explorers and travel writers of the Middle Ages, scribe and bookworm Mazid al-Hanafi narrates this journey from his remote village in the Arabian Desert. Dreaming of grand libraries, his passion for the written word draws him into a secret society of book smugglers and into the famed cultural capitals of the period—Baghdad, Jerusalem, Cairo, Granada, and Cordoba.

He discovers a dangerous new world of ideas and experiences the cultural diversity of the Islamic Golden Age, its sects, philosophical schools, wars, and ways of life.

Omaima Al-Khamis’s magical storytelling and her vivid descriptions of time and place trace a route through ancient cities and cultures and immerse us in a distant era, uncovering the intellectual debates and struggles which continue to rage today.

About the Author and Translator

Omaima Al-Khamis was born in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia in 1966. A prolific writer, columnist, critic, social reformer, and women's rights activist, she has published novels, short-story collections, opinion pieces, and children's books. The Book Smuggler, her fourth novel, won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature, and was longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, both under the title, Masra al-gharaniq fi mudun al-aqiq (Voyage of the Cranes over the Agate Cities.) It is her English language publishing debut. She lives in Riyadh with her husband, two sons, and daughter.

Sarah Enany is a literary translator and a professor in the English Department of Cairo University.

In the Media/Scholarly Praise for The Book Smuggler

Winner of the Mahfouz Medal for Literature

Longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction

“Al-Khamis draws upon medieval Arabic travel literature (adab al-rihla) and a great humanist tradition spanning East and West. Her language exquisitely traces a route through beleaguered cities in a novel that speaks to the importance of culture, imbuing them instead with rare and precious knowledge.” —Tahia Abdel-Nasser, associate professor of English and Comparative Literature, The American University in Cairo

"The hero’s epic journey takes the reader not only through the lands of the eleventh-century Arab oikumene that stretched from Baghdad to Andalusia, but simultaneously across a world of intellectual debate and struggle in which may be found the roots of many of the issues, and turmoil even, of the region today. For the Western reader, this novel will bring to mind much that is familiar in his or her own history.” —Humphrey Davies, Judges Committee for the Naguib Mahfouz Medal

Additional Information

April 2021

560 pages

$18.95 (list price)

ISBN: 9781617979989

Where to Purchase

US: Bookshop https://bookshop.org/books/the-book-smuggler/9781617979989

UK: Bookshop https://uk.bookshop.org/books/the-book-smuggler/9781617979989

Excerpt

Chapter Four

I walked slowly through the markets and alleyways: the paved pathways and stone walls were not unlike the city of Bosra, but these were wider and the air was purer. In the squares and culs-de-sac were orange trees bearing early blossoms, for it was still chilly around us. The folk of Jerusalem were mostly Arab and Surianese, though there were others whose provenance I could not make out; at any rate, they did not resemble the folk of Baghdad. Their faces were ruddy, their features finer and more delicate, and their movements more graceful and smoother. No one paid any attention to me. The city was packed with pilgrims, and it appeared that they were accustomed to seeing strangers here; or perhaps it was my mean and poor appearance after a month on the back of Shubra that made their eyes look through me. Even the store owners did not cry their wares when I passed; they turned away from me carelessly. “I must do something about my appearance,” I thought.

I went to a barber and asked him to cut off my two long braids. It was no easy decision: I felt shorn, as though I were cutting off Shammaa’s braids. My mother always took care of my hair, perfumed it with nutmeg, and braided it with powdered cloves. All the people of al-Yamama wear their hair in braids. In Baghdad, I wore them rolled up under my turban to avoid mockery. After the barber cut them off, I took my braids, dug a hole in a corner of the city, and buried them in the same place as the graves of the prophets, muttering wryly, “Perhaps my braids will help me on Judgment Day; they say that those buried in Jerusalem will never be damned.”

I had my beard and mustache trimmed, relieving them of the repulsive unkempt look they had acquired, keeping only enough for a manly appearance without looking like a wild man or a Bedouin. From the roofed-in marketplace, I bought a new shirt and pantaloons, and went into a bathhouse in the market whose steam seemed to penetrate to the bottom of my lungs. It was built upon a spring that gushed hot water without ceasing.

When I finished, I put on a few drops of the Byzantine rose perfume that the owner of the caravan had given me: thus I was ready to meet Amr al-Qaysi as a well-groomed bookseller from Baghdad, not an unkempt desert Arab who had leapt out from behind some sand dune and landed in Jerusalem. After I emerged from the bathhouse and donned my new clothes, my movements suddenly became more graceful and my voice lower. My steps grew slower and smoother, and when I sat, I did so with some fastidiousness, so as to avoid the places that might tear or stain my new clothes.

* * *

I went to the Great Mosque of Umar for the afternoon prayers, in search of the discussion circle of Amr al-Qaysi. I approached the attendant, or perhaps it was the muezzin—I could not tell, for he wore a bright white turban and a green caftan. I greeted him carefully and asked, “Are you from this city?”

He answered me readily, courteously, with no trace of wariness, “From the moment I opened my eyes. We trace our ancestry to the Arabian tribe of Kalb, which came and settled in the Levant, its origins being from the Peninsula.” He added, familiarly and a little proudly, “We are the uncles of Yazid ibn Muawiya, on the mother’s side. His mother is Maysoon, daughter of Bahdal, from the clan of Kalb.”

The minarets of Jerusalem pray the Shiite prayer for the Prophet’s descendants, while this muezzin prides himself on being related to the enemy of Ali ibn Abu Taleb, Yazid ibn Muawiya. I sensed that his world was limited to the confines of this mosque. At that time, I was not yet accustomed to the nature of the Levantines, who were open and friendly with foreigners and expansive with strangers. I had learned from my stay in Baghdad that a stranger had strict limits, beyond which one was expected to hold one’s tongue, for you never knew what you might say that would result in a dagger being brandished in your face.

He adjusted his turban, then raised his white eyebrows and said as though just remembering, “Where are you from?”

I said shortly, “I am a Hanafite Sunni from al-Yamama.” I paused to see the effect of the name on his expression. Would he recite the black list that they always teased me with: kin to Musaylima, horn of the Devil, and so on?

But his face showed no indication of having ever heard of it. He only said, “Oh, you have journeyed a long way. Are you a student or a merchant?”

“Both,” I responded.

His simple demeanor and clear responses allowed me to look my fill at the beautiful colored ornamentation in the colonnade and its pillars and arches. He kept talking, not realizing my distraction. After some hesitation, I asked, “Do you know Amr al-Qaysi? I was told that he holds his discussion circle here.”

His smile made three deep vertical lines in his cheeks. “Why, whom should we know but Sheikh Amr al-Qaysi, God bless him? He is our sheikh and speaker and the preserver of our knowledge, a good man and devout, full of inexhaustible wisdom.” I had clearly sparked his interest with my question about the sheikh: he appeared to have a great deal to say. “Tell me about the way you took, and the caravan you went with.”

“I am a bookseller,” I said shortly. “They told me that Jerusalem is thirsty for books.”

He puffed up with the air of one with pretensions to knowledge. “Who does not love books? Show us what you have, Arab of the desert. Are there any true God-fearing men who are not men of knowledge? We Jerusalem folk are fond of learning, and students always come to us: they all say, in praise of the city, ‘I would fain be a straw in one of the mud bricks of Jerusalem.’”

His expansiveness did not sit well with my wary and cautious nature. Quietly, I said, “God willing, I shall bring some of them here.” I added hurriedly, “But where can I find Amr al-Qaysi?”

He pointed at the gravelly floor where he stood. “Here,” he said. I stared at him, astonished. He went on, “He has held a discussion circle here after the afternoon prayers daily since he arrived in Jerusalem.” Before I could ask, he went on: “But I could not tell you where he lives, as he prefers not to receive visitors in his house.”

I guessed deep within me that he had said this so as to watch my meeting with Amr al-Qaysi and find out what I sought. He added, “Everything in the pot comes out with the ladle. Just wait until the afternoon prayers.”

Call for Reviews

If you would like to review the book for the Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya, please email info@jadaliyya.com

The Critical Case of a Man Called K

By Aziz Mohammed, translated by Humphrey Davis

About the Book

A sensitive and at times darkly humorous story of a young man's experience of illness, his contemplation of death, and his determination to maintain his independence through it all

After reading Kafka, K decides to write his own diary, but he is constantly frustrated by his lack of experiences: he is worn down by the drudgery of his corporate job for a faceless corporation and by his incessant family obligations.

When he receives the news that he has leukemia, he finds himself torn between a sense of devastation and a revelation that he has finally found a way out of his writing predicament. Through Mohammed's measured but forceful writing, this compelling debut has a universality that reaches across time, place, and culture.

About the Author and Translator

Aziz Mohammed is a Saudi literary author, born in Khobar City in 1987. His debut novel The Critical Case of a Man Called K was published in 2017 and was shortlisted in 2018 for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, known as the "Arabic Booker." He was the youngest and the first debut author to be shortlisted in the history of this prestigious prize. He has since participated in cultural programs of literary festivals, book fairs, and cultural centers all around the Middle East as a literary author and cinema critic.

Humphrey Davies is an award-winning literary translator of Arabic into English. He received first class honors in Arabic at Cambridge University and holds a doctorate in Near East Studies from the University of California at Berkeley. He has won and been shortlisted for numerous literary prizes and has twice been awarded the prestigious Saif Ghobash-Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation. He has translated Naguib Mahfouz, Elias Khoury, Mourid Barghouti, Alaa Al-Aswany, and Bahaa Taher, among others. He lives in Cairo, Egypt.

In the Media/Scholarly Praise for The Critical Case of a Man Called K

Shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction

"In his first novel, the author managed to create a unique balance between his observations of the community and himself; between sweetness and pain; sadness and irony; the depth of experience and the flow of the narrative. This is a novel that touches the soul."--Muhammad Abdelnabi, ArabLit

"This engaging novel is written in a diary format, with the protagonist recording his daily battles with life in a sarcastic voice. The narrative flows smoothly . . . his story [is] interesting and touching."--Ruba Obaid, Arab News

"Compelling . . . well-timed, humorous observations . . . [the narrator's] story progresses toward deeper understanding of the human condition."--Foreword Reviews

Additional Information

April 2021

266 pages

$17.95 (list price)

ISBN: 9781649030757

Where to Purchase

US: Bookshop https://bookshop.org/books/the-critical-case-of-a-man-called-k/9781649030757

UK: Bookshop https://uk.bookshop.org/books/the-critical-case-of-a-man-called-k/9781649030757

Excerpt

Chapter One

The moment I wake, I’m overcome by a feeling of nausea.

I take a breath with difficulty, rub my eyes, stare out through a pall of sleep. There are dark spots on the pillow. I deduce from the way I’m breathing that they must have come from my nose. The left side of my mustache is stiff with coagulated blood and the blood in my nostrils is still moist. I jerk into consciousness, raise my head, and, in an instant, my pulse returns to normal. From the position of the sun in the window, I realize that I am, however you look at it, late. I turn over onto the other half of the pillow and close my eyes again.

I remember that before I went to sleep, just before dawn, I was reading a book and before that I’d taken a hot shower, which I’d read somewhere makes you sleepy. Before that, I’d had dinner, smoked, moved around from room to room, turned the lights on and off, got into bed and got out again, stood up and sat down, all to no purpose. Nothing different from what people do every night if they can’t sleep. I’ve chosen a bad day to make do with just two hours’ sleep, though any other day would be just as bad. From the midst of the chaos of the bedside table, the alarm clock’s harsh bell keeps hammering away, like a nail being driven into my head.

It takes a few minutes for me finally to get out of bed. I turn over in my mind the fact that I’m late, without this impelling me to hurry. I piss, and from the color deduce that I’m dehydrated. I clean my teeth till the gums hurt, from which I deduce that I’ve cleaned them long enough. I wash the traces of sleep off my face and of blood off my mustache and the inside of my nostrils. I smell the familiar metallic smell. A little blood trickles down my throat, like a burning clot of old memories.

As a child, I was always getting nosebleeds and would become aware of the movement of the warm blood as it trickled down through the respiratory tract before I saw it fall onto my clothes and feet. The first moment of seeing it was always terrifying, even though there wasn’t any pain. Nosebleeds often prevented me from joining in games with the other boys after school, especially on hot, sunny days, and even though I became an expert at stopping the bleeding (by, for example, holding an ice cube against the top of my nose or closing the open vein by pinching it with two fingers from the outside), the sun, in its fury at this land, could always make it flow again.

Now, though, it’s winter. I check by looking through the window. The day is bright, the sun’s rays falling on traces of recent rain. I dress in a hurry, my only concession to being late. As soon as I leave the house, the downpour resumes.

In the car, music blasts out the moment I turn the key. I silence the radio with the same violent movement that I used to reach out to the alarm clock on the dressing table. Not a thought enters my head throughout the journey. The front windshield wipers move right and left like a hypnotist’s pendulum. Suddenly, I find myself at the overflowing parking lot and become aware again of where I am. I park far away and walk with hurried steps. It’s cold and something urges speed.

A number of times, during the long walk toward it, I raise my head to look at the tower. The entire building is visible and it’s easy to find your way to it from anywhere, but the entrance remains hidden and getting to it requires several twists and turns. The closer you get, the more you feel you will never enter.

Everything is the way it was yesterday, but the feeling of alienation the building inspires is so strong that somehow it all seems different.

Immediately after you cross the side entrance, a strong smell of paint erupts, which the unventilated corridor holds in place. At the end of the corridor there’s an escalator, whose end is invisible from where it starts and which moves endlessly upward, as though it could take you to wherever you want to go, though in fact it takes you only to the elevator lobby, where you wait. This late in the morning, no one is waiting in the lobby but me. Empty or full, however, makes no difference to how long you have to wait.

The lobby’s glass façade looks out over an exterior courtyard containing a garden, in which no one ever strolls, and wooden benches, used by smokers. I can always tell how late I am by the number of smokers outside: no one goes out for a smoke immediately after he arrives; he has first to have been noticed by those upstairs long enough to establish his presence. Who knows? Perhaps the glass façade was made specifically so that people could fill their vision with such observations while waiting, and the moment the elevator arrives, rush into it, as though unable to bear the sight a moment longer.

I enter and press the button for the tenth floor. The door remains open for a while before closing automatically. I glance at my watch. I check the zipper of my pants, as I often forget about it. I contemplate my clothes from top to bottom, as though noticing for the first time what I’m wearing.

The second I reach the tenth floor, I hide my hands in my pockets and try to look like someone confident he’s on time. I maintain this look as I cross the marble corridor to the administrative offices and open the glass door that keeps the department separate, then make my way along the narrow aisles between the rows of desks, taking care to avoid bumping into this person or returning that one’s greeting, and finally sit down in front of the computer. I pull off the yellow sticker, knowing without reading it who wrote it and stuck it on the screen, then say good morning to the Old Man, who sits next to me, my voice sounding scandalously exhausted. A phrase from Kafka’s Diaries, which I’m reading these days, keeps repeating itself in my mind: “At this sudden utterance some saliva flew from my mouth as an evil omen.” When I hear the wan voice next to me return my greeting, I realize, as though discovering this for the first time since I woke, that it’s just another ordinary day at work.

Call for Reviews

If you would like to review the book for the Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya, please email info@jadaliyya.com

By Sahar Khalifeh, translated by Aida Bamia

About the Book

A deeply poetic account of love and resistance through a young girl's eyes by acclaimed writer, Sahar Khalifeh, called "the Virginia Woolf of Palestinian literature" (Börsenblatt)

Nidal, after many decades of restless exile, returns to her family home in Nablus, where she had lived with her grandmother before the 1948 Nakba that scattered her family across the globe. She was a young girl when the popular resistance began and, through the bloodshed and bitter struggle, Nidal fell in love with freedom fighter Rabie. He was her first and only real love--him and all that he represented: Palestine in its youth, the resistance fighters in the hills, the nation as embodied in her family home and in the land.

Many years later, Nidal and Rabie meet, and he encourages her to read her uncle Amin's memoirs. She immerses herself in the details of her family and national past and discovers the secret history of her absent mother.

Filled with emotional urgency and political immediacy, Sahar Khalifeh spins an epic tale reaching from the final days of the British Mandate to today with clear-eyed realism and great imagination.

About the Author and Translator

Sahar Khalifeh, born in Nablus in 1941, is an acclaimed Palestinian author. She is hailed as a feminist writer and has written eleven novels, which have been translated into English, French, German, Spanish, and many other languages. She has won numerous international prizes, including the Naguib Mahfouz for Literature for The Image, the Icon, and the Covenant. As a young woman, she was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study in the United States and holds a Masters in English Literature from the University of North Carolina and a PhD in Women's Studies and American Literature from Iowa University. She currently lives in Amman, Jordan.

Aida Bamia is a literary translator and professor emeritus of Arabic language and literature at the University of Florida in Gainesville, where she lives.

In the Media/Scholarly Praise for My First and Only Love

"The best Arab woman novelist in the twentieth century."--Dr. Bouthaina Shaaban

"Khalifeh is simply the greatest Palestinian novelist and one of the world's greatest historical novelists, ranking with Naguib Mahfouz, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, and Pramoedya Ananta Toer."--James Holstun, Professor of English, University at Buffalo

"Khalifeh effectively paints a crazy world where individuals seek to lead normal lives under nightmarish conditions . . . .Highly recommended." --Library Journal

"In Khalifeh's book, Palestinian Christians and Muslims, Jewish immigrants, and British colonial leaders are all treated with equal sympathy"-- Women's Review of Books

"Incisively explores individual lives--particularly women's lives--in the years just before 1948."--Marcia Lynx Qualey, Arabic Literature

"The author invokes a sacred heritage that remains at once vital and powerful."--Dr. Abdel Moneim Tallima

"Sahar Khalifeh is the Virginia Woolf of Palestinian literature."—Börsenblatt

ArabLit interview with tranaslator, Aida Bamia: Aida Bamia on Why ‘My First and Only Love’ Was Such An Emotional Translation Experience

Additional Information

April 2021

400 pages

$19.95 (list price)

ISBN: 9789774169830

Where to Purchase

US: Bookshop https://bookshop.org/books/my-first-and-only-love/9789774169830

UK: Bookshop https://uk.bookshop.org/books/my-first-and-only-love/9789774169830

Excerpt

Chapter Four

We entered the village with the call for the noon prayer and saw the men walking in the direction of a small mosque in the center of the village, which was nothing more than a narrow asphalt street—or rather, it had the semblance of asphalt, with holes, gullies, dirt, straw, and sheep droppings everywhere. It was surrounded by kharafish al-rabie and mulukhiyeh plants. Modest shops lined the street on both sides. They were facing the backyards of mud houses, hidden behind peach, fig, and apricot trees, with the fields of lentil, fava beans, and tomatoes beyond them.

Our presence attracted the attention of some of the young men, but the older men lowered their gaze. The children, who were standing by the shops and the displayed merchandise, looked at us as if we had landed from Mars. With my dress, braids held with ribbons, shiny shoes, and socks, I had the look of a city girl, very different from the village children, most of whom were barefoot, their hair uncombed and without ribbons. My grandmother was wearing her usual ghutwa, her face totally concealed beneath a thick veil.

The young children followed us on both sides of the street, quiet and curious. I noticed a young girl standing on a platform who stuck out her tongue, making fun of me. A young man, showing off, shouted at the children, telling them to go away and saying, “It is a shame to behave this way.” But the children kept following us, on both sides of the street, until we reached a grocery shop that was playing an Egyptian song. My grandmother stood in front of the shop and greeted the owner like a man would, saying, “Peace be upon you.”

The shop owner seemed surprised and answered in a somewhat exaggerated manner, curious but welcoming: “Peace upon you, too. May God’s mercy and His blessings be with you.”

Then he turned to the children and scolded them. “Go away, all of you. Your behavior is shameful.”

The children paid no attention to him and continued to examine us.

My grandmother, clearly upset, said, “Tell us where Umm Nayef’s house is, may God bless you.”

One of the children shouted, “I know where Umm Nayef’s house is!”

“We know, too!” others chimed in.

The grocer pointed and said, “It is at the end of the street, to your right. One of its walls is made of bricks, surrounded by olive trees.” He then shouted at the children, telling them to go away.

The children ran in front of us toward the house to announce our arrival to Umm Nayef and to prove to us that they truly knew Umm Nayef, as well as her house, located in the midst of the olive trees.

Umm Nayef came out into the street to see who was visiting her. Her sleeves were pulled up, leaving her arms uncovered, while one side of her dress was tucked under a thick belt made of saya. Her pulled-up dress revealed another garment, dusty white, that reached her feet and resembled a serwal. Her hair was parted in the middle and combed into two thin black braids, without any sign of gray, despite her old age. She was as old as my grandmother, maybe older, but she still had some of her teeth, and there was a green tattoo on her chin.

She covered her eyes with her hand to shield the bright sun and allow her to see who we were, while the children surrounded her, waiting impatiently for us to arrive. She wanted to know who was visiting her but they wanted to know who we were. As soon as she saw us and recognized us, she clapped and put her hand before her mouth and ululated discreetly, uttering low and short sounds. They were meant to express her joy and surprise and show how honored she was by our visit. Here was this city lady, from a well-known family, visiting her—her, a poor country woman who made a living selling milk and green wheat! Was there a higher honor?

At that moment, I felt someone’s hand tugging at my dress. Frightened, I quickly tightened my dress around my knees and turned. I saw the little girl who had stuck out her tongue at me earlier. She was very young, younger than me, and much shorter, her bushy hair uncombed. Her face was on the dark side. She was wearing a shapeless, buttonless dress, mulberry colored, with yellow flowers, and she was barefoot. Our eyes met in a cautious look. I was scared and shy, while she seemed fearless, looking at me with expressionless eyes, still pulling my dress. We entered Umm Nayef’s house, and I was immensely relieved to get away from the little girl and the gang of children.

Umm Nayef’s house consisted of one large, dark room, with mattresses spread on the floor. In a corner that seemed to serve as a kitchen was a large water jar. A door led to a courtyard where a few sheep, chickens, and rabbits roamed.

We sat on the mattresses and drank tea with sage. The two women were whispering, and I tried to follow their conversation, but Umm Nayef turned and told me that the goat called Wadha had given birth to a female kid, the size of a cat, and asked if I would like to see it. I glued myself to my grandmother and shook my head shyly; I was curious, but I wanted to listen to the conversation. Umm Nayef insisted that I should go out to watch the children play the game “hit and run.” But I did not comply and stuck close to my grandmother, who told her, “Let her stay. It doesn’t matter.” Upon hearing those words, Umm Nayef began talking in riddles, saying, “They arrived, they left, they came down, they ate, they drank and celebrated the wedding among the olive trees and the piles of wheat, but they burned down the wheat.”

Surprised and curious, I asked, “Grandma, who burned the wheat?”

My grandmother nudged me gently to stop me from talking and said to Umm Nayef, with deep interest, “And then?” Umm Nayef went on talking, but I only understood bits and pieces.

We were still drinking our tea when Umm Nayef’s house was invaded by women, each with a different request. One wanted to borrow a few eggs, another came to buy milk, and another came because she missed Umm Nayef and wanted to see her, and a fourth, and a fifth, until the room was filled with women of all ages, sitting on the mattresses. As the number of women grew, I stuck to my grandmother, who seemed like my elementary school principal. She knew how to talk, using the language of the Qur’an as well as proverbs, and commenting like a school principal would. But it took only a few minutes for the situation to change, as stories of valor and courage were heard: one woman said that she hid the dynamite and the gun under the manure, while another said that she hid them under the dough. A third woman told us that she hid the revolver in the milk jug, and when a British soldier came by, the ground opened up and the fedayee got hold of the revolver, shot the officer, and returned the revolver to its place; then she began shouting, “Milk, milk, who wants milk?”

Finally, the oldest woman of the group, who seemed to hold an important place in the village and in her contact with the revolutionaries, said, “Umm Wahid, your son, may God bless him, is the leader of the youth. People consider him a hero, but we cannot say that we have seen him. Sometimes people say that he fought the British and ambushed them, killing ten, maybe twenty men. People talk and we listen, but we cannot say we have ever seen him. I am ready to look for him, for your sake. I will inquire about him until I find him. Would that please you, Hajjeh?

My grandmother shook her head, disheartened and discouraged, far from looking like a school principal, or even an ordinary teacher of modest means.

Call for Reviews

If you would like to review the book for the Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya, please email info@jadaliyya.com

210302041815655~.jpg)