[A monthly curation by Maryam al-Khasawneh and Tanya Habjouqa, the Intimate Histories series explores personal archives that situate individuals within broader dynamics and collectives. Exploring the past through such archives, whether family, individual or otherwise publicly inaccessible archives, has the power to evoke a memory or inspire a conversation that can stretch beyond one’s own immediate parameters. These intimate visual records stand as a challenge to incessant pressures to reduce history into a linear narrative or to reduce photo narratives into conventional twelve-picture photo essays.]

In this Intimate Histories series premiere, we offer an excerpt of a private conversation between Algerian photographer Lola Khalfa and Bahraini photographer Mariam Alarab, two Arab Documentary Photography Program (ADPP) photographers, who first met in Beirut back in August 2019. This conversation took place in June 2020.

Lola Khalfa initially came to ADPP with a project called “je t’aimehic” about her brother and the broader LGBTQ community in Algeria. In the process, she came to realize that she was actually “finding” her father. Jet’aimehic became “De l’eau”, a project that retraces a personal and painful part of the history of her family.

Mariam Alarab’s But Hope Is Born from the Suffering Womb is an on-going project that draws a portrait of the scattered pieces of a country in turmoil, it follows stories of Bahraini people as they attempt to recover from the trauma of loss and violence, of details that are lying low beneath the surface, yet in plain sight.

Throughout their conversation, we discover their shared personal histories. Their fathers were both engaged in politics in the 80s and 90s. Lola’s father Mohammad Khalfa was assassinated for his political engagement; his death masqueraded as a car crash. Mariam’s father Abdulamir Alarab died in a car crash that left many questions unanswered, including speculation it was tied to his political activism. Sandwiched between these events were the effects of the Iranian revolution of 1979 and the Algerian Civil War (1991-2002).

Interview between Lola and Mariam

Mariam: Hey Lola... missing you. With love from Bahrain. Where are you now?

Lola: Stuck in Paris since March because of COVID. I came here to digitize my father’s home movies, and I am still here waiting for the border to open because the Algerian government has stopped repatriation until, as our president declared last week, “God completely lifts the virus from our country.”

Mariam: Insane. I cannot believe the Beirut [ADPP] workshop was canceled. Everything is messed up. Our conversation really began in Beirut… you approached me after my presentation and said my father’s story was your father’s story.

Lola: On the surface, it was so obviously similar. We both lost our fathers in a car accident. They were both politically engaged.

Mariam: Yeah. You were outside… and you asked me about my father.

He lived in exile for twenty years and we came back to Bahrain in 2001. In 2007, I lost my father in a car accident. At that time, I was so naive about the political situation in Bahrain. It was a car accident that some suspect was related to his activism. My father tried to keep me and my sisters away from politics, and he wanted us to focus on our education, but his death raised many questions for me. I started to collect his pictures and whatever else he had left. I found letters and writings from him which drove me to reflect on our situation and the conditions of our life at the moment. But you know, we cannot really know the truth.

Lola… how do you even begin making sense of your story?

Lola: In 2002, an assassination disguised as a car accident took my father’s life. As a sixteen-year-old school girl at the time, I suspected nothing. When I came home in the evening and saw the people outside our house, I remember seeing the bruised face of my Uncle Lahlouh—one of the few friends of my father who was able to survive the decade. It was then that I understood that something had happened to my father. Out of a desire to protect us, my paternal grandmother and father’s cousins did not want to list the real cause of his death. Years later, when my mother regained her senses, she slowly resumed her life and revealed the truth in glimpses.

I think somewhere inside I knew it all along… As I began unraveling his story, our story… I found archives detailing twenty years of my father’s political activity. I now understand that could not have left all that effort aside, not even for his family…. There was always a small part of me that resented losing my father because of his political activity. My father died at the age of forty-seven, keeping this part of his life secret from his sixteen-year-old daughter to protect her… I came to ADPP with a project called “je t’aimehic” about the LGBTQ community and my brother. I slowly understood that I was finding our father in my documentation.

Portrait of my brother Tarek, removing makeup after a party night with friends. © Lola Khalfa.

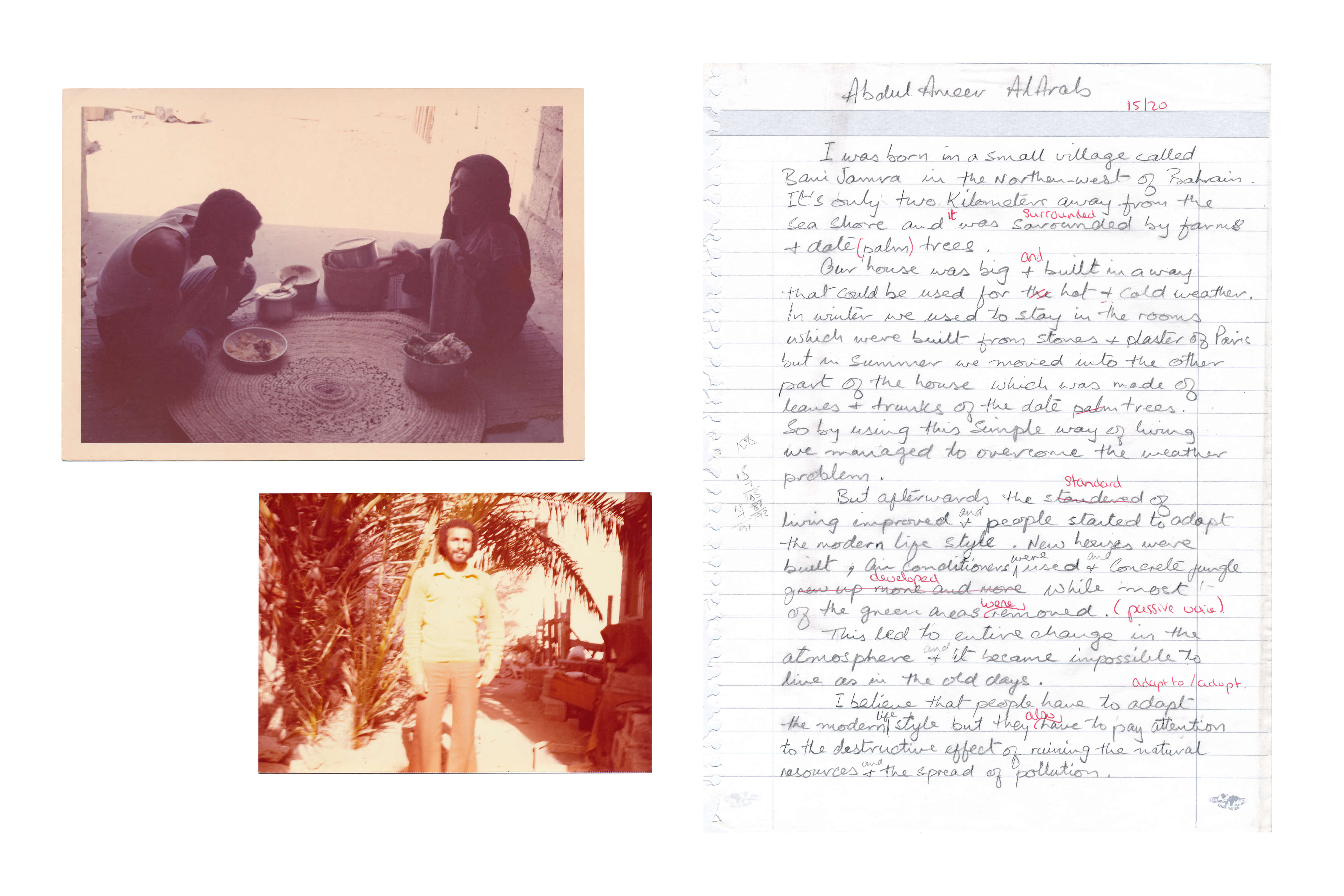

Mariam: For me, I knew from the beginning this was about my father. After he died, I somehow wanted to know him more through his archive. So I collected his documents, everything I could find: photos, letters, papers related to his job. For a very long time, I was somehow living through his archive. His writings and letters are the clues I am now following.

Handwritten article by my father describing his village “Bani Jamrah,” found in his English class notebook from his time in exile. © Alarab Family Archive.

Lola: I came to ADPP with a story that I thought did not reference politics… but in both of our projects you can see the heavy weight of the intersection between political narration and our father’s memory. Yet at the same time, I resent how everything from our region must always be reduced through the lens of politics. Even our personal family histories.

Mariam: I wanted to ask you. I know that when you came to Beirut you had this initial idea to tell a story about the LGBTQ community in Algeria, but then it evolved to be your brother’s story. I know that your project is still a work in progress, but you had articulated the story of your brother because you discovered another layer to that story, which is related to your family history and your father's story. Can you take me through the process of what happened?

Lola: When I came to Beirut [for ADPP], I wanted to talk about the LGBTQ community of Algeria, and the initial aim was to understand that community—to give them a voice in Algeria. I was not ready to explain that the real goal was to explore my brother’s pansexuality. After talking to my mentors (Tanya Habjouqa and Peter Van Agmael), they asked me for more of the personal, to dig deeper into why I wanted to tell the story of the LGBTQ when I was not a part of it. We began to discuss my family, and it was all related to my brother, my father, and that family story. I realized I was angry with my brother. But not for his sexuality. My father and his friends fought as best as they could, while trying to maintain a "normal" life balancing family and their political protest during the civil war of the 1990s. By ignoring the executioners, it was their way of combating them. So when my father felt that some of my then fourteen-year-old brother’s friends were trying to take him under their wings with a violent utopia dressed in religious speeches, my father decided to send him to live and study with another family. My father died without reconciling with my brother.

I wanted to understand my brother's story, to understand why he’d had “extremist” friends at this time? So the project began to be constructed around the family story, and what “terrorism” did to our family and all the choices we made after that period.

Mariam: Who were those terrorists?

Lola: In 1990-91 Algeria, the people elected the FIS, an Islamist party, first in the local elections and then in the first round of parliamentary elections. And after that, the [FLN-controlled] government canceled the parliamentary elections to prevent a total FIS victory. A civil war erupted between the government and several Islamists groups, not all of whom agreed or collaborated with one another. Then the government brought them back to power again. and this marked the beginning of what was called the ‘black decade’, so Algeria became that “violent” country. After a series of arrests and the dissolution of the FIS, many Islamists declared armed struggle—initially targeting the army and the police. Some groups quickly began to attack civilians, mainly targeting intellectuals, artists, and politically engaged people.

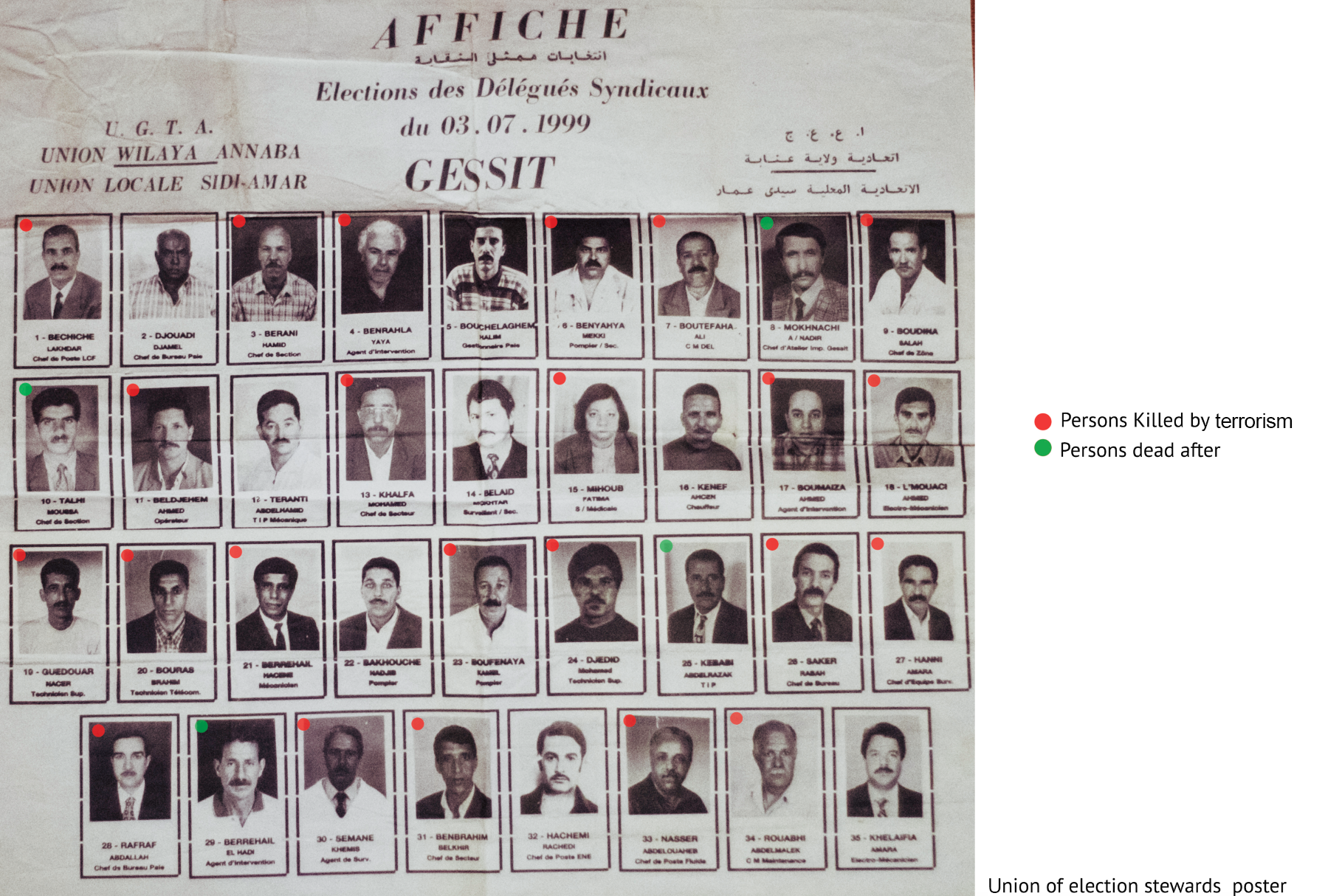

My family was targeted because my mother did not wear a hijab. Both of my parents were involved in various causes: women's rights, the Communist Party, and were active members of the Parti des Travailleurs Algériens Indépendants (the Algerian Independence Workers’ Party). She was a French-language teacher in that period and he was was head of the transport department at “el Hadjar,” the largest iron production company in Africa at the time. Most of the members of the party lost their lives because of their political engagement.

Poster of Parti Indépendant des Travailleurs Algériens. © Lola Khalfa.

Mariam: When you came back from Beirut you discovered your father’s huge archive, like I did mine. I think it had photos and documents, and you showed it to me. What did you do with it when you first found it? How did you work with it?

Lola: It came very late in the project because I did not want to talk about my father and his story. It was almost in the last month that I finally said, OK. Everything was turning and shifting to my father's story. So I told myself, “you have no other choice, you have to treat it properly and try to understand it.” In the last month, I felt I had to talk to my mother to try to understand my father's choices. My mother was very excited. She told me that she had always wanted me to work on the archive, but thought I was not ready. After I approached her she said, “come, I am going to show you something.” We had this huge drawer there in my father's room, and we just moved it to the living room and began to go through it.

And then, it began to make sense. In the archives, I saw all of his engagements, all of the things that he did during that period. That made me understand his engagements better. He could not just say, “OK, I am sick of it, I am just going to leave all of that,” after twenty years of political activism—you know.

Mariam: The archive, was it a collection of photos, letters, or documents? What was it?

Lola: Documents about his political party, the Communist Party “Parti des travailleurs Algeriens Independants”. Newspaper columns that my father wrote every month. There were articles about feminism and others about friends who were killed. There were posters of the party. It was a lot, but the thing is, I saw that he didn't have personal writings. There were always many voices in every single document, not just my father's voice. So until today, I do not know what he was really thinking. He did not put his interior thoughts on a single paper or document. So I tried to understand him by watching and reading all the newspapers.

Mariam: You know, my father's archives are kind of the same. They were mostly about his job in the telecommunications company. And the other part is all the papers and speeches, as well as analyses of different current events. There were also newsletters that he was writing. So, I think his archive, in a way, helped me understand his perspective of politics in the country. I had more hunger to know him better. He left too soon. I was only nineteen and I think it is the age where you start to somehow move into adulthood and then maturity. You start shaping your personality and thinking differently. I was always asking my father's archive to give me more. I did the same thing as you: I was trying to organize the documents into a timeline to understand my father's life, how it went by—his educational certificates and then the articles he was collecting. I was looking at the articles and his writings, always thinking, what does he think about a specific topic? And why did he do this or that? Why was he pushing for more rights for those who came back from exile to Bahrain in 2001?

Lola: Can you tell me more about your father’s political activity?

Mariam: In the early 1970s, at a particularly important moment of the nationalist and leftist struggle, my father Abdulamir Alarab participated in activities calling for the defense of citizens’ rights and demanding political reforms in the country. He continued to fight for these causes as he joined an Islamist movement. The emergence of Islamist political movements across the region during that time cast a shadow over Bahrain... In 1981, my father left Bahrain due to an arrest campaign against political activists following an alleged coup attempt. From Syria, where he had relocated, he covered the nineteenth uprising in Bahrain through a newsletter that he wrote.

I was born in exile and I spent my early childhood in Syria, on the outskirts of Damascus. I knew that I was from a country that I had never seen called Bahrain. So I was so free to create an imaginary picture of what Bahrain looked like. The area where we lived was, I guess, the intersection of people who shared certain struggles: Iraqis escaping the oppression of Sadam Hussein, Hazara Afghanis escaping discrimination, Syrians from the occupied Jawlan territories (Golan Heights), and/or people from other parts of Syria seeking better living conditions. Since life, in general, was not easy in Syria, this made me feel that we were not alone.

The year 2000 is one that is stamped in the memory of my thirteen-year-old self. King Hamad bin Isa ascended the throne in Bahrain following the death of his father Isa bin Salman. A new era had allegedly been ushered, closing off a long period of political tension that had peaked during the 1990s and Shaikh Hamad announced a pardon of all arrested or convicted political prisoners. The opposition that was working in exile returned to Bahrain. My father resumed his work through the Islamic Action Society (Amal), which was founded in 2001.

Photo captured at the entrance of Bani Jamrah village. Photo by Hussain Lari in 2001, published in Al-Arabi magazine, issue 516. On the right, a photo of my father with the Arabic text stating, “Abdulameer Alarab: 20 years of exile and fighting for justice.” On the left, a photo of Abdulameer Al-Jamri, a spiritual leader and member of Bahrain’s 1973 Parliament. Next to him is his son Mansoor Aljamri, who came back from the United Kingdom after the 2001 reforms in Bahrain, and served as a founding member and editor in chief of Alwasat independent newspaper. The yellow banner in the middle says, “Bani Jamrah village welcomes back the son of the homeland.”

Lola: Where did your father get this strength from?

Mariam: People would always tell him that he reminded them of my great grandfather, as both of them sacrificed their lives fighting injustice. Shaikh Abdulla Alarab, my great grandfather, is very much alive in the collective memory of many Bahrainis. He was a poet and respected scholar of his time. His body was discovered, with multiple knife wounds, along with another friend of his—a few kilometers from his own village Bani Jamrah in 1923. This was after he petitioned Major Clive Kirkpatrick Daly, the British Political Agent, demanding the British to stop the attacks against Bahraini villagers and repeal a law called “al-Sukhra”—a type of forced labor practice. My great grandfather was killed after submitting the petition, and so many people have linked his murder to this particular event. My grandfather became an orphan at the age of 6. My father never met my great grandfather, but I guess the legacy that he left was something to aspire towards.

Lola, do you think your understanding of Algeria changed after working with your father's archive? Like, the way you look at Algeria? Especially because the country is passing through a very special time at the moment—people are on the streets. The Arab region in the last ten years has been passing through a very special time.

Lola: First, my mother continued her political commitment after my father's death. I was always with her. She was so naive. I constantly felt that politics was just about words. Nothing really ever changed. Before going through the archives, I would say that nothing was going to change if we did not change minds. If we just count on politics, nothing will change. We have to educate people. We have to put the real energy into that. After seeing my father's archive, I felt that I was right. Nothing actually changed. There were a lot of people, some say ninety percent of artists and activists of Algeria, that were killed during the dark decade. So I said, okay, it is not working. After seeing the archive, and after living the Algerian uprising last year—marches and protests—I saw the same thing happen again. So nothing changed for me, we have to focus on education first and politics will follow.

Mariam: So, you know, there is a reason you decided to take the story through this path in the first place. You wanted to talk about the LGBTQ community. Then it took some courage for you to shift it toward this broader narrative, or to add more layers to your story, the story of your brother, and the story of your father and your mother. It is as much your story as well. So, what are you trying to tell through your story and why?

Lola: It is very simple. I am just trying to give that little girl the chance to express herself. To try to take some memories of that little girl and tell her, “it's okay,” and to find answers for myself. I am just trying to understand and talk to that little girl and tell her why everything happened. That makes me better understand my father's choices. If I can say one thing about the process of making this project, it would be that it was a great form of therapy to finally reach forgiveness. And that's why life is the way it is. What about you? Has your project served as a séance to understand your father?

A moment at night, my brother Tarek, my mother, and I have this ritual of leaning on my mom’s bed and talking or just being there together. © Lola Khalfa.

Mariam: I think it started with me trying to understand. In the beginning, I was seeking to understand my father and then it turned into me trying to understand my country as well, politically and socially. I guess, the way I tackled the project, mixing between exploring my father's archive and exploring my own country through photography, has helped me in a way—to look at the bigger picture somehow, in a metaphysical way, and to bring in some direct and in-direct images. Because I think this is my continuous need: to understand and explain things around me.

Lola: You mentioned the bigger picture, what do you mean by that?

Mariam: I mean the bigger picture of the story of my country. I am trying to depict a portrait of my country the way that I see it, through my personal history. Of course, photography has helped me observe more closely or to get more acquainted with my community’s stories. But in a way, I had a big fear of being honest. For a while, it was really difficult for me to put this fear aside, for many reasons: mainly not really knowing if I would be able to say everything I wanted to.

Walled and privatized reclaimed land on the coast of Hamala village. Many of Bahrain’s public beaches were privatized, leaving a little room for people to escape to public spaces. © Hussain Almosawi & Mariam Alarab

Lola: Exactly. I was very lost. When I came to Paris in March 2020, I think I was very lost. I said, OK, what am I going to do with all of these archives? Or with my mother's stories? And one day I woke up, I took my coffee and told myself to be honest, be myself. Talk to that girl! I swear I was talking to myself as a child. It helped me a lot. When you bring up those moments of that child, you have to be honest and that really helped to structure and tell the story.

Mariam: You mentioned before that you were looking for answers, did the project help you find these answers? If so, what were they?

Lola: I decided to talk to that little girl and try to take a step back and try to see my father as a person with his own opinions, his own fight, you know, his own experiences in life—not just as a father who had to protect his children all the time. I now imagine how I would react if someone told me to stop my photography, or to not to cover sensitive topics because it's dangerous. So I try to compare it. And that has helped me understand his opinions better. It helped me to not be that little selfish girl who thinks just about herself not being with her father. My mother once told me, “art is your way of showing your engagement and trying to make a change.” But for me it’s like intuition, you know, I am moved by things that disturb me in society. I go and I try to talk about it with my photography. I think we have to do our work and be honest with ourselves and with our commitments. We have to try to not expect something from the topics we deal with/explore. It's my way of protecting myself. It's something that I tell myself, in order to not be disappointed.

Mariam: I think it is the experience of the Arab youth that went through many disappointments. It is a way to cope. But at the same time, you know, part of the reason for doing the work I do is me getting tired of seeing how our narratives are manipulated by the media. For me at least, I felt that I needed to tell my own story in the most honest way I could tell it.

Lola: OK, it is like saying you can take a lot from me, but you are not going to take my story.