Following the prolonged mismanagement of municipal solid waste in Greater Beirut in the summer of 2015, garbage and the mundane daily consumption of goods start to manifest as an influential element within the spatial organization of the urban landscape. While large amounts of trash piled up at street corners are stored along riverbeds, hidden, and dumped across forests, valleys, and the seashore, flows of industrial goods and the structure of a city become evidently entangled. As the flow of industrial cycles is interrupted, or breaks, the seemingly distinct spheres of production, distribution, consumption, and disposal of waste emerge in a single space. One shits where one eats. Trash no longer migrates beyond the visible spectrum of the city to be buried in distant landfills, but instead decomposes and releases stench fumes a few meters away from where it is consumed. Through the newly sedentary discharge of urban life, it becomes evident that mundane habits, such as shopping for food, have a direct impact on the environment. However, this does not weigh on the industrial process as the flow of production/consumption does not slow down. Instead, it only exhibits its discharge in a momentary relapse until its renewal. The trash, as residuum, carries on with its own production process as it decomposes into smaller particles that infiltrate the ether, the soil, the water, marine species, and the human body. It has transformative consequences for the receptive body, which will then again tap into an endless chain of transformations, or production. The receptive body is the body of the earth: the biosphere. Simultaneously, the receptive body is capital as value is extracted from trash. In the aftermath of the 2015 Greater Beirut trash crisis, deposits of trash accumulated over a period of two years are used as filling material in a coastal regeneration project that doubles up as a temporary solution to the crisis. The state of emergency ensuing from a prolonged crisis is instrumentalized to swiftly implement a hazardous yet valuable land reclamation project. The method of construction bypasses acceptable standards and the environmental consequences are deadly for the sea, marine life and fishermen’s livelihood. At the same time, construction workers, engineers, and fishermen are exposed daily, throughout the length of the construction works, to serious health threats.

As the flow of industrial cycles is interrupted, or breaks, the seemingly distinct spheres of production, distribution, consumption, and disposal of waste emerge in a single space.

In the heat of the summer of 2015, garbage begins to proliferate across the country following the closure of the only sanitary landfill in the nearby town of Naameh catering to the solid waste management of Greater Beirut. This is not the first trash crisis. From the very onset of the Lebanese civil and regional war in 1975, informal practices of waste dumping in open pits or by the sea were frequent, namely in the notable sites of the Normandy bay in the city center and in the industrial neighborhood Bourj Hammoud north of Beirut. The massive Normandy dump was transformed in the 1990s after the war, while the Bourj Hammoud site was not granted a similar concern. Nonetheless the former will serve as a precedent for the latter twenty-five years onward. The Normandy site, located within the perimeter of the city center’s post-war reconstruction plans, demonstrates an ostensibly magical transformation from a five million m3 trash dump to a 1.7 million m2 plane dubbed the “Beirut waterfront district,” estimated at a value of around ten billion dollars. From a real estate point of view, Normandy is considered to be the proud coup de maître of the developing company called Solidere in charge of the city center’s post-war reconstruction. A study of the composition of the Normandy dumpsite prior to its transformation confirms the content of hazardous waste and the details on the transfer of the toxic waste remains unclear. In spite of Solidere’s claim in their corporate magazine that the waste was successfully relocated outside Beirut in accordance with public authorities, recent studies have shown that the land contains a high level of toxicity. The projected real estate success of this new territory is still in limbo, waiting for the next economic jumpstart.

Fig. 01. Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh land reclamation in process (Source: Google Earth)

The trash crisis of 2015 is akin to the one of 1997 in the appeal for the closure of a highly contested landfill while the solution proposed by the government following the 2015 crisis is again a temporary one. The failures of the government to instigate a well-thought long-term solution is due to their refusal to accept any viable sustainable waste management method besides landfilling regardless of the difficulty to find vast vacant land remote from inhabited areas. Another reason is the privatization of waste management practices and the diversion of funds away from municipalities. When garbage collection is halted for weeks on end, the toxic juices of stale fermented trash infiltrate cracks in the asphalt, the soil of the field, the water of the river, and alarming levels of carcinogenic dioxins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons proliferate in the air. In the event of the prolonged crisis, chaos, uncertainty, and fear take hold of everyday life witnessing weekly protests, burning trash, black smoke and heightened paranoia in regards to potential health threats. As a long overdue solution, the government kicks off the construction of sanitary landfills on the sea, extending landmass onto water. Two sites are chosen by the sea: Costa Brava south of Beirut and the site of Bourj Hammoud’s old trash hill north of Beirut. Bourj Hammoud’s construction method is based on a simple “cut and fill” concept: it consists of dismantling the old trash hill and spreading it into the sea, extending the land reclamation further east to the adjacent neighborhood of Jdeideh and into the Mediterranean, reaching a total area of 600,000 square kilometers. [Fig. 01] One of the architects of the project reluctantly conceded his doubt during a private meeting, “…although we are following the necessary marine protection, I am not convinced by the solution of further extending the spread of old trash in the sea, but we do not have any other choice because we do not have a government that can be decisive on a specific location [for a landfill].” It was later confirmed that they are not taking the necessary measures for marine protection. During a construction site visit, the project supervision engineer admitted that they have been dumping trash into the sea prior to completing the construction of a breakwater barrier. He blamed this discrepancy on a forced reshuffling in the schedule due to the urgency of the situation.

Fig. 02. Dismantling the Bourj Hammoud trash mountain (Fadi Mansour, “Dreamland” video still, 2017)

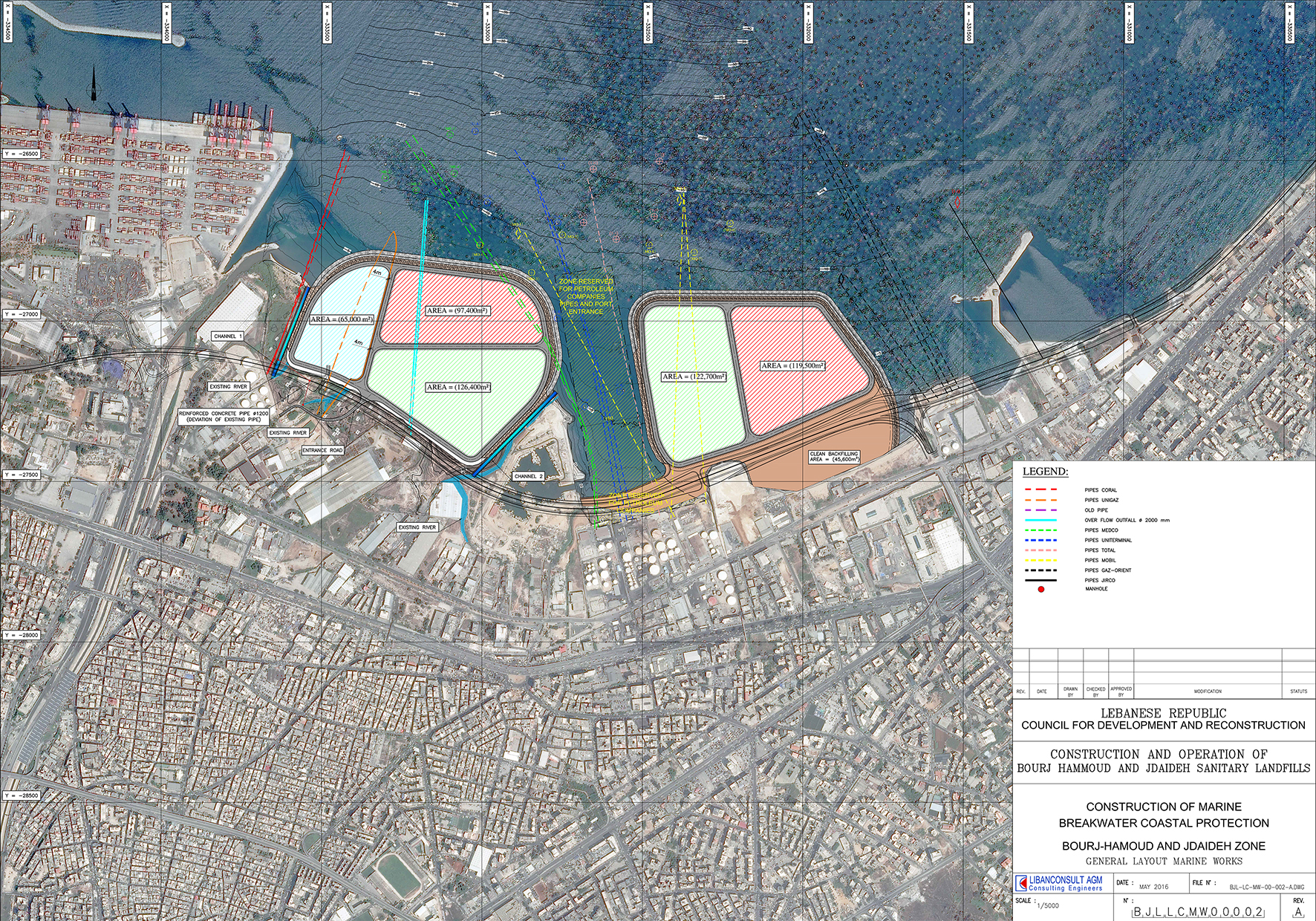

The old trash hill of Bourj Hammoud was an uncontrolled dumpsite since the beginning of the war in 1975, and then became an official landfill after the war ended in 1990, until its closure in 1997. As it was never built as a sanitary landfill, it leaked “an estimated 120,000 tons of leachate annually” directly into the sea, “destroying sea life within a radius of hundreds of meters,” and released methane gas into the atmosphere as a product of the fermentation of solid waste. Dismantled after twenty years of fermentation, the guts of this highly toxic hill are exposed and in close contact with the atmosphere, the sea and construction workers, as dozens of excavator trucks work their way through the belly of a forty-year old history of muck. [Fig. 02] An unearthly mixture of dark brown, thin protruding colored plastic film and unidentifiable chunks of different sizes and colors is the “dirty” backfilling material for the landfill. The construction method distinguishes between “dirty” and “clean” backfill, where “clean” backfill is simply sand. The plan for the new land consists of five large plots: two landfill areas of 125,000 m2 each, built with dirty backfilling and expected to become public gardens once stacking saturation of fresh trash is reached; two plots of 110,000 m2 each of clean backfilling for future urban development; and an area of 65,000 m2 dedicated to a long-awaited sewage treatment plant for the city of Beirut. [Fig. 03] Prior to gutting out the old trash hill, the “environmental impact assessment” conducted consisted of a gas study to evaluate the decomposition of the old waste, but did not include an analysis of toxicity. The gas study assumes that the main constituent of the hill is organic matter and thus only studies the decomposition of this inert matter, which is the least toxic component. What the study also shows, without mentioning it in the report, is that almost all of the gases were released into the atmosphere, although they should have been captured and burned while the leachates were dumped in the sea. There is no analysis of the chemical composition of the landfill, nor of the solid matter that was extracted or the leachates, of which only the level was measured.[1] Regardless of the lack of toxicity tests on the old waste, the consequences for sea life are evident, as testified by the fishermen of Bourj Hammoud’s port. The fishermen, protesting against the project since its inception, are the ones suffering the direct consequences for their health and livelihood, along with sea and marine life. Chemist Dr. Najat Saliba explains that the most obvious toxic waste in the old hill consists of metal components, pesticides, oil transformers such as PCB polycyclic biphenyl from industrial plants, and chlorinated substances from the degradation of plastics. She explains that because of leachate leaks, there is an abundance of nitrate in the sea. As a result, there is an ample increase of phytoplankton microorganisms that float on the top layer of seawater, forming a layer that blocks sunlight, ensuing in oxygen depletion of the water body. [2]

Fig. 03. Plan of the Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh sanitary landfill and land reclamation project (Source: Lebanese Republic Council for Development and Reconstruction)

The industrial coast of Bourj Hammoud has been perpetually subjected to lethal expansive pollution, from untreated sewage discharge for decades, to animal organ remains from the nearby slaughterhouse, to the flushing of oil pipes directly into the sea from nearby hydrocarbon companies, to the illegal smuggling of toxic hazardous waste during the war of 1975-1990. Proponents of the project say that an extra 3.5 million m3 of old waste would not make a major difference to the already ruinously polluted sea. It evidently aggravated the situation, as testified by the fishermen who have engaged with this sea for decades and witnessed the different degradation degrees of marine life. This situation is by no means particular to this specific site, as ecological disaster has inadvertently become a recurrent phenomenon across the globe, to the extent where it is met with a lack of concern.[3] There is still a general tendency to believe that the ecological faux pas will be redeemed. This false belief operates within a particular perception of a world, one of a capitalist profit economy that predates our understanding of global warming. This would be a world that posits capital and nature as the essence of reality. Timothy Morton calls it “capitalist essentialism,” where the concept of nature is the accomplice of capital, as “both exist in an ethereal beyond. Over here, where we live, is an oil spill. But do not worry. The beyond will take care of it.” He gives the example of the aftermath of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the unsympathetic response of the CEO towards the disaster, saying that “the Gulf of Mexico was a huge body of water, and that the spill was tiny by comparison. Nature would absorb the industrial accident.”[4] Morton points to the metaphysics involved in the BP CEO’s claim, hinting at the inherent belief that nature would solve the issue by itself. Lebanon’s minister of environment reacted in a similarly callous manner, pointing out the inevitability of the situation by way of a divine-like disjunctive syllogism: “The agreement between the contractor and the (governmental) Council for Development and Reconstruction requires reclaiming the sea. Therefore, waste should be buried in the sea.” Such a comment can be dismissed as nonsensical, biased and corrupt, but this is exactly how the project was led to fruition: as a disjunctive synthesis.

The chemical breakdown of decades-old trash, whilst discharging toxic leachates and methane gas into the sea and air, led to the creation of a composite material that later formed a substitute for soil in the production of new land. In addition to this new alchemical matter, fresh trash piles from a prolonged solid waste mismanagement were also added to the fill. This new spread onto the sea, whose dismissed lingering toxicity pursues ecological mutations, will be applauded as a successful real estate endeavor and coastal urban regeneration. The production process of this new land undeniably consummates an intimate relationship with flows of toxicity at all stages of its coming into being and into the future. The Normandy land reclamation is the precedent and the libidinal drive to the creation of its successor, and could very well keep on fulfilling this role. Ever since its completion, the Normandy, through its celebratory evaluation, was essentially becoming anticipatory, in as much as it was being redeemed for its flawed production process.[5] What outlives the Normandy disaster is a clean stretch of land praised for its value, while its toxic history is rendered invisible. In order to break away from a potential repetition of the same process, I believe it is important to work on the invisibility of the Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh transformation, where the inscription of the project within the urban narrative should remain connected to its material composition and process.

[1] Elias Azzi, expert in waste management systems and PhD-candidate in industrial ecology at KTH Sweden, email exchange where he kindly shared his personal analysis and remarks on the gas and geotechnical reports, August 2017.

[2] Najat Saliba - AUB Chemistry department, notes taken during a meeting and email exchange, 17 August 2017.

[3] See Saskia Sassen, Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy (London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University press, 2014) on the extent of dead land and dead water due to pollution of all sorts, on a scale our planet has never seen before, and in relation to a systemic deepening of advanced capitalism.

[4] Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 115.

[5] For evaluation as anticipation, See Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “7000 BC: Apparatus of Capture,” in A thousand plateaus (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 493-550.