Contemporary media art and digital archives have submerged as (trans)media of a collective experience and intelligence that materialize the deep time of the present as much as the speculations of the future. The interrelation of (new) media art, digital archives in a space of timeless practices and forms, and assembled images are shaping mediations of affective, technological, and above all agential realities. Artistic research and user-generated forms of trans-subjective engagement constitute new medializations of the archive and foreground other relational realities of post-cinematic, digital images and their mediums in the contemporary art scenes and social media platforms of artistic collectives of the MENA region.

The last few years have been characterized by a new formation of the archive of events, and archival images in interactive networks that have developed an intensely creative, dynamic, and experimental cine-media culture. The emergence of assemblages of contemporary media art, the novel interfaces of documentary film archives and their interconnectivities, and interactive methods of documentary juxtapositions have emerged as new digital processes of creating alternative collective memories whilst reconfiguring the visibilities of crisis.

Such superimpositions of new materialist media cultures and thinking have foregrounded an agential aesthetics of crisis in the aftermath of disaster politics and the dismembered body in combat zones. These aesthetic methods, interactive strategies and affective materializations of crisis and (physical) trauma are subjectivizing the very technical media of recording and displaying life on the ubiquitous screens of our post-digital lives, and it is the documentary image and its economy that has helped the digital become an imaginative filmic medium in its own right.

The documentary image in film and beyond has become, over time and in digital circulation and alterations, the witness of political crises and consumer capitalism. It has displayed, witnessed, and generated a decisive reconfiguration with the digital advent and its networking aesthetics, post-production visibilities, and interactive dynamic in the realm of the Internet, and in contemporary media art.

In recent years, specifically since the start of the uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa eight years ago, the term “documentary” has become a name associated with the ubiquitous presence, online availability, and visibility of still and moving images that inhabit the region and are supposed to be shot, saved, recorded, witnessed, altered, and very much present in the nowness of the digital realm, and, accordingly, the instantaneity of geopolitical crisis. Looking at the networking structures of contemporary aesthetics in the visual arts, on the one hand, and their very “networked aesthetics” on the other, the boundary between there and here or here and there ceases to exist for an understanding of the documentary image that signifies a clearly hierarchical signification between the material “real” life in front of the camera and the animated lifelessness in front of the camera as a moving image.

The documentary image in moving images has emerged as a subjectivized biopolitical force of a new artistic public sphere that has fundamentally shaped a post-digital becoming of life-worlds and post-cinematic realms. One such example is visual artist and media theorist Laila Shereen Sakr’s work in the aftermath of the 2011 standoffs in which she juxtaposes popular culture and encultured animations with images of street documentary quality and timeliness that capture the present moment of events in Cairo. We see the iconic figure of Um Kalthoum, technicolored and incorporated into the documentary files of mobile images, overlooking the events while performing, thus acting as the angelic projection of collective memory. Um Kalthoum, the national icon of the mid twentieth century in the Arabic-speaking Middle East appears amongst superimpositions of animated figures within the sheer texture of the image’s materiality.

Future imaginaries in the Middle East and North Africa, which are signified through sci-fi elements and animation methods, testify as a time of real-virtual simultaneity, a coincidental structural framework in contemporary media art and archival cultures that are emerging in and through the experience of crisis. This impacts a political critique and aesthetic method, reconfiguring the landscape of the politics of aesthetics.

Beyond the plethora of studies that emerged after 2010/2011 and the many references to what has been termed the “Arab Spring,” the “Arab revolutions,” “the Twitter and Facebook revolutions,” media art and archives shift the conversation to speculative modes of real techniques of the visual and data; they juxtapose vernacular pop cultures, the starkness of states of emergency, and artistic practices. This conceptual shift has been attended by the post-insurrection crisis, which unfolds ad infinitum and inevitably references the wounded, the fragmented human body in the materialized realms of media art. The digital body thus has never been restricted to the spheres of an allegedly immaterial data, on the contrary, yet the conceptual shift to the virtual sphere re-configures structural chances and notions of the public realm.

The signification of the documentary image that depended upon the hierarchical object/subject split, on the difference between the spectator and the screen, the outsourcing of the producing infrastructure, and the editing of this piece of the real, which the documentary image represents, has eventually been replaced with a new form of immanent enactment. The latter attempts to transcend the finitude that the image of death and ruin of people and cultures in times of war eventually shows and signifies beyond the movement and sound of the actual image: stillness, death, and the freezing of time in the instant of death.

Narratives of new digitized archives that reconfigure questions of memory and performativity in terms of a collective intelligence of cultural memory have been disclosed in image collections and their harbouring institutions, which we have already witnessed through the establishment of organizations like Beirut’s Arab Image Foundation. A number of other artistic collectives have emerged in recent years in the Middle East and North Africa that employ the digitized archives of contemporary moments in time and the events of crisis (be it the crisis of migration to the north, the omnipresence of war throughout the region, or the political upheavals since 2011). The archive[1] has become a critical and astute medium of critiquing and visualizing a political control and sovereignty over life and death a “necropolitics”[2] that eventually becomes part of the very materiality of aesthetics. This is achieved by adopting a performatively co-optional role and function in the visual cultures of the region and its geopolitical enactment in the various technological alterations of the visible.

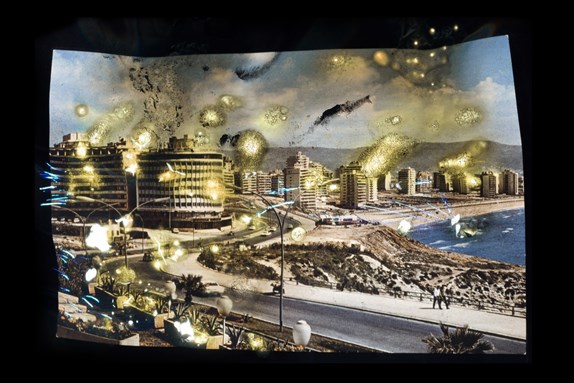

Such alterations through technologically induced operations become archives in their own right, in the new public spheres that have been developing across the Middle East and North Africa, and their very being as others, as new documentary othersof the contemporary moment of crisis is surfacing. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s Wonder Beirut (1997-2006) is one such example, in which the historical documentary image in the form of a postcard, iconic and “authentic” as it may seem, is digitally deconstructed and visually edited in order to make the memory of the war ultimately become part of the historicity of images. Hadjithomas and Joreige started taking images of the destruction of the civil war in Lebanon and found themselves confronted with solely nostalgic images / memories of pre-war Beirut that display the wholeness and well-preserved completeness of the pre-civil war years. Eventually, Hadjithomas and Joreige set off to alter the nostalgic found postcards and images and transform them into impure, flashy depictions. The postcard as an analogue medium of yearning journeys and news far away from home becoming the critical garish image embellished with pop art patterns. Thus, the animated, applicated destruction of the city becomes a material part of the nostalgic yearning for the past and the wholeness of the future.

The archive as a medium of that very materialized alterity in the techno-spheres of political lives is disclosed and embodies, at the same time re-conceptualizes, what Hito Steyerl has called the “poor image,” the user-generated and network-affected, online debris of the vulnerable and violent present, for instance. Steyerl suggests that the poor image is, in analogy to Fanonian thought, the “wretched of the screen.” In the Egyptian collective Mosireen’s archive, which is found online and has gathered massive numbers of mobile documentary images, the interface of the website suggests a coordinate system of digital choices and selected viewings.

However, its very existence in the deep time of the digital underbelly embodies a critique that is not just working on the same premises as the neoliberal commodification of culture it represents in its very “poverty” and accelerating quality. “The wretched of the screen,” is the circulating, latent, operational image that is radically present yet absent; it is the digital radical image that en-acts the events in their visibility.

The “re-presence” of the archival image as an operative of a form of digital media archaeology in the context of crisis and trauma in the region reflects the post-revolutionary realm of media technologies and cultures. Then there is time, and the question of time in the form of melancholic remains and indicators of the long durée of crisis in the region. Whereas Walter Benjamin’s notion of the “here and now” seems to reflect the nowness of catastrophic events, the time of the digitized archives alters the connecting conjunction “and” to a disjunctive “or”–as in Mosireen’s networked archives of the real world–that foregrounds the synchronicity of diachronic events and affects.

Crises and their augmented digital lives become the filmic and aesthetic practices of the contemporary that ruminate over the Lacanian “sinthome” of time and history, a “disjunctively being in time.” Rania Stephan’s experimental film, The Three Disappearances of Soad Hosni (2011), transforms the found footage assemblage of a national Middle Eastern actress icon, whose death is dealt with as suicide, into a materialization of traces and the becoming of symptoms without necessarily referencing the very sources and origins of the malaise of the subject. The speculation embedded in this timely disjunction encloses the spatial anonymity and networked origins and traces of the new images of the archive in cine-media cultures in the MENA.

Rania Stephan Three Disappearances of Soad Hosni (2011). Copyright the artist. Courtesy of the artist and Marfa' gallery.

It is no longer reproducibility that morphs the visual and time, or the visual and the aural, or the individual and the collective in times of crisis (the conjunction of Walter Benjamin’s “Jetztzeit”, the here and now) but rather an internally diffracted and diversified symptom signified through a “disjunctively being in time.” The speculation embedded in this timely disjunction encloses the spatial anonymity and networked origins and traces of the image and body space, archived traces that no longer signify an absence or loss, but rather a becoming of the very sinthome in Lacanian terms. Stephans’ work, which relies on footage from the Egyptian actress’s films, develops a kind of therapeutic quest for her life and death as a national icon on screen. Stephan configures the film persona and her appearance on screen as symptoms of a traumatic experience, national politics, and Hosni’s movement through the Egyptian cinematic history as a retracing of historical events and geopolitical crisis.

The multitude of digital experiments with the documentary material constitutes the very individuation of the artwork and its “impure aesthetics.” The desire towards new modes of existence and cultural belonging through the visual material provided by technical devices is not new, yet the reconfiguration of crisis as a) a form of assembling the new through networks and b) as the onto-epistemology of the documentary seems vital for a new take on the genre of “the documentary” as much as on archives and documentary images in the wild. Iraqi artist and filmmaker Jananne al Ani, for one, has exhibited aerial images, satellite images, of the Iraqi desert after the 1991 Gulf war that display abstraction and lunar shapes yet remain devoid of the human body in landscapes of war and military violence. Al Ani’s documentary cartographic images show the vividness of the surface of images, their material and molded shape while transmitting the beauty of abstracted empty landscapes and their geological secrets and traces beneath layers of sand and earth.

Considering the barrenness and omnipresence of the all-absorbing presence of images on personal devices, we might argue that our understanding of the documentary mode has been transformed from austere to unrestrained, and what becomes clear about the multiplicity and variety of artistic, primarily digital, productions is that there is a new desire for the modes of documentary existence and cultural belonging that are intrinsic to forms of engagement, embodiment, and future imaginings. In the age of wild media and rogue archives, we have moved on from an ethnographic “thick description” of other spaces and cultures as well as from the outsourced position of the participant observer to the desire in matter, the affective and excessive matter of the documentary image as the material subject and agent of crisis in its various medial convergences and interfaces. What we witness in the practices of documentary filmmakers is the recognition of distributed agency that is expanding, and it is the performativity of desire, the desire of the documentary image itself to finally become the “sinthome” of its geopolitical and capitalist economy. The documentary image and the artistic practices that work through documenting cultural narratives and histories create modes of existence and belonging that are imminent forms of complicity and enactment.

The Desire (to become, to make, to show) that is very often disguised as an approach, but does represent a desire to become and belong at the same time, sheds light on the interconnectivity between human actors and technology, or in other words: non-human actors, whilst upholding an often existentialist dimension and concern for life in civil societies and the struggle to survive under the rule of law.

The biopolitical implications that the documentary image engenders through the concomitancy of technology and human and environmental lives recall Giorgio Agamben’s approach to the interrelation of “subjective technologies and political techniques.” The filmic documentary radical image becomes an intrinsic figure of an alterity and heterogeneity-in-practice, a double-bind material economy of digital contemporaneity and disaster politics—the ambivalence and intricacies of not just being in time, but embodying a criticality through heterochronic features and immanent methods of becoming.

Thus, the contemporaneity of crisis as/through documentary images sets out to expand the reach of theories of a filmic materialization of perceptual processes (affect and cognition), theories that have already been thoroughly discussed in the context of the cinematic apparatus. Crisis and its accelerating, often documentary, impact on the world expands the sensorial reciprocity of the cinematic as an aesthetic materiality of film in addition to the epistemological functionalization of the time-based knowledge of images. The affective turn in film and digital media theory has led to a stronger linkage of the image space and the affective body of the filmic and (extra-filmic) subject.

[1] Cf. also for the discussion of archives in Middle Eastern film: Laura Marks, Hanan Al Cinema, 2015.

[2] Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, in: Public Culture 15, no.1 (2003), 11– 40; 11–12: “Hence, to kill or to allow to live constitute the limits of sovereignty, its fundamental attributes. To exercise sovereignty is to exercise control over mortality and to define life as the deployment and manifestation of power…under what practical conditions is the right to kill, to allow to live, or to expose to death exercised? Who is the subject of this right?”