[This article is part of a roundtable on the relationship between engineering, technopolitics, and the environment in the Middle East and North Africa. Click here to read the introduction and access links to all entries in the roundtable.]

In this essay, I introduce four Zionist water technoscientists who initially worked in Mandatory Palestine prior to 1948 and later in Israel after the establishment of the state. My aim is to use their stories as guides to answer the following questions: Can we speak of a coherent Zionist settler-colonial project that continued under two different regimes of government: imperial British rule and the Israeli state? In other words, should the establishment of the Israeli state change our understanding of the settler-colonial project? Or, does it merely signal a change in detail? If the latter, what are those details, and do they change in any fundamental ways the very settler-colonial project? How does the settler-colonial project preserve its coherence under different systems of governance and under different regimes of calculation?

I argue that, yes, indeed, we can speak of a coherent Zionist settler-colonial project.[1] But I also argue that its continuity cannot be taken for granted and is in need of explanation; it is neither necessary nor a foregone conclusion. The project’s ability to continue and to have coherence under different regimes of government lie in dynamic adjustments made to the very technologies of government that sustain it.[2] My aim is to demonstrate how important water technoscientists have been to the Zionist settler-colonial project and its continuity. Their importance is clear in at least three ways. First, they have been masterful agents of articulation who produced seemingly neutral technoscientific regimes of calculation that justified certain immigration and settlement policies in the service of the Zionist project. Second, they have also been instrumental in advocating for and building what I call Zionist infrastructures of elimination, infrastructures that erase indigenous natives and make the possibility of indigenous regeneration very difficult, if not impossible.[3] And, third, in technicizing the question of immigration and settlement through specific infrastructural approaches, technoscientists have been instrumental in stabilizing the settler-colonial project across different regimes of government, from imperial to statist forms.

While many of the technoscientists I discuss here were indeed certified engineers, a few were not (e.g., geologist Leo Picard). My use of the term technoscientists, as opposed to engineers, builds on attempts by science studies to destabilize the boundaries between science as an exclusively epistemological project and technology as its application. By extension, the strict boundaries between scientists and engineers that we often find in public discourse at universities, professional organizations, and the media need re-examination. As a matter of fact, in the context of Palestine, especially in the first half of the twentieth century, the very distinction between a Zionist scientist (interested in epistemology) and a Zionist engineer (interested in the construction of things) becomes meaningless. This is because both historical figures are often embodied by the same individual.[4]

In response to this roundtable, I focus on two episodes in which technoscientists played a major role in the Zionist settler-colonial project. First, I tell the story of how Zionist technoscientists under British imperial rule were able to conclude that water in Palestine was abundant by articulating a biblico-historical narrative with techno-rational discourses. Abundance was consequently articulated with the necessity, not plausibility or desirability, but the necessity of Jewish immigration and settlement in Palestine. I call this a geobiblical regime of calculation. This comes with its own infrastructural logic that is based on decentralized settlement and water provision. Second, I show how after the establishment of the state, technoscientists were able to shift emphasis to water scarcity. In turn, they actively articulated water scarcity with Ben-Gurion’s political philosophy of mamlakhtiyut, often translated as statism. This political philosophy imagined a strong, heavily centralized state apparatus to be necessary for Jewish national regeneration and state security. Some might call this “state-hydraulics,” i.e., the takeover of water governance by the state. But that framework usually conveys a deep state interest in supporting the hydrological needs of its populations, understood as citizens. Here, I call this a hydroinsecurity, read hydro-in-security, regime of calculation. I use the term to point to the necessary coupling of (or dialectic between) security and insecurity in settler states: the necessity of producing indigenous insecurity in the process of maintaining the security of the settler communities. The settler-colonial state, in other words, invests in securing its control over the territorial and hydrological resources by increasing the insecurities of the indigenous population.[5]

British Imperialism and Zionist Settler Colonialism: Turning Water into a Political Object in the Absorptive Capacity of Palestine

In 1922, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Winston Churchill, issued a White Paper in response to the Palestinian revolt of 1920 against British colonialism and the Zionist project of immigration and settlement. On the one hand, he rejected Palestinian demands to stop Jewish immigration and settlement because, he argued, Jewish immigrants to Palestine are there “as of right and not on the sufferance.” Such right was based on a biblical reading of history: it was to “rest upon ancient historic connection.” However, in the same White Paper, Churchill decided that immigration should be handled carefully, supposedly in order to protect the livelihood of the population of Palestine. To do that, the White Paper limited Jewish immigration within the “carrying capacity” of Palestine, which from then onwards would be assessed on an annual basis.

In any case, water was soon to become one of the most important elements in the calculation of the carrying capacity of Palestine, which soon became, fittingly, the “absorptive capacity” of Palestine. That is of course because of water’s importance to agriculture, which was central to Palestine’s capacity to absorb new immigrant-settlers. As a calculative strategy, the absorptive capacity of Palestine turned the political question of Jewish immigration into a technical-rational question of water’s availability. This certainly turned Zionist water technoscientists into essential actors in the calculative strategies of the settler-colonial project, a position they would maintain until the late-1980s and early-1990s.

In the following sections, I explore some of the ways these technoscientists participated in their capacities as technical agents of articulation: they helped sustain the coherence of the settler colonial project when styles of government shifted from an imperial encounter to a state form.

Technoscientists and the Geobiblical Regime of Calculation

The professional biographies of Leo Piccard and Walter Lowdermilk throw into sharp relief my main assertion in this piece: technoscientists are superb agents of articulation. Both were instrumental in constructing what I call a geobiblical narrative that articulated particular epistemologies of water with certain approaches to infrastructure and dominant ideologies and institutions of Jewish settlement.

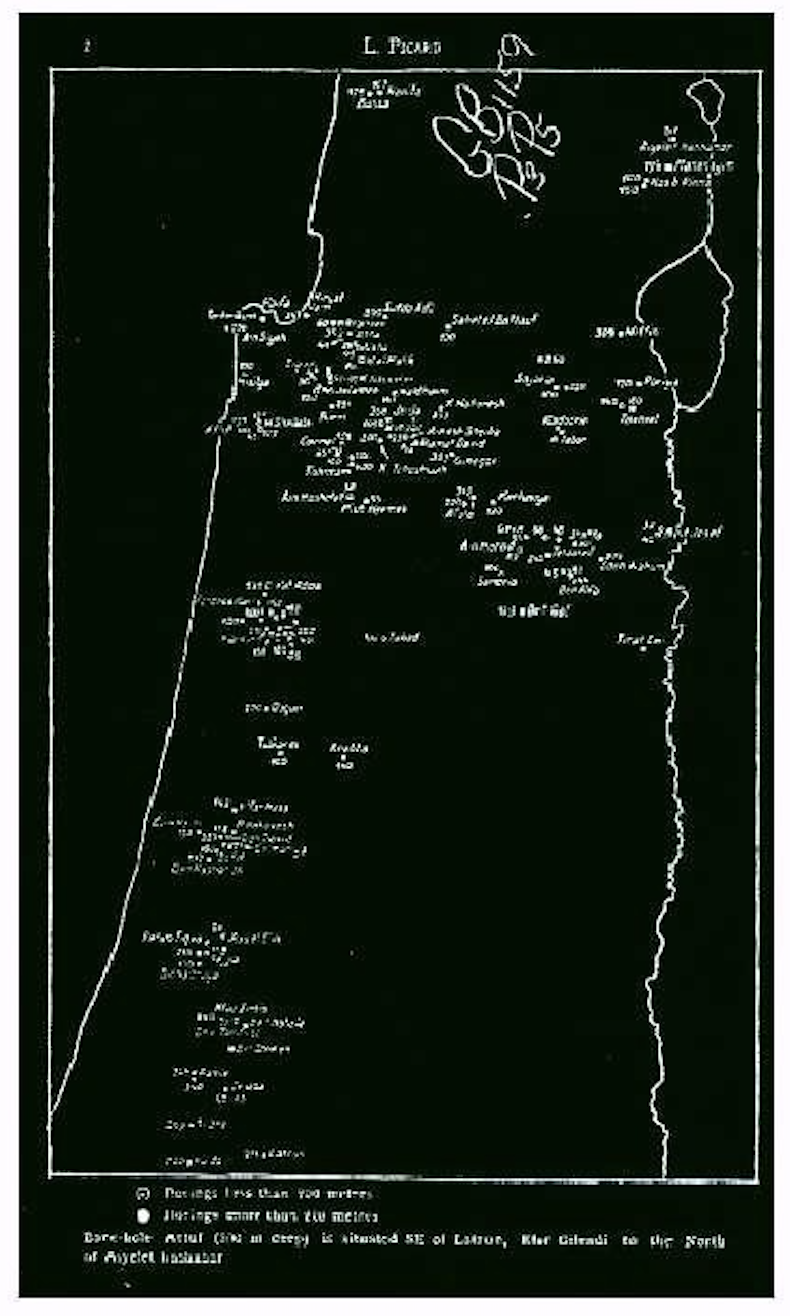

Leo Piccard was a geologist who settled in Palestine in the 1920s and was credited with establishing the geology department at the Hebrew University in 1926. His research on the groundwater aquifers of Palestine was important for legitimizing water abundance as “fact.” It was essential for turning water into a central element of the absorptive capacity of Palestine that technicized Jewish settlement.[8] More importantly though, his research on behalf of the Jewish Agency on Palestine’s groundwater aquifers and the presumed subterranean links among them in the mid-1930s led to a new framework for thinking about water. Instead of perceiving water in local and regional terms for the purposes of access and delivery, Piccard led the way to understanding it as a national-territorial hydrological system.[9] His focus on groundwater aquifers and the subterranean connections among them (fig. 1) were matched by the territorial settlement pattern of new settlers, a pattern that was later reflected in the Peel Commission’s Partition Plan in 1937. In a way, Piccard’s work naturalized both Zionist settlement patterns in the 1930s and 1940s and the presumptive boundaries of the Peel Commission.

Piccard’s map of groundwater aquifers in Palestine. (Author’s copy from the Zionist Archives in Jerusalem.) The author copied Piccard’s map from the Zionist Archives in Jerusalem in the late 1990s. Even though it is unclear, it should show the dots, each of which represents Piccard’s assumption of the presence of groundwater aquifers accessible through drilling.

With Piccard’s national-territorial hydrological approach, the initial infrastructural logic of Zionist settlement that focused on local and regional waterworks with multiple water companies was slowly but surely displaced. For example, the Mekorot water company was established in 1937 as a “national” company with contributions from the Histadrut, the Jewish Agency of Palestine, and the Jewish National Fund. In any case, the Peel Partition Plan left the suggested Jewish state with limited access to the Jordan River and no access to the Naqab desert, which was included in the presumed Palestinian state. That plan fit well with Piccard’s study of the groundwater hydrological system and settlers’ settlement patterns along the coast in Palestine (compare Piccard’s map in fig. 1 and the Peel Plan).

It was left to Walter Lowdermilk to reimagine and expand the hydrological system of Palestine by bringing into the calculative strategy a focus on surface water, especially the Jordan River. Lowdermilk was an American soil conservationist and Christian Zionist. He was hired as a consultant by the Jewish Agency in 1939 to study the soil of Palestine. His host in Palestine was Simcha Blass, a water engineer who is credited, along with the third prime minister of Israel, Levi Eshkol, with establishing Mekorot. Blass’ work in the Zionist water sector became a huge influence on Lowdermilk who ended up focusing on water resources instead.[10]

Using the infrastructural example of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the United States, Lowdermilk introduced a new possibility of diverting the Jordan River in the north to the Naqab desert in the south in order to make possible Jewish settlement throughout the territorial contiguity of Palestine.[11] His imagined infrastructure continued the work of Piccard by expanding on the hydrological unity of the proposed Jewish state to include the Jordan River and the Naqab Desert. In other words, he expanded the hydrological basis of the potential territorial state of Zionist settlers. As a matter of fact, Lowdermilk’s proposed project of bringing the Jordan River's waters to irrigate the Naqab became a central component in the UNSCOP negotiations over the partition of Palestine in 1946-7. Initially the partition plan of 1947, what is known as the minority plan, was based more or less along the Peel Commission and Piccard’s hydrological imaginary (with some disconnected land in the Naqab and access to the Dead Sea). However, the last version of the partition plan, voted on in the United Nations Security Council on 29 November 1947, included the whole of the Naqab desert in the Jewish settler state and was openly based on the Lowdermilk hydrological imaginary.

In collaboration with the American engineer James Hays, the Lowdermilk project became the Lowdermilk/Hays plan. In 1948, the Chair of the Commission on Palestine Survey, Emanuel Neumann, who played a major role in the partition negotiations, spoke of this openly: “those who had been responsible for working out the details of the United Nations partition plan, were familiar with the basic aspects of the Lowdermilk-Hays project and took it largely into account in drawing the boundaries of the new states. The Jewish State was awarded an area embracing the upper reaches of the Jordan in the north, the Huleh basin, the Sea of Galilee and its adjacent plains, the Emek, the Coastal Plain and much of the arid but irrigable land in the Negev.”[12] Not only did the Lowdermilk/Hays plan inform partition, it subsequently shaped the development of the water infrastructure in Israel during the 1950s and 1960s.[13]

But the content of their knowledge about water (e.g., abundance) was not the only or most important element in grounding the settler-colonial project. That extended to the methodologies that different technoscientists utilized in the production of that knowledge. For example, like every “good” geologist at the time, Piccard believed that assessments of water availability had to be based on empirical research and, more specifically, in the geological rock strata. Following the rock strata was a signal that as a geologist, and in contrast to geophysicists, he was still committed to a worldview of earth as a static system that changes slowly, if at all; at the time, geophysics saw a dynamic system (e.g., continental rift and tectonic plates) with change as a central component.[14]

In turn, a geological framework that sees earth as a static system and emphasizes the empirical over the theoretical easily articulated with a biblical-read-historical narrative of Palestine as the land of abundance. The view of Palestine’s water in a geologic framework was successfully articulated, at least in Zionist circles, with the biblical view of water as abundant. The argument that water was scarce in practice, for Piccard and the Jewish Agency, was, if at all, a failure of government. It was the failure of the British Mandate government to invest in finding the water to which both geology and Bible-as-history testify. This is what I call a geobiblical rendering of the environment, as we see in many writings of the period.

The same and probably more pointed geobiblical reading of Palestine as the land of abundance comes from Lowdermilk’s reading of the Bible-as-history. In his above-mentioned book, Lowdermilk makes two arguments. Palestine has abundant water resources (it was able to support millions more of the Israelites in the supposed biblical-archeological record) and a static environment—left alone, rainfall patterns would have been the same. Any negative change on the land was ascribed to the lack of industrious people. The Jews of the past turned, or at least preserved, Palestine as the land of milk and honey. However, those who replaced them lacked energy, industriousness, civility, appreciation of the land, and more. In essence, it was precisely because the land had been suffering due to the indigenous population of Palestine that the need to open Palestine to Jewish settlement and colonization became urgent. According to Lowdermilk, it was important for the rehabilitation of the land, the redemption of the Jewish people, and even the salvation of the indigenous Palestinian population who would benefit from the new enlightened settlers. What better mechanism to accomplish this than an infrastructural project that would deliver water from the Jordan River in the north to the Naqab desert in the south?

Zionist arguments of water’s abundance legitimized an open Jewish immigration and settlement policy. However, abundance without a clear sense of a unified geo-hydrological system kept the water policy of the Zionists extremely decentralized within a vaguely defined Jewish National Home. That changed after the mid-1930s when the prospect of partitioning Palestine became a reality. The geo-hydrological system of Palestine that Piccard introduced legitimized reconceptualizing the Jewish national home in terms of a nation-state. However, his limited conceptualization of the hydrological system of Palestine as geological (meaning focused on groundwater resources) limited the territorial prospects of the new imagined settler state. It was left to Lowdermilk to expand that system to include surface water and propose an infrastructural project that diverts the Jordan River to the Naqab Desert, at once serving the Zionist expansion of the imagined territorial state and spaces of settlement.

Technoscientists and the Hydroinsecurity Regime of Calculation

The Lowdermilk/Hays plan of 1948 became the basis for a number of iterations of the Israeli master water plans between 1950 and 1957. This culminated in the construction of the Israeli National Water Carrier (NWC), which began its diversion of the Jordan River in 1964. The two technoscientists most credited with organizing the water sector in Israel were Simcha Blass and Aaron Wiener. Both Blass and Wiener were water engineers whose professional lives spanned the periods of pre- and post-1948 when they became central figures in water policy during the 1950s. Blass went on to become a world-renowned water engineer after inventing drip irrigation in the 1960s. Wiener’s career, as a central figure in Israeli water policy circles, lasted until his retirement in 1977. Blass headed the water department of the ministry of agriculture in the new settler state while Wiener became the chief engineer of Mekorot.

This institutional difference and the professional biographies of each shaped the similarities they shared and the differences that separated them. It is important to note that the conflicts between the two were resolved by building a new institution in 1952, Tahal water planning company, with Blass as its director and Wiener as his deputy. A major conflict between the two centered on the estimate of the annual water potential of Israel: Blass was committed to a narrative of water abundance (more than 3,000 million cubic meters per year, mcmy) and Wiener, in turn, insisted that water was scarce (between 1,500-2,000 mcmy). This conflict resulted in Blass’ resignation in late-1953 and Wiener taking over in his place until 1977.

While both agreed that the NWC should be prioritized to serve new settlements in the Naqab desert, they differed on its place in national water policy. Blass argued that the NWC should be a standalone project, not connected to other sources, like groundwater. Wiener, on the other hand, believed it should become the central infrastructure of the state through which all water, even the rain, is managed (ground- or surface-water). In the end, Wiener won the argument and the NWC became the central infrastructure for water management.

Blass’s defeat and Wiener’s rise to the top of water policy institutions in 1953 was a sign of a more fundamental shift in the very regimes of calculation that underwrote the new statist governmental rationality of the Zionist settler-colonial project. I describe this shift as one from a geobiblical regime of calculation to one based on discourses of hydroinsecurity. Wiener and those I described previously as the “new engineers” were able to articulate so much about water with Ben-Gurion’s political philosophy of mamlakhtiyut. For Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, the state was central not only as representative of Israelis, and Jews more broadly, but as their very source of identification.In the process, Ben-Gurion saw the state as coextensive with Jewish subjectivity. In order to protect the state from enemies outside and inside, all forms of representation of pre-state Jews needed to be resolved in the image of the state. For that reason, Ben-Gurion waged his great war of centralization: labor exchanges, education, army, health care, and more. For him, centralization of state institutions was a matter of security. Water became extremely important in the project of centralization during the first few years of the state and remained as important until the 1980s.

Wiener’s epistemological, institutional, and infrastructural approaches found home in mamlakhtiyut. In epistemological terms, Wiener insisted on utilizing an empirical as opposed to Blass’s theoretical approach to water availability. Blass used a deductivist approach in which the water potential of groundwater aquifers depends on mathematical calculations of annual rainfall and rate of percolation. He estimated that annual potential at a minimum of three thousand mcmy, and probably approaching four thousand mcmy. Wiener on the other hand directed the sinking of more than two hundred exploratory wells to empirically determine the state’s water potential. He estimated that to be about 1,500-2,000 mcmy. This “scarcity” of water became an “obsession” of Wiener to the degree that many of the actors working during the 1950s acknowledged that in my interviews. Even Wiener himself acknowledged and smiled at the fact that others describe it as an obsession. His argument: “I was right."[15]

Water’s scarcity was framed from the very beginning as a threat to the state's security and to the security of Jewish immigration and the settler-colonial project—especially to the settlement of the Negev and border towns. True to the spirit of Ben-Gurion’s mamlakhtiyut, the response to water scarcity was the centralization of both water policy apparatus and infrastructure. A series of legal instruments were enacted from 1955 onwards that culminated in the Water Law of 1959. One of the main effects of that law is the creation of the office of the Water Commissioner to whom Mekorot and Tahal would report, and who would direct all water abstractions, delivery, and licensing. This centralization of management institutions was matched only by the centralization of the water infrastructure through the National Water Carrier. The NWC was not limited to conveying water from the Jordan River to the Naqab (the position of Blass), but to handling all the waters of the state. Basically, all waters of the state had to go through the NWC.

This naturalization of both the in/security of the state and the centralization of its water policy apparatus and infrastructure were important for the discursive and material articulation of water policy with mamlakhtiyut. It naturalized a hawkish geopolitical position for the diversion of the Jordan River over the objections of other riparian states. It also naturalized Ben-Gurion’s strong position against some of his historical allies like the Kibbutzim movement, which was strongly against state intervention in water policy and management.

The biographies of these two engineers, their professional training, methodologies, and political frameworks, became important elements of articulation; they became elements of the competing infrastructural logics of the time. Aaron Wiener succeeded, since his notions of water infrastructures, water law, epistemological methods, and water governance were successfully articulated with Ben-Gurion’s political strategy of mamlakhtiyut. Wiener’s understanding of the centrality of NWC to water matched Ben-Gurion’s understanding of the centrality of state institutions for a new Jewish subjectivity that is not only represented by the state, but that gets its understanding of self from those very institutions.

Conclusion

I would like to return to one of my main arguments here. Technoscientists have been instrumental in sustaining the settler-colonial project by dynamically refiguring how and what to know about water, how and what to know about infrastructure, and how and what to know about ideologies and institutions of settlement. They served as amazingly creative agents of articulation: they “knew,” they “built,” and they “governed.” Their infrastructural approaches sustained the settler-colonial project under British imperialism, initially through technicizing and depoliticizing immigration and settlement. They also sustained it by producing a discourse of abundance that legitimized flexible, locally and regionally based infrastructural responses to the needs of diverse settler communities. Then, when those approaches were insufficient and became a threat to the state-directed settler project, technoscientists delivered in epistemology (empirical methods and a focus on scarcity), in infrastructural approaches (the material centralization of resources in one infrastructural project), and ideologies/institutions (the production of insecurity and vulnerability, as well as a centralized administrative apparatus).

While a geobiblical regime of calculation was deployed to enhance the settler-colonial project under British imperialism, a hydroinsecurity regime of calculation was articulated with a statist form of governance.

This shows that settler colonialism, at least in this case, utilizes an economy of power that, while often physically violent (removal and murder of the native), is also infrastructurally violent (arresting the native’s right to infrastructure). One can only hope that figuring out what sustains the settler-colonial project from one form of government to the next might help us figure out how to escape its utter control. The hope is real, especially when we already know that the continuity of settler colonialism is neither guaranteed nor necessary.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my thanks to the editors of the special roundtable for inviting me to contribute and for their continued patience and support. Thank you to Jane Collins, Saul Halfon, and Gregg Mitman who commented on an earlier draft. Special thanks are also due to Gabi Kirk and Rafi Arefin for reviewing and commenting on an earlier version. I also extend my special appreciation to Danya Al-Saleh who not only skillfully reviewed and commented on the piece, but did it with such grace.

[1] In the 1960s and 1970s, Palestinians used settler colonialism as an organizing principle that often framed the very dynamics of liberation (see for example, Fayez Sayegh and the great number of political platforms of the Palestinian movement since its inception in the 1960s). Many recent studies of settler colonialism, however, brought a sustained academic attention to Palestine. The suitability of using the settler-colonial framework to understand and intervene in the Palestinian context, however, is not a settled academic debate. For example, in a recent excellent article, Rana Barakat suggests that a better fit would be to place Palestine within indigenous studies. See Rana Barakat, “Writing/Righting Palestine Studies: Settler Colonialism, Indigenous Sovereignty and Resisting the Ghost(s) of History,” Settler Colonial Studies 8, no. 3 (2017): 349-363. Omar Jabary Salamanca, Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie and Sobhi Samour, “Past is present: Settler colonialism in Palestine,” Settler Colonialism 2, no.1 (2012): 1-8; Fayez A. Sayegh, Zionist Colonialism in Palestine. Beirut, Lebanon: Research Center, Palestine Liberation Organization. Lorenzo Veracini, “What can settler colonial studies offer to an interpretation of the conflict in Israel-Palestine,” Settler Colonial Studies 3, no.3 (2015): 268-271; Patrick Wolfe, “Purchase by Other Means: The Palestinian Nakba and Zionism’s Conquest of Economics,” Settler Colonial Studies 2, no.1 (2012): 133–71.

[2] In the particular sense here, I understand technologies of government to result from articulating technoscientific views of nature with approaches to infrastructure and political ideologies and institutions, all in order to successfully direct the “conduct of individuals or groups.” See Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 4 (1982): 790, 794.

[3] For an example of the growing literature on infrastructural politics in Palestine and its relationship with settler colonialism, see Muna Dajani, “Thirsty water carriers: The production of uneven waterscapes in Sahl al-Battuf,” Contemporary Levant 5, no.2 (2020): 97-112; Sophia Stamatopoulou-Robbins, “Failure to build: Sewage and the choppy temporality of infrastructure in Palestine,” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, (March 2020); Leena Dallasheh, “Troubled Waters: Citizenship and Colonial Zionism in Nazareth,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 47, no.3 (2015): 467-487; and Amahl Bishara, Nidal Al-Azraq, Shatha Alazzah, and John L. Durrant, “The Multifaceted Outcomes of Community-Engaged Water Quality Management in a Palestinian Refugee Camp,” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, (May 2020).

[4] Derek Penslar, who uses the term “Zionist technocracy” to depict Zionist experts in pre-1918 Palestine, adopts a somewhat similar approach to engineering. See Derek Penslar (1991), Zionism and Technocracy: The Engineering of Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 1870-1918. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

[5] For a great example of how the same infrastructures of elimination produce the insecurities of Palestinian farmers in Israel, see Dajani, “Thirsty water carriers,” 97-112.

[6] For an excellent discussion of the history and implications of the general concept of “carrying capacity,” see Nathan Sayre, “The genesis, history, and limits of carrying capacity,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98, no. 1 (2008): 120-134.

[7] For example, in an argument that was repeated many times during the Peel Commission’s hearings, Arthur Ruppin wrote in 1934 that for each family in agriculture, Palestine could support two to three hundred families of settlers. So, the challenge is to find water for farmers. Arthur Rupin (1934), The Jews in the Modern World. Kessinger Publishing, LLC.

[8] Samer Alatout, “Bringing abundance into environmental politics: Constructing a Zionist network of water abundance, immigration, and colonization,” Social Studies of Science 39, no.3 (2009): 363-394.

[9] Leo Piccard, On the geology of the central coastal plain. (Hebrew University, 1936); Piccard, Groundwater in Palestine (Hebrew University, 1940).

[10] Many of my interviewees in the 1990s credited Blass with convincing Lowdermilk that water, not soil, was the most important element in Palestine’s geography and rehabilitation, and that water was indeed abundant in Palestine.

[11] Walter Lowdermilk, Palestine, Land of Promise (Harper & bros, 1944).

[12] Walter Lowdermilk, Palestine, Land of Promise (Harper & bros, 1944). Many argue that Herzl introduced this idea in his book, Altneuland. This is true, but it is historically naive to imagine that there is a straight line that connects Herzl’s imaginary project and that of Lowdermilk’s.

[13] Hays, T.V.A. on the Jordan: proposals for irrigation and hydro-electric development in Palestine. (Washington, DC: Commission on Palestine Surveys, 1948): xv-xvi.

[14] See Peter Bowler’s work for a great history of the emergence of geophysics and its conflicts with geology. Peter Bowler, The Earth Encompassed: A History of the Environmental Sciences (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1992).

[15] Interview with author, 6 September 1998.

[16] Dajani, “Thirsty water carriers,” 97-112; Stamatopoulou-Robbins, “Failure to build;” Dallasheh, “Troubled Waters,” 467-487; Alberto Corsín Jiménez, “The Right to Infrastructure: A Prototype for Open Source Urbanism,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32, no.2 (2014): 342-362.