Nicholas Mangialardi, “Excavating Musical Heritage in Modern Egypt,” Arab Studies Journal XXXI, no. 1-2 (2023).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this article?

Nicholas Mangialardi (NM): My article, “Excavating Musical Heritage in Modern Egypt,” developed out of research I was doing on Egyptian singers of the mid-twentieth century. I was examining how the Egyptian public talked about popular singers but also who/what informed how they talked. Much of the information Egyptians consumed about music through different media—magazines, books, radio programs—was produced by state officials, teachers, and critics who formed a distinct social group. It seemed critical to understand this network that was shaping, or trying to shape, public taste around music. Who were they? Why did they advocate for certain musics and condemn others? How did they come to label some songs “artifacts deserving preservation” while others were “distortions of our heritage”?

I also wanted to consider how this network of experts not only invoked ideas of music “heritage” (turath) but took part in creating it. During the 1950s and 1960s, there was a burst of songbook publications, anthologies of lyrics and notated melodies aimed at collecting the nation’s musical past. I had questions about the material aspects of these books, how they circulated, how they displayed and made tangible a music culture that relied largely on oral transmission up to that point. I came across copies of these books while living in Cairo, but I found many more outside of Egypt, which prompted me to look into the kind of work these anthologies and their makers were doing.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the article address?

NM: The article focuses on a constellation of Egyptian officials, educators, and experts who were influential in the music field from roughly the 1950s through the 1970s. I discuss their efforts to preserve Egypt’s musical heritage. But I was mainly interested in what their preservation project might tell us about the cultural elites themselves and how they used music to maintain their status during a time of major social change in the country. I analyze how these experts framed Egyptian music as endangered artifacts that only their modern expertise could save. They gathered these artifacts (songs) in new anthologies, transcribing the lyrics and melodies. Their project leaned heavily on notions of a “lost heritage,” which in fact had much in common with earlier traditions of collecting musical knowledge in song anthologies. This part of the paper resonates with recent work by Jonathan Glasser, Carl Davila, and other scholars of North Africa exploring songbooks and material aspects of musical heritage.

J: How does this article connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

NM: My research has focused on Egyptian music and popular culture in the mid-twentieth century, so this article is closely related. My previous projects, though, have centered more on music makers (singers and song-poets) and the listening public. This article foregrounds a different group, the state-affiliated experts who were working to curate a cultural heritage for the public. So while I discuss music, I am mainly interested in examining this social stratum of middle-class professionals, known as the effendiya, and how they changed over time.

J: Who do you hope will read this article, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

NM: The article brings together a range of sources and perspectives from history, heritage studies, ethnomusicology, and other fields, so I hope it will be of interest to scholars both in and outside of Middle East studies. It may be especially relevant to those doing research on the effendiya and their place in cultural production. Scholars have often discussed the effendiya’s impact during the first half of the twentieth century, but less has been written about their transition into the Nasser era, when new sociopolitical regimes compromised their status. Additionally, I hope the article may provide some insights for practicing musicians curious about the repertoires they perform today, how songs were transcribed and transmitted, and how music was modified in the process.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

NM: Like this article, my other research projects focus on modern Egypt and relationships between popular and official culture. One of these is a book project on the singer Abd al-Halim Hafiz, which explores his live performances and collaborative work with poets. Another project looks at Egypt’s cultural connections with Japan during the mid-twentieth century. This period is often studied through the lens of Egyptian nationalism or pan-Arabism. Yet, the Japanese archives I have been working in over the last few years reveal a vibrant era of exchange between these far ends of Asia in the fields of music, film, and literature.

Excerpt from the article (from pp. 6–8, 14–16)

In 1957, the Egyptian music scholar Mahmud al-Hifni published an article in al-Hilal magazine calling for the safeguarding of Arab musical heritage, particularly folk songs:

Folk songs are no less valuable than the excavated ancient artifacts that unite parts of a nation’s history. Furthermore, they are a solid foundation for scientific works, a bountiful treasure trove from which an artist can draw inspiration and creativity, songs that can be documented for the nation and eternalized with its artifacts. Arab countries would do well to attend to folk songs in their various styles, and to collect, systematize, and purify them.

Al-Hifni was a prominent music official, a member of the Higher Music Committee, founder of the state-sponsored Institute of Music Theater, and an icon of Egypt’s music establishment. His interests in national history and “scientific works” were typical of the country’s cultural elites at the time. But the language that he used to describe the preservation of musical heritage was new, one that framed songs as relics to be unearthed, collected, and displayed to show national progress. This peculiar parlance of music-as-artifact became ubiquitous among Egyptian music reformists during the 1950s, when discussions of national identity often invoked heritage. But why did the artifact, as a recurring trope, gain such currency in discourse about Egyptian music? What prompted the turn to this terminology? And what might the terms tell us about those who used them?

This article investigates the music field in mid-twentieth-century Egypt, focusing on the activities of cultural elites like Mahmud al-Hifni. It highlights how they came to describe the musical past as artifacts that, if lost, would deprive Egyptians of an “authentic” foundation upon which they were to build their modern present. Central to elites’ project of “saving” Egyptian musical heritage were songbooks, collections of lyrics and notated melodies. As I show, between midcentury and the late 1970s, local music reformists embarked on a new project of gathering Egypt’s folk and classical repertoires for publication in anthologies. This article examines two songbook series that appeared in this period. It combines recent scholarship from Middle East studies, ethnomusicology, and heritage studies to analyze how these books’ editors crafted a new discourse around musical decay, preservation, and Egyptian identity. I argue that songbooks, as material objects, helped give physical form to this discourse. Ultimately, I show that elites used songbooks to redraw Egypt’s modern image and to navigate various cultural, political, and economic changes that threatened their social status.

These elites were conservatory teachers, music scholars, administrators at state-run Egyptian radio, women and men connected to the music establishment. Since the nineteenth century, this group—along with other educated, middle-class professionals—had made up a social stratum known as the effendiya. Scholarship on modern Egypt has discussed the central role they played in shaping national culture during the interwar period. Yet comparatively little work has focused on the effendiya’s transition into the post-1952 era, when new sociopolitical regimes came to compromise their reformist project. Egypt’s military defeats in the 1960s, coupled with new consumerist lifestyles in the 1970s, fostered disillusionment with effendi ideology and state-sanctioned models of “culture.” Many whose status and livelihoods were tied to work in state institutions sought to reassert their authority as arbiters of “correct” modernity during this period. While the term “effendiya” vanished after midcentury, the group and its discourse endured in ways that remain understudied. Examining their lasting influence in Egypt allows us to see how effendi culture adapted and reproduced itself over time.

[...]

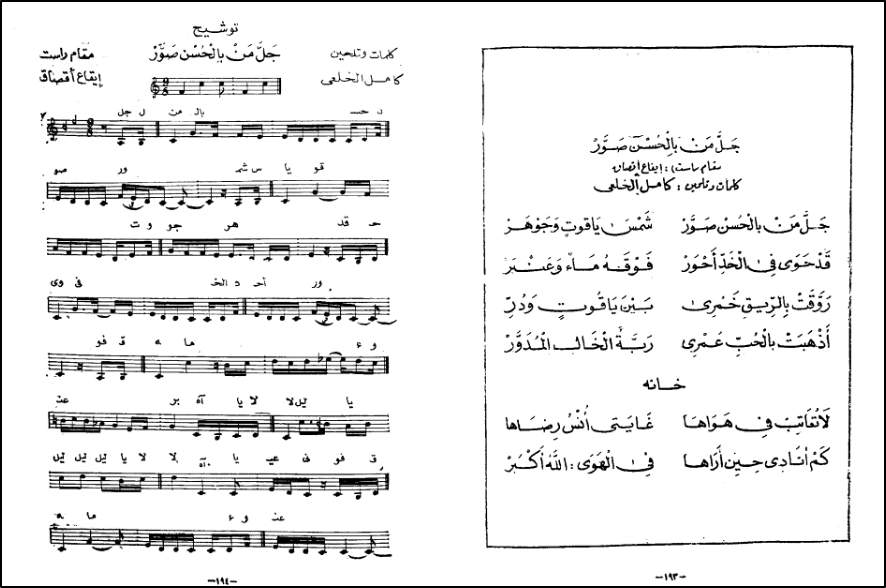

In 1958, the Egyptian state’s Higher Music Committee published the first volume of Turathuna al-Musiqi (Our Musical Heritage), a two-hundred-page anthology containing lyrics and notated scores for fifty adwar (sing. dawr). The dawr was an Egyptian vocal form of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries featuring both precomposed melodies and improvised sections. Subsequent volumes contained adwar as well as muwashshahat (sing. muwashshah), an earlier style of strophic song. Egyptian music experts considered these the most refined forms in the turath. They frequently described them as “analogous to classical songs in Western music.” The editors of Our Musical Heritage sought to collect and transcribe this repertoire, most of which existed only in oral form. Ibrahim Shafiq, a musician and educator, oversaw a team of scribes who diligently transferred melodies and lyrics to paper (fig. 1). The prefaces and chapters on Arab musical history were the work of Mahmud al-Hifni and Ahmad Shafiq Abu ‘Awf, Chair of the state’s Higher Music Committee (al-Lajna al-Musiqiyya al-‘Ulya).

The preface to the first volume laid out the editors’ goals, explaining their aim to “gather the scattered fragments of our old heritage” (shatat turathina al-qadim). After publishing the first volume of songs, they planned to “document the rest of the adwar that were popular and sung by all classes in Egypt.” Then they would work on collecting songs “that have not yet been documented and that one fears may go extinct.” They framed their songbook as contributing generally to Egypt’s modern cultural renaissance, pointing out that “no civilization has been built without first reviving the treasures of its old heritage.” This heritage would be “a foundation on which the nation’s civilization (hadarat al-umma) will be established.”

Figure 1: Score and lyrical text from Our Musical Heritage, Vol. III, 1963.

The preface to the second volume provided more details on the preservation process and difficulties the editors faced in finishing the book. They spoke again of gathering “scattered fragments of the heritage from culture bearers,” who provided “invaluable treasures of adwar and muwashshahat.” After the collection phase, the editors systematized songs in a “special archive.” But upon review of its contents, they realized that “many long years, perhaps more than a lifetime, are needed for this work to be complete, to document our musical heritage since the Arabs’ earliest history.”

By the time the fourth volume of Our Musical Heritage appeared (around 1963), the editors were estimating that they would produce an additional thirty volumes of “all of the Arab songs we could obtain.” But in fact, the fourth volume was the last they would publish for the old repertoires. In its preface, they explained again that they were hastening to salvage the turath as the elderly culture bearers (hafaza) with whom they were working could pass away at any moment. To lose even one of them, they warned, would be to “immediately lose a national heritage that could significantly clarify our understanding of an important branch of our civilization.” With these words, they reiterated the urgency of their project, despite not publishing another volume in the series. Ibrahim Shafiq, who handled transcriptions, passed away before the fourth volume went to press, perhaps leaving a difficult gap to fill. Other factors contributing to the series’ abrupt end remain unclear.

What is clear is that the editors portrayed Our Musical Heritage as a long-term project. It would require select specialists to collect, archive, and transcribe over many years, ensuring their employment and livelihood. It is also clear that a particular imagery was crucial to this project, notably the “scattered fragments of heritage” that editors often described. Fragments suggest that there was once a complete whole—the heritage—that had decayed and dispersed. The notion of restoring “our” past resonated with the sociopolitical context. The image of a reunited Arab region found its musical parallel in the trope of reassembling the tattered remains of the turath. Yet the remains in Our Musical Heritage were not only old repertoire but also pieces by recent composers and even the editors themselves. Thus, as much as the Higher Music Committee was collecting heritage, it was also creating its contents.