[This article is part of a dossier on Tankra Tamazight, Amazigh Revival, and Indigeneity in North Africa, edited by Brahim El Guabli. To read other articles in this dossier, read the introduction here.]

Ancient historians have frequently borne witness to the Amazigh people’s abundant narrative tradition, passed down orally through the generations up to the modern era, when it was virtually absorbed by modern means of communication such as school, radio, and especially television, which invaded Amazigh culture with the allure of globalism.[1] Television in particular invaded Amazigh culture and made Amazigh speakers feel backward and culturally stagnant, resulting in a gradual abandonment of this tradition. Thus, an ancient Amazigh narrative tradition was gradually obliterated and now risks extinction. What remains of this tradition is simply what lives in the memory of the elders, especially those who absorbed this tradition at an early age, throughout the Amazigh territories. Even this last bastion will vanish if it is not preserved.

Driven by obvious colonial motives, the European colonizers who conquered North Africa between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, collected and recorded parts of this tradition,[2] but despite those motives they did Tamazight (Amazigh language) a favor by safeguarding part of that tradition which otherwise could have disappeared. After having been exposed to the literature of other nations, subsequent generations of Imazighen (Amazigh people) became aware of the importance of preserving their literary tradition by drawing on modern schools of thought.[3] They realized that their literary tradition was as significant as that of the other peoples, noticing that those peoples did not only preserve their tradition, but also drew on it to create new genres in accordance with the requirements of the age.

During the post-independence period, and in the framework of the near-extinction which threatened the Amazigh language and culture, modern literature in Amazigh has only managed to see the light of day recently despite the fact that its roots go deeper into history.[4] Yet the historical writing in Tamazight was for a religious goal and was, in large part, merely doctrinal, whereas the new style of writing is distinguished by its comprehensiveness and broadened horizons. It has endeavored to crystallize aspects of the Amazigh identity and cultural embodiment. Language in this new form of Amazigh literary writing is not employed merely to convey a religious message, but has become a prerequisite in itself as it constitutes an essential element of identity.

Credit: Tirra Association

The first hints of this new writing started in the forties of the last century in Algeria, and at the end of the sixties in Morocco.[5] The first literary works surfaced during this period, though they were often met with hostility, but its pioneers defied the odds and resolutely began experimenting with creativity in different literary genres that were previously unknown to the Amazigh people. But since my goal in this brief article is not to talk about all the genres of written Amazigh literature, my focus will be on two narrative forms: the short story and the novel. These two literary genres appeared in Europe after the industrial revolution and the advent of the printing press and became important forms of human expression in our modern world. Amazigh literature is not to be excluded from the process of establishing and employing these literary genres.

Since any account of the details of experimentation with these two genres in every country and in every region requires a review of the circumstances that contributed to its emergence and the stages of its development up to the present –something that this brief article does not allow—I will concentrate more on a specific area in the territory of written Amazigh literature, that is the region that speaks Tashlḥyt in central and southern Morocco. This does not prevent me from making brief comparative comments on other regions within Morocco or Algeria, especially given the fact that the produced writing in those genres relatively earlier than Morocco; the first novel was published in Tamazight in Algeria under the title: "Lawālī n Udrār" (The Saint of the Mountain) in 1946 by the novelist Belaid N Ait Ali, while the first collection of short stories was published in Morocco under the title: "Imarayn" by Ed Belkacem Hassan in 1988. However, the first published Moroccan Amazigh novel was published only in 1997 by the novelist Mohamed Chacha,[6] a Moroccan novelist who lived in the Netherlands, where his novel was published. Although I do not currently have accurate data regarding the number of novels published in Algeria up to the present day, I am confident that the amount of Amazigh novels published in Morocco, until mid-2021, is close to ninety novels; fifty-five of them were published in the Tashlḥyt-speaking region, while short stories probably exceeded one hundred and fifty, and again, one hundred and seventeen short stories were published in the Souss region referred to above.

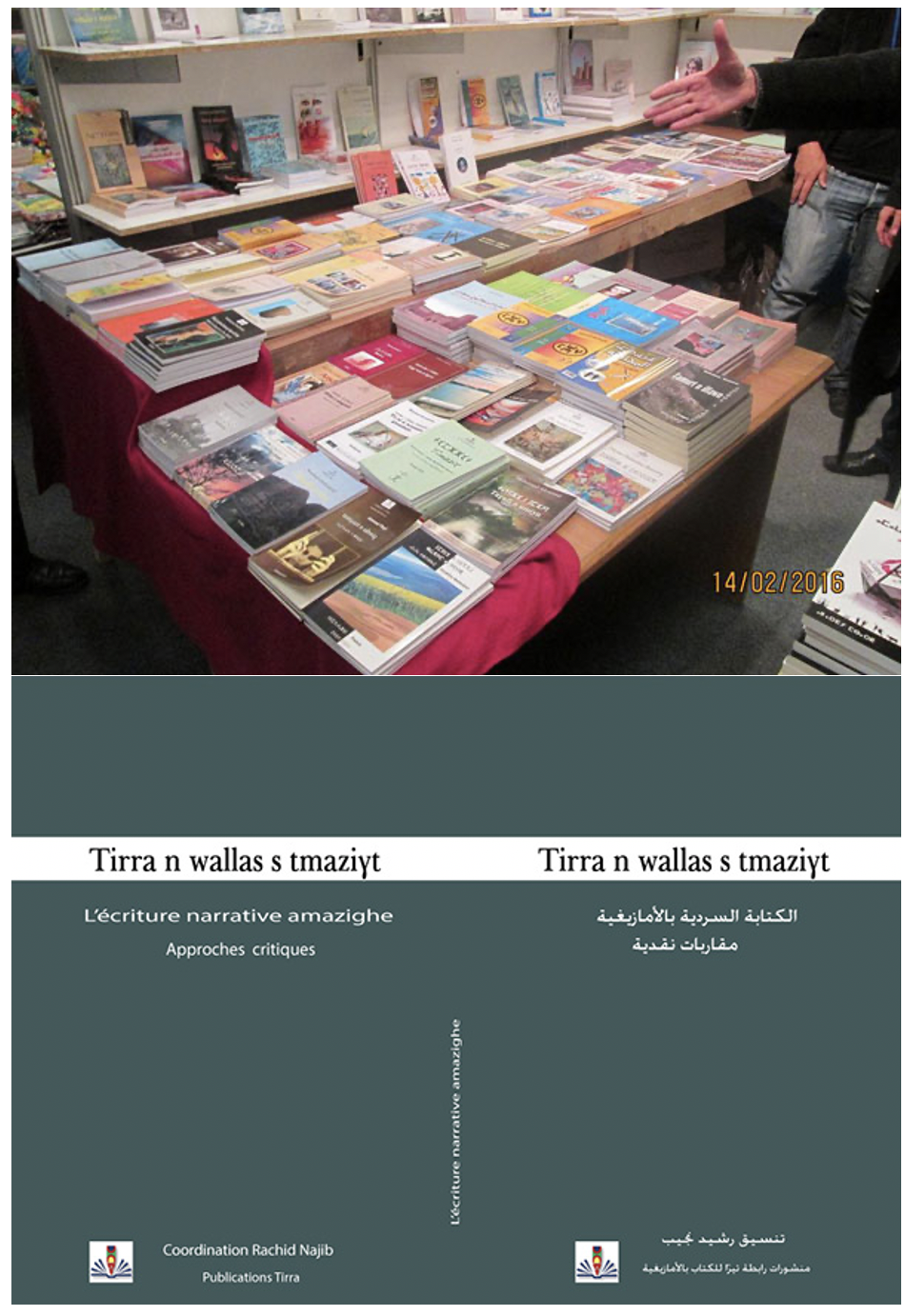

The discrepancy in the amount of narrative literature published in the regions of Morocco is due to various factors. Some of these factors relate to the fact that Tashlḥytophone region had an ancient tradition of writing in Amazigh compared to the rest of the regions. Other factors include the wide geographical space and the proportion of the population, and the relative distance from the impacts of Arabization. However, the key factor in this disparity consists in the emergence of Tirra (Writing) Association for Amazigh writers which, established in Agadir in 2009, continuously works to encourage writing in Amazigh in general and pay special attention to narrative literature among young people in particular, increasing the percentage of publications in the Souss region. The association has published forty novels out of a corpus of fifty-five and seventy-three collections of stories from the existing one hundred and seventeen. Women have played an important role in this literary and narratological achievement. Out of more than seventy writers, the association published works by more than twenty-five women.[7]

The points of convergence and divergence between these two forms in Amazigh literature, be it oral or written, are important to examine. The importance of this question stems from the fact that the Amazigh narrative literature is still in the process of institutionalization. By this assumption, I do not intend to underestimate a number of narrative works distinguished by their quality and originality, but by institutionalization I mean the official and social establishment of this literature. Amazigh language, which is the core of Amazigh literature, was made official in the two countries that currently produce this literature, namely Morocco and Algeria, after the first decade of the third millennium. The Amazigh language was made official in Morocco in 2011 and in Algeria in 2016.

Credit: Tirra Association

Let us start from the indisputable postulate which argues that no written literature originates from the void. Initially, most of world literatures tend to have intertextual links with oral texts that were completed before. Written literature starts to relatively disentangle itself from the body of texts that preceded it only when it achieves a substantial, both quantitative and qualitative, accumulation in terms of production. From there it begins to proliferate through intertextuality. However, since the written Amazigh literature burgeoned under special circumstances, notably its blooming in the margins against contesting forces, it did not accumulate a precociously massive literary corpus and was not widely circulated despite the relatively extended period of its continuous institutionalization. It is not surprising that the Amazigh storyteller and novelist rely on stored, oral texts that they were transmitted to them by their families and through interactions with Amazigh speakers. While embarking on their creative work, such writers succumb to two kinds of authority: the authority of the oral texts, which consist of the subject matter on which they work creatively ( this subject matter, in all its forms, was received somehow through their environment in the form of tales, myths, anecdotes, proverbs and enigmas…), and to the authority of texts written in languages they learned academically.

The majority of Tamazight writers nowadays have never received any academic training in the literature or in the language in which they write. Only recently did Moroccan embrace this literature and launched departments and degree programs. The writers who graduated from those departments are still a very small minority. It is therefore natural that the written literary works, be they stories or novels, intersect with the oral texts that preceded them. The presence of those oral texts varies not only from one writer to another, but also frequently from the same author’s different texts. This intertextual presence may occur spontaneously or deliberately.

The observer of the output of the narrative literary works completed up to this date will find out about the various ways in which the writers deal with the oral legacy in written texts:

A. Some of these works are almost identical to traditional oral texts to the extent that the scrutinizing reader can hardly discern the differences between them, either in form or content. However, this type of text is not the most predominant when one considers the majority of publications. Take, for example, Mohamed Ohmou’s collection of short stories Izmaz n Targin,[8] Mohamed Karhou’s Irzag Yimim[9], and Mohamed Moustaoui’s novel Tiktay.[10] Although these three works are almost exact copies of the oral texts, they are distinguished by the writers’ conscious preoccupation with aesthetics. Mohamed Karho’s collection of short stories is truly a masterpiece, which draws all its components from the traditional Amazigh tale, while Mohamed Ohmou’s fictional works are closer to the traditional tale than to the modern short story. Mohamed Moustaoui’s stories give the impression that they are merely a reproduction of the recorded ordinary speech. These three works are all preceded, in terms of their date of publication, by other narrative works. Yet pioneering characteristics of the modern story are evident in them, either in terms of the issues they raise or in terms of the aesthetic molds in which they were written. As a model for the first type, I would like to mention Hassan Ed Belkacem’s Imarayn[11] and Assafi Moumin Ali’s Tighri n Tabrat"[12] and, as an example of the second type, Mohamed Achiban’s Anzlef.[13]

B. Some writers rely more on rhetorical figures that are based on metonymy, metaphor, and simile that shape the presumed literary image. These figures of speech were formulated in the traditional oral narrative over the centuries and are disseminated in the narrative texts, and sometimes in the vernacular. Writers rely on such devices to endow their creative texts with an authentic aesthetic flavor that characterizes Amazigh narrative and tempers the general taste of Amazigh speakers in different varieties.

The following are some examples of the rhetorical figures that permeate any written narrative text. Sometimes the writer uses them unconsciously. I deliberately gleaned these examples from Hassan Ibrahim Amore’s[14] recently published novel Titberin Tihrdad as this writer seems to have deliberately used them in his text:

- “Ar twargan azal tqd issk” means “they daydream.” If translated literally from Amazigh, it would mean: “They dream during the day while it scorches the horn.” The sentence is loaded with a metonymy used to describe a state of delusion and absent-mindedness. This idiomatic expression recurs repeatedly in the ordinary language. The phrase: “Ar twargan azal,” is a figurative expression based on an implicit metaphor. The phrase "tqd isk" which means “it scorches the horn”, the horn of an animal such as a cow, contains a second omitted metonymy which alludes to the omitted "sun" referred to by the subject pronoun.

- “T fitaghtin a Said" means “you missed the opportunity, Said.” Translated literally, the sentence would mean something like “ O Said, you poured it.”

- “Wa ndadana” means “O year that went by”. It is an idiomatic expression based on a metaphor, referring to a kind of loss of touch with reality or an absence of awareness of current events and developments.

- “Yout Ofalko nes Akjaja” means literally “ his falcon hit the trunk.” This is a wonderful literary image based on a metonymy that refers to failure to hit the target.

- “Izouzl khf wa sghim” means, if translated literally, “ he sleeps on pebbles.” This is a metonymy that describes gloomy and distressing living.

C. Some writers employ the aesthetic structure of the oral tale to convey a modern content as one notices in Mohamed Akounad’s short stories “Ait Touf Tamashout” and “Tabatiti,” published in his collection Tagufi n oumiyn[15] that borrowed its title from an oral tale in a manner similar to Mohamed Ousous’s “Ait Iqjder d Oukhsay.”[16] Some of these writers use common expressions borrowed from tales that have a familiar ring among the Amazigh audience as Mohamed Achiban did in his collection of stories entitled Anzlef.

- Some other writers employ common expressions such as proverbs. This type of expression is remarkably reoccurring in some fictional works such as: Tawarget Demik,[17] Innakofen,[18] and Tamurt n Ilfawn.[19] Amazigh proverbs in Innakofen are abundant and they are used consciously for aesthetic purposes, whereas in Tamurt n Ilfawn they tend to be alluded to by indications that help the reader identify them .

Whoever reviews the output of the accumulated narrative corpus and compares it with the traditional oral heritage will notice that, in addition to those relationships and interactions between the oral and written, there are divergences between them as well. Such distinctions are more palpable since the major goal of the Amazigh writer, when he or she first embarked on the adventure of writing, was to transcend the shackles of orality that reigned over Amazigh literature for a long period of time and chained it to a heavily influential past. The new Amazigh writer is keen on being contemporaneous both in terms of form and content.

Credit: Tirra Association

What distinguishes written Amazigh literature in general, and particularly the narrative genre, is that the space of its formation and reception is primarily urban. It is a literature that has evolved to target a literate public. Thus, in addition to some international capitals as Paris and Amsterdam, Amazigh literature emerged in urban spaces, like Rabat, Casablanca, Agadir, Nador, Oujda, Fez, Tizi Ouzou, Bejaia, Algeria, where it continues to through publication and reading. The village remains the ideal space for traditional forms of narrative. The village is home of erudite practitioners, and it is there that oral worked as produced and transmitted.

Several elements distinguish the written Amazigh literature. The issues it tackles, the characters involved, and the chronotropes within which they evolve adhere more closely to the genres of short story and novel rather than tales and legends. I previously claimed that the writers of the Amazigh short story and novel rely on two different sources: the ancient Amazigh oral heritage of their youth and the written sources of their academic training. The latter source is illustrated by several forms of intertextuality:

- an instance of this intertextuality resembles the art of ‘al mu‘āraḍa’ or “opposition” in poetry, which is structured around the production of a literary text that imitates a written text that preceded it. An example of this poetic opposition lies in Lahcen Zahour’s novel Aghyul d Wizugen[20] which imitates an ancient text by Lucius Apuleius The Golden Ass, which is considered the first novel ever written.

- Intertextuality with the religious heritage, such as the Qur'an and Hadith. For instance, Tamurt n Ilfawn refers to Surah An-Naml ( Chapter 27th in the Qur’an), while Tawarget d Imek refers to “Adrar n Qaf,” a mythical mountain mentioned in some theology books like Badāi‘ al-zuhūr fi gharā’ib ad-duhūr.[21]

- Intertextuality with poetry collections, modern Amazigh novels, quotes by philosophers and thinkers. This can be illustrated by Fadna Faras’s novels Dawa ouchidad n tchaka nm[22] and Ebiw N Tarir,[23] and Hicham Goghoult’s Tamdayat d and Sinsi.[24]

- Intertextuality also takes place by evoking characters from ancient Amazigh history, like in Zahour his collection of short stories entitled Tayri d Izilid[25] in which he refers to the character of Cleopatra Selene, the wife of Juba II. Also, as in Tarik Ben Ziyad’s collection of short stories Issggassn n Tkrist,[26] and lastly Salh Ait Salh’s allusion to the character of Juba II in his collection of short stories Tojojt n Irifi[27] in a similar way to what Zahra Dikr did in her novel Tiske Tarjdalt,[28] which was inspired by "Tin Henan," the historical figure that the Tuareg consider their grandmother.

The Amazigh writers endeavor to simultaneously sow the seeds of and establish narrative forms that were previously unknown on Amazigh cultural soil, and to ingrain their robust identity in the Amazigh culture on the other hand. They do so with a growing awareness that a decisive break with their great legacy of narratives is indeed flawed and complicates their task. The more they try to burn the stages, the more they fall into ambiguity and vagueness that sap literary creativity. Such ambiguity and vagueness only strain the readers and deprive them of that sacred pleasure that secures a positive interaction between the writer and the reader. The Amazigh writer has begun to understand and appreciate this fact, an attitude that gradually provides the modern Amazigh narrative scene with original creative works from which readers derive the pleasure that literature in other languages has long offered.

[This article has been translated from the Arabic version by El Habib Louai.]

[1] Ibn Khaldoun. Al-muqaddimah (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-Lubnānī, 1999),175.

[2] Emile Laoust. Contes berbères du Maroc ( Rabat: Institut Royal de la Culture Amazigh et université Mohammed V, 2012).

[3] The Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture has recorded and published a great deal of oral literature, for instance the anthology entitled Imarirn: Twentieth-Century Renowned Ahwash Poets which contains fifty poets.

[4] For ambiguous reasons, history has not preserved for us relatively long texts with the Libyan script or Tifinagh script from which it branched, except for the tombstones, yet a great deal of what was written in Arabic script has reached us after the Muslim conquest of North Africa. We have, for instance, Ibn Ghanem’s pamphlet, and the two books “Al-Hawd” and “Ocean of Tears,” two religious homelies composed by the jurist Muhammad Ali Awzal, who lived until the mid-eighteenth-century.

[5] The establishment of the Amazigh Association for Exchange and Berber Academic Cultural Research in Paris coincided with the establishment of he Moroccan Association for Research and Cultural Exchange in Rabat in the same year 1967. See The Amazigh Cause in Morocco and Algeria. Roots and Challenges for More than Two Centuries by Houcine El Yacoubi, second edition (Agadir: Sous Impression Agadir).

[6] Mohamed Afkir, Return to the Narrative in the Moroccan novel written in the Amazigh language: The Borders between the Real and the Imaginary (Ait Melloul: Terra Association for Writers in Amazigh, first edition 2019).

[7] See statistics issued and updated every year by Terra Association for Writers in Amazigh.

[8] One of the most famous collections of short stories published by Mohamed Ahmou is entitled Izmaz n Trgin (Agadir: Aqlam Press, 2008).

[9] The short story collection Irzag Yimimis the first by Mohamed Karhou published by Dar Al Qalam Press in Agadir in 2010.

[10] "Tawssna” publications, Idoukl Press in Rabat, 2012.

[11] Al-Maarif Al Jadida Press, Rabat, 1988.

[12] Publications of the Moroccan Association for Research and Cultural Exchange, Fidérant Press, Rabat, 1998.

[13] Tirra publications, The Central Press of Souss, 2020.

[14] Publications of Tirra League for Books in Amazigh.

[15] Tirra Publications, Dar Assalam Press, Rabat, 2015.

[16] Publications of The Moroccan Association for Research and Cultural Exchange, Al Maarif Al Jadida Press, Rabat, 2009.

[17] Mohamed Akounad’s first novel, Bourgrag Press, Rabat, 2002.

[18] Mohamed Oussous’s first novel issued by Tirra, Central Press, Ait Melloul, 2017.

[19] Mohamed Akounad’s third novel, Dar Assalam Press, Rabat, 2012.

[20] Tirra publications, Central Press, Ait Melloul, 2018.

[21] Published by Mohamed Al Hanfi, Dar Al Koutoub wa Al Wata’iq Al Qawmiya, Cairo, 2008.

[22] Tirra Publications, Central Press, Ait Melloul, 2015.

[23] Tirra Publications, Central Press, Ait Melloul, 2020.

[24] Tirra Publications, Central Press of Souss, Ait Melloul, 2020.

[25] Tirra Publication, Dar Assalam Press, Rabat, 2014.

[26] Aqlam Press, Agadir, 2009.

[27] Ibid, Dar Assalam Press, Rabat, 2015.

[28] Tirra Publications, Central Press of Souss, Ait Melloul, 2018.