[This article is part of a bouquet developed by the Jadaliyya Environment and Palestine Page editors to highlight the work of critical mapping initiatives and research on the role of mapping spaces in Palestine, Lebanon, and across the region. The authors highlight not only their own work and its methodologies, but also discuss how they hope it contributes to our larger understanding of space and popular conversations of the spaces we inhabit and study. Read the rest of the articles featured in this bouquet linked at the bottom.]

Tell us about your project. What time(s), place(s), and topic(s) does your work/project cover?

Palestine Open Maps (POM) is a platform that allows users to explore, search and download historical maps and spatial data on Palestine in English and Arabic. The platform includes historical maps with layers that piece together hundreds of detailed British maps of Palestine from the 1870s up to the mid-1940s. Most importantly, this allows users to see hundreds of towns and villages immediately before the Nakba, and to view this side-by-side with present day mapping and aerial photography.

How did you come to develop your project? What sources and/or analytics did you draw upon?

The initial idea for POM was inspired by our discovery that hundreds of 1:20,000 scale British Mandate era maps of Palestine had been digitised and made available through an online document viewer by the Israeli National Library. The maps within the viewer could not be downloaded at a high resolution, and were not connected to the spatial data that would allow people to search for specific locations or navigate between the individual map sheets in a meaningful way. However, we immediately saw the potential to scrape the maps at a high resolution, stitch them together and open source them to the public.

Having scraped the maps, our opportunity to realize the project came about through Impact Data Lab, a data hackathon event co-curated by Visualizing Palestine and Studio-X Amman in early 2018. Over four days, we were able to georeference the maps and cross-reference population data for over a thousand localities from sources, including Palestine Remembered and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, to build an initial proof-of-concept map viewer.

The development of the initial POM website was supported by Visualizing Palestine and launched roughly two months later on Nakba Day 2018. We have continued to develop the site largely as a hobby project since that time, adding features including map sheet downloads, split-screen view, vector map overlays, links to other platforms, and an experimental 3D mode.

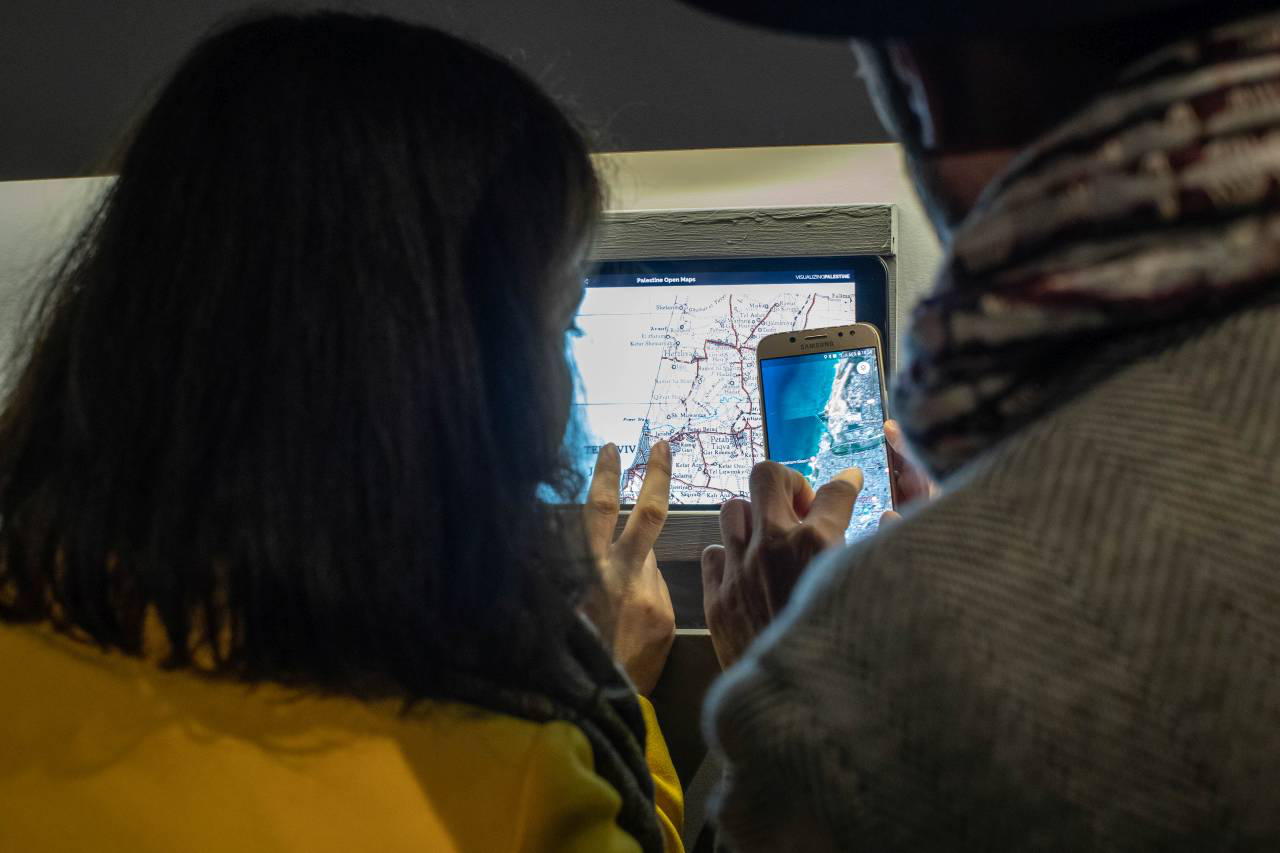

Visitors using Palestine Open Maps to locate Jaffa/Tel Aviv area at “A National Monument” exhibit in Beirut in 2019. Credit: Joe Hany Kairouz.

What is your aim for the project? For example, who do you hope to reach? How do you hope people will engage with the work?

Aside from a historical archive, we view POM as a critical component of a larger project of reimagining the space and politics of the region through a geographic lens. The genocide in Gaza has reminded us of the urgency of building a political future for Palestine, beyond genocide and apartheid. We believe that identifying such a political future requires deep study of the history of the region, and thoughtful engagement with archival materials that tell that history.

Through an open approach that models custodianship principles, we actively encourage other projects to utilize the maps and data that POM has helped to open source. Numerous people have told us that they are independently using POM and its maps and data, and are able to do so because of our open approach to managing the project.

If you visit the Wikipedia pages of the depopulated villages of Palestine, you will find that most of them include excerpts of maps downloaded from POM. POM’s approach to historical maps has inspired projects such as the Palestinian Museum’s Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question as a way to visualize their database of places in Palestine, and have been used as a source for investigations and reports by Forensic Architecture and the Financial Times.

Individuals such as Tarek Bakri rely on POM as one of their essential tools for their investigations to find the homes of Palestinian refugees returning to visit their villages of their grandparents. In fact, the usage data for the website suggests that it is more used in historic Palestine — and particularly within the territory occupied since 1948 — than in any other country.

We ourselves have also made use of POM maps and data in a range of other projects. For example, Ahmad used POM map layers as a base for the Palestinian Oral History Map developed with the American University of Beirut. He also utilized the maps as a basis for the A National Monument exhibit in collaboration with Marwan Rechmaoui at Dar El Nimr in Beirut, and the One Map, Multiple Mediums follow up exhibit at Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai.

We hope that, by elevating the visibility and utility of these maps, we have been able to contribute in a small way to transforming narratives of the past, present and future of Palestine.

Using Palestine Open Maps to orient oneself while on a hike in northern historic Palestine. Credit: anonymous.

How do you see this work, or mapping in general, contributing to academic and/or popular conversations on Palestine?

The driving principle of POM has always been to open source the maps and data that it contains, and to provide a rich resource for present and future generations of Palestinians, contextualizing the geographic knowledge in time and narrative. Further, beyond being a repository of map data, to us POM also represents an infrastructure for a wider community of people engaged with the question of Palestine through land, memory, and future imaginaries. We run events called “mapathons,” where people help us to extract data from the historical maps using easy to learn GIS tools based on the open source OpenStreetMap infrastructure.

We have conducted mapathons in places such as Baddawi Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, Birzeit University in Palestine, Milano Design Week in Italy, and even the British Library in the UK. In each of these mapathons, participants contribute to our public dataset of historical geographic information, and contribute to the reappropriation of the maps from their colonial origins, transforming them into a collectively owned, continuously expanding and evolving digital resource.

Each mapathon is an engagement with a new section of the community, with a wide variety of different motivations to contribute to the project. Whereas in the camps in Lebanon, we were typically greeted by young Palestinian refugees interested to find and explore their own towns and villages in Palestine, in other communities we found people with a general interest in historical maps and digital mapping technologies, and many others simply trying to find their own small, meaningful way to contribute to the Palestinian struggle for liberation and return.

Read other articles in this bouquet:

Counter-Mapping the Archive by Zena Agha

Settling Shadows: Cartographic Analysis of Settler Colonialism in the West Bank by Zaynab Nemr, Rami Zurayk, Jad Isaac, and Issa Zboun