He was paging through her pictures on Facebook. He’d discovered they were set to public. Backwards through the decades he went, from her fifties to her forties and thirties, then the university years, and finally the photographs from school. They had come across one another a while ago, here on this site; taken by her sharp comments and sardonic humor he had added her to his list of friends. The pictures did not tell him much, but one day he woke with a start in the early hours of morning: something deep in the past, recalled. He got out of bed and switched on the computer, making straight for the blue-blocked page in order to click back through the albums, and when he came to one in particular he sat frowning and peering at the screen. It dated from her time at university and showed her with hair cut short and her dark-brown face, the very image of one of the celebrated beauties of that age, the happy Seventies, whose fame had flared like a meteor and quickly died: Hayat Qindeel—a darker, more classically Egyptian-looking version of Soad Hosni, who had never achieved the fame she deserved and who had soon vanished from the world of cinema and celebrity. It was said she’d died.

The woman was Noura, the Noura he’d known all those years ago. How was it he hadn’t made the connection till now, till this flash of inspiration between sleep and waking?

Holidaying in Marsa Matrouh, the summer of ‘79. Abdel Moneim Madbouli playing Baba Abdou on TV and the vacationers, clustered round the screen, watching his antics with a terrifying intensity. She was six years older, sitting among them with the same short hair, that same slim build, and looking on impassively.

He made the most of every chance he had to get close to her—in the television room, down on the beach in her one-piece blue swimsuit—and in a matter of days (a substantial slice of the holiday as a whole) they were side-by-side on the sands: him constructing a castle and her beside him, dispensing instructions and telling him about the strength of the German economy achieved though the country had only emerged from crushing defeat a few years previously. As though she were running over facts that would help her maintain her academic success. She was recently out of high school and intending to enroll at the faculty of economics and political science; he, heading for his first year of middle school, understood little of what was said. She was going to learn to drive, she told him. Her father, Dr. Emad, was going to give her his old orange VW Beetle so she could drive herself to class.

Like a summer-night’s dream the holiday came to an end and there was a new reality to contend with. He lived in Doqqi and she lived in Heliopolis (from the city’s far east to its furthest point west) and the six or seven years that lay between them, coupled with a profound shyness, prevented him from calling her up. But he went to the Orman High School and she would now be going Cairo University, and this, by luck, was close to both his school and his apartment. Each afternoon he would exit the classroom and with his heavy school satchel stroll the few hundred yards to the wall of the university campus. Of course, security would never let him pass: how could he get his twelve years up in the guise of a university student? Drifting up and down alongside the wall he had managed, by dint of inquiry and observation, to pinpoint the location of the political sciences faculty and establish an observation post within sight of its vast edifice. For an hour, for two, he would stand behind the railings on the off chance of catching sight of her amid the crowds. Weeks of the new academic year went by and still she did not show. Just crowds of young students in a state of heedless joy he longed for and envied, as though they were on some eternal school excursion. He came every day after school and never saw her.

The autumn sun, still with its summer brio. For a long while he stood there by the famous wall watching the youthful horde within: a solid, swaying mass of undifferentiated humanity without heads or bodies. Admitting at last the unlikelihood of seeing her, yet unwilling to return home so defeated. So what if he was a little late? Thursday today and tomorrow the weekend. Turning his back to home he walked along the wall, heading into the unknown. His world had always ended at these limits: previously the wall of the Orman Gardens, and now lately the university wall where he came to lurk each day. Into uncharted territory, then. When we are twelve we are allowed go further afield than children of eleven. Through the railings to his left the political science faculty fell behind and was replaced by the faculty of commerce complex, around it a fearsome swarm many times more numerous than the politics’ students.

And he walked and he walked, until he saw a grim grey building protruding from the wall just as it bent left into Sudan Street. Reformatory, the sign read. In his mind’s eye he saw dark corridors stretching endlessly away with bed-filled dorms like hospital wards on either side, and heard disquieting shouts growing louder and then the voices of young children and boys his age, an blend of sharp notes and barks which echoed and swelled as though they pursued him. And now a light at the end of the corridor and him, in flight from the darkness and the alarming cries, trying to get there.

He would never see her again. The summer was over and her with it. The cries receded and faded away, blending into the growl of traffic in Sudan Street with the first shock of dazzling daylight. He had turned left with the wall. The first time his feet had trodden this street unaccompanied. Why had they called it Sudan? Because the Southern train passed through here and its eventual destination was (must surely be) Sudan? The university’s green railings still running along on his left as they had been since passing the reformatory. He was now by the campus’s west wall, walking and walking, further and further away, some unknown distance from his own front door, with his satchel growing heavier and the wall still stretching ahead—though now the faculty buildings and the reformatory were vanished and through the bars great swathes of bare ground could be seen, on whose far side, at the limit of sight, a line of tall palms ran parallel to the east wall: about a kilometer away, at the university’s main gate, the dome atop the administration building was a brass breast gleaming, sunlit, over the canopy’s green cloud. And suddenly, there to his left, an open steel gate beneath a sign: Teaching Farm, Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University. He’d never imagined the campus to be this vast. That it had a “teaching” farm, no less. He had a rough idea of what this must mean: the faculty of medicine had a teaching hospital where students pored over the bodies of God’s humble servants, so here was a teaching farm for students of farming. Made sense. There was no guard or soldier or doorman even, an anomaly among fiercely-guarded gateways of the university, and without thinking he turned in, and onto a shaded path lined by high trees. As he walked on the more tightly the trees entwined and the sunlight slowly lost its edge until at last the sky opened above him, a gap in the green tangle, and his footsteps shifted onto sun-warmed soil, only to be reclaimed once more by the humid shade. He walked entranced. It was as though he had discovered a rainforest in the heart of the city. One chance turn taken from your path and you stepped out of time.

He remembered the war, the radio broadcasting endless songs of patriotism and zeal. Words fell silent and the guns spoke. Standing before the mirror, his rifle a stick slung from his shoulder on thick cord. He began his marching drill. Marching without moving down a road with no end and all the uniformed children before their mirrors, an iconic image transcending cultures and generations. On the spot, stepping faster, knees rising and falling in tandem, then picking up pace, running now, not marching, and singing out another anthem, Departing, departing, our weapons in our hands. Returning, holding victory’s banners high, its rhythm faster, running faster, and seeing himself drawing further and further away until he had crossed over to the other side. He couldn’t say what it was exactly that had happened, but from that day forwards he hadn’t been the same. Folk taboos about staring into the mirror were alarming enough—they said it turned you mad—but the warning seemed intended more for girls than for boys, its purpose, like most popular wisdom, to enforce male dominance by sabotaging the slightest manifestation of self-regard in the women of the future. That day he had become two: one at play, the other looking on and sneering. There, the soldier-boy in the mirror and there, the other, observing him absorbed in his routine, watching on and yet unable to halt the motion of the very body that looked so foolish and childish in the smooth silvered surface. Subsequently, some thirty years later, he would read Jacques Lacan on “the mirror stage”. The French psychoanalyst’s mirror was where a child discovers itself, sometime between the ages of six months and a year and a half, a moment the great man regarded as the first stage in the subject’s alienation from itself, before the great alienation that accompanies the acquisition of language. Language is alienation? The word is a stone / The word is a death, wrote the poet. Yet he had been a little over four at the time and words had been his playthings: singing the songs of war. He hadn’t been a child that day, and it hadn’t been childish play; even the sandcastles on Rommel’s Beach in Matrouh had been constructed with the one purpose of ensnaring her: a clever trap set by a seducer yet to reach his twelfth birthday. And she had fallen for it. She had come to play and to build with him and to give him the advice of someone six years his senior. Coming out of the sea she would slip white satin shorts over the blue swimsuit, the shorts themselves fringed with thin blue satin stripes stitched onto the white. With neat movements she would brush the soft grains from her slender feet then put them away into socks. What’s the most powerful nation in the world? he had asked her, and she had answered him with the conviction of an eighteen-year-old girl: If we’re talking the economy then I’d have to say Germany. The Nazi forces, she explained, had occupied this very city. Their military command was headquartered on this very beach. They had been advancing towards Alexandria at the time, Egypt’s second city, and the allied forces had met them at El Alamein and defeated them.

He was still walking, as though drugged, down the long shadowed path through the teaching farm. Sunlight trickled through the knotted branches overhead and the reek of chlorophyll and an overpowering humidity fogged the three-p.m. prelude to the day’s intoxicating sundown. He was suddenly conscious of strange sounds, a clucking of chickens, and coming back to himself he saw a wire-meshed enclosure to the left of the track behind which hundreds of hens and cockerels were imprisoned. Their feathers glowed bright red and orange in the magic light. In the same instant every one of the chickens became aware of the presence of a foreign body advancing along the track beside their coop. They fell silent and a sinister hush descended; scrags quivering, red combs rising, thousands of tiny round eyes tracking him as he passed. And then their goldfish memories—their poultry memories, perhaps—promptly forgot him and they went back to their muted clucking, pecking illusory grain from the ground. He left the birds behind and pressed on down the path. On either side, narrow tracks branched away, leading to other parts of the farm and, glancing down one of these side-tracks as he passed, he saw in the distance dark figures moving behind the same mesh used for the chickens. He paused for a moment, peering, until his vision sharpened and he recognized them as goats. Their far-off bleating faint and broken came to his ears.

He recalled that in University Street, by the Saeediya High School, there was a green-painted kiosk which bore the legend, Produce of the Faculty of Agriculture, where his father would sometimes go to buy lightly-salted white cheese made with goat’s milk and orange-blossom honey, green limes, yellow lemons, pickled and preserved with safflower, crates of taimur and founes and sannara mangoes, date and carrot and apricot jams, impossibly creamy white buffalo yoghurt, cows-milk yoghurt tinged with yellow, and fresh-laid eggs for less than market price. Just like the currency market, or the old bourse for long-staple cotton, there was an egg exchange whose prices dipped and rose daily. But not there! The eggs there were top quality and subsidized, too. So his father would declare with finality.

On the basis of some basic geometric and geographical calculations he deduced that this endless path would led him eventually to University Street, maybe to the kiosk itself, but the shroud of trees, their density, prevented him from seeing all the way to the horizon. When he found a rock fit to sit on he settled down at the side of the path to recover his breath, to consider when and how he’d head home, and to try to persuade himself that he’d lost her forever to the crowds. Had he been a little older he would of course have had a pack of cigarettes, would have taken one out and sat on this rock to smoke. The time and place were ideal for it, but smoking was to come later, in the near future.

Beneath the towering palms there was a flowerbed, ringed by the same wire mesh, and on this mesh hung a small tin sign on which was printed in black marker, Psychoactives: shoots of medium height with leaves as deep a green as mint or molokhiya, others with tiny leaves and white and pink flowers, and all with tags that gave their names in Arabic and Latin script—the last unreadable due to combinations of letters that he, with his limited experience of English, had never known combined. He peered closer and read the Arabic: acacia, mandrake, Ghanaian iboga, Yemeni khat, Indian hemp, nightshade, Mexican morning glory. The last two appealed to him. He was standing with his fingers threaded through the mesh, staring at these untouchables and asking himself why they would name one drugged herb Nightshade and another Morning Glory, when, startled by something shifting at his feet, his heart lurched in terror. Just one of the smaller goats—it must have slipped out of the enclosure—probing the ground around him with its muzzle and eating what grass and fallen leaves it could find. He left it to graze and returned to his rock, thinking what he would do next. Without warning darkness descended on him, a green dark like that which accompanies a stiff blow to the nose, but the dark had none of the bloody tang that a blow to the nose brings, rather the keen and heady fragrance of sap at its pre-winter height. The goat, having finished off the gleanings on the ground, now turned to the fragrant treasure behind the mesh, nibbling the leaves which protruded through the holes and pulling at the stems, tugging them closer and gobbling down the buds and branches.

Maybe she could come and babysit him and his brother, who was younger than him by four years. They weren’t kids. Or rather, he in particular wasn’t a kid. Plus, babysitters as a concept were not that common in Egypt, or not in his family to be exact. She was simply asked her to stay with them both, for the two weeks his parents would spend on their umra. It would help you, too, it was put to her. You won’t have to drive your orange Beetle from Heliopolis to Giza every day—the apartment was only a stone’s throw from her faculty.

The first day of the trip, he and his brother got home from school at three. The parents had set off for the airport in their uncle’s car that morning and Noura, so they had been informed, would be returning from the university at six. There was plenty of time to play, and to plan as well. Of course, no study or schoolwork of any kind would get done. There were two bedrooms in the apartment he thought to himself: the big one with the big bed—his parents’—and the smaller room with its two small beds for him and his brother. For the two weeks she’d be staying Noura would most likely sleep in the larger bedroom or on the sofa in front of the television in the living room. After a lunch eaten cold from the fridge the pair became engrossed in a game of Monopoly and as they played he began sorting through his rich store of terrifying tales of djinn and unquiet souls to tell the younger boy. He told him about Aziza Makrouna, the woman who lived in the Old Doqqi market and fraternized with djinn and who’d established such absolute control over her neighbors’ daughter that she could compel the to girl move about according to her whim, to make her strip naked in class. He told him about the haunted apartments in the neighborhood: the flour-seller’s place in the same market district which was full of female weasels which would run and leap about all over the apartment then vanish without warning. He told him about the apartment in Mesaha Square once owned by Dr. Mousa, a university professor murdered years ago by a burglar whom the neighbors still saw through the windows at night, roaming the apartment’s empty darkness in his dressing gown. He told him about a boy in his class who had got up to go the bathroom one night to find a white donkey in the gloom of the living room and next to it a man dressed in a robe and banging his palm on the huge taut disc of a drum which he held in his other hand. The man had lifted the boy up and set him on the donkey’s back then walked with him towards the open balcony, and would have walked out with him, too, had the boy’s father not suddenly appeared and switched on the lights. Man and donkey had vanished and he’d tumbled to the floor. Then more, and more elaborate, stories of the same kind, reminding his brother that they would be more or less alone at night, that Noura would be out of reach and wouldn’t come rushing to comfort them in their hour of need. Planting the idea without stating it openly. The task of persuading Noura to be left to his brother’s notorious tearful nagging—or to be precise: the task of compelling Noura to sleep with them in their bedroom without any intervention on his part. However common sense dictated that for reasons of space and probity, she would be sleeping with the brother in his bed. Here, the second part of the plan came into play: he proposed to his brother they move the beds together. That way they could sleep safe and sound, side-by-side, like they were lying in one big bed! The brother was instantly enthusiastic and pooling their strength they shifted one bed up against the other so that the narrow passage between the two disappeared and the bedroom became unfamiliar and unbalanced.

Noura returned with nightfall as though this was the home she always came to: not the special event, the cause for celebration, that he’d pictured. She opened the fridge airily and prepared her supper—heating it, not eating it cold as they’d done—and the three of them sat in the living room, watching television and making small talk. The evening drew out, time passing slowly, and then they were into night proper. Thursday, and an old play on TV, meaning that the long-awaited moment was to be deferred yet further: stage plays running much longer than movie, on the whole. Whatever else, he had to get to bed before them, firstly to leave his brother free to deploy his weepy blackmail when the moment came for bedtime without any kind of intervention being demanded from him, and secondly, so that he could reserve the only spot he wanted on the mattress. Unfurling a large blanket borrowed from his parents’ room he slipped beneath it and settled directly over the join between the two beds. Positioned thus, at the midpoint of the space available, he now commanded both flanks.

He lurked under the covers in the dark, waiting. Light came through from the living room outside along with the TV’s burble and Noura and his brother’s laughter. He was restless but unwilling to let himself work off his nerves by tossing about in case he missed any hint they were getting ready for bed. His ears were alert as a bat’s. And maybe he did doze off for a moment but when the bedroom light was switched on he came to: Noura, in a robe, staring in astonishment at the sight of him lying where the two beds’ joined. He heard a laugh, “Why are you lying like that?” and gave no answer, pretending to have fallen fast asleep again. His movements had betrayed him, he knew, but the laughter told him she didn’t mind. The light went off and either side of him the others got in, Noura on his right and his brother to his left. Her shoulder brushed his, relaxed and relaxing. He felt warmth steal through his body and his heart beat so hard he was worried she might hear it and his secret be out. Once more he waited, but this time with his shoulder against hers in the darkness, her presence electrifying the snug space beneath the blanket. He grazed her foot lightly with his own. His feet were icy with fear and excitement and startled by the cold she pulled away for a moment, but then brought her foot back, where it settled into innocent contact with his own. About an hour went by. From the sound of her breathing, even and threaded with a delicate snore, he had almost convinced himself that she was asleep, and he grew bolder. With contrived serendipity his hand came down on her thigh. As his hand touched flesh his heart hammered. Her nightgown was hiked up and sliding his hand higher he found that the bare skin kept going, on and on— her gown was up over her waist!—and now he was erect, his breath thick with arousal. And then, at last, he came to the soft cotton triangle, the full weight of his faculties and awareness focused in his hand. Beneath the cotton he could feel the thick brush and the soft contours that ran through it and beneath it. He was asking himself what the next step would be, considering with a mind on fire how to tackle the cotton’s delicate barrier, when all of a sudden she was rolling over and onto him, bracketing him between her thighs so that the selfsame triangle settled over the bulge in his shorts. He never knew how long they stayed this way, nor when they slept, but he awoke a little after dawn, damp for the first time. He had to get up early to go to the crammer classes he attended on the weekend. “A group” they called it and most days the sheer pointlessness of the exercise had him lingering unenthusiastically, but this time, to avoid a morning confrontation he had no idea how to handle, he rose without hesitation. He put his clothes on over his clammy underwear and went downstairs, out into Doqqi’s empty, Friday-morning streets, a mixture of emotions accompanying him on his way: a feeling of pride and sacredness; the sense of having made the crossing into a new era. In class he was distracted, the algebraic equations before him a set of more-than-usually-obscure sigils, and on his return the little mosques were spreading their mats out on the sidewalk and the loudspeakers were clearing their throats in anticipation of the call to prayer. When he opened the apartment’s front door he found her sitting and studying at the dining room table. She lifted her face to him and gave a sly smile. He was flustered: “What?” “I’ve missed you,” she said.

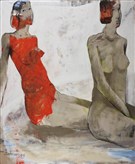

The goat was dragging its back legs and swaying left and right in its slow progress back down the track that led to the enclosure. Noura, with the six years she had on him, had always seemed to be speaking down to him from some vantage point of beauty that, for its tender kindness and generous welcome, was somehow unreachably high above him; her body, brown and slight and beautiful, had been the first sensual idol he had known and touched and breathed in with the totality of his flowering awareness. As for now, well, the difference between forty-five and fifty-one was not the same as that between a child of twelve and an eighteen year-old, and the idol stretched out beside him in the apartment in Rehab City was no longer spare and slender as before. Her car, though an orange Volkswagen, was not that Brazilian-made Beetle from the seventies, but a 2014 Golf. Dr. Noura Emad, professor of political economics at the Swiss University in 6th October City had not entered her fiftieth year “with all her apricots ripe on the tree” as Mahmoud Darwish once sang; now Noura’s apricots were bottled, dried and boxed, processed into paste, a preserve made and sold by the faculty of agriculture in the seventies. And who was to say that an eternal child and man of abiding middle-age such as he should set any store by fresh and ripe at the expense of that biting sweetness.

[Translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger. You can read the Arabic here]