[This article is part of a special dossier on Morocco in the 2022 Fifa World Cup. This particular installment is the introduction. Other articles will be published progressively and will be added to this introduction as they are. Read Zakia Salime's installment, "Soccer, The New Field of Feminine Identification," here.]

The Men’s football World Cup in Qatar has been a joy to watch from Moroccans’ vantage point. The team’s successes on the pitch have drawn support from across the world as the story of an underdog overcoming footballing powerhouses and giving hope to other teams to, one day, win the championship. Domestically, the football feats of the national team made Moroccans happy, taking a month-long break from their pressing socio-economic and human rights issues.

Outside of the pitch, commentators have noted the many subtexts and underlying stories associated with this Moroccan team: from its representation of Africa and the Arabs on the world stage, the diasporic origins of certain players, the values of hard work, belief and success they espoused, or the joy of seeing players celebrating with their mothers, everyone found something to celebrate the Moroccan team’s achievements

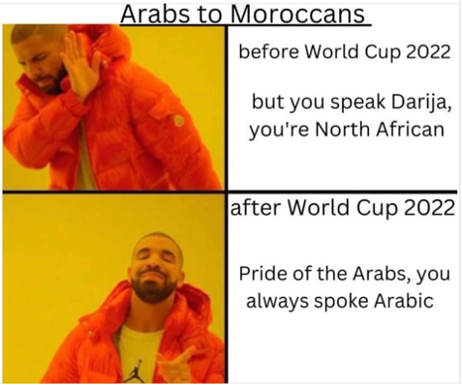

Amid the excitement, and now that the dust of the games has settled, we must recognize that many did not expect Morocco to have traveled so far into the competition. Furthermore, Morocco and Moroccans are not used to the amount of global attention they received in just a couple of weeks. The success of the team reminded the world of Morocco’s existence, sending Google searches of its name skyrocketing. A Kenyan newspaper has recorded that the semi-final match saw a 4,700 per cent spike in Google searches. In the space of a few weeks it has gone from unclaimed periphery to flagbearer, as the meme below illustrates amusingly.

Meme shared by the Moroccan scholar Hisham Aidi on 13.12.2022

This team has captured the imagination of football fans from across the Global South. Football, supposedly one of the fortresses of global capitalism, especially when FIFA is involved, was thus subverted to accommodate new forms of solidarity. Certain responses were evocative of ideals about decolonization, revolutionary movements, and postcolonial peoplehood.

However, a large section of this team’s media coverage did demonstrate that certain backwards (and perhaps even colonialist) practices die hard. Like any other phenomenal rise that takes observers aback, commentators were left grasping for analytical keys to contextualize the Moroccan football team. Large media outlets scrambled to find analysts and commentators who could explain the event to their audiences with variable levels of success. The overall tone of the team’s World Cup run is indication that we need to find analytical terms to conceptualize what happened in Qatar: How can they explain this country to outside observers? Which Morocco does this football team evoke?

In academic circles, Morocco and Moroccanness are often subsumed under the heading of ‘specificity’ which often reads as ‘contradictions that somehow hold together.’ For example, in Emily Gottreich’s survey history of Jewish Morocco, the author puts in succession the country’s integration of religious minorities, moderate branch of Islam, geo-cultural location, its embrace of tradition while embracing globalized modernity. The idea of Moroccan ‘specificity’ has been adapted into a theory of Moroccan ‘exceptionalism’ in the Middle East and North Africa to explain its particular road toward political change since the Arab Spring. Yes, Morocco is unique in terms of its geopolitical situation, migratory history, and demographic and religious formation, but it is not an exception. Exceptionalism, while useful in some cases, has proven to be very limited as an analytical lens for a nuanced understanding of Moroccan identity formation.

Claiming ‘specificity’ has clearly felt insufficient during the World Cup since it merely signals a statement of plurality rather than analytical consistency. In addition to its conceptual shortcomings, specificity risks leaving Morocco in a mystical place of epistemological unintelligibility, implying that only a handful of scholars and experts can turn paradoxes into intelligible narratives. This particularly evokes Carleton Coon’s misconception (and unfortunately largely circulated) of Moroccan identity as a mosaic. We recognize the very nature of unequal logics of knowledge production mean that smaller countries have to contend with external narratives produced by institutions in the Global North or foreign media. Some of this coverage has visibly sought to explain Morocco in terms more palatable to large, oftentimes lay readerships, resorting to analytical categories that may not sound quite suited for judicious understandings of race, identity, citizenship, gender and the collective. The need to inform and the desire to engage with an unfolding historic moment should lead us to wonder about what is gained and what is lost in adopting certain specific ways of writing to make Morocco legible. Do we run the risk of making some stories about certain readers’ own preoccupations rather than about Morocco itself?

Instead, the World Cup run has made it more urgent than ever to offer a reading of Morocco and Moroccanness as a country that makes sense in its own right. Moroccan scholars in Anglophone academia have made crucial interventions in the debates, complicating the questions of identity, race, and gender.

Hisham Aidi has read the Moroccan World Cup run at the intersection of “dissident Third World solidarity” and the “multifaceted nature of Moroccan identity itself: simultaneously Arab, African and Amazigh.” Aidi tackles specifically the linguistic reality in Morocco with its geo-political location (ideologically and in space) in order to deliver, what he calls, the “Moroccan cultural brew” which has “arrived in Qatar” and from there, to world audiences. Aidi’s timely intervention did, however, contain elements that we believe need to be critically nuanced, specifically regarding the relationship between Amazighity and Arabness. Amazighty has never been constructed as an anti-Arab project. It is rather an endeavor to build a pluralistic society in which all the dimensions of Morocco (and Tamazghan) identity could stand on equal footing within the democratic states. Aidi’s adumbration to the noxious effects of “en-Gulfment” (khaljana) of Tamazgha, which plays out in the form of anti-revolutionary (or even explicitly reactionary) actions in Tunisia and other places in Tamazgha, need to be taken seriously. Aidi’s crucial reflections could be read in tandem with Brahim El Guabli article “The Afro-Amazigh World Cup Debate Revisited” in which he examines the significance of the emergence of the Afro-Amazigh consciousness during the World Cup. El Guabli specifically argues that what has been missing was an engagement with the politics of Amazigh Indigeneity and its transformation of the debate about identity within Tamazghan societies.

The identitarian and civic implications of the Moroccan world cup were further complicated in other articles. Aomar Boum and Brahim El Guabli defined Moroccan pan-nationalism contextualized the team within a longer historical trajectory, relating to histories of colonialism, migration, pan-nationalism, xenophobia, and cultural pluralism. Boum and El Guabli define Moroccan pan-nationalism as an affective bond and a belonging that “transcends the physical boundaries of the country… that transcends languages, cultures, passports, identity cards, and myriad forms of identification.” This transnational bond is not a catch-all, for the two authors, but a way to find a recurrent configuration of “multiple languages and hyphenated identities that its players straddle” - which is confirmed by a coming together around shared values of niya (faith and belief) or similar affection by players for their mothers, which all Moroccans can recognize themselves in.

Nizar Messari and Jonathan Wyrtzen offer another attempt to systematize Moroccanness and its nationalist deployments that is accessible to a larger and lay public. At its core, Messari and Wyrtzen’s article successfully identifies how this Moroccan team, and the country, are best understand through the “both/and” device:

Defying any attempt at either/or categorization, what the Moroccan team captures and embodies is the distinct “both/and” reality of Moroccan global identity, history, and experience. These Moroccan paradoxes and tensions have been on full display in Qatar.

They go on to list the many ways in this team, and Morocco, are “both/and” without being contradictions: both European born and Moroccan; both francophone or hispanophone and Arabic/Amazigh speakers; both pro-Palestinian and having normalized relations with Israel; both a smaller team and a World Cup semi-finalist. Avoiding any prescriptive language, the authors leave it up to the readers to expand on the “both/and” device and how it could be deployed further.

“When I tell people I’m from Morocco”

These essays should be read together. They are attempts to offer an intelligible framework to capture Moroccanness in its complexity and plurality, beyond the short-term analyses that may lack the depth of long-term preoccupation with Moroccan issues. They take us one step further out of the pigeonhole of provincialized knowledge where scholars of Morocco, native or not, find themselves too often: forced to justify a focus on their country, by describing all the ways it informs more commonly known cases, rather than systematize and analysis Morocco in its own right, and then explain how it can inform others.

In this series, we have asked different scholars from or of Morocco to reflect on this event from their perspective. In addition to their scholarly expertise, these contributors have an intimate relationship with Morocco, allowing them to share their insights about their reaction or interaction with the event of Morocco’s rise in the World Cup as it unfolded during the tournament. Specifically, we noted the opportunity to revisit the narratives of Moroccanness that pervade the coverage of its World Cup run, to scrutinize them critically and eventually displace them on the basis of our own knowledge and observations. In the first instance, how have they experienced the Moroccan team’s success at the football World Cup? We have invited them to reflect on the approach they deploy to make a Moroccan social phenomenon intelligible: whether they embrace plurality, normalize the contradiction, find a way out of this dichotomy or, as Messari an Wyrtzen write, they answer “so what” and perform on the (proverbial) field.

This series suggests that the Moroccan World Cup run could provide us an opportunity to revisit critically how narratives are formed about certain countries and whether key events help displace them – a recurring discussion since the events of 9/11, the Green Revolution in Iran, the Arab Spring, and the 2019 Arab protests. What does it mean for a country to be known? How does one event change, confirm, or revise certain core tenets? On the whole, this series interrogates the value of knowledge in MENA studies, how we approach this region, the relationship between scholars and their object of study/belonging, and the possibilities of change toward complex yet intelligible knowledge. These short contributions elicit fascinating observations about Morocco’s relationship with the African continent and the Palestinian question; the role of digital media and the new forms of nationalism; the crowds and ideas about the Arab street; youth aspirations for change and success; Amazigh identity and the geopolitics of cultural activism. While the Moroccan football team has won hearts across the world for its daring achievements against impossible odds, so too can the contributors to this series of articles dare to change how Morocco appears on the global stage of knowledge production.