Al-ḥusin Al-gedari died at roughly 100 years of age on 28 April 2023. Born in the late 1920s, Al-gedari was a native of Lamḥamid, a Saharan village of less than 3,000 in Morocco’s Anti-Atlas Mountains. The passing of this rural, illiterate man, living seemingly at a remove from world events, might easily go unnoticed. The world is full of important people who die every day, and the news does not leave room for people like Al-gedari. Nonetheless, Al-gedari was among the many ordinary people who were at the very center of global history during World War II. Not only did he witness the war: he had a perspective that highlights the war’s complex, intersectional agony.

Lamhamid, Foum Zguid, Gedari’s birthplace. Credit: Majdouline Boum-Mendoza.

Like thousands of North African Jews and Muslims, Al-gedari experienced Vichy French rule in North Africa. Al-gedari was also a witness to the Allied Landing in North Africa, and experienced the complex consequences of the Allies’ war against fascism.

The story of the liberation of North Africa from fascist rule has been told by the region’s elite. By contrast, most North African and West African victims of fascist rule like Al-gedari have never had their testimonies systematically collected or listened to. After the war, many North African soldiers like Al-gedari returned to their villages and hometowns, slipping into historical oblivion. Yet even in the most remote area in North Africa, one can find a former colonial conscript, now in his most senior years, with vivid memories of his time as a forcibly-recruited soldier. Al-gedari’s passing offers an opportunity to honor him and, through him, other forgotten children of history.

Born in the interwar period, Al-gedari had a love of history since an early age. He always had a radio with him, whether at home, in the market, or while riding his donkey to the fields. Al-gedari didn’t just listen to the news: he also had opinions about what he heard on the radio. This obsession with the news followed him into his old age.

Gedari listening to his radio, 2021. Credit: Majdouline Boum-Mendoza.

Listening to the news of the second Gulf War, Al-gedari became so obsessed with Saddam Hussein’s stand against the western coalition that he sought to name his son Saddam. Local authorities saw this as an inflammatory request, particularly given the pro-Kuwaiti position King Hassan II had taken since Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iraq’s neighboring country. For his part, Al-gedari was able to reconcile his fascination with Saddam with an apparent absence of anti-American sentiment. He loved to boast, with characteristic good humor, of his fondness for American politics. He also remembered, with appreciation, the role the Americans played in liberating North Africa from fascist occupation. Al-gedari wore a sense of global connection on his sleeve.

Al-gedari was a young adult when the Second World War broke out. A lover of history, he now found himself at the center of a global drama. The peoples of North Africa were subjected to three fascist regimes during WWII. The populations of the three French colonies of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia found themselves under the control of Vichy France, the collaborationist regime that ruled southern France and its colonies from 1940-1944. The Nazi SS exerted direct control over Tunisia from November 1942 to May 1943, while in Libya, Mussolini’s fascist Italy ruled. These regimes systematically imposed their racist, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, and anti-Black laws upon the peoples of North Africa.

In an oral history Aomar Boum conducted in 2019, Al-gedari spoke of the terrible famine that took root in his region during the course of the war. The people of Lamḥamid starved as a result of a state-engineered famine; hunger changed their bodies forever, epigenetically altering even the health of their future offspring.

Remote as Al-gedari’s town was, those that died did so in obscene company. Roughly six million people died of starvation, malnutrition, and associated diseases during WWII. The number is higher than that of wartime military fatalities.

In North Africa, food scarcity had multiple causes. A dreadful drought wracked the landscape. The Third Reich implemented extractive and exploitative policies in its occupied territories, causing local shortages of housing, heating, electricity, and medical supplies across regions under its control. Fascist Italian and Vichy French authorities echoed these policies. They plundered food from their colonies in North Africa, West Africa, and Southeast Asia, causing widespread starvation and malnutrition. Finally, the disruption of the North African food supply was further impacted by the Allied landing in 1942, which brought thousands of hungry troops to the region. The result of these circumstances was death by famine and related diseases for millions of people like Al-gedari.

In 2019, Al-gedari recalled that and “the years of hunger [1939-1945], otherwise known as the years of rations (‘am al-bun), killed so many people and destroyed so many communities in our region…. A combination of war, typhus, drought, and famine was like a wildfire that struck the southern hinterlands. Palm trees did not yield that many dates . . . and the few that did grow were confiscated by tribal lords and distributed between the pasha of Marrakesh El Glaoui and the French colonial administrators. News circulated that Hitler stole the food of France to feed the German population, forcing France to take native North Africa’s food shares…”

In Al-gedari’s telling, Muslim locals understood famine to be part of a wartime chain reaction, with Germany’s theft of France’s foodstuffs resulting in the Vichy regime’s plundering of the food supply in North Africa. His experience taught him what most historians and testimony-gathering institutions have not appreciated, which is that the experiences of the peoples of wartime North Africa were inextricably connected to those of Europe. In his small desert village in the south of Morocco, Al-gedari lived this reality and made sense of it—without being informed about the global context for his town’s famine, or its geostrategic implications.

Al-gedari saw and rationalized the pain of his community. Whatever happened in the broader world had material effects on real people he knew and loved. During the war, the very space of the desert became a last-resource source for food. Al-gedari remembers that “as the food shortage grew, people started looking for edible grass, especially as the slow supply of American wheat did little to stop hunger.” Meanwhile, “typhus struck communities, killing hundreds of families…” The shortage was widespread, and even “clothes were rare. People walked barefoot.”

While they felt the material impact of WWII, hinterland communities like Al-gedari’s were sheltered from the racist, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, and anti-Black policies that the fascist regimes meted out on other North Africans. Elsewhere, the Vichy, Italian fascist, and Nazi regimes stripped North African Jews of their French citizenship (if they had it before the war), pushed them out of the occupations, stole their businesses and property, and subjected many to forced labor. But these laws were not consistently applied in the remote anti-Atlas Mountains.

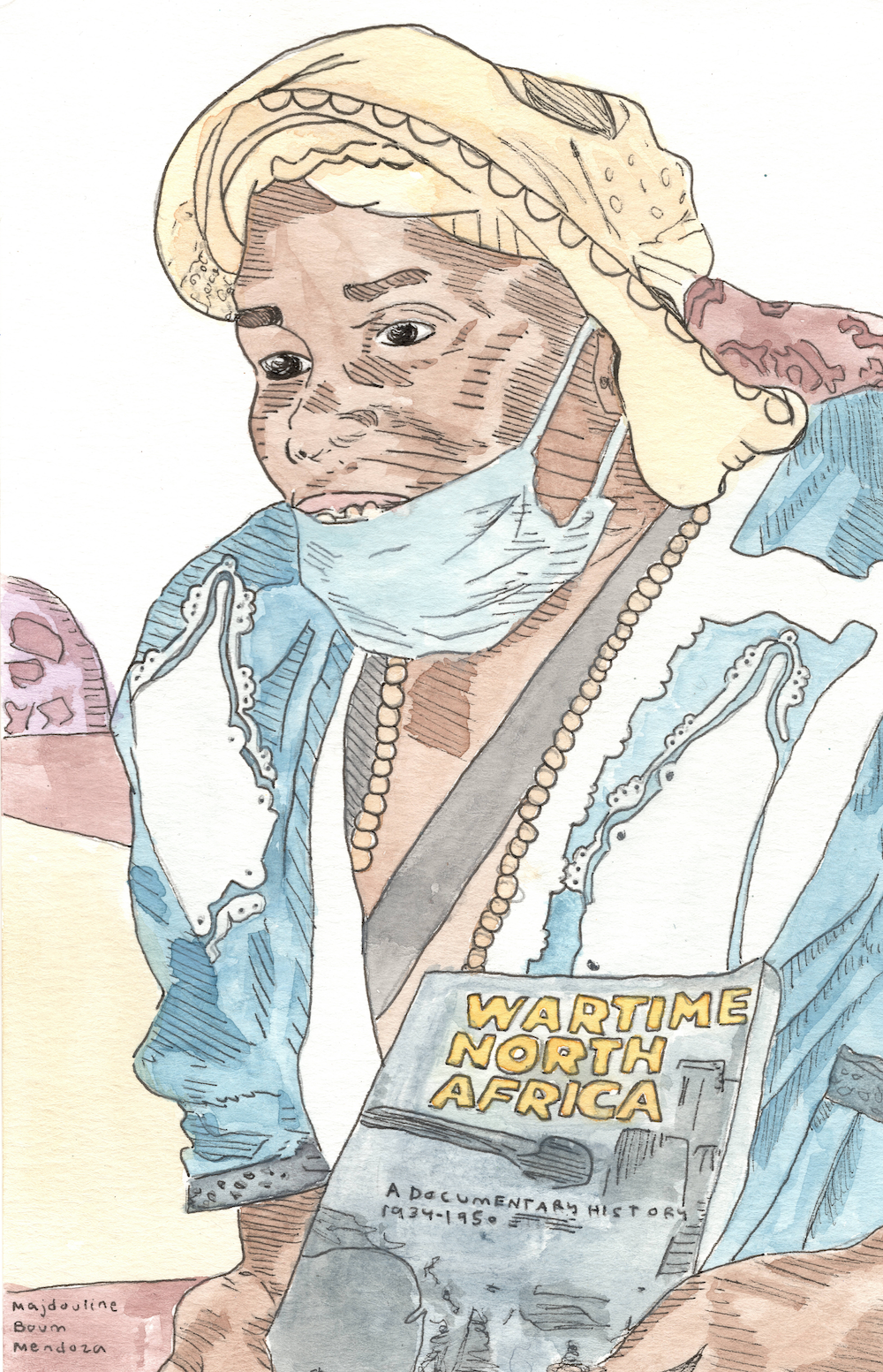

We have shared Al-gedari’s story in a recent book that amplifies the wartime voices of North Africa’s Jewish and Muslim residents alongside the experiences of the refugees, political prisoners, forcibly inducted West African boys and men, and subjects of slave labor whose paths wound through wartime North Africa.

Gedari cherishing his name in print, December 2022. Credit: Majdouline Boum-Mendoza.

After our book, Wartime North Africa, was published, we shared a copy with Al-gedari. He proudly showed the book off to his neighbors, keeping it wrapped in paper to protect it from harm. So valuable was the book to Al-gedari that he obliged people to to wash their hands before touching it. Al-gedari was moved that his story had been heard. It would have made him even prouder had it been written earlier.

The anticipation of a world without Holocaust witnesses is a daunting one, raising the powerful question of how and whether this cataclysmic event could be understood in the absence of witnesses and their first-hand accounts. This existential question has served as a call to action. It has prompted a flurry of testimony gathering, a rush to support survivors in financial need, and the production of cutting-edge, interactive technology and language processing designed to keep witnessing alive in the absences of living witnesses. At the same time, the accounts of witnesses (and of witnesses of witnesses) and complex theorizations around intergenerational trauma and postmemory have come be central to Holocaust Studies.

Al-gedari was not a Holocaust survivor. He was not threatened by the Nazi death camps (though hundreds of North African Jewish women, men, and children and even some North African Muslims did perish there). Still, Al-gedari’s story was not divorced from events that unfolded in Europe. He listened to history, witnessed it, and saw its impact.

Al-gedari is no longer here to tell us his memories of WWII. And only a fragment of North African experiences of WWII have been recorded. The ‘walking histories’ of this episode are slowly vanishing. There are other Al-gadaris who have lived and died throughout North Africa. Their stories should not die with them.

Al-gadari’s story reminds us that telling local and indigenous stories is a humanistic necessity. Storytelling is not just a private act, but a communal one that creates a community of witnesses who sustain the legacy of the storyteller. Recognizing World War II victims like Al-gedari honors those who were never invited to speak their truth. It also demonstrates how much history remains to be preserved. Just as a flurry of attention, worry, and anticipatory dread surrounds the death of the last surviving Holocaust survivors, so too should we treasure the perspective of North African witnesses–and mourn the lost stories we are too late to record.

The Malian novelist Amadou Hampâté Bâ proclaimed in 1960 that “every time an old man dies [in Africa], a whole library has burned down.” Each Al-gadari who passes represents rich knowledge lost to history. We are running out of time to record stories like his, and to memorialize ordinary individuals like him who have been written out of history.