[This article is part of a bouquet developed by the Jadaliyya Environment and Palestine Page editors to highlight the work of critical mapping initiatives and research on the role of mapping spaces in Palestine, Lebanon, and across the region. The authors highlight not only their own work and its methodologies, but also discuss how they hope it contributes to our larger understanding of space and popular conversations of the spaces we inhabit and study. Read the rest of the articles featured in this bouquet linked at the bottom.]

Tell us about your project. What times, places, and topics does your work cover?

My research concerns mapping and counter-mapping in Palestine, from British and Zionist (later Israeli) mapping to Palestinian and anti-Zionist counter-mapping. I have two main objectives in my work: to analyze the relationship of mapping and power in (and of) Palestine; and to assess the potential of counter-mapping as part of a project of decolonization.

The Palestinian condition is such that any map is treated by Palestinians as a dubious object, capable of deceit. Maps represent more than just a physical image of place. They possess agency and should be read as texts just like paintings, theatre, film, television, and music; they speak of the world, disclosing and realising manifold spatial relations.[1] It follows, then, that a range of approaches are needed to make sense of maps. My work, as a policy fellow at Al-Shabaka; the Palestinian Policy Network, as an artist and filmmaker, and currently as a doctoral candidate at Newcastle University, has been to interrogate the possibilities and limitations of cartography in the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea between 1870 and 1967. I begin in 1870 because the first large-scale survey of this region was produced by the British-led Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) between 1871-1877. The PEF produced by far the most precise and technologically sophisticated maps of the region to that point and paved the way for the British to assume colonial control over Palestine during the First World War, fifty years later. I stop at the Naksa of 1967 (the “setback,” or Six Day War as it’s known outside of Palestine) and the extension of the Israeli occupation to the entirety of historic Palestine as well as the Syrian Golan and the Egyptian Sinai.

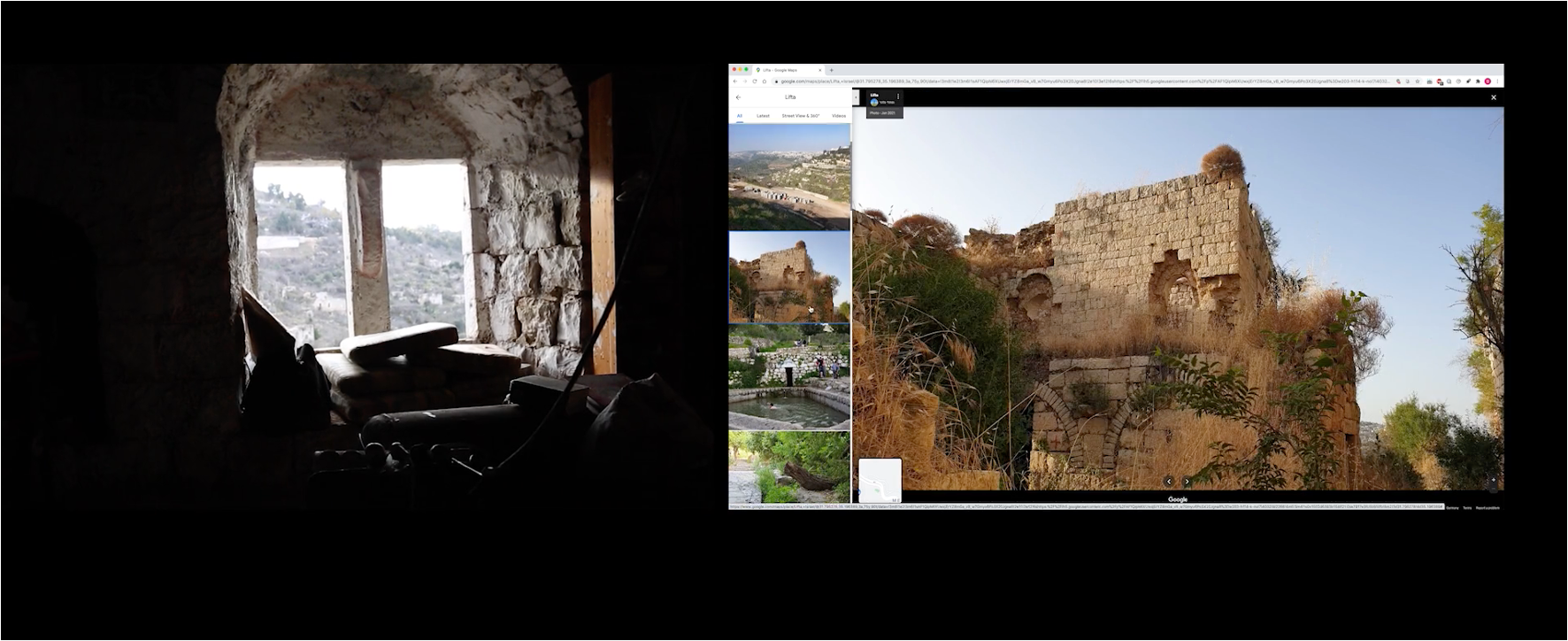

Simultaneously, I analyze (and produce) counter-cartographies of Palestine. Often termed “counter-maps,” these are alternative maps which attempt to recognize the past, critique the present and (re)imagine the future. As such, they are not bound by a timeframe. I include “traditional” and digital maps as well oral or memory maps, literature and poetry, tatreez (Palestinian embroidery) and visual and performance art. The nature of this work means that I have combined traditional approaches such as archival research with the deliberate subversion of colonial artifacts. This includes my own counter-mapping efforts through poetry, visual art, and documentary film – such as my 2021 experimental short, The Place That is Ours, co-directed with Dorothy Allen-Pickard (figure 1).

Figure 1 Still from The Place that is Ours (copyright Dorothy Allen-Pickard) 2021

The ongoing genocide in Gaza has, in different ways, transformed the goals of my research, not least since many of the geographies depicted in historical maps of Gaza have been annihilated. But it has also called the specificity of decolonization in Palestine into question, because discourses around what constitutes decolonization in Palestine have irrevocably altered since October 2023.[2] Just as I seek to interrogate the archive – the ways it evades and conceals – so too have I found that my own research has become an archive of sorts: a survey of a landscape which has since been hit by a devastating earthquake. Making sense of this research, both the maps and the contextual frames that surround them, and asking what value (if any) they have is a painful preoccupation. These reflections are intended to contribute to a broader, more urgent, conversation around the politics of mapping Palestine and its role in the work of liberation in this current moment, when the very existence of Gaza is under threat.

How did you come to develop your project? What sources and analytics did you draw upon?

My interest in maps was sparked in 2017 when I used the iNakba app (since renamed iReturn) developed by Israeli anti-Zionist organisation Zochrot to find my destroyed village in the Tiberius region. The app’s interactive map has pins in the locations of 600 Palestinian villages destroyed in the Nakba of 1947-48 with otherwise obscure Google Maps and Waze coordinates. It also includes demographic information on each village (for instance settlement before and after 1948; what military operation, if any, destroyed it, and so on) in Hebrew, Arabic, and English – information synthesised from Walid Khalidi’s 1992 seminal work All that Remains.[3] I used the only image the app had–a grainy picture of the landscape with rolling hills and palm trees–to check we were in the right place (figure 2). The land did not lie, even after seven decades.

Figure 2 Photograph of my destroyed village on the app and in reality. Copyright Dorothy Allen-Pickard

In the years since, I have contemplated the clandestine cartographic practices I had to resort to in order to re-discover this place. Israeli maps deliberately obfuscate, omit, and ignore Palestinian localities, both populated and depopulated. Just as the Israeli state has been built on the ruins of Palestinian villages, towns, and cities, the Israeli map has been drawn to negate any Palestinian presence.[4] A map is well-suited for this task. The “duplicity” of maps, what critical cartographer J.B Harley calls their “slipperiness,” is the essence of cartographic representation.[5] This is in large part because mapmakers were, and in many ways, still are, presumed to be engaged in an “objective” or “scientific” project of knowledge creation.[6] From this perspective, maps are perfect, scaled representations of the world, based upon unbiased factual information and accurate measurements.[7] Scientific positivism has created the perception that maps are detached, neutral, and above all, accurate graphic representations of space.

But how does empiricism (and its discontents) apply to Palestine as a site of contemporary colonialism, where indigenous land is confiscated and contested, where any map is out of date almost as soon as it is issued, and where the map acts as a prophecy for colonial intent? Most significantly, in what ways does debunking cartographic myths act as an important case for any designs on material change towards a decolonized world? These questions are the backbone of my work. My hope is that this research produces new knowledge on historical and contemporary practices of mapping in Palestine and will make conceptual and empirical contributions to debates in critical cartography, settler colonialism and decolonization.

Can you tell us a bit about your methodology? What do you include in your maps and what do you leave out? Why? How do you see your methodological choices in connection with analytic and political questions?

The archive features prominently in my research; in many ways it acts as my point of departure, not because of what it contains, but because of what it does not. I have carried out research in eight archives across the UK and US including state, public, university, and personal collections and have found many overlaps, contradictions, and silences. But most maps of Palestine (along with their ephemera – explanatory notes, special volumes, sketches, registers, census data, field guides etc.) are held in archives broadly inaccessible to Palestinians. Whether in the colonial archives of London, New York, Washington DC, Tel Aviv, or Jerusalem, Palestinians have limited access to large parts of the history of their land and people, particularly as seen through the colonizer’s eyes.

The importance of archiving cannot be overstated, as Jaques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz remind us: “There is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory. Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation.”[8] How can Palestinians understand their relationship to the land and imagine return without full access to the archive?

This is not unique to Palestinians. Indigenous peoples rarely have access to or exercise power over state archives, spaces often filled with documents and histories that instrumentalize the past to ensure settler presents and futures. Despite this marginalization of indigenous people and their relegation to a spectral presence in archival spaces, there has been a recent surge in the exploration and reclamation of archiving in indigenous, especially Palestinian, movements, many of these in the form of counter-cartographies. This might be understood as a reaction to the condition of exile. Beshara Doumani offers this interpretation: “I mention the attraction of archiving the present, not just the past, because Palestinians are still incapable of stopping the continued and accelerating erasure of the two greatest archives of all: the physical landscape, and the bonds of daily life that constitute an organic social formation.”[9]

It is perhaps for this reason that I find myself perennially drawn to the archive. The lacunae of the archive call for its subversion and reclamation. The archive has become a springboard for counter-mapping and alternative imaginaries. Saidiya Hartman, through her revolutionary “critical fabulations,” summarises this elegantly: “every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limit it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor.”[10]

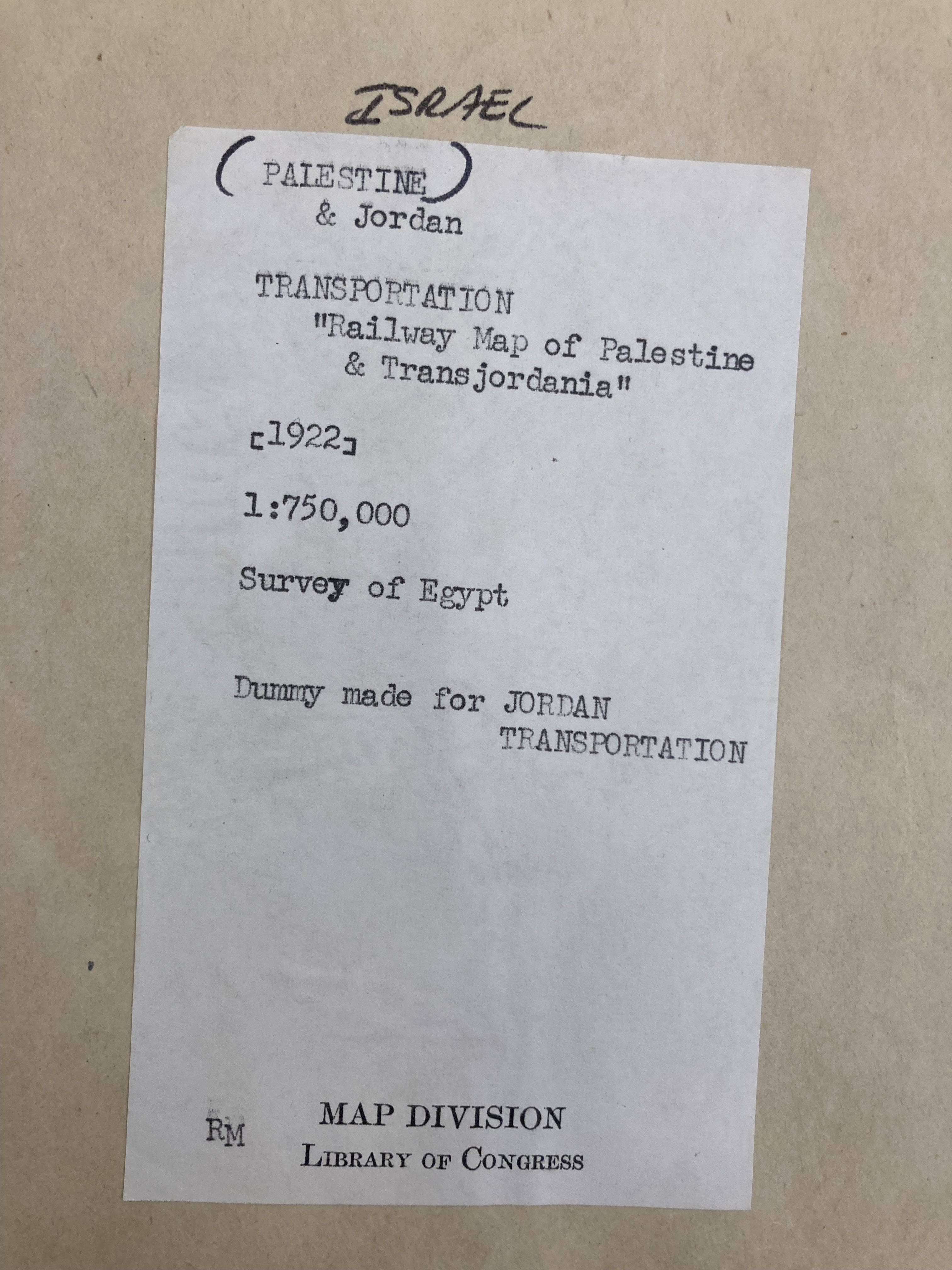

In many cases, these limits are not only to be found in the contents of the archive – in my case, maps – but, importantly, also in the physical edifice of the archive itself. For instance, all maps of Palestine before and after the creation of the Israeli state in 1948, some dating back centuries, are labelled “Israel” in the vast collection of the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. (a practice shared with the Royal Geographical Society archives in London). It is not uncommon to find a folder initially labelled “Palestine” crossed out and replaced with “Israel” (figure 3).

Figure 3 Library of Congress Archive Copyright Zena Agha

Such a brash overwrite acts as a synecdoche of the broader Zionist imperial project and its logic of elimination. As Patrick Wolf reminds us, the settler’s impulse is first to erase and eliminate the native, and second, to erect a new colonial society on the stolen land.[11] The archive facilitates the former, the state (and its allies) execute the latter.

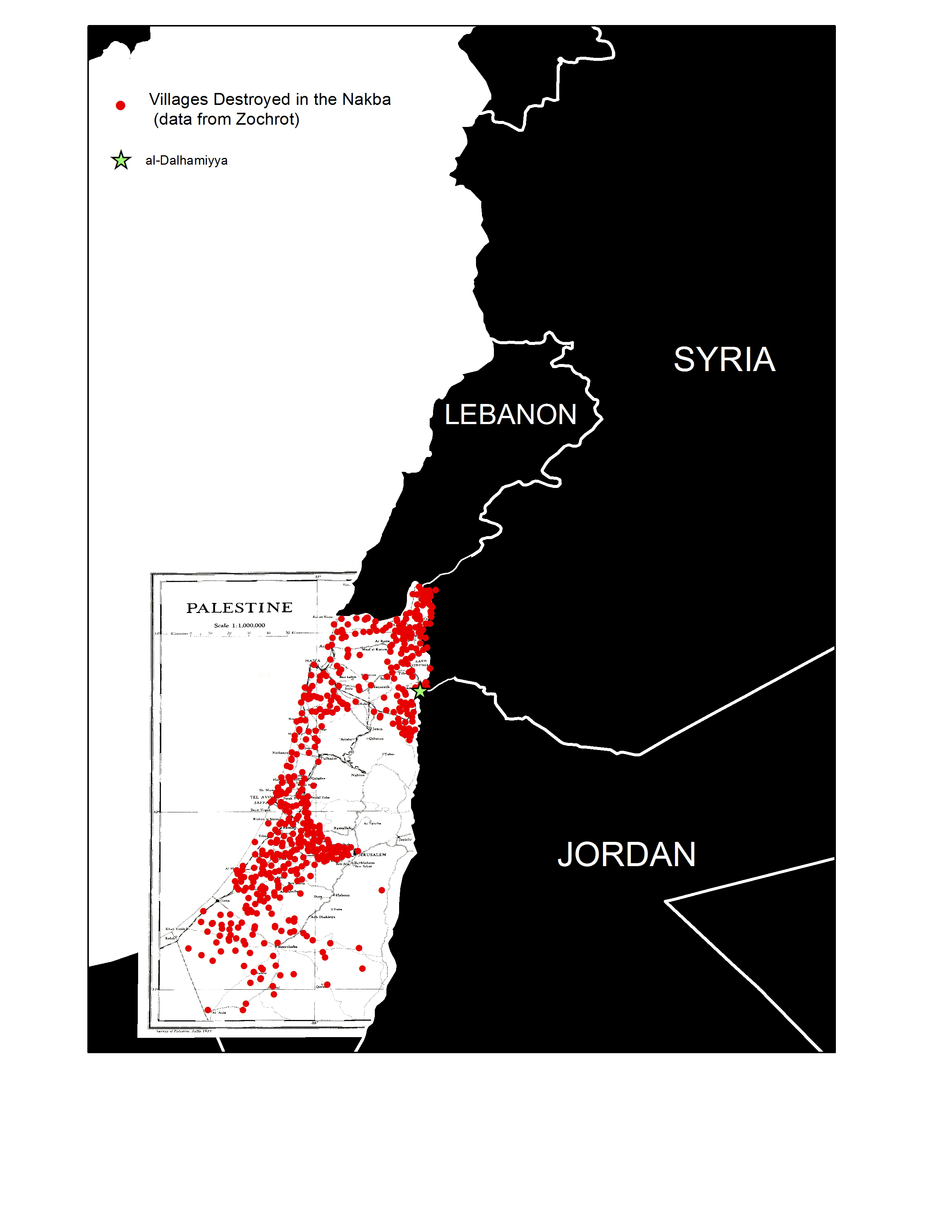

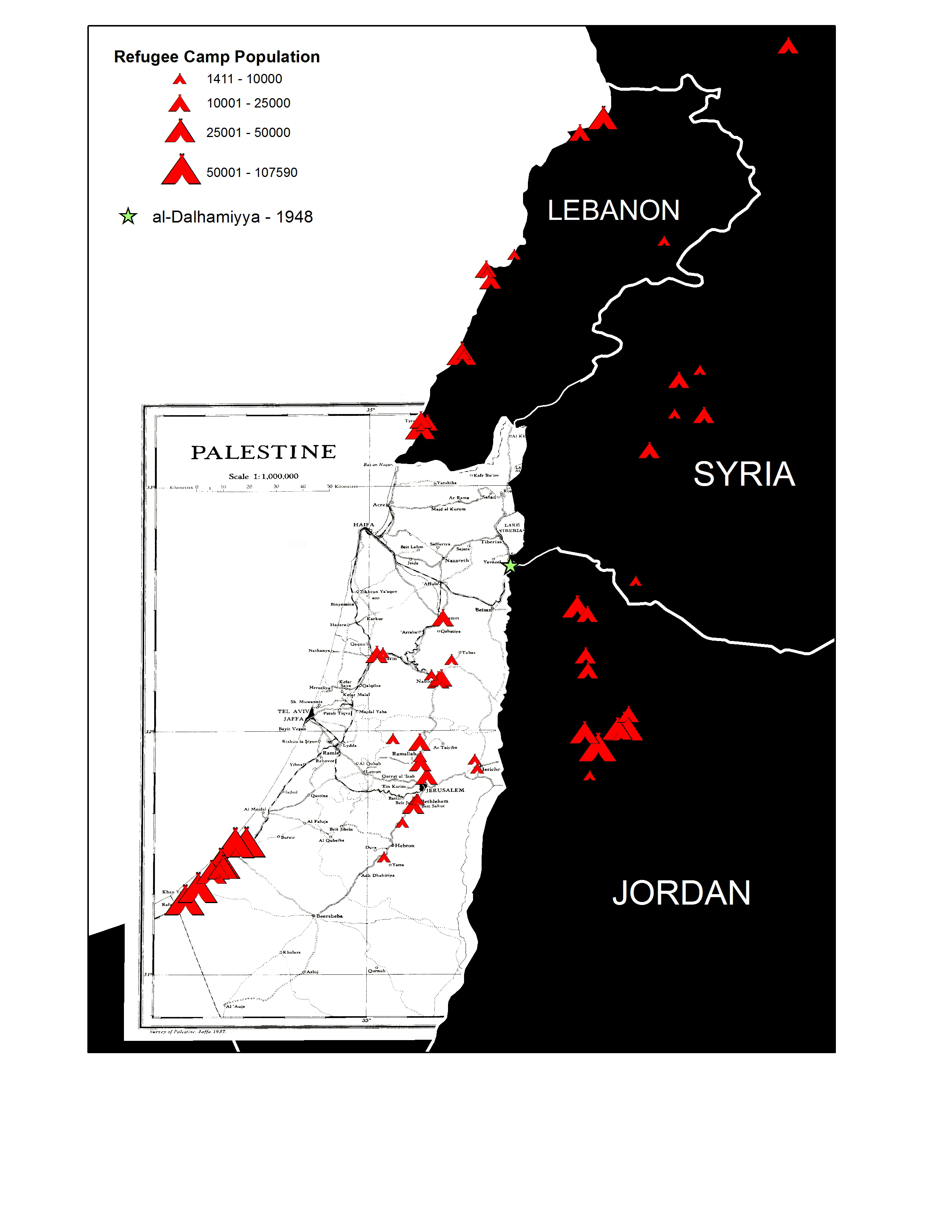

And yet, Palestinians insist on imagining and creating a reality beyond the present. Whether in Palestine or in exile, academics, mapmakers, organizers, and artists have learned to destabilize the archive to conceptualize alternative realities. In my own case, I have used technologies and practices including Photoshop, Risoprint (best described as digital screen printing), collage, embroidery and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software to reinscribe Palestine in cartographic terms. For instance, I geo-referenced a British colonial map from 1935 to depict villages destroyed in the Nakba (figure 4) and the location of Palestinian refugee camps across the region (figure 5).

Figure 4 Counter-Map of Destroyed Villages

Figure 5 Counter-Map of Refugee Camps Copyright Zena Agha

Since 1948, Palestinians have held onto the memory of destroyed homes and villages through the creation of atlases, maps, memoirs, visual art, books, oral histories, and websites. The right of return for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced people is not just a political solution but also the first step in a process of decolonization. Decolonizing maps involves acknowledging the experience of the colonial subjects (Palestinians) on the one hand, and documenting and exposing the colonial systems and structures (Zionist expansionism) on the other. It requires what David Harvey calls “the geographical imagination” – linking social imagination with a spatial-material consciousness.[12]

While there is valid criticism that counter-maps reproduce or embed existing exclusionary territorial and spatial practices, ongoing counter-mapping efforts demonstrate how Palestinians and their allies are creating a decolonizing cartography beyond simply (re)asserting lines on an existing map.[13] Rather, these efforts put personal and collective memories in spatial terms and incorporate them into a legal and political framework. This includes initiatives and projects such as Palestine Open Maps in 2018, the first open-source mapping project based around historical maps from the British Mandate period, as well as Decolonizing Art and Architecture Residency and Forensic Architecture. This is largely thanks to technological advances in GPS and GIS, which provide a foundation upon which to play, imagine and (re)build in spatial-cartographic terms.

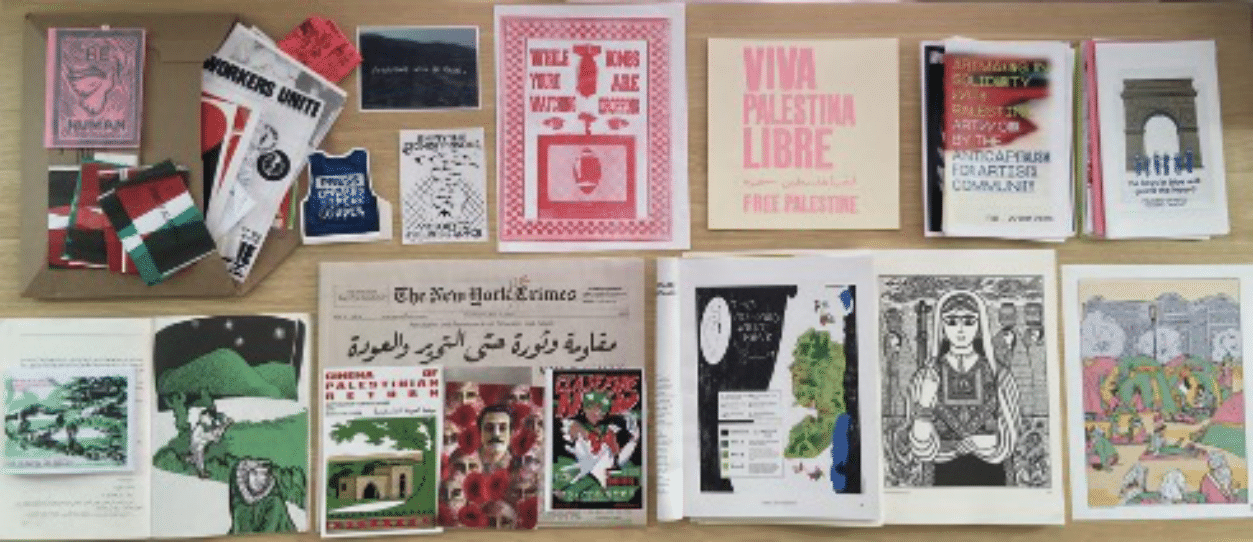

Moreover, the work of artists enables Palestinians to oppose and subvert the hegemonic discourse and assert an alternative vision of liberation and return. Examples include works by Mona Hatoum (“Present Tense” 1996, “Bukhara” 2007), Larissa Sansour (“Nation Estate” 2012, “In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain” 2015) and Amir Zuabi (“Cold Floors” 2021). The current onslaught has seen a wealth of incisive work from younger artists and architects who are creating despite intense repression; see for instance Mariam Tolba (“Map of Palestinian Displacement: Behind Every Infographic is a Million Stories” 2024), Omar El Amine (“The Shahada of the Olive Tree” 2024), Zain Al-Sharaf Wahbeh (“The Image as an Archive” 2024), Tessnim Tolba (“Saharan Winds” 2024) and Nadine Fattaleh (“Materials of Solidarity” 2024 – image 6).

Figure 6 Materials of Solidarity, Nadine Fattaleh

Crucially, these initiatives are often reinforced by, or juxtaposed with, Palestinian efforts to return to destroyed villages in reality. For instance, the internally displaced inhabitants of villages including Iqrit, Al-Walaja, and Al-Araqib returned decades after their initial expulsion despite the risk of state violence and demolition, in addition to more coordinated events such as the Great March of Return in Gaza from 2018, the Unity Uprising in May 2021 or Operation Al-Aqsa Flood in October 2023. These actions lend credence to Edward Said’s assertion that geography may be “the art of war but can also be the art of resistance if there is a counter-map and a counter-strategy.”[14]

My work both within and beyond the archive examines maps not solely as visual artifacts of a bygone era; rather it is part of a search for blueprints. Clues remain for what a decolonized and liberated future for Palestine and its people could look like – and what beauty there is to find along the way.

Read other articles in this boquet:

Paletine Open Maps by Ahmad Barclay and Majd Al-Shihabi

Settling Shadows: Cartographic Analysis of Settler Colonialism in the West Bank by Zaynab Nemr, Rami Zurayk, Jad Isaac, and Issa Zboun

[1]Puleng Segalo, Einat Manoff and Michelle Fine. ‘Working With Embroideries and Counter-Maps: Engaging Memory and Imagination Within Decolonizing Frameworks’. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3. (2015) 342-364. 10.5964/jspp.v3i1.145, 358

[2] Zena Agha, James Esson, Mark Griffiths. & Mikko Joronen. Gaza: A decolonial geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 49 (2024), e12675.

[3] Walid, Khalidi, ed. All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992.)

[4] Noga Kadman, Erased from space and consciousness: Israel and the depopulated Palestinian villages of 1948, (Indinian; Indiana University Press, 2015)1.

[5] J.B Harley, The new nature of maps: essays in the history of cartography (Johns Hopkins press, 2002) 36.

[6] Harley, The new nature of maps: essays in the history of cartography, 150-1.

[7] Harley, The new nature of maps: essays in the history of cartography, 35.

[8] Jacques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression’, Diacritics, 25 (1995), 9-63, 11.

[9] Beshara Doumani, “Archiving Palestine and Palestinians: The Patrimony of Ishan Nimr,” Jerusalem Quarterly (2009), 36.

[10] Saidiya V. Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019), xv.

[11] Patrick Wolfe, "Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native," Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006/12/01 2006): 388,https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

[12] David Harvey, The 'New' Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession,” Socialist Register, 40 (2004), 63-87.

[13] Jess Bier, Jess Bier, Mapping Palestine, Mapping Israel, (MIT Press, 2017), 68.

[14] Edward W Said, Peace and its discontents: Essays on Palestine in the Middle East peace process (Vintage, 2012), 27.

Special thanks to Scott Walker from the Harvard Map Collection for his assistance with the GIS counter-maps.