[Read Part 1 of this article here.]

From Intellectuals to Audiences: Youth and Their Relationship to the Recent Past

It was puzzling that Laroui’s ideas did not occupy a more central role in the national conversation on reform and the political models since 2011, despite his “return” in the public sphere. The answer to this puzzle, according to the writer and journalist Abdellah Tourabi, is that “people talk more about Laroui than they read him.” On the one hand, he is “fetishized, as part of the 1960-70s generation, adding to that mythology of a golden age.” On the other hand, his intellectual project sits on a shelf and is seldom revisited for the needs of the present. The Moroccan historian Mostafa Bouaziz has recently spoken out for the need to read Laroui again, because of the way he places current questions in their proper historical context. For Bouaziz, the burning questions today relate to citizenship, national language and gender equality, and Laroui offers a way to counter opportunistic demagogy by putting these questions in a larger historical context.[1] As such, Bouaziz points to the Moroccan intelligentsia’s responsibility to be mediators between the texts and the broader public.

In addition, Tourabi notes that the older intellectual figures might not be suited for the new public sphere. Could they adapt to the virtual space, widely touted in 2011 as a way to circumvent political closure and reach new audiences? Tourabi contrasts the old forms with the current screen culture and short attention spans. He foresees difficulties for members of this old generations to adapt to this evolving ecosystem: “this explains why they appear bothered, we don’t see them often, and when they try to adapt, it appears awkwardly done.” It is unlikely to see this change happen, and maybe it is wrong to expect it.[2]

The junction between old discourses and new communication has come from elsewhere. One of the most surprising developments I witnessed was how Laroui’s intellectual project was being revived by a younger generation of Moroccans whose encounter with Laroui’s intellectual project was not mediated by their predecessor’s complicated rapport with this “missing father figure” after the radical 1970s, but rather they formed their views in the early 2000s.

Shortly after Muhammad VI came to power, the country appeared on course to make a democratic transition. The government of alternance brought the socialist party and Abderrahman al-Youssoufi to the government, old political opponents returned from exile, and symbols of the old regime such as the powerful Driss Basri were dismissed. [3] I spoke to two university lecturers, who were students in those years, who read his interventions as a call to the monarchy to reform and adopt constitutionalism. Salim Hmimnat, now a political scientist in Rabat, was a university student at the Muhammad V University a few years after Laroui’s retirement, and acquired several of his books for his work on Moroccan history. He also attended several round tables where Laroui spoke, including at the Bouabid Foundation, which forces us to revise the claim that he “returned” after 2011.

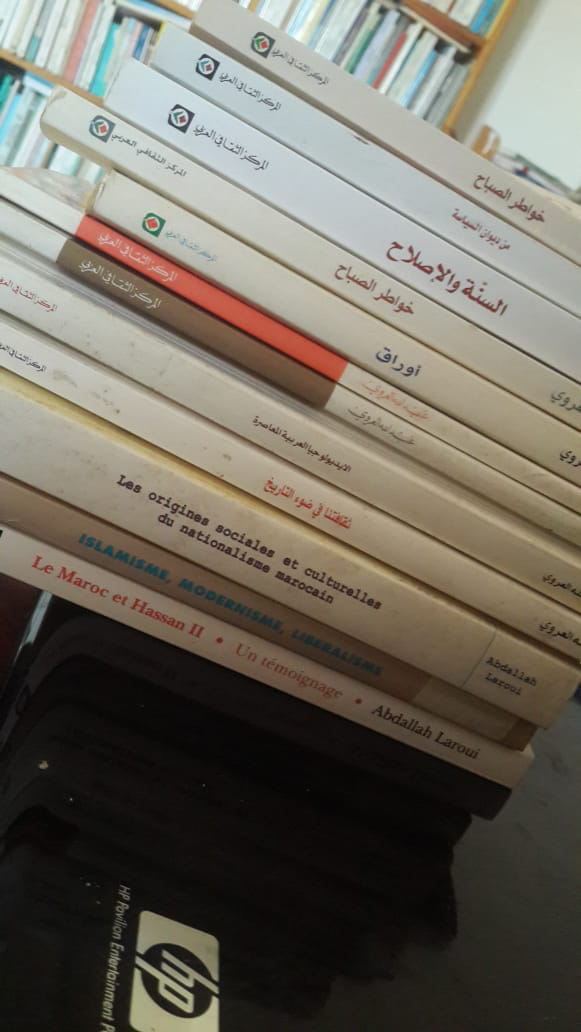

Picture shared by Salim Hmimnat in July 2020.

For Brahim Aït Izzy, a university lecturer in Marrakesh, his political posture after 2011 was consistent with his call for state-led political reform that he had been writing about for the past two decades: “he sent coded messages through his work,” which became clearer in recent years, Ait Izzy clarifies. This was clear to him in 2012 when Laroui released his translation of French philosopher Montesquieu in Arabic.[4] He began this work years before 2011 and it was his way of warning the Moroccan deep state, the Makhzen, against the risks of mixing of politics and economic interests. This later emerged as a main demand of the 20 February movement, yet the message did not seem to reach the authorities in the Palace. In 2015, Laroui released the latest volume of his memoirs, khawatir al-sabah covering the period from 1999 to 2007. It contained several entries where he lamented the lack of structural change and the resilience of tradition over reform, thus nullifying the ability of the socialist and the alternance to steer the country to new horizons. The other books he has since released can also be read under similar angles, including his translation Ibn Khaldun. Raison et déraison ou Une réponse satisfaisante à des questions embarrassantes (2019), or the translated and republished Sunnah wa al-Islah (2019), after the Islamist leader Abdelilah Benkirane was edged out of power.

This revival has also connected the virtual and physical spaces together. It coalesced around constructive initiatives such as the organization of reading and discussion groups. In January 2018, a cluster of young academics set up a discussion group from Marrakesh under the aegis of MADA, the centre for research and studies in the humanities, including Brahim Aït Izzy, to shed light on several Moroccan intellectual projects and discuss Laroui’s latest book Istibana (acknowledgement) on the fate of Moroccan nationalism. Similar initiatives were led by Maghareb, the centre for humanist studies and their cycle of thought with the philosopher Abdurrahman Taha, or Mominoun bila hudoud.[5] For now, these groups are still at the stage of discovering Laroui’s work rather than reinventing and repurposing it in the light of the experience of Morocco in the 2010s and 2020s.

There are signs that this relationship with younger readers works better than his engagements with the older Moroccan intelligentsia. Laroui sent a voice message to the conference celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of L’idéologie Arabe contemporaine, but he came in person to give the inaugural lecture of the Ben M’sik Faculty, at the Hassan II University in Casablanca, titled “Historian and Judge” in October 2012. At another sell-out event in 2018, he was patient with the press, with microphones shoved in his face, he recast this event as a celebration of a generation and its remarkable production rather than on himself.[6]

Brahim Aït Izzy remembers how, after coming out of that talk at the National Library, Laroui walked with a group of students chatting eagerly for a long while and keen to continue engaging with them. For anyone who has climbed the stairs from the National Library leading to the humanities faculty and the National Archives, this is not a mean feat especially on a sunny day in late April. Laroui, now aged eighty-seven, did not seem too bothered. (The picture was shared by Brahim Aït Izzy on his social media account on 21 April 2019).[7]

The Sheikh Zayed award for “Personality of the Year” made headlines in Morocco and the Arab world in 2017. It was a point of pride for the country as a whole, more used to being neglected by the Arab core. However, the more significant landmark was the opening of a chair in his name at the Humanities faculty of the Muhammad V University in Rabat in January 2020. The event was co-organized with the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, and the event had all the pomp reserved for foreign dignitaries. In the recently refurbished main lecture hall in Rabat, cameras flashed incessantly, the national media’s cameras lined up, in a display that would cause envy to government ministers. Laroui appeared at ease on this occasion, while crowded on the stage by university officials keen to bask in his reflected glory. Such events rarely escape this type of pageantry.

The more interesting sight was not on the stage but rather in the audience.

The lecture hall was jam-packed. Attendees arrived early to secure a seat and many had to sit on the stage itself, giving different energy to what is usually a stiff and pompous affair. The public heard Laroui list what he saw as the crucial questions in urgent need of attention in today’s Morocco: state reform, patriotism and citizenship, and the link between illiteracy and the digital sphere. Here again, he underlined the urgency of addressing education and culture. The public listened intently. Perhaps, now his message would come across.

These events from 2011 to 2020 offer a neat narrative of a great intellectual of the past making a long-awaited return. He went from a once-neglected figure to being a celebrated public intellectual thanks to the reopening of the Moroccan public sphere following the Arab Spring. However, this simplistic reading leaves out several other sub-plots. It was revealing of changing attitudes toward the recent past in Morocco, especially among the new generation.

On social media, Laroui’s 2013 television debate on education reform sparked a spike in interest. Shortly after, an old clip his 2000 participation in the 2M programme fi al-wajiha resurfaced and was widely shared. He spoke with the legendary journalist Malika Malak and several Moroccan intellectuals in an insightful exchange on political transition or education reform.[8] In my conversations with several MA or PhD students in Rabat and Casablanca, there emerged a clear link between these clips and their decision to dig deeper and learn about this figure, whom they had read or heard about in passing. These interlocutors were not the political activists of the 20 February movement but rather the future members of the cultural field who looked to Laroui was a lingering trace of an unexamined past.

The 1960s and 1970s occupy a complicated history in Morocco. On the one hand, it represents the “years of lead” or sanawat al-rasas during which political opponents were arrested, disappeared, and tortured by the regime. On the other hand, it represents a cultural golden age, of dynamic university campuses and radical imaginations of independence. This youth engagement with Laroui is a testament to a new approach to the recent past: curious, participative, committed, but also sometimes performative rather than substantial. I attended several events that resonated with the same drive to celebrate and honour past thinkers and Morocco’s intellectual heritage: from Fadma Aït Mous and Driss Ksikes’s book launch at Rabat’s Kalila wa Dimna book store for their volume Le metier d’intellectuel in April 2014[9] to the events celebrating Souffles/Anfass at the National Library or commemorating the life and work of Fatema Mernissi at the Villa des Arts in 2016, after her passing.[10] At each stage, one could see a growing group of university students in the room, standing on the sides but listening intently, illustrating a growing thirst to understand the country’s recent past from a generation that not just learning about its existence, but starting to realize its significance. Through these acts and social practices, they have been giving substance to the call to open up the recent Moroccan past, as called for by the country’s experience of transitional justice and truth commissions. In 2004, the Instance Equité et Réconciliation who recommended making official archives accessible and encouraging new forms of historical writing. Besides the establishment of official historiography, this experience has sparked other and original forms of historical revisionism, from the 2016 protests in al-Hoceima that reveal the intertwined nature of memory, history and regional marginalization, to the constitution of “other-archives” in prison testimony literature as argued by Brahim el Guabli.[11] Those I spoke to ended up attending the January 2020 lecture in person or followed it live on social media. I suggest that we see this act as constituting of a new historiography, insofar as it reveals a conscious strategy to consume specific cultural contact that impact the mnemonic field that will have long repercussions.

The story of Laroui’s revival invites us to continue thinking about Moroccans’ changing relationship to the recent past. His “return” may not be one in the conventional sense, but his increasing presence in the Moroccan public sphere has amplified a growing interest in the legacy of the radical sixties and seventies, a public sphere that began extending into the virtual space, and the sheer wealth of his philosophical insights on Arab modernity. There exists a story of history, memory, and inter-generational remembrance. Laroui’s omission in the new generation’s cultural baggage passed on from the previous generation was a glaring aberration. It was as glaring as the omission of the Moroccan radical past, largely relegated from view for the current generation, until its slow revival in recent years. The current generation that will populate the Moroccan intellectual and cultural field are already placing themselves in a position to rewrite the country’s history.

[1] al-Raji, “Laroui invites us to revisit the division of heritage and the obligation of writing wills” Hespress.com (18 January 2018). Link online: https://m.hespress.com/societe/378526.html?fbclid=IwAR1A5VnE0_NQoKVeA5zy2Dr7ODtZEn6HHCPRLhZw33IGmZd5XjGXutsPueg

[2] Kassab, “The Arab Quest for Freedom and Dignity: Have Arab Thinkers Been Part of It?” META 1 (2013), 26-34; Kassab, “Critics and Rebels: Older Arab Intellectuals Reflect on the Uprisings” BJMES 41.1 (2014), 8-27.

[3] Miller, History of Morocco 206-7.

[4] Muntiskiou, ta’amulāt fī tārīkh al-rūmān. ’asbāb al-nuhūḍ wa al-ʾinḥṭtāṭ. Translated from French to Arabic (Al-Markaz al-thaqāfī al-ʿarabī, 2012).

[6] “Al-‘arwi yadhhur ba‘ad ghiyab tawil: ’istawfaitu mashrou’i” Febryaer TV (18 January 2018).

[10] Lyndsey, “A long-shuttered Moroccan magazine still wields powerful influence” al-Fanar Media (19 April 2016). Link: https://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2016/04/a-long-shuttered-moroccan-magazine-still-wields-powerful-influence/

[11] Miller, “Why history matters in post-2011 Morocco” Jadaliyya.com (30 November 2016). Link: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/33789); El Guabli, “Other-Archives: Literature Rewrites the Nation in Post-1956 Morocco” Doctoral Thesis Princeton University, 2018.