The political system in Jordan features 101 municipalities. More than half of Jordan’s municipalities are currently experiencing an acute deficit and concomitant high degree of indebtedness. In 2017, the total municipal debt amounted to 130 million dinars. Many municipalities spend most of their budget on municipal employees’ salaries, which highly restrains their scope of action in the face of indebtedness. Zarqa, the second most populated city after Amman, is a case in point. When the new municipal board was elected in August 2017, the total public debt of the Zarqa municipality amounted to forty-two million dinars. Its annual budget that year was twenty-eight million dinars, seventy-five percent of which went to employees’ salaries.[1] Such debt effectively crippled the municipality’s daily operations, including the delivery of urban services. This problem reached a crisis point in January 2018 when the Jordanian Social Security Fund decided to suspend the health insurance of Zarqa’s municipal employees. This development followed the previous municipal board’s decision to stop transferring employees’ social security contributions to the Social Security Fund. The amounts were withheld from employees’ paychecks, but “disappeared” from the municipality’s accounts. This alone resulted in a thirteen-million-dinar debt owed by the Zarqa municipality to the Social Security Fund—a debt the municipality continues to be unable to pay back. After months of negotiations led by Zarqa Mayor Ali Abu al-Sukkar, a leader of the Islamic Action Frontand a well-known critic to the Jordanian regime, the public Cities and Villages Development Bank (CVDB) granted the municipality a loan for 11.5 million dinars. The CVDB loan came with specific budget stabilization conditions. It, therefore, inaugurated a new era of budget austerity for the Zarqa municipality.

In this article, I focus on local politicians’ responses and strategies to overcome the new austerity measures. Through which means do elected municipal members sustain their political legitimacy? How do they manage to maintain public services and to implement new urban projects in the absence of public funds? What are the consequences of these practices the local configurations of political power and public action? Recent developments in municipal governance have facilitated the emergence of new local clientelist networks and informal public-private partnerships. These enable local politicians to rely on alternative private resources in a context of shrinking public resources.

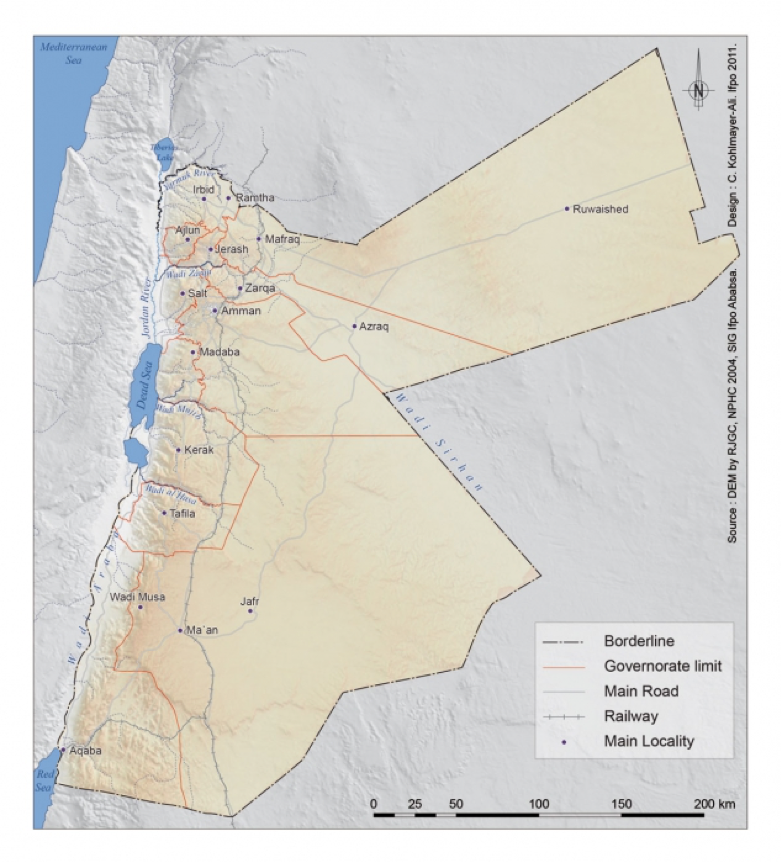

[Map of Jordan. Excerpted from Myriam Ababsa (dir.), Atlas of Jordan, 2013.]

Centralization, Municipalities’ Financial Dependence, and Indebtedness

In Jordan, as in many other places, institutional and financial factors constrain elected municipal officials’ scope for action. High levels of state centralization, financial dependence on the central government, and the state-imposed privatization of urban services have rendered most municipalities unable to exert direct control on most sectors of urban public life. Combined with severe indebtedness, Jordanian municipalities can neither cater to their residents’ needs nor guarantee efficient urban planning policies. The so-called decentralization reform of 2015, which created a newly-elected council at the regional level, has contributed to this dynamic by further subordinating municipalities vis-à-vis the central government.

The Municipality Law of 1955 allocated significant prerogatives to Jordanian municipalities in terms of tax collection, urban services (e.g., water, electricity, garbage collection), and social services delivery. Unsurprisingly, such institutional arrangements were established at a particular highpoint of popular mobilization and prior to what many historians define as the critical period in the consolidation of Jordan’s authoritarian system of rule.[2] Since the 1980s, the regime has progressively dispossessed municipal authorities of their service-provisioning power, transferring them to a variety of other public and private actors.[3] The government forced the devolution of most of these prerogatives to ministries, other public agencies, and private actors, justifying it in terms of municipalities being unable to perform these tasks. Today, the Ministry of Water and Irrigation and the Jordan Electricity Authority operate water and electricity delivery, respectively. At the same time, the Ministry of Transport is responsible for local public transportation (bus) services. Since the late 1990s, international development organizations encouraged public-private partnerships, which reinforced the marginalization of municipal actors. Thus, until today municipalities are tasked to facilitate coordination between ministries, public agencies, and private companies. They only retain a few of their original responsibilities over services delivery and urban planning such as street maintenance and garbage collection. The latest 2015 Law on Municipality confirmed this status quo.

Official justifications for such dynamics insist on the allegedly apolitical cause of service delivery efficiency. Yet when subjected to closer scrutiny, reasons are far more political than administrative. Even the World Bank has been forced to admit as much. A 1995 report from the multinational institution, released soon after a Jordanian amendment that transferred several key municipal responsibilities to central ministries, stated that “the driving force behind the municipalities draft law appears to be an intent to alter local political forces, in part to overcome changes in the political balance caused by refugee camps."[4] Such analysis took seriously the regime’s attempt to undermine the broad electoral base of the Islamic Action Front (IAF). The Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood created the IAF in 1992 to compete in what were the second legislative elections held since the regime ended martial law in 1989. Reforms in municipal institutional arrangements were partly an attempt to prevent local opposition-controlled representative institutions from enjoying “too much” power. In this sense, they can be viewed as a corollary to the parliamentary election system the regime introduced in 1992 to prevent opposition parties from winning a significant number of seats.[5]

Jordan is currently one of the Middle Eastern states wherein municipalities receive the lowest share in public expenditures. Only three percent of the central state budget is dedicated to municipalities, yet central fiscal transfers represent more than half of the municipal revenues.[6] In practice, these transfers, primarily based on a redistribution of fuel taxes, do not follow any pre-defined distribution rule. The regime strategically uses them to favor municipalities dominated by loyalists.[7] Fiscal transfers allocated to municipalities are one of the regime’s instruments to ensure some regions’ political support, as part of a long-term clientelist arrangement.[8] In contrast to Mafraq and Karak, Zarqa is one of the most disadvantaged municipalities in terms of tax transfers. This is despite the fact that the Zarqa Governorate features one of the highest poverty rates of the country. Zarqa municipality is demographically dominated by Jordanians of Palestinian origin, and above all, it is one of the strongholds of the Islamic Action Front.

Municipalities also draw revenues from property taxes, which are assessed on rental prices, building permits, and commercial leases. Jordan’s largest municipalities—Amman, Zarqa, and Irbid—collect these taxes directly. However, all municipalities suffer from insufficient tax collection. This is due to an inability to properly assess the amounts of tax owed as well as to collect the latter. It can also result from municipal officials’ or the Ministry of Finance’s nepotic practices.[9] The same issue arises with other taxes that form an even smaller part of their revenue flows: professional taxes, required for any artisanal, commercial, and industrial occupation besides obtaining a municipal license; and taxes on garbage collection, paid by households, enterprises, and independent entrepreneurs. Such inefficiencies prevent municipalities from reaching sufficient revenues and consequently worsen their budget deficit and indebtedness.

Subordination to central state authorities further constrains municipalities in their budgetary choices and strategies. The 2011 Municipality Law requires municipalities to obtain an authorization from the Ministry of Municipal Affairs (MOMA) for any budget decision or financial transaction. The annual budget needs to be approved by the MOMA, after a detailed review conducted by the CVDB. Throughout the year, the MOMA has to approve all expenditures above five thousand dinars as well as any expenditure that did not appear in the initial budget estimate. Any budget expenditure demand implies for the municipality a long bureaucratic process that weighs on municipal action efficiency.[10] This centralized control over local spending has negative consequences on the quality of service delivery and urban planning at the municipal level. It also impacts municipalities’ relationships to their constituents. As municipalities appear unable to cater to the needs of residents, the latter turn away from the local institutions. The resultant lack of trust in local institutions can partly explain difficulties in tax collection, as well as low turnout in local elections.[11] In 2017, the participation rate reached 31.7 percent of the 4.1 million voters across the country. This contrasts with the 36.1 percent turnout rate for the 2016 legislative elections.[12]

New Clientelist Networks and Informal Public-Private Partnerships

All Jordanian municipalities are under tight budget constraints and closely controlled by the central government through a range of financing mechanisms. This configuration is particularly true in the case of Zarqa. Besides being disadvantaged in terms of fiscal transfers from the state, the municipal authorities of this 700,000-inhabitant city were forced to implement strict austerity measures in order to achieve a balanced budget. Zarqa’s elected officials undertook a variety of strategies to overcome budget cuts and carry on with urban planning projects to sustain their political legitimacy. Local officials demonstrated an ability to use their personal and professional networks in order to mobilize alternative financial resources since they could not rely on the municipality’s budget. They entered into semi-formal and personalized agreements with private actors from their neighborhoods. To some extent, such a strategy required them to negotiate between legality and illegality, formal and informal politics.[13] As a result, members of the municipal council established new clientelist networks that were outside official register of politics, though the resulting urban projects are very much public.

One way of understanding these informal relationships between private economic actors and public authorities is to use Clarence Stone’s concept of an “urban regime.”[14] Stone shows how the “capacity to govern” can be maintained through the creation of new coalitions where governmental and non-governmental partners own resources they exchange between each other. Elected politicians want to benefit from the financial support of private actors, who aim to influence local urban planning. What is most productive about Stone’s argument is its emphasis on the officials’ creativity in maintaining their governing capacity. This is precisely what can be observed in Zarqa. By manipulating the rules of municipal public action, officials find creative ways to make informal clientelist arrangements, where they can access private resources in exchange for few public resources.

There are two main forms of informal public-private partnerships. In the first, the municipal official mobilizes his friendships or other networks to identify local businessmen prone to cooperate. Negotiations take the form of an informal conversation, and aim to establish a temporary alliance between the two partners. The municipal official will generally engage with a shop or business owner seeking to carry out a small urban development project to benefit the residents of the city or the neighborhood. The municipal official sees the opportunity to turn a private initiative into a publicly-endowed project, which he can then use as a legitimation strategy. In exchange for claiming ownership over the project, the local politician provides his private-sector partner with the material resources necessary to implement the project (i.e., permits, workforce, and infrastructure). For instance, one official explained to me:

We received a bridge. It was a donation from a citizen of Zarqa. It cost 17,000 dinars. Well, it is a businessman. His business is really close from here. He is a really good friend and he told me “I will give this bridge because it is a win-win situation, my business is next from here and I need this bridge and you can help me building it.” And it’s true. I can make all my employees available to him.[15]

The municipal official can claim, on social media for instance, this achievement to his constituents and supporters. Following Stone’s analysis, we find that the private actor determines the local official’s scope of action while the latter sets the terms of the agreement.

The second type of informal public-private partnership puts the municipal official in a more compromising position, as it implies an actual violation of the law or misappropriation of public money. The empirical material illustrating this configuration was collected at the end of the interviews, when the trust relationship was well established and when my interlocutor was keen to share with me his creative abilities. In this case, the two partners do not know each other prior to entering into an agreement. Consequently, the reward for the private actor needs to be much bigger in order to convince him to collaborate. For instance, building permits, which are directly delivered by locally-elected councils, are one of the few resources that can be offered to a private individual willing to work with the municipality. For instance, one of my interviewees shared with me: “I tried to be creative. I meet with investors and I ask them to fix the streets, and I tell them ‘If you accept to fix them, I will accept some illegal constructions.’”[16] Aware of his unlawful behavior, he insisted on the necessity for him to enter into such an agreement to overcome the municipality’s strict budget constraints. A few months before, the central government prevented the municipality from spending two million dinars on asphalt to repave the streets of the city. Zarqa is notably famous in Jordan for the disastrous state of its streets, and their reparation is always one of the residents’ most pressing demands.

Other members of the local council imagined another illegal and informal mechanism, though they always introduced it to me as a legitimate and legal process. However, every time I was asking for further details, answers were getting more elusive. This is how one of the members’ explanation looked like:

Budget is insufficient to maintain the services. I suggested . . . that we take from businessmen or from shops owners something we could call “service return.” These owners normally have to pay taxes to the municipality, in cash. But I thought that we could ask them to pay those taxes in the form of materials, to pave the streets, plant trees. If we need something, we can ask them.[17]

Since the loan granting, in order to expend the municipality’s available funds, each municipal member was asked to ensure that every shop owner had a commercial license and lease. Here the municipal member chooses to subvert this obligation. He bargains with the shop owners living in his district, and their “donations” are used to conduct small but visible urban development projects. Likewise, another member explained to me that she voluntarily underestimated the number of commercial leases, and then ask to shop owners to pay off the difference in the form of a “donation” to the municipality. Informal and illegal agreements thus result in public and visible projects, turned into political legitimacy resources for the municipal officials. However, because of this permanent bargaining, their position as elected officials appears deeply weakened, and their clientelist relationships are largely reconfigured. While local politicians traditionally hold a secure ‘patron’ position,[18] in Zarqa, the shrinking of public resources makes them dependent on their constituents. Their governing capacity then depends on their ability to insert themselves into local economic networks as well as to always renegotiate the frontier between official and unofficial politics.

[1] Data collected during fieldwork in January 2019.

[2] Betty A. Anderson, Nationalist Voices in Jordan: The Street and the State (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005); Tariq Tell, The Social and Economic Origins of Monarchy in Jordan (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

[3] Myriam Ababsa, “Jordanie: la décentralisation par décision centralisée et la démocratie par volonté royale,” in Local Governments and Public Goods: Assessing Decentralization in the Arab World, edited by Harb, Mona, Atallah, Sami (Beirut: LCPS, 2015), 139–80.

[4] Janine A. Clark, Local Politics in Jordan and Morocco: Strategies of Centralisation and Decentralization (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 12.

[5] Jillian Schwedler, Faith in Moderation: Islamist Parties in Jordan and Yemen, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[6] Amman municipality is not taken into account here. OECD, “Towards a New Partnership with Citizens: Jordan’s Decentralization Reform,” 2017, 107.

[7] Ababsa, 167.

[8] The distinction between Transjordanians and Jordanians of Palestine origin is a frequently invoked framework for explaining loyalist-opposition divisions within the population of Jordan. However, it is worth noting that Transjordanians should not be considered as unconditional supporters of the government or regime. Some of the strongest forms of opposition and critique vis-à-vis the political system have historically come from those sectors of the population identified as Transjordanian.

[9] Ababsa, 168.

[10] Clark, 183.

[11] Centre for Strategic Studies, “The Municipalities,” 2004, 6.

[12] Electoral data can be found on the website of the Independent Election Commission: https://iec.jo/en.

[13] Jean-Louis Briquet and Frédéric Sawicki, Le clientélisme politique dans les sociétés contemporaines (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1998), 7–37.

[14] Clarence Stone, “Urban Regime and the Capacity to Govern: A Political Economy Approach,” Journal of Urban Affairs 15 (1993), 1–28.

[15] Interview conducted in January 2019.

[16] Interview conducted in January 2019.

[17] Interview conducted in February 2019.

[18] Briquet and Sawicki.