“Are you a family?” the young prison guard asked my mother and me as we were sitting behind the double bullet-proof glass separating us from my father and brother in Ramon prison’s visiting room. It was the first time the four of us were together since the arrest of my father, Abdul-Razeq Farraj, in September 2019, and the subsequent arrest of my brother, Wadi’, in November.[1] For this young guard, the sight of an entire family separated behind the visiting room’s glass and fixed telephones was perhaps a rare occurrence: indeed, given our possession of a Jerusalem I.D. allowing us to travel inside historical Palestine, my mother and I are able to visit without the need to apply for permits. Numerous Palestinians my age are automatically denied prison visit permits and rarely—if ever—get to visit their family members. The guard’s reaction, however, is not the story here. The story is one about torture behind bars and ways in which the Israeli occupation has instrumentalized the COVID-19 pandemic so as to further entrench the systematic torture of Palestinian prisoners and their families.

The outsides of Ramon Prison in the Negev Desert. Photo by author.

Since its creation in 1948, Israel has used imprisonment as a central policy to subjugate Palestinians, punish them for their resistance, and thus dismantle and disrupt notions of a collective Palestinian national movement. Available figures attest to the enormity and centrality of imprisonment to the Israeli colonial project. As shown in the book Asra Bila Hirab, during the first year of the occupation’s violent existence in 1948, an estimated twelve thousand Palestinian and Arab prisoners were imprisoned in newly-created prisons and in sites previously used by the British colonial power. Additionally, the Palestinian Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association (Addameer) estimates the number of Palestinians imprisoned during the years 1967 and 2016 to be around 800,000 prisoners, amounting to twenty percent of the total Palestinian population. Currently, nearly 4,400 Palestinian political prisoners linger in Israeli prisons.

Torture has accompanied the Israeli carceral project since its inception with numerous reports and testimonies documenting the large-scale torture practiced against prisoners by the various Israeli armed and intelligence agencies.

Torture has accompanied the Israeli carceral project since its inception with numerous reports and testimonies documenting the large-scale torture practiced against prisoners by the various Israeli armed and intelligence agencies. Palestinian and Arab prisoners have long been subjected to methods of torture ranging from various physical and psychological methods to what Walid Daka, one of the longest-serving Palestinian political prisoners, describes in a text written and smuggled from prison[2] as a civilized and hidden mode of torture that turns prisoners’ “own senses and mind into tools of daily torture.”[3] Daka argues that policies and measures put in place by the Israeli Prison Service including isolating imprisoned political leaders, segregating prisoners along geographic considerations, and punishing prisoners’ collective gestures constitute part of an invisible mode of torture directed at reshaping prisoners’ minds and spirits, and towards redefining the Palestinian political imprisonment experience. While this article deals particularly with torture committed in interrogation rooms and during pandemic times, Daka’s text is important for thinking through broader manifestations of Israeli torture and how it is to be contextualized in the present carceral moment.

While torture has never left the Israeli carceral project, two moments came to define Israel’s relation to the torture of Palestinians in interrogation rooms. In 1987, an Israeli government-sanctioned commission headed by retired Supreme Court Justice Moshe Landau published a report which held that moderate and psychological pressure can be employed by interrogators to prevent terrorism. The report permitted the use of torture under the pretext of employing "moderate pressure" and kept secret the guidelines defining permissible and prohibited methods. Torture continued unabated following the publishing of the Landau commission’s report. In 1999, in response to claims made by a number of human rights organizations on behalf of tortured Palestinian prisoners, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled that the use of brutal or inhumane methods during interrogation was prohibited. In theory, the ruling forbade the use of a number of interrogation methods, including subjecting prisoners to painful waiting positions, shaking, excessive tightening of handcuffs, exposure to loud music, and sleep deprivation.

In practice, however, the High Court of Justice ruling had wrapped torture with a cloth of legality where it had in effect permitted the use of physical force in what is referred to as “ticking bomb” situations and left the question of legality for the legislative branch. The ruling invoked the “necessity defense” laid out in Israel’s penal code where, under certain conditions, interrogators who employ prohibited torture methods are absolved of criminal liability. The Court’s decision had, therefore, allowed Israeli officials to torture prisoners under the framework of exception while claiming that the occupation is law-abiding. The ruling created a situation where Palestinian claims of torture are rebuffed with usual statements of denial by the occupying authority, and with terms such as "special means," "moderate pressure" and "ticking bomb"; terms that quantify torture and in effect work towards providing a legal context for its use. Indeed, twenty years after the Court’s ruling, torture of Palestinian prisoners continues to be a systematic and wide-spread practice that enjoys the complicity of the Israeli judicial system, and of Israeli medical personnel.

The torture to which dozens of Palestinians were subjected during a large-scale arrest campaign that commenced at the end of August 2019 is a case in point attesting to the centrality of torture to the Israeli carceral project, and to Israel’s relentless attempts at providing a legal cover for the ongoing reality of torture behind bars. During this campaign, Israel subjected dozens of university students, human rights defenders, and political leaders to harsh and extremely violent interrogation methods in an attempt to extract confessions and break their spirits. The majority of the detainees were subjected to prolonged bans on lawyer visits, thus cutting them off entirely from their surroundings and denying them legal counsel during their interrogation at the hands of Israel’s intelligence agencies.

Testimonies collected by a number of human rights and prisoners’ support organizations from detainees arrested during that period describe the tactics employed by Israel’s intelligence agency “Shabak,” and the torture methods which were used in interrogation rooms. For months, Palestinian prisoners were subjected to a range of torture methods that included beatings; threats against family members; arrest of family members; pulling facial and scalp hair from the roots; kicks on the thighs; slaps; beatings; suffocation; and a number of stress positions including the banana position, shabeh[4] and the frog crouch. The case of Samir Arbid garnered heightened attention when he was rushed to the hospital in an unconscious state. He had fractures in his ribs and bruises all over his body following his first two days of brutal interrogation at al-Mascobiyaa center in Jerusalem. Samir’s interrogators received permission to employ "special means" during the interrogation.

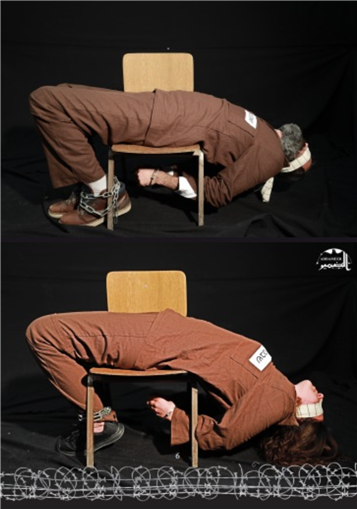

Addameer recently published a booklet documenting the torture that Palestinian prisoners had endured during this recent arrest campaign. Based on prisoners’ testimonies, the booklet recreates the stress positions and torture methods employed by the Shabak in its interrogation of Palestinian detainees. The pictures confirm what Palestinians have long been saying: torture has never stopped in interrogation rooms; it is a constituting element of the Israeli carceral project. The photos depict methods constituting cases that fit the definition of torture put forth in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Israel, however, continues to deny its use of torture against Palestinian detainees.

My father was one of the prisoners subjected to several of these torture methods last year. My mother and I were allowed to attend one of his court sessions following over a month of interrogation at al-Mascobiyya center during which he was subjected to a prolonged ban on lawyer visits. It was the first time we saw him and heard his voice since the beginning of the interrogation, albeit for a little less than two minutes as we were quickly kicked out of the courtroom. I clearly remember every detail of that day in November of last year: the drive to Ofer military court; the anticipation of his arrival in that small courtroom; his appearance and frail body; his barely audible voice; and the silence which dawned in the car as we left the military court towards our house. My father entered the courtroom barely able to walk; his body extremely tired and brutalized; his beard and hair with a length and greyness that we have never seen before. He immediately asked about the health of his sick mother who would later pass away without him being able to attend the funeral or say goodbye to her, and about my brother Wadi’ who was similarly being interrogated at the hands of the occupation’s intelligence personnel. His voice was shaky, barely audible, as if he had not spoken in years. He leaned to the "defendant" bench with his two hands as to gather strength for his tortured body, and as not to fall. The two minutes were over before we knew it.

These are glimpses of the torture that regularly takes place behind the closed doors of Israel’s interrogation rooms. In its interrogation of Palestinians, the occupation resorts to numerous methods in order to break the spirits and wills of detainees. Israeli torture, however, does not stop at the doors of interrogation rooms. It extends to every aspect of the prison experience. In fact, following decades of dealing with Palestinian political prisoners, the occupation has perfected a system of incarceration where policies are put in place to create states of ongoing subjugation of prisoners and their families. Palestinian prisoners are subject to systematic medical negligence, to denials of visits and communication with their families, to restrictions on access to education, and to painful journeys in transfer vehicles referred to in Arabic as the bosta. Prisoners, once done with the tormenting experience of interrogation, are once again subject to webs of policies and practices designed to further subjugate them and their families in what Walid Daka eloquently describes as processes of consciousness re-molding. As families would tell you during prison visits, “the occupation is creative when it comes to devising ways to humiliate us.”

The Pandemic Excuse for Torture

These carefully designed webs of torture that are always being developed are ever-clearer in ways in which the occupation has put the COVID-19 pandemic to use in an attempt to further subjugate prisoners and their families. Since the advent of the pandemic, the occupying authorities took no steps to release Palestinian prisoners and detainees nor did it put in place measures to protect them from the virus. Indeed, the occupying state continues to arrest Palestinians and subject them to interactions with prison guards and interrogators, many of whom were later diagnosed with the virus or sent to quarantine. Pointing to the blatant disregard for Palestinian lives (this disregard should not come as a surprise to the reader), the occupation’s Supreme Court rejected a petition demanding protection from the virus for Palestinian prisoners at Galboa’ prison and denied them the right to social distancing. The occupation’s prisons are breeding grounds for the virus given the dismal detention conditions, overcrowding, lack of ventilation, recent restrictions on purchases from the prison canteen, and the unavailability of sanitary and hygiene products.

Notably, the occupying authorities refused to release Kamal Abu Waer who was diagnosed with, and later recovered from, the virus and who is already suffering from throat cancer and with a deteriorating health condition. Medical negligence is the norm behind the occupation’s bars; before and after the advent of the pandemic. Recently, Daoud al-Khatib, three months away from the end of his eighteen-year sentence, died of a heart attack in Ofer prison. Currently, it has been reported that dozens of Palestinian prisoners have been diagnosed with the virus in Ofer prison alongside ongoing raids against Palestinians in that same prison.

On 5 April 2020, the military commander issued an order regarding “conducting the court sessions using technological means.” This order dictates that court sessions should be conducted through a device giving both visual and audio live streaming, and to resort to audio if visual streaming was deemed not possible. Only in specific cases are detainees physically brought to the court. At first sight, this order might appear in line with restrictions put in place to minimize interactions between guards and prisoners, and to protect against the virus. However, the occupying authorities have used these changes in ways courts are conducted to further deny, and restrict, communication between prisoners and their families. The small computer through which prisoners appear is stationed in close proximity to the judge, and in many cases, families are not allowed to approach the computer and remain in distance attempting to hear and see their loved ones. The audio is barely audible amidst the chaos of military courts, and the image is extremely distant. This is particularly tormenting for families denied prison visits and for whom attending court sessions is the sole mean of communication with loved ones.

Additionally, while the occupying authorities had first put in place a complete ban on prison visits, it recently allowed visits for solely two members of each prisoners’ families in strict conditions designed to further harass those making the arduous journey to prisons.[5] It had also reduced the number of allowed visits—for those who receive permits, of course —to six times a year: once every two months. The new measures related to court conduct and prison visits constitute a continuation of policies put in place to further restrict prison visits and communication with prisoners. While these measures might appear as an attempt to protect against the virus, in reality, they constitute a change of policies certainly to become the norm where prisoners are further cut apart from their families, and where communication is further curbed.

In its broader attempt to subjugate Palestinians, the Israeli occupation has relentlessly been working and devising means to subjugate the Palestinian prisoners’ population. Variants of its modes of torture, both within and outside interrogation rooms, is an attestation not solely to the centrality of torture and its reconfigurations to the carceral project but also to the never-ending Israeli occupation’s legal work to dress torture in a garb of legality. Within Israel’s meticulously constructed reality of legalized violence, torture is denied while simultaneously presented as an exception to the norm and as a last resort in the face of never-ending threats. The COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to the Israeli occupation to continue its attack against Palestinian prisoners through blatant disregard for their lives and health, and through devising new measures—entrenched in military orders and new forms of conduct—that would further the systematic torture of prisoners. Torture behind bars is therefore not solely to be found in interrogation rooms but extends to every aspect of the prison experience. It is a constitutive element of the occupation’s carceral project and its manifestations outside prison bars. As Issa Qaraqi’, the former Palestinian minister of prisoners affairs, recently told me, “the occupation had perfected its unique form of modern torture.”

Despite these intricate webs of torture, certain voices continue to challenge the occupation regime and its attack not solely against the body but the mind and soul of imprisoned Palestinians. In a letter smuggled from his prison cell months after a brutal torture to which he was subjected, one from which he is still recovering, a friend defyingly wrote, “How do I conclude my letter? After years of imprisonment and resistance, and following the latest round of successes, failures, and defeats, now I can start again, once again, from the beginning.” Additionally, as these words are being written, Maher al-Akhras has entered his ninetieth day on a hunger strike demanding his immediate release and an end to Israel’s resort to administrative detention; a policy allowing the occupation to arrest Palestinians without charge or trial for prolonged periods of time under the—unsubstantiated and always present—pretext that the state’s security is at risk.

[1] Wadi’ was released in October 2020 after serving an eleven-month prison sentence.

[2] Palestinian political prisoners have long been engaged in processes of writing from prison contributing to what is referred to as "prison literature." Given the restrictions Israel places on communication with the outside world, prisoners’ writings are smuggled through various means, and later transcribed and published.

[3] Walid Daka, “Consciousness Molded or the Re-identification of Torture,” Threat: Palestinian Political Prisoners in Israel, edited by Abeer Baker and Anat Matar, (London: Pluto Press, 2011), 235.

[4] This stress position involves a combination of methods where detainees’ legs and hands are tied to a small chair usually angled to slant forward. The position is accompanied by sleep deprivation and ongoing infliction of pain.

[5] These visits were halted when Israel commenced its second lockdown on 18 September 2020. Families were informed by the International Committee of the Red Cross that prison visits would resume beginning from the end of October 2020.